Alopias palatasi

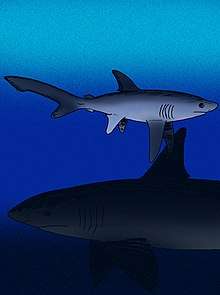

Alopias palatasi ("Palatas' fox"), commonly referred to as the serrated giant thresher, is an extinct species of giant thresher shark that lived approximately 20.44 to 13.7 million years ago during the Miocene epoch, and is known for its uniquely serrated teeth. It is only known from such isolated teeth, which are large and can measure up to an excess of 4 centimetres (2 in), equating to a size rivaling the great white shark, but are rare and found in deposits in the East Coast of the United States and Malta. Teeth of A. palatasi are strikingly similar to those of the giant thresher Alopias grandis, and the former has been considered as a variant of the latter in the past. Scientists hypothesized that A. palatasi may have had attained lengths comparable with the great white shark and a body outline similar to it.

| Alopias palatasi | |

|---|---|

.png) | |

| Tooth from Beaufort, South Carolina | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Order: | Lamniformes |

| Family: | Alopiidae |

| Genus: | Alopias |

| Species: | †A. palatasi |

| Binomial name | |

| †Alopias palatasi Kent & Ward, 2018 | |

Discovery and taxonomy

In 2002, rumors began about discoveries of a new type of large serrated shark teeth pertaining to an undescribed species of mackerel shark from Miocene deposits in South Carolina by amateur collectors and fossil dealers. While these fossils were often dismissed as teeth from other sharks such as the megalodon and the false-toothed mako (Parotodus benedenii), a consensus was reached that they were likely from a morphotype of the giant thresher Alopias grandis. Despite the large attention given by amateur collectors and fossil dealers, such fossils remained unmentioned in the scientific literature for many years.[3]

In 2014, a fossil dealer named Mark Palatas donated a single tooth to paleoichthyologist David Ward in hopes that it would spark a formal description. Ward subsequently initiated its research with his colleague Bretton Kent.[3] The following year in October 2015, Ward and Kent presented a poster to the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology reporting the existence of the new species.[3] In 2018, the two published a formal paper giving it the scientific name Alopias palatasi in honor of Palatas, and as a sister species of A. grandis.[1]

The two designed seven type specimens from the collections of the Calvert Marine Museum (CMM) and the National Museum of Natural History (USNM). The holotype is CMM-V-385, a right upper anterior tooth found in Bed 12 of the Calvert Formation cliffs near Parkers Creek. Six paratypes were also designated: CMM-V-3876, a heavily worn tooth found at the beaches at the Flag Ponds Nature Park that was reworked from either the Choptank Formation or the Plum Point Member of the Calvert Formation; CMM-V-3981, a right upper lateral tooth collected from the beaches near Parkers Creek; CMM-V-4242, a tooth from the beaches of Calvert County, Maryland; CMM-V-5823, a left lower lateral tooth and the tooth that Palatas donated, which he found in the downstream of the May River, South Carolina; USNM 411148, a tooth also found in Bed 12 of the Calvert Formation cliffs near Parkers Creek; and USNM 639783, a tooth also collected from the beaches near Parkers Creek.[1]

Description

A. palatasi is only known from isolated teeth. They are large, measuring up to an excess of 4 centimetres (2 in) in height and suggesting a shark that grew to similar sizes or was larger than the modern great white shark,[3] which grows between 3.3–4.8 metres (11–16 ft) on average[4] and up to 6.6 metres (22 ft) in maximum length.[5] The crown is arched and broad with cutting edges possessing coarse serrations that are largely irregular in size but become finer towards the tip. The root consists of deep root lobes and a strongly arched base. The A. palatasi dental structure is heterodontic, meaning that the shape of teeth differs between each tooth in a jaw. A. palatasi teeth are most similar in size and form to the teeth of its sister species A. grandis, the only main difference being the presence of serrations in the former.[1] The size, broadness, and serrations of A. palatasi teeth are also convergently similar to the modern great white shark. The dental similarities between the two led Ward and Kent to hypothesize that A. palatasi may not have possessed the elongated tail seen in modern thresher sharks and instead may have had a body outline similar to the great white shark.[3]

Paleoecology

The majority of A. palatasi fossils are known from Burdigalian to Serravallian deposits of the Calvert Formation in Maryland and Virginia, the Pungo River Formation in North Carolina, and the Coosawhatchie Formation in South Carolina. A. palatasi is also occasionally known from the Upper Globigerina Limestone in Malta, which suggests that its distribution was not restricted to the western Atlantic, but extended into the Mediterranean. However, A. palatasi fossils have not been found elsewhere in the Old World, though teeth of A. grandis have been found in Belgium.[1]

The United States East Coast localities have yielded a diverse and rich assemblage of marine vertebrates. The Calvert Formation holds twelve genera of cetaceans such as the proto-dolphins Squalodon, Kentriodon, and Eurhinodelphis, the physeteroid Orycterocetus, the mysticetes Mesocetus[6] and Eobalaenoptera,[7] and unspecified beaked whales.[8] Other marine mammals include pinnipeds such as the earless seal Leptophoca.[9] Of the sharks, fourteen genera are known from the Calvert Formation. These include various species of makos, Carcharhinus sharks, tiger sharks, thresher sharks, the giant snaggletooth Hemipristis serra, the early great white Cosmopolitodus hastalis, Parotodus benedenii, Notorynchus, and the otodontids megalodon[10] and its direct ancestor Carcharocles chubutensis. The Pungo River and Coosawhatchie Formations hold similar assemblages of marine vertebrates. It is notable that A. palatasi fossils have been typically found comingled with C. chubutensis.[1]

References

- Bretton W. Kent; David J. Ward (2018). "A new species of giant thresher shark (Family Alopiidae) with serrated teeth". Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology. 100 (1): 157–160.

- Kenneth G. Miller; Peter J. Sugarman (1995). "Correlating Miocene sequences in onshore New Jersey boreholes (ODP Leg 150X) with global δ18O and Maryland outcrops". Geology. 23 (8): 747–750. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1995)023<0747:CMSION>2.3.CO;2. S2CID 1514786.

- David J. Ward; Bretton Kent (2015), A new giant species of thresher shark from the Miocene of the United States, Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.1723.0969

- Mary Parrish. "How Big are Great White Sharks?". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History Ocean Portal. Archived from the original on 2019-06-12. Retrieved 2019-11-17.

- Alessandro De Maddalena; Marco Zuffa; Lovrenc Lipej; Antonio Celona (2001). "An analysis of the photographic evidences of the largest great white sharks, Carcharodon carcharias (Linnaeus, 1758), captured in the Mediterranean Sea with considerations about the maximum size of the species" (PDF). Annales des Sciences Naturelles. 2 (25): 193–206.

- Michael D. Gottfried; David J. Bohaska; Frank C. Whitmore Jr. (1990). "Miocene Cetaceans of the Chesapeake Group". Proceedings of the San Diego Society of Natural History. 29 (1994): 229–238.

- Alton C. Dooley Jr.; Nicholas C. Fraiser; Zhe-Xi Luo (2001). "The earliest known member of the rorqual—gray whale clade (Mammalia, Cetacea)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (2): 453–463. doi:10.1671/2401.

- Olivier Lambert; Stephen J. Godfrey; Anna J. Fuller (2010). "A Miocene Ziphiid (Cetacea: Odontoceti) from Calvert Cliffs, Maryland, U.S.A.". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (5): 1645–1651. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.501642.

- Annalisa Berta; Morgan Churchill; Robert W. Boessenecker (2018). "The Origin and Evolutionary Biology of Pinnipeds: Seals, Sea Lions, and Walruses". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 46 (1): 203–228. Bibcode:2018AREPS..46..203B. doi:10.1146/annurev-earth-082517-010009.

- Christy C. Visaggi; Stephen J. Godfrey (2010). "Variation in composition and abundance of Miocene shark teeth from Calvert Cliffs, Maryland". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (1): 26–35. doi:10.1080/02724630903409063.