Stanford White

Stanford White (November 9, 1853 – June 25, 1906) was an American architect. He was also a partner in the architectural firm McKim, Mead & White, the frontrunner among Beaux-Arts firms. He designed many houses for the rich as well as numerous civic, institutional, and religious buildings. His design principles embodied the "American Renaissance".

Stanford White | |

|---|---|

Photograph of White by George Cox, ca. 1892 | |

| Born | November 9, 1853 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | June 25, 1906 (aged 52) New York City, U.S. |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Spouse(s) | Bessie Springs Smith

( m. 1884; |

| Children | Lawrence Grant White |

| Parent(s) | Alexina Black Mease Richard Grant White |

| Buildings | Rosecliff, Newport, RI Madison Square Garden II, NYC Washington Square Arch, NYC New York Herald Building, NYC Savoyard Centre, Detroit Lovely Lane Methodist Church, Baltimore Rhode Island State House, Providence University of Virginia Rotunda The Nottingham on 30th Street |

.jpg)

In 1906, White was shot and killed by the mentally unstable millionaire Harry Kendall Thaw, who had become obsessed about White's previous relationship with Thaw's wife, actress Evelyn Nesbit.[1] This led to a court case which was dubbed "The Trial of the Century" by contemporary reporters.[2][3]

Early life and training

White was born in New York City, the son of Shakespearean scholar Richard Grant White and Alexina Black Mease (1830–1921). His father was a dandy and Anglophile with no money, but a great many connections in New York's art world, including painter John LaFarge, Louis Comfort Tiffany, and Frederick Law Olmsted.[4]

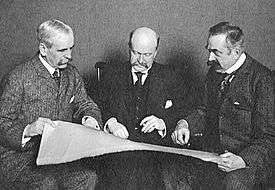

White had no formal architectural training; he began his career at the age of 18 as the principal assistant to Henry Hobson Richardson, the greatest American architect of the day and creator of a style recognized today as "Richardsonian Romanesque". He remained with Richardson for six years.[4] In 1878, White embarked for a year and a half tour of Europe, and when he returned to New York in September 1879, he joined Charles Follen McKim and William Rutherford Mead to form McKim, Mead and White. As part of the partnership, all commissions designed by the architects were identified as being the work of the collective firm, not any individual architect.[4]

In 1884, White married 22-year-old Bessie Springs Smith. She hailed from a socially prominent Long Island family; her ancestors were early settlers of the area, and Smithtown, New York, was named for them. The couple's estate, Box Hill, was both a home and a showplace for the luxe design aesthetic White offered to prospective wealthy clients. A son, Lawrence Grant White, was born in 1887.[5]

McKim, Mead and White

Commercial and civic projects

In 1889, White designed the triumphal arch at Washington Square, which, according to White's great-grandson, architect Samuel G. White, is the structure White should be best remembered for. White was the director of the Washington Centennial celebration and created a temporary triumphal arch which was so popular, money was raised to construct a permanent version.[4]

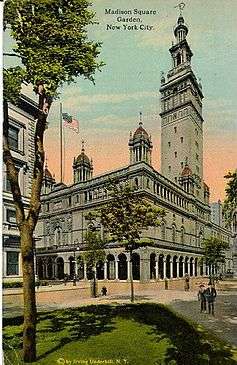

Elsewhere in New York City, White designed the Villard Houses (1884), the second Madison Square Garden (1890; demolished in 1925),[6] the Cable Building – the cable car power station at 611 Broadway – (1893),[7] the baldechin (1888 to mid-1890s)[8] and altars of Blessed Virgin[9] and St. Joseph[10] (both completed in 1905) at St. Paul the Apostle Church; the New York Herald Building (1894; demolished); the IRT Powerhouse on 11th Avenue and 58th Street; the First Bowery Savings Bank, at the intersection of the Bowery and Grand Street (1894); Judson Memorial Church on Washington Square; the Century Club; and Madison Square Presbyterian Church, as well as the Gould Memorial Library (1903), originally for New York University, now on the campus of Bronx Community College and the location of the Hall of Fame for Great Americans.

Outside of New York City, White designed:

- The First Methodist Episcopal Church in Baltimore, Maryland (1887), now Lovely Lane United Methodist Church.

- The Cosmopolitan Building, a three-story Neo-classical Revival building topped by three small domes, built in Irvington, New York, in 1895 as the headquarters of Cosmopolitan Magazine.

- Cocke, Rouss, and Old Cabell halls at the University of Virginia. In 1989, he rebuilt the university's Rotunda, three years after it had burned down. (In 1976, his re-creation was reverted to Thomas Jefferson's original design for the United States Bicentennial.)

- The Blair Mansion at 7711 Eastern Ave. in Silver Spring, Maryland (1880), now being used as a violin store.[11]

- The Boston Public Library and the Boston Hotel Buckminster, both still standing.

- The 1902 Benjamin Walworth Arnold House and Carriage House in Albany, New York.

He helped to develop Nikola Tesla's Wardenclyffe Tower, his last design.

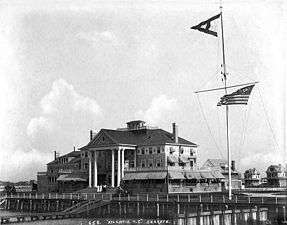

White designed several clubhouses that became focal points of New York society, and which still stand: the Century, Colony, Harmonie, Lambs, Metropolitan, and Players clubs. His Shinnecock Hills Golf Clubhouse design is said to be the oldest golf clubhouse in America and is now a golf landmark. However, his clubhouse for the Atlantic Yacht Club, built in 1894 overlooking Gravesend Bay, burned down in 1934. Sons of society families also resided in White's St. Anthony Hall Chapter House at Williams College, now occupied by college offices.[12]

Residential properties

In the division of projects within the firm, the sociable and gregarious White landed the most commissions for private houses.[13] His fluent draftsmanship was highly convincing to clients who might not get much visceral understanding from a floorplan, and his intuition and facility caught the mood. White's Long Island houses have survived well, despite the loss of Harbor Hill in 1947, originally set on 688 acres (2.78 km2) in Roslyn. White's Long Island houses are of three types, depending on their locations: Gold Coast chateaux; neo-Colonial structures, especially those in the neighborhood of his own house at "Box Hill" in Smithtown, New York (White's wife was a Smith); and the South Fork houses from Southampton to Montauk Point. He also designed the Kate Annette Wetherill Estate in 1895.

White designed a number of other New York mansions as well, including the Iselin family estate "All View" and "Four Chimneys" in New Rochelle. White designed several country estate homes in Greenwich, Connecticut, including the Seaman-Brush House (1900), now the Stanton House Inn, a bed and breakfast.[14] In New York's Hudson Valley, he designed the 1896 Mills Mansion in Staatsburg. Among his "cottages" in Newport, Rhode Island, at Rosecliff (for Mrs. Hermann Oelrichs, 1898–1902) he adapted Mansart's Grand Trianon, but provided this house built for receptions, dinners, and dances with fluent spatial planning and well-contrived dramatic internal views en filade. His "informal" shingled cottages usually featured double corridors for separate circulation, so that a guest never bumped into a laundress with a basket of bed linens. Bedrooms were characteristically separated from hallways by a dressing-room foyer lined with closets, so that an inner door and an outer door give superb privacy.

One the few surviving urban residences designed by White is the Ross R. Winans Mansion in Baltimore's Mount Vernon-Belvedere neighborhood, now the headquarters for Agora, Inc. Built for Ross R. Winans, heir to Ross Winans, in 1882 the mansion is a premier example of French Renaissance revival architecture. Since Winans' residence, it served as a girls preparatory school, doctor's offices, and a funeral parlor before being acquired by Agora Publishing. In 2005, Agora completed an award-winning renovation project.[15]

White lived the same life as his clients, albeit not quite so lavishly, and he knew how the house had to perform: like a first-rate hotel, theater foyer, or a theater set with appropriate historical references. He was an apt designer, who was ready to do a cover for Scribner's Magazine or design a pedestal for his friend Augustus Saint-Gaudens' sculpture. He extended the limits of architectural services to include interior decoration, dealing in art and antiques, and even planning and designing parties. He collected paintings, pottery, and tapestries, and if White could not procure the right antiques for his interiors, he would sketch neo-Georgian standing electroliers or a Renaissance library table. His design for elaborate picture framing, the Stanford White frame, still bears his name today. Outgoing and social, he possessed a large circle of friends and acquaintances, many of whom became clients. White had a major influence in the "Shingle Style" of the 1880s, on Neo-Colonial style, and the Newport cottages for which he is celebrated.

He designed and decorated Fifth Avenue mansions for the Astors, the Vanderbilts (in 1905), and other high society families.

Personal life

White, a tall, flamboyant[4] man with red hair and a red mustache, impressed others as witty, kind, and generous. The newspapers frequently described him as "masterful", "intense", "burly yet boyish".[16] He was a sophisticated collector of all things rare and costly, such as artwork and antiquities. He maintained a multi-story apartment with a rear entrance on 24th street in Manhattan. One green-hued room was outfitted with a red velvet swing, which hung from the ceiling suspended by ivy-twined ropes. There are conflicting accounts of whether this swing was in the "Giralda" tower at the old Madison Square Garden, or in the nearby building at 22 West 24th Street, but sources seem to concur that the swing was a feature of the 24th Street location.[17]

The evidence of letters, including those of Augustus Saint-Gaudens to White, have encouraged recent biographers to conclude that White was, bisexual, and that the office of McKim, Mead & White were unruffled by this.[18] With respect to White's sexuality, his granddaughter has written that Stanford's eldest son (her father) was "unflinching in his awareness of Stanford's nature".[19]

Murder

White's presence at the roof garden theatre of Madison Square Garden on the night of June 25, 1906, had been an impromptu decision. White had originally planned to be in Philadelphia on business; he postponed the trip when his son, Lawrence, made an unexpected visit to New York. Accompanied by New York society figure James Clinch Smith,[20] they dined at Martin's, near the theatre, where Harry Kendall Thaw and his wife Evelyn Nesbit also dined. Thaw apparently saw White there.[21]

That evening's theatrical presentation was the premiere performance of Mam'zelle Champagne. During the show's finale, "I Could Love A Million Girls", Thaw approached White, produced a pistol, standing some two feet from his target, said, "You've ruined my wife",[21] and fired three shots at White, hitting him twice in the face and once in his upper left shoulder, killing him instantly. Part of White's face was torn away, and the rest of his features were unrecognizable, blackened by gunpowder.[1][22] The crowd's initial reaction was one of good cheer, as elaborate party tricks among the upper echelon of New York society were common at the time. However, when it became apparent that White was dead, hysteria ensued.

Thaw, a Pittsburgh millionaire with a history of severe mental instability, was a jealous husband who saw White as his rival. White had first inebriated and then raped an unconscious Nesbit when she was 16 and White was 47 years old. In the five years following, White had remained a potent presence in Nesbit's life.[23] However, by the time of the murder, White had moved on to other lovers,[21] and it is conjectured that White was unaware of Thaw's deep-seated grievance against him. White considered Thaw a poseur of little consequence, categorized him as a clown, and most tellingly, called him the "Pennsylvania pug" – a reference to Thaw's baby-faced features.[24] In reality, Thaw both admired and resented White's social stature. More significantly, he recognized that he and White shared a passion for similar lifestyles. However, unlike Thaw, who had to operate in the shadows, White could carry on without censure, and seemingly, with impunity.[25]

Nineteen-year-old Lawrence Grant White was guilt ridden after his father was slain, blaming himself for his death. "If only he had gone [to Philadelphia]!" he lamented.[26] Years later, he would write bitterly, "On the night of June 25th, 1906, while attending a performance at Madison Square Garden, Stanford White was shot from behind [by] a crazed profligate whose great wealth was used to besmirch his victim's memory during the series of notorious trials that ensued."

White was buried in St. James, New York.[27]

News coverage

The morning following the murder, there was blanket press coverage, as well as editorial speculation and gossip, and journalistic interest in the story was sustained. William Randolph Hearst's newspapers played up the story and the murder trial became known as "The Trial of the Century". The voracious press interest was used by both the defense and prosecution in Thaw's murder trial to feed malleable reporters any "scoops" that would give their respective sides an advantage in the public forum.[28]

Details, no matter how peripheral to White's murder, were seized on by reporters. Facts were thin, and sensationalist reportage was plentiful in this, the heyday of tabloid journalism. The hard-boiled male crime reporters were bolstered by a contingent of female counterparts, christened "Sob Sisters", also known as the "Pity Patrol".[29] Their stock in trade was the human-interest piece, heavy on sentimental tropes and melodrama, crafted to pull on the emotions and punch them up to fever pitch.

In death White was subject to a frenzy of printed invective, which excoriated his character and his professional achievements as an architect. The Evening Standard concluded he was "more of an artist than architect", and said his work spoke of his "social dissolution". The Nation was also critical: "He adorned many an American mansion with irrelevant plunder." The yellow press used lurid language to demonize White as "a sybarite of debauchery, a man who abandoned lofty enterprises for vicious revels."[30]

Defenses

Few friends or associates came forward to publicly defend White. His close friend, sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, was gravely ill and unable to speak out.

Richard Harding Davis, a war correspondent and reputedly the model for the "Gibson Man", was angered by the tabloid press, which, he was adamant, had distorted the facts. An editorial, which appeared in Vanity Fair, lambasting White and shredding his reputation, prompted Davis to pen a rebuttal. The article appeared on August 8, 1906, in Collier's magazine:

Since his death White has been described as a satyr. To answer this by saying that he was a great architect is not to answer at all...what is more important is that he was a most kindhearted, most considerate, gentle and manly man, who could no more have done the things attributed to him than he could have roasted a baby on a spit. Big in mind and in body, he was incapable of little meanness. He admired a beautiful woman as he admired every other beautiful thing God has given us; and his delight over one was as keen, as boyish, as grateful over any others.[31]

Autopsy

The autopsy report made public by the coroner's testimony at the Thaw trial revealed that White was seriously unwell at the time of his murder. In fact, he would have succumbed shortly to any of the various illnesses he suffered from: Bright's disease, incipient tuberculosis, and severe liver deterioration.[32]

In popular culture

- The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing – a 1955 movie in which Ray Milland played White[33]

- The 1975 historical fiction novel Ragtime by E. L. Doctorow

- The 1981 film Ragtime, based on the novel, in which White was played by Norman Mailer, Thaw by Robert Joy, and Nesbit by Elizabeth McGovern[34]

- The 1996 musical Ragtime, based on the novel[35]

- "Dementia Americana" – a long narrative poem by Keith Maillard (1994, ISBN 9780921870289)

- My Sweetheart's the Man in the Moon – a play by Don Nigro (ISBN 9780573642388)[36]

- La fille coupée en deux ("The Girl Cut in Two") – a 2007 film by Claude Chabrol which was inspired, in part, by the Stanford White scandal.[37]

Gallery

900 Broadway on the corner of East 20th Street, in the Flatiron District of Manhattan, New York City.

900 Broadway on the corner of East 20th Street, in the Flatiron District of Manhattan, New York City.

White renovated the mansion at #16 Gramercy Park for actor Edwin Booth to be the headquarters for the Players Club.

White renovated the mansion at #16 Gramercy Park for actor Edwin Booth to be the headquarters for the Players Club.

The second incarnation of Madison Square Garden was designed by White

The second incarnation of Madison Square Garden was designed by White

Interior of Lovely Lane Methodist Church in Baltimore, Maryland

Interior of Lovely Lane Methodist Church in Baltimore, Maryland The Cosmopolitan Building c.1900 (from an ad in Cosmopolitan Magazine)

The Cosmopolitan Building c.1900 (from an ad in Cosmopolitan Magazine) President Theodore Roosevelt seated in a chair designed by White for the State Dining Room of the White House, 1903.

President Theodore Roosevelt seated in a chair designed by White for the State Dining Room of the White House, 1903.

See also

- McKim, Mead and White

- Frederick Manson White, an architect, supposedly Stanford White's nephew

- Harry Kendall Thaw

References

Primary sources

White's extensive professional correspondence and a small body of personal correspondence, photographs, and architectural drawings by White are held by the Department of Drawings & Archives of Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library at Columbia University. His letters to his family have been edited by Claire Nicolas White, Stanford White: Letters to His Family 1997. The major archive for his firm, McKim, Mead & White, is held by the New-York Historical Society.

Notes

- "Benjamin Thaw Too Ill to be Told of His Brother's Crime". New York Times. June 26, 1906. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

Social and financial circles in Pittsburg were greatly shocked to-night by the news from New York that Harry K. Thaw had shot and killed Stanford White. The Thaws have for years been social leaders here. Harry Kendall Thaw, the husband of Florence Evelyn Nesbit, over whom Thaw and White are said to have quarreled, has for some years been the black sheep of the Thaw family.

- Roberts, Sam (August 23, 2018). "There's Plenty to Read About the 'Trial of the Century'". The New York Times.

- Blecher, George (August 3, 2018). "Murder, Politics and Architecture: The Making of Madison Square Park". The New York Times.

- Lockhart, Mary. Treasures of New York: Stanford White (TV, 2014) WLIW. Broadcast accessed:2014-01-05

- Harrison, Helen A. (November 28, 2004). "Creative Lines, Haunted by Scandal". The New York Times.

- "Madison Square Garden" on the New York Architecture website

- Gray, Christopher. "Streetscapes: The 1893 Cable Building, Broadway and Houston Street; Built for New Technology by McKim, Mead & White" New York Times (November 7, 1999)

- "Photos and videos by Paulist Fathers (@PaulistFathers)". Pinterest. Retrieved 2017-04-20.

- "Church of St. Paul the Apostle, NYC". Pinterest. Retrieved 2017-04-20.

- "Church of St. Paul the Apostle, NYC". Pinterest. Retrieved 2017-04-20.

- Stoelker, Tom (October 6, 2011) "Murder, Love, and Insanity: Stanford White" The Architect's Newspaper

- "photograph". Archived from the original on December 1, 2007. Retrieved 2007-02-14.

- Roth, L. M. The architecture of McKim, Mead & White, 1870–1920: a building list 1978 provides a working list of commissions.

- "Seaman Brush House, 76 Maple Avenue, 1936" Greenwich Historical Society website

- "Baltimore Heritage - Ross Winans Mansion". Retrieved 2019-03-16.

- Uruburu, pp. 114-115.

- Dworin, Caroline H. (2007-11-04). "The Girl, the Swing and a Row House in Ruins". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-19.

- Broderick, Mosette (2010) Triumvirate: McKim, Mead & White Art, Architecture, Scandal, and Class in America's Gilded Age. New York: Knopf, pp. vii-viii, 41. ISBN 9780394536620

- Lessard, Suzannah (1996) The Architect of Desire: Beauty and Danger in the Stanford White Family. New York: Dell p. 204. ISBN 0385319428

- Lord, Walter. "Chapter 2". A Night to Remember. p. 5.

- Nevius, Michelle & Nevius, James (2009), Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City, New York: Free Press, ISBN 141658997X, pp.195-197

- Uruburu, pp.279, 282

- "Stanford White & Evelyn Nesbit" People (February 12, 1996)

- Uruburu, p.181

- Uruburu, p.274

- Uruburu, p.279

- Kuehn, Henry H. (28 April 2017). Architects' Gravesites: A Serendipitous Guide. MIT Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-262-34074-8.

- Uruburu, p.319

- Uruburu, p.318

- Uruburu, p.307

- Uruburu, pp.306-307

- Uruburu, p.330

- The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing at the TCM Movie Database

- Ragtime at AllMovie

- Ragtime at the Internet Broadway Database

- "My Sweetheart's the Man in the Moon". Samuel French, Inc. Retrieved 2018-06-23.

- Jenkins, Mark (August 14, 2008) "'Girl Cut in Two': An Old Scandal, Stylishly Redressed" NPR

Bibliography

- Baker, Paul R., Stanny: The Gilded Life of Stanford White, The Free Press, NY 1989

- Baatz, Simon, The Girl on the Velvet Swing: Sex, Murder, and Madness at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century (New York: Little, Brown, 2018) ISBN 978-0316396653

- Collins, Frederick L., Glamorous Sinners

- Craven, Wayne. Stanford White: Decorator in Opulence and Dealer in Antiquities, 2005

- Lessard, Suzannah, The Architect of Desire: Beauty and Danger in the Stanford White Family, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London 1997 (written by White's great-granddaughter, a Whiting Award-winning writer for The New Yorker)

- Langford, Gerald, The Murder of Stanford White

- Mooney, Michael, Evelyn Nesbit and Stanford White: Love and Death in the Gilded Age, New York, Morrow, 1976

- Roth, Leland M., McKim, Mead & White, Architects, Harper & Row, Publishers, NY 1983

- Samuels, Charles, The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing

- Nesbit, Evelyn, The Story of My Life 1914

- Nesbit, Evelyn, Prodigal Days 1934

- Thaw, Harry, The Traitor

- Uruburu, Paula, American Eve: Evelyn Nesbit, Stanford White, The Birth of the "It" Girl and the Crime of the Century Riverhead 2008

- White, Samuel G. with Wallen, Jonathan(photographer). The Houses of McKim, Mead and White 1998

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stanford White. |

- Stanford White Papers,1873–1928 New-York Historical Society

- "Stanford White on Long Island" a museum essay on White's residential projects

- New York Architecture Images-New York Architects-McKim, Mead, and White Firm history with images

- Stanford White at Find a Grave

- Gilding the Gilded Age: Interior Decoration Tastes & Trends in New York City A collaboration between The Frick Collection and The William Randolph Hearst Archive at LIU Post.

- "Works of Art from the Collection of Stanford White", The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Archives. Digital images of a scrapbook compiled by Lawrence Grant White, son of Stanford White, on works of art collected by Stanford White, including paintings, sculpture, rugs, tapestries, and other decorative arts.

- "Catalogue of Works of Art at 'Box Hill', St. James, Long Island", The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Archives. Pdf scan of inventory of works of art at Box Hill, the former Stanford White estate in Long Island, completed in 1942.

- The McKim Mead & White Architectural Records Collection at the New York Historical Society

- Stanford White correspondence and architectural drawings, 1887-1922, (bulk 1887-1907), held by the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University