Ivan Aivazovsky

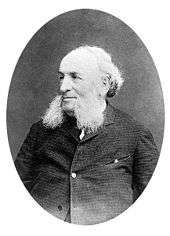

Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky (Russian: Иван Константинович Айвазовский; 29 July 1817 – 2 May 1900) was a Russian Romantic painter who is considered one of the greatest masters of marine art. Baptized as Hovhannes Aivazian, he was born into an Armenian family in the Black Sea port of Feodosia in Crimea and was mostly based there.

Ivan Aivazovsky | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Hovhannes Aivazian (baptized) 29 July [O.S. 17 July] 1817 |

| Died | 2 May [O.S. 19 April] 1900 (aged 82) Feodosia, Russian Empire |

| Resting place | St. Sargis Armenian Church, Feodosia |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Education | Imperial Academy of Arts (1839) |

| Known for | Painting, drawing |

| Movement | Late Romanticism[2] |

| Spouse(s) | Julia Graves (1848–77) Anna Burnazian (1882–1900) |

| Awards | see below |

Following his education at the Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg, Aivazovsky traveled to Europe and lived briefly in Italy in the early 1840s. He then returned to Russia and was appointed the main painter of the Russian Navy. Aivazovsky had close ties with the military and political elite of the Russian Empire and often attended military maneuvers. He was sponsored by the state and was well-regarded during his lifetime. The saying "worthy of Aivazovsky's brush", popularized by Anton Chekhov, was used in Russia for describing something lovely. He remains highly popular in Russia in the 21st century.[3]

One of the most prominent Russian artists of his time, Aivazovsky was also popular outside Russia. He held numerous solo exhibitions in Europe and the United States. During his almost 60-year career, he created around 6,000 paintings, making him one of the most prolific artists of his time.[4][5] The vast majority of his works are seascapes, but he often depicted battle scenes, Armenian themes, and portraiture. Most of Aivazovsky's works are kept in Russian, Ukrainian and Armenian museums as well as private collections.

Life

Background

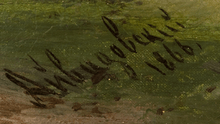

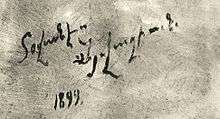

Ivan Aivazovsky was born on 17 July (29 in New Style) 1817 in the city of Feodosia (Theodosia), Crimea, Russian Empire.[7] In the baptismal records of the local St. Sargis Armenian Apostolic Church, Aivazovsky was listed as Hovhannes, son of Gevorg Aivazian (Armenian: Գէորգ Այվազեանի որդի Յօհաննեսն).[8] During his study at the Imperial Academy of Arts, he was known in Russian as Ivan Gaivazovsky (Иванъ Гайвазовскій in the pre-1918 spelling).[9] He became known as Aivazovsky since c. 1840, while in Italy.[10] He signed an 1844 letter with an Italianized rendition of his name: "Giovani Aivazovsky".[11]

His father, Konstantin, (c. 1765–1840),[12] was an Armenian merchant from the Polish region of Galicia. His family had migrated to Europe from Western Armenia in the 18th century. After numerous familial conflicts, Konstantin left Galicia for Moldavia, later moving to Bukovina, before settling in Feodosia in the early 1800s.[13] He was initially known as Gevorg Aivazian (Haivazian or Haivazi), but he changed his last name to Gaivazovsky by adding the Polish "-sky". Aivazovsky's mother, Ripsime, was a Feodosia Armenian. The couple had five children—three daughters and two sons.[13] Aivazovsky's elder brother, Gabriel, was a prominent historian and an Armenian Apostolic archbishop.[14][15]

Education

The young Aivazovsky received parochial education at Feodosia's St. Sargis Armenian Church.[16] He was taught drawing by Jacob Koch, a local architect. Aivazovsky moved to Simferopol with Taurida Governor Alexander Kaznacheyev's family in 1830 and attended the city's Russian gymnasium.[17] In 1833, Aivazovsky arrived in the Russian capital, Saint Petersburg, to study at the Imperial Academy of Arts in Maxim Vorobiev's landscape class. In 1835, he was awarded with a silver medal and appointed assistant to the French painter Philippe Tanneur (fr).[18] In September 1836, Aivazovsky met Russia's national poet Alexander Pushkin during the latter's visit to the Academy.[19][20] In 1837, Aivazovsky joined the battle-painting class of Alexander Sauerweid and participated in Baltic Fleet exercises in the Gulf of Finland.[21] In October 1837, he graduated from the Imperial Academy of Arts with a gold medal, two years earlier than intended.[22][16][4] Aivazovsky returned to Feodosia in 1838 and spent two years in his native Crimea.[13][21] In 1839, he took part in military exercises in the shores of Crimea, where he met Russian admirals Mikhail Lazarev, Pavel Nakhimov and Vladimir Kornilov.[7][23]

First visit to Europe

In 1840, Aivazovsky was sent by the Imperial Academy of Arts to study in Europe.[22][21] He first traveled to Venice via Berlin and Vienna and visited San Lazzaro degli Armeni, where an important Armenian Catholic congregation was located and his brother Gabriel lived at the time. Aivazovsky studied Armenian manuscripts and became familiar with Armenian art.[24] He met Russian novelist Nikolai Gogol in Venice. He then headed to Florence, Amalfi and Sorrento. In Florence, he met painter Alexander Ivanov.[21] He remained in Naples and Rome between 1840 and 1842. Aivazovsky was heavily influenced by Italian art and their museums became the "second academy" for him.[24] According to Rogachevsky the news of successful exhibitions in Italy reached Russia.[4] Pope Gregory XVI awarded him with a golden medal.[25] He then visited Switzerland, Germany, the Netherlands and Britain, where he met English painter J. M. W. Turner who, "was so struck by Aivazovsky's picture The Bay of Naples on a Moonlit Night that he dedicated a rhymed eulogy in Italian to Aivazovsky."[23][21] In an international exhibition at the Louvre, he was the only representative from Russia.[24] In France, he received a gold medal from the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture. He then returned to Naples via Marseille and again visited Britain, Portugal, Spain, and Malta in 1843. Aivazovsky was admired throughout Europe.[23] He returned to Russia via Paris and Amsterdam in 1844.[23]

Return to Russia and first marriage

Upon his return to Russia, Aivazovsky was made an academician of the Imperial Academy of Arts and was appointed the "official artist of the Russian Navy to paint seascapes, coastal scenes and naval battles."[18][21] In 1845, Aivazovsky traveled to the Aegean Sea with Duke Konstantin Nikolayevich and visited the Ottoman capital, Constantinople, and the Greek islands of Patmos and Rhodes.[21]

In 1845, Aivazovsky settled in his hometown of Feodosia, where he built a house and studio.[7][21] He isolated himself from the outside world, keeping a small circle of friends and relatives.[24] Yet the solitude played a negative role in his art career. By the mid-nineteenth century, Russian art was moving from Romanticism towards a distinct Russian style of Realism, while Aivazovsky continued to paint Romantic seascapes and attracted heavy criticism.[24]

In 1845 and 1846, Aivazovsky attended the maneuvers of the Black Sea Fleet and the Baltic Fleet at Petergof, near the imperial palace. In 1847, he was given the title of professor of seascape painting by the Imperial Academy of Arts and elevated to the rank of nobility. In the same year, he was elected to the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.[21]

In 1848, Aivazovsky married Julia Graves, an English governess. They had four daughters: Elena (1849), Maria (1851), Alexandra (1852) and Joanne (1858). They separated in 1860 and divorced in 1877 with permission from the Armenian Church, since Graves was a Lutheran.[21][26]

Rise to prominence

In 1851, traveling with the Russian emperor Nicholas I, Aivazovsky sailed to Sevastopol to participate in military maneuvers. His archaeological excavations near Feodosia lead to his election as a full member of the Russian Geographical Society in 1853. In that year, the Crimean War erupted between Russia and the Ottoman Empire, and he was evacuated to Kharkiv. While safe, he returned to the besieged fortress of Sevastopol to paint battle scenes.[25] His work was exhibited in Sevastopol while it was under Ottoman siege.[25]

Between 1856 and 1857, Aivazovsky worked in Paris and became the first Russian[27] (and the first non-French) artist to receive the Legion of Honour. In 1857, Aivazovsky visited Constantinople and was awarded the Order of the Medjidie. In the same year, he was elected an honorary member of the Moscow Art Society. He was awarded the Greek Order of the Redeemer in 1859 and the Russian Order of St. Vladimir in 1865.[25]

Aivazovsky opened an art studio in Feodosia in 1865 and was awarded a salary by the Imperial Academy of Arts the same year.[21]

Travels and accolades: 1860s–1880s

In the 1860s, the artist produced several paintings inspired by Greek nationalism and the Italian unification.[7][25] In 1868, he once again visited Constantinople and produced a series of works about the Greek resistance to the Turks, during the Great Cretan Revolution.[21] In 1868, Aivazovsky traveled in the Caucasus and visited the Russian part of Armenia for the first time. He painted several mountainous landscapes and in 1869 held an exhibition in Tiflis.[7] Later in the year, he made a trip to Egypt and took part in the opening ceremony of the Suez Canal. He became the "first artist to paint the Suez Canal, thus marking an epoch-making event in the history of Europe, Africa and Asia."[25][28]

In 1870, Aivazovsky was made an Actual Civil Councilor, the fourth highest civil rank in Russia.[21] In 1871, he initiated the construction of the archaeological museum in Feodosia.[25] In 1872, he traveled to Nice and Florence to exhibit his paintings.[25] In 1874, the Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze (Florence Academy of Fine Art) asked him for a self-portrait to be hung in the Uffizi Gallery.[29][30] The same year, Aivazovsky was invited to Constantinople by Sultan Abdülaziz who subsequently bestowed upon him the Turkish Order of Osmanieh.[21] In 1876, he was made a member of the Academy of Arts in Florence and became the second Russian artist (after Orest Kiprensky) to paint a self-portrait for the Palazzo Pitti.[24][25]

Aivazovsky was elected an honorary member of Stuttgart's Royal Academy of Fine Arts (de) in 1878. He made a trip to the Netherlands and France, staying briefly in Frankfurt until 1879. He then visited Munich and traveled to Genoa and Venice "to collect material on the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus."[25]

In 1880, Aivazovsky opened an art gallery in his Feodosia house; it became the third museum in the Russian Empire, after the Hermitage Museum and the Tretyakov Gallery.[24][25] Aivazovsky held an 1881 exhibition at London's Pall Mall, attended by English painter John Everett Millais and Edward VII, Prince of Wales.[21]

Second marriage and later life

Aivazovsky's second wife, Anna Burnazian, was a young Armenian widow 40 years his junior.[31] Aivazovsky said that by marrying her in 1882, he "became closer to [his] nation", referring to the Armenian people.[26] In 1882, Aivazovsky visited Moscow and St Petersburg and then toured the countryside of Russia by traveling along the Volga River in 1884.[21][25]

In 1885, he was promoted to the rank of Privy Councilor. The next year, the 50th anniversary of his creative labors, was celebrated with an exhibition in St Petersburg, and an honorary membership in the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts.[18][25]

After meeting Aivazovsky in person, Anton Chekhov wrote a letter to his wife on 22 July 1888 describing him as follows:[32][33]

Aivazovsky himself is a hale and hearty old man of about seventy-five, looking like an insignificant Armenian and an bishop; he is full of a sense of his own importance, has soft hands and shakes your hand like a general. He's not very bright, but he is a complex personality, worthy of a further study. In him alone there are combined a general, a bishop, an artist, an Armenian, an naive old peasant, and an Othello.

After traveling to Paris with his wife, in 1892 he made a trip to the United States, visiting Niagara Falls in New York and Washington D.C.[25] In 1896, at 79, Aivazovsky was promoted to the rank of full privy councillor.[21]

Aivazovsky was deeply affected by the Hamidian massacres that took place in the Armenian-inhabited areas of the Ottoman Empire between 1894 and 1896. He painted a number of works on the subject such as The Expulsion of the Turkish Ship, and The Armenian Massacres at Trebizond (1895). He threw the medals given to him by the Ottoman Sultan into the sea and told the Turkish consul in Feodosia: "Tell your bloodthirsty master that I've thrown away all the medals given to me, here are their ribbons, send it to him and if he wants, he can throw them into the seas painted by me."[34] He created several other paintings capturing the events, such as Lonely Ship and Night. Tragedy in the Sea of Marmara (1897).[35][36]

He spent his final years in Feodosia. In the 1890s, thanks to his efforts a commercial port was established in Feodosia and linked to the railway network of the Russian Empire.[31][37] The railway station, opened in 1892, is now called Ayvazovskaya and is one of the two stations within the city of Feodosia. Aivazovsky also supplied Feodosia with drinking water.[38][39]

Death

Aivazovsky died on 19 April (2 May in New Style) 1900 in Feodosia.[25] In accordance with his wishes, he was buried at the courtyard of St. Sargis Armenian Church.[40] A white marble sarcophagus was made by Italian sculptor L. Biogiolli in 1901.[41] A quote from Movses Khorenatsi's History of Armenia in Classical Armenian is engraved on his tombstone: Մահկանացու ծնեալ անմահ զիւրն յիշատակ եթող (Mahkanatsu tsneal anmah ziurn yishatak yetogh),[42] which translates: "He was born a mortal, left an immortal legacy"[40] or "Born as a mortal, left the immortal memory of himself".[43] The Russian inscription beneath reads: Профессоръ Иванъ Константиновичъ АЙВАЗОВСКIЙ 1817—1900, "Professor Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky 1817-1900".

After his death, his wife Anna led a generally secluded life, living in several rooms she had retained after nationalization, until 1941.[44] She died on 25 July 1944 and was buried next to Aivazovsky.[31] Two of his daughters (Maria and Alexandra) left Russia following the Revolution of 1917, while the other two died shortly thereafter: Yelena in 1918 and Zhanna in 1922.[44]

Art

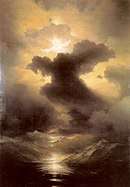

During his 60-year career, Aivazovsky produced around 6,000 paintings[18][25][48] of, what one online art magazine describes, "very different value ... there are masterpieces and there are very timid works".[49] However, according to one count as many as 20,000 paintings are attributed to him.[50] The vast majority of Aivazovsky's works depict the sea.[51] He rarely drew dry-landscapes and created only a handful of portraits.[49] According to Rosa Newmarch Aivazovsky "never painted his pictures from nature, always from memory, and far away from the seaboard."[52] Rogachevsky wrote that "His artistic memory was legendary. He was able to reproduce what he had seen only for a very short time, without even drawing preliminary sketches."[25] Bolton praised "his ability to convey the effect of moving water and of reflected sun and moonlight."[22]

Exhibitions

He held 55 solo exhibitions (an unprecedented number)[53] over the course of his career. Among the most notable were held in Rome, Naples and Venice (1841–42), Paris (1843, 1890), Amsterdam (1844), Moscow (1848, 1851, 1886), Sevastopol (1854), Tiflis (1868), Florence (1874), St. Petersburg (1875, 1877, 1886, 1891), Frankfurt (1879), Stuttgart (1879), London (1881), Berlin (1885, 1890), Warsaw (1885), Constantinople (1888), New York (1893), Chicago (1893), San Francisco (1893).[21]

He also "contributed to the exhibitions of the Imperial Academy of Arts (1836–1900), Paris Salon (1843, 1879), Society of Exhibitions of Works of Art (1876–83), Moscow Society of Lovers of the Arts (1880), Pan-Russian Exhibitions in Moscow (1882) and Nizhny Novgorod (1896), World Exhibitions in Paris (1855, 1867, 1878), London (1863), Munich (1879) and Chicago (1893) and the international exhibitions in Philadelphia (1876), Munich (1879) and Berlin (1896)."[21]

Style

A primarily Romantic painter, Aivazovsky used some Realistic elements.[54] Leek argued that Aivazovsky remained faithful to Romanticism throughout his life, "even though he oriented his work toward the Realist genre."[4] His early works are influenced by his Academy of Arts teachers Maxim Vorobiev and Sylvester Shchedrin.[18] Classic painters like Salvator Rosa, Jacob Isaacksz van Ruisdael and Claude Lorrain contributed to Aivazovsky's individual process and style.[7] Karl Bryullov, best known for his The Last Day of Pompeii, "played an important part in stimulating Aivazovsky's own creative development," according to Bolton.[22][18] Aivazovsky's best paintings in the 1840s–1850s used a variety of colors and were both epic and romantic in theme.[7] Newmarch suggested that by the mid-19th century the romantic features in Aivazovsky's work became "increasingly pronounced."[49] She, like most scholars, considered his Ninth Wave his best piece of art and argued that it "seems to mark the transition between fantastic color of his earlier works, and the more truthful vision of the later years."[55] By the 1870s, his paintings were dominated by delicate colors; and in the last two decades of his life, Aivazovsky created a series of silver-toned seascapes.[7]

The distinct transition in Russian art from Romanticism to Realism in the mid-nineteenth century left Aivazovsky, who would always retain a Romantic style, open to criticism. Proposed reasons for his unwillingness or inability to change began with his location; Feodosia was a remote town in the huge Russian empire, far from Moscow and Saint Petersburg. His mindset and worldview were similarly considered old-fashioned and did not correspond to the developments in Russian art and culture.[24] Vladimir Stasov only accepted his early works, while Alexandre Benois wrote in his The History of Russian Painting in the 19th Century that despite being Vorobiev's student, Aivazovsky stood apart from the general development of the Russian landscape school.[24]

Aivazovsky's later work contained dramatic scenes and was usually done on a larger scale. He depicted "the romantic struggle between man and the elements in the form of the sea (The Rainbow, 1873), and so-called "blue marines" (The Bay of Naples in Early Morning, 1897, Disaster, 1898) and urban landscapes (Moonlit Night on the Bosphorus, 1894)."[18]

Landscapes

Azure Grotto, Naples (1841)

Azure Grotto, Naples (1841) The Galata Tower by Moonlight (1845)

The Galata Tower by Moonlight (1845) View of Constantinople, with the newly-constructed Ortaköy Mosque (1856)

View of Constantinople, with the newly-constructed Ortaköy Mosque (1856)- View of Tiflis (1869)

- Moscow in Winter from the Sparrow Hills (1872)

Seascapes

Night at Gurzuf

Night at Gurzuf Battle of Navarino (1848)

Battle of Navarino (1848).jpg) The brig Mercury encounter after defeating two Turkish ships of the Russian squadron (1848)

The brig Mercury encounter after defeating two Turkish ships of the Russian squadron (1848) Bracing The Waves

Bracing The Waves- Battle of Çesme at Night (1856)

Bay of Naples (1842)

Bay of Naples (1842) American Shipping off the Rock of Gibraltar (1873)

American Shipping off the Rock of Gibraltar (1873)_%D0%98%D0%B2%D0%B0%D0%BD_(%D0%9E%D0%B3%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B5%D1%81)_%D0%9A%D0%BE%D0%BD%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%BD%D1%82%D0%B8%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%B8%D1%87_%D0%A0%D0%B0%D0%B4%D1%83%D0%B3%D0%B0.jpg) Rainbow (1873)

Rainbow (1873) Ship "Twelve Apostles" (1878)

Ship "Twelve Apostles" (1878) Sea coast at night. Near the beacon

Sea coast at night. Near the beacon Seascape with a steamer (1886)

Seascape with a steamer (1886) Tempest by Sounion, (1856)

Tempest by Sounion, (1856) The Wrath Of The Seas (1886)

The Wrath Of The Seas (1886)

- Lake Maggiore in the Evening (1892)

Religious paintings

Chaos (1841)

Chaos (1841) Jesus walking on water (1888)

Jesus walking on water (1888) Jesus walking on water (1890)

Jesus walking on water (1890) Passage of the Jews through the Red Sea (1891)

Passage of the Jews through the Red Sea (1891)

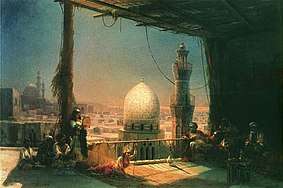

Orientalist themes

Bosphorus

Bosphorus_%D0%98%D0%B2%D0%B0%D0%BD_(%D0%9E%D0%B3%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B5%D1%81)_%D0%9A%D0%BE%D0%BD%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%BD%D1%82%D0%B8%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%B8%D1%87_%D0%9B%D1%83%D0%BD%D0%BD%D0%B0%D1%8F_%D0%BD%D0%BE%D1%87%D1%8C_%D0%BD%D0%B0_%D0%91%D0%BE%D1%81%D1%84%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%B5.jpg) A Moonlit Night on the Bosphorus

A Moonlit Night on the Bosphorus

View of Constantinopole by Evening Light

View of Constantinopole by Evening Light Scenes from Cairo's Life

Scenes from Cairo's Life- Boat Ride by Kumkapı in Constantinople

- Sunset over the Golden Horn

- Dusk on the Golden Horn

Trebizond

Trebizond- Coffee-house by the Ortaköy Mosque in Constantinople

.jpg) The Great Pyramid of Giza

The Great Pyramid of Giza Tower

Tower

Armenian themes

Aivazovsky's early works incorporated Armenian themes. The artist's longstanding wish to visit his ancestral homeland was fulfilled in 1868. During his visit to Russian (Eastern) Armenia (roughly corresponding to the modern Armenia, as opposed to Western Armenia under Ottoman rule), Aivazovsky created paintings of Mount Ararat, the Ararat plain, and Lake Sevan. Although Mt. Ararat has been depicted in paintings of many non-native artists (mostly European travelers), Aivazovsky became the first Armenian artist to illustrate the two-peaked biblical mountain.[56][24]

He resumed the creation of Armenian-related paintings in the 1880s: Valley of Mount Ararat (1882), Ararat (1887), Descent of Noah from Ararat (1889).[56] The unique Valley of Mount Ararat contains Aivazovksy's signature in Armenian: "Aivazian" (Այվազեան).[56][26] In a panorama of Venice expressed by Byron's Visit to the Mekhitarists on St Lazarus Island in Venice (1898); the foreground of the picture contains members of the Armenian Congregation giving an enthusiastic welcome to the poet.[57]

His other themed works from this period include rare portraits of notable Armenians, such as his brother Archbishop Gabriel Aivazovsky (1882), Count Mikhail Loris-Melikov (1888), Catholicos Mkrtich Khrimian (1895), Nakhichevan-on-Don Mayor Аrutyun Khalabyan and others.[56][24]

The Baptism of Armenians and Oath Before the Battle of Avarayr (both 1892) depict the two single most memorable events of ancient Armenia: the Christianization of Armenia via baptism of King Tiridates III (early 4th century), and the Battle of Avarayr of 451.[24]

.jpg) Valley of Mount Ararat (1882)

Valley of Mount Ararat (1882) The Baptism of the Armenian People (1892)

The Baptism of the Armenian People (1892) Descent of Noah from Ararat (1889), National Gallery of Armenia[58]

Descent of Noah from Ararat (1889), National Gallery of Armenia[58] Oath Before the Battle of Avarayr (1892)

Oath Before the Battle of Avarayr (1892).jpg)

Aivazovsky and archaeology

.jpg)

Aivazovsky took an interest in archaeology since the 1850s. He employed farmers to conduct archaeological excavations in the Feodosia area. In 1853 some 22 burial mounds were excavated on Mount Tepe-Oba, which mostly contained broken amphorae and bones, but also golden necklaces, earrings, a female head, a chain with a sphinx, a sphinx with woman's head, the head of an ox, slabs; silver bracelets; clay statuettes, medallions, various vessels, a sarcophagus; silver and bronze coins. The site has been dated to the 5th to 3rd centuries BC when there was an ancient Greek settlement of Theodosia. The best finds were sent by Aivazovsky to the Imperial Hermitage in Petersburg.[60] In 1871 he founded the construction of a new Museum of Antiquities on Mount Mithridat modeled after a typical Ancient Greek temple of the Doric order. It was destroyed during World War II.[60]

Aivazovsky's estates

Aivazovsky was a major landowner who owned numerous estates in the eastern part of Crimea, mostly located not far from Feodosia. These estates delivered him significant income; more than the sale of his paintings. His earliest major estate, bestowed by the Emperor in 1848 along with a personal noble title, was the one at Shakh-Mamai (now called Ayvazovskoye). Located some 25 kilometres (16 mi) from Feodosia, it initially covered an area of 2,500 diasiatins (around 2,725 hectares (6,730 acres)). The estate had an Eastern-style house, and one of its most prominent visitors, Anton Chekhov, wrote that "It is an extravagant, fairy-tale estate of the kind you must probably find in Persia." By the end of his life, the state had grown to include some 6,000 diasiatins of land, a dairy farm, and a steam-powered mill.[44]

The second major estate, located in Subash (now Zolotoy Klyuch), contained some 2,500 diasiatins of land. The site contained several natural springs, which Aivazovsky acquired in 1852 from the Lansky family. The latter also sold Aivazovsky 2,362 diasiatins of land. Later, Aivazovsky supplied Feodosia with water from Subash. In both estates, vegetables were grown. He had small estates in Romash-Eli (now Romanovka), with 338 diasiatins of land covered with orchards, and the Sudak Valley, with 12 diasiatins of vineyard, along with a dacha (summer house).[44]

In Feodosia, Aivazovsky possessed a house and a vineyard. He also owned houses elsewhere in Crimea, such as Stary Krym and Yalta. The estates inherited by his heirs were lost in the early Soviet period when they were nationalized.[44]

Influence

Aivazovsky was the most influential seascape painter in nineteenth-century Russian art.[18] According to the Russian Museum, "he was the first and for a long time the only representative of seascape painting" and "all other artists who painted seascapes were either his own students or influenced by him."[53]

Arkhip Kuindzhi (1841/2–1910) is cited by Krugosvet encyclopedia as having been influenced by Aivazovsky.[61] In 1855, at age 13–14, Kuindzhi visited Feodosia to study with Aivazovsky, however, he was engaged merely to mix paints[62] and instead studied with Adolf Fessler, Aivazovsky's student.[63] A 1903 encyclopedic article stated: "Although Kuindzhi cannot be called a student of Aivazovsky, the latter had without doubt some influence on him in the first period of his activity; from whom he borrowed much in the manner of painting."[64] English art historian John E. Bowlt wrote that "the elemental sense of light and form associated with Aivazovsky's sunsets, storms, and surging oceans permanently influenced the young Kuindzhi."[62]

Aivazovsky also influenced Russian painters Lev Lagorio, Mikhail Latri, and Aleksey Ganzen (the latter two were his grandsons).[27]

Recognition

Ivan Aivazovsky is one of the few Russian artists to achieve wide recognition during his lifetime.[18][4][65] Today, he is considered as one of the most prominent marine artists of the 19th century,[40][66][67] and, overall, one of the greatest marine artists in Russia and the world.[29][68][69][70][71] Aivazovsky was also one of the few Russian artists to become famous outside Russia.[72][73][74] In 1898, Munsey's Magazine wrote that Aivazovsky is "better known to the world at large than any other artist of his nationality, with the exception of the sensational Verestchagin".[75] However, according to art historian Janet Whitmore he is relatively unknown in the west.[37] Art historian Rosalind Polly Blakesley noted in a 2003 book review that Aivazovsky has not been incorporated into the mainstream Western history of art.[76]

In Russia

In a July 2017 poll conducted by the VTsIOM Aivazovsky ranked first as the most favorite artist with 27% of respondents naming him as their favorite, ahead of Ivan Shishkin (26%) and Ilya Repin (16%). Overall, 93% of respondents said they were familiar with his name (26% knew him well, 67% have heard his name) and 63% of those who know him said they liked his works, including 80% of those 60 or older and 35% of 18 to 24 year olds.[3][77]

In 1890, the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary described him as the "best Russian marine painter".[78] Ivan Kramskoi, one of the most prominent Russian artists of the nineteenth century, praised him thus: "Aivazovsky is—no matter who says what—a star of first magnitude, and not only in our [country], but also in history of art in general."[6][60] Another Russian painter, Alexandre Benois, suggested that "Aivazovsky stands apart from the general history of the Russian school of landscape painting."[53] The State Russian Museum website continues, "It is hard to find another figure in the history of Russian art enjoying the same popularity among amateur viewers and erudite professionals alike."[53] Writing in 1861 in the magazine Vremya, Fyodor Dostoyevsky compared Aivazovsky's work with that of Alexandre Dumas as both artists "produce a remarkably striking effect: remarkable indeed, as neither man ever produces anything ordinary at all. Ordinary things, they despise. Their compositions are certainly quite fascinating. The books of Dumas were devoured with impatience; the paintings of Aivazovsky have been selling like hot cakes. Both produce works that are not dissimilar to fairy tales: fireworks, clatter, screams, howling winds, lightning."[79]

In nineteenth-century Russia, his name became a synonym for art and beauty. The phrase "worthy of Aivazovsky's brush" was the standard way of describing something ineffably lovely. It was first used by Anton Chekhov in his 1897 play Uncle Vanya.[32] In response to Marina Timofeevna's (the old nurse) query about the fight between Ivan Voynitsky ("Uncle Vanya") and Aleksandr Serebryakov, Ilya Telegin says that it was "A sight[lower-alpha 1] worthy of Aivazovsky's brush" (Сюжет, достойный кисти Айвазовского Syuzhet, dostoyniy kisti Ayvazovskovo).[83]

A street in Moscow (ru) was named after Aivazovsky in 1978.[84] His first and only statue in Russia was erected in 2007 in Kronstadt, near Saint Petersburg.[85] The Simferopol International Airport in Crimea, under Russian administration, was voted to be named after Aivazovsky in 2018.[86][87] It was officially renamed according to a decree signed by President Vladimir Putin on May 31, 2019 and ceremonially renamed on Russia Day (June 12).[88][89]

In Armenia

Aivazovsky has always been considered an Armenian painter in his ancestral homeland[24] and virtually always referred to there by his Armenian name, Hovhannes.[92] Virtually all Armenian, some Russian[93] and English[5] sources, refer to him as Hovhannes Ayvazovski (Armenian: Հովհաննես Այվազովսկի; Russian: Ован(н)ес Айвазовский, Ovan(n)es Aivazovsky).[6][94] The artist signed some of his paintings and letters in Armenian.[95] For instance, his signatures in both Armenian (Այվազեան, Ayvazean) and Russian (Айвазовскій, Ayvazovskiy) appear on Valley of Mount Ararat (1882).[10]

Aivazovsky has been described as the "most remarkable" Armenian painter of the 19th century and the first-ever Armenian marine painter.[5][96] He was born outside Armenia proper, and like his contemporaries, including Gevorg Bashinjaghian, Panos Terlemezian, and Vardges Sureniants, Aivazovsky lived outside his homeland, drawing primary influences from European and Russian schools of art. His creativity and viewpoint have been attributed to his uniquely Armenian roots. According to Sureniants, he sought to create a union which would have brought together all Armenian artists around the world.[24] The prominent Armenian poet Hovhannes Tumanyan wrote a short poem titled "In Front of an Aiazovsky painting" («Այվազովսկու նկարի առջև») in 1893. It is inspired by painting of the sea by Aivazovsky, mostly likely from the 1870s–1890s.[97] It was translated into English in 1917 by Alice Stone Blackwell.[98]

Several paintings of Aivazovsky from the National Gallery of Armenia hang in the Presidential Palace in Yerevan.[99]

In Ukraine

In Ukraine, he is sometimes considered a Ukrainian painter.[100] He was included in a 2001 book titled 100 Greatest Ukrainians.[101] An alley in Kiev (Провулок Айвазовського) was named after him in 1939. A three-star hotel in Odessa, where dozens of reproductions of his works are displayed, is named for him as well.[102] A statue of Aivazovsky and his brother Gabriel is located in Simferopol, Crimea's administrative center.[103] In June 2017 Ukrainian president Petro Poroshenko claimed that Aivazovsky is "part of Ukrainian heritage."[104][105] Russian media accused him of appropriation of Aivazovsky.[106][107]

In Turkey

Aivazovsky's painting were popular in the Ottoman imperial court during the 19th century.[108] According to Hürriyet Daily News, as of 2014, 30 paintings of Aivazovsky are on display in museums in Turkey.[109] According to Bülent Özükan, there are 41 paintings of Aivazovsky on display in Turkey, 21 in former palaces of Ottoman sultans, 10 in various marine and military museums, and 10 at the presidential residence.[110] In 2007, when Abdullah Gül became president of Turkey, he brought paintings by Aivazovsky up from the basement to hang in his office during redecoration of the presidential palace, the Çankaya Mansion in Ankara.[111] Pictures of official meetings of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan at the new Presidential Complex in Ankara show that the walls of the rooms at the presidential residence are decorated with Aivazovsky's artwork.[110]

Legacy

Aivazovsky's house in Feodosia, where he had founded an art museum in 1880, is open to this day as the Aivazovsky National Art Gallery. It remains a central attraction in the city[37] and holds the world's largest collections (417) of Aivazovsky paintings.[31] A statue of the artist stands in front.

Posthumous honors

The Soviet Union (1950),[112] Romania (1971),[113][114] Madagascar (1988),[115] Armenia (first in 1992),[116] Russia (1995),[117] Ukraine (1999),[118] Abkhazia (1999),[119] Moldova (2010),[120] Kyrgyzstan (2010),[121] Burundi (2012),[122] and Mozambique (2013)[123] have issued postage stamps depicting Aivazovsky or his works.[113] The minor planet 3787 Aivazovskij, named after Aivazovsky, was discovered by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Chernykh in 1977.[124]

In 2016 and 2017 the 200th anniversary of Aivazovsky was celebrated with major exhibitions in several countries. An exhibition featuring 120 paintings and 55 etchings of Aivazovsky was held at the Tretyakov Gallery on Krymsky Val in Moscow from 29 July to 20 November 2016 dedicated to his 200th anniversary of birth.[125][126] In the first 2 weeks, the exhibition had around 55,000 visitors, a record number.[127] 38 of the works were moved from the Aivazovsky Art Gallery in Feodosia, which prompted Ukraine to call for an international boycott of the Tretyakov Gallery as it considers Crimea an occupied territory.[128] Exhibitions were also held at the National Art Museum of Ukraine in Kiev,[129] and the National Gallery of Armenia in Yerevan.[130]

Auctions

Aivazovsky's paintings began appearing in auctions (mostly in London) in the early 2000s. Many of his works are being bought by Russian oligarchs.[131] His works have risen steadily in auction value.[132] In November 2004, his Saint Isaac's Cathedral On A Frosty Day, a rare cityscape, sold for around £1 million ($2.1 million).[133][134] In 2007, his painting American Shipping off the Rock of Gibraltar auctioned at £2.71 million, "more than four times its top estimate". It was, "the highest price paid at auction for Aivazovsky" at the time.[135] In April 2012, his 1856 work View of Constantinople and the Bosphorus was sold at Sotheby's for a record $5.2 million (£3.2 million),[136] a tenfold increase since it was last at an auction in 1995.[137]

Stolen paintings

In January 2011 a number of paintings, including those of Aivazovsky, were stolen from the country house of Aleksandr Tarantsev, an owner of a chain of jewelry stores in Russia.[138][139] In 2017 it was reported that a fake of one of the paintings stolen from Tarantsev's house was presented to Armenian president Serzh Sargsyan by the Pyunik foundation.[140][141]

In June 2015 Sotheby's withdrew from auction an 1870 Aivazovsky painting Evening in Cairo, which was estimated at £1.5–2 million ($2–$3 million), after the Russian Interior Ministry claimed that it was stolen in 1997 from a private collection in Moscow.[142][143] These allegations were not maintained before the English court, which ordered the return of the painting to the seller. In 2017 View on Revel (1845), stolen from the Dmitrov Kremlin Museum in 1976, was found at Koller Auktionen in Zürich, Switzerland.[144]

Awards

| Country | Year | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Legion of Honor (Chevalier) | 1857[37] | ||

| Order of the Medjidie | 1858 | ||

| Order of the Redeemer | 1859 | ||

| Order of St. Vladimir | 1865 | ||

| Order of Osmanieh | 1874 | ||

| Order of the White Eagle | 1893 | ||

| Order of St. Alexander Nevsky | 1897 | ||

Ranks

- 1870 — Actual Civil Councilor (Действительный статский советник)

- 1885 — Privy Councilor (Тайный советник)

- 1896 — Actual Privy Councilor (Действительный тайный советник)

See also

- Russian culture

- List of Russian artists

- Armenian culture

- Armenians in Crimea

References

Notes

Citations

- Markina, Lyudmila (2017). "The Many Faces of Ivan Aivazovsky". Tretyakov Gallery Magazine. 54 (1).

- "Вера Бодунова: Айвазовский — свой среди чужих". Kommersant (in Russian) (137). 30 July 2016. p. 4.

Это художник, который считается поздним романтиком.

- "Poll reveals Russians enjoy Aivazovsky's paintings more than other artists' works". TASS. 28 July 2017. Archived from the original on 7 December 2017.

- Leek 2012, p. 178.

- Lang, David Marshall (1970). Armenia: Cradle of Civilization (1st ed.). London: Allen & Unwin. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-04-956007-9.

- "Иван Айвазовский – великий маринист [Ivan Aivazovsky – great marinist]" (in Russian). Kommersant Papers. 30 November 2013. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- Ghazarian 1974, pp. 350–351

- Harutiunian 1965, p. 89.

- Petrov, Pyotr (1887). Указатель к Сборнику матеріалов для исторіи Императорской С.-Петербургской Академіи художеств за сто лѣт ея существованія [Index to the collection of materials for the history of the Imperial St. Petersburg Academy of Arts for 100 years of its existence] (in Russian). St. Petersburg: M. M. Stasulevich. p. 51.

- Harutiunian 1965, p. 93.

- "AIVAZOVKSY, Ivan (1817–1900). Autograph letter signed ('Giovani Aivazovsky') to Auguste Vecchy, St Petersburg, 28 August 1844, in eccentric Italian". Christie's. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- Mikaelian 1991, p. 69.

- Sarkssian 1963, p. 25.

- Donenko, Nikolay (2007). Православные монастыри: Симферопольская и Крымская епархия Украинской православной церкви Московского патриархата (in Russian). Sonat. p. 82.

О нем писал армянский епископ Гавриил (Айвазовский), брат выдающегося художника- мариниста...

- "Armenia's in Venice to Highlight Save Venice 2004". Asbarez. 23 March 2004.

The great seascape painter Ivan Aivazovsky (Hovhannes Aivazian)–while visiting his brother Archbishop Gabriel Aivazovsky–immortalized the Island and the Venetian lagoon in numerous magnificent paintings.

- Mikaelian 1991, p. 59.

- Bobkov, V. V. (2010). "Феодосийский Градоначальник Александр Иванович Казначеев: Основные Вехи Административной Деятельности [Feodosia Mayor Alexander Ivanovich Kaznacheyev: Major Milestones In Administrative Activities]" (PDF) (in Russian). Simferopol: Tavrida National V.I. Vernadsky University: 39–40. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2014. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Ayvazovskiy (Gayvazovskiy), Ivan (Oganes) Konstantinovich". Tretyakov Gallery. Archived from the original on 19 March 2014.

- Briggs, A.D.P., ed. (1999). Alexander Pushkin: a celebration of Russia's best-loved writer. London: Hazar Publishing. p. 219. ISBN 1-874371-14-8.

- "Sotheby's Russian Art Evening sale" (PDF). Sotheby's. 9 June 2008. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- "Hovhannes Aivazovsky". RusArtNet.com The Premier Site for Russian Culture. Archived from the original on 19 March 2014.

- Bolton 2010, p. 140.

- Bolton 2010, p. 141.

- Khachatrian "The Sea Poet"

- Rogachevsky, Alexander. "Ivan Aivazovsky (1817–1900)". Tufts University. Archived from the original on 19 March 2014.

- Mikaelian 1991, p. 63.

- Gomtsyan, Natalia (11 September 2015). "Айвазовский и его окружение". Golos Armenii (in Russian).

- Shaljyan, Emma (March 2012). "Walter and Laurel Karabian Speak on Artist Aivazian (Aivazovsky)". Hye Sahrzoom, Armenian Studies Program California State University, Fresno. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

Aivazovsky, in fact, was the first painter to paint the Suez Canal.

- "Ivan Aivazovsky, Seascape at Sunset, 1841" (PDF). Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

Ivan Aivazovsky was the best known Russian painter of seascapes.

- Bird, Alan (1987). A history of Russian painting. Boston: G.K. Hall. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-8161-8911-3.

- Obukhovska, Liudmyla (7 August 2012). "To a good genius ... Feodosiia marked the 195th anniversary of Ivan Aivazovsky's birth". Den.

- Karlinsky, Simon (1999). Anton Chekhov's Life and Thought: Selected Letters and Commentary. Heim, Michael Henry; Karlinsky, Simon (2nd ed.). Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press. pp. 310–311. ISBN 0-8101-1460-7.

- Vasyanin, Andrey (10 August 2016). "Айвазовский на ладони". Rossiyskaya Gazeta (in Russian) (178).

- Harutiunian 1965, pp. 90–91: "Բռնակալության դեմ ի նշան բողոքի, նա բոլոր շքանշանները նետում է ծովը և ապա երիտասարդի աշխուժությամբ դնում է թուրքական հյուպատոսի մոտ ու զայրացած ասում. «Արյունակզակ տիրոջդ ինձի տված պատվանշանները ծովր նետեցի, ահավասիկ անոնց ժապավենները, իրեն ղրկել եթե կուզե թող ինքն ալ իմ պատկերներս ծովը նետե, բայց հոդս չէ, վասն զի անոնց փոխարժեքը ստացուած եմ»։ Ու կը մեկնի։

- Koorghinian 1967, p. 190.

- Sarkssian 1963, p. 31.

- Whitmore, Janet. "Ivan K. Aivazovsky". Rehs Galleries.

- Novouspensky, Nikolay. "Ivan Aivazovsky". artsstudio.com. Archived from the original on 10 September 2012.

- "Моря пламенный поэт. Иван Айвазовский" (in Russian). Russia-K. 2007.

Благодаря ему в Феодосии был создан водопровод, построены морской торговый порт, железная дорога, возведено здание археологического музея и многое другое.

- "Ivan Constantinovich Aivazovsky". Art Renewal Center. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

One of the greatest seascape painters of his time, Aivazovsky conveyed the movement of the waves, the transparent water, the dialogue between sea and sky with virtuoso skill and tangible verisimilitude.

- Yefremova, Svetlana (24 July 2008). Оставил о себе бессмертную память. Respublika Krym (in Russian). Archived from the original on 19 March 2014.

- "Այվազովսկի Հովհաննես Կոստանդնի [Aivazovsky Hovhannes Konstandni]" (in Armenian). National Gallery of Armenia. Archived from the original on 19 March 2014.

- Minasyan, Artavazd M.; Gevorkyan, Aleksadr V. (2008). How Did I Survive?. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-84718-601-0. OCLC 318443997.

Aivazovsky, Ivan Konstantionvich (real name: Hovannes Gevorgovich Aivazyan) (1817–1900) – grand Russian artist-painter of seascapes, ethnic Armenian. Aside from his artwork, I.A. was also known for his valuable contributions to the developments of the Russian and Armenian cultures of the 19th century. He lived and worked in Feodosia, Crimea. He was buried there according to his will. A sign on his tombstone, written in ancient Armenian, has a quote from the 5th century "History of Armenia" by Moses Khorenatsi says: "Born as a mortal, left the immortal memory of himself."

- Pogrebetskaya, Irina (2017). "Aivazovsky's Estates and Lands". Tretyakov Gallery Magazine. Tretyakov Gallery. 54 (1). Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2019.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link). Originally published in Pogrebetskaya, I.M. 'Aivazovsky’s Estates and Lands' // Materials of research conference “Ivan Aivazovsky’s Artistic Heritage and Traditions”, dedicated to the centenary of Aivazovsky’s death and the 120th anniversary of the Gallery inauguration. Aivazovsky Picture Gallery, Feodosia, 2000. pp. 28-33

- "The Ninth Wave". Hermitage Museum. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- "Aivazovsky, I. K. The Ninth Wave. 1850". Auburn University. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

Detail from "The Ninth Wave" "The Ninth Wave," painted in 1850, is Aivazovsky's most famous work and is an archetypal image for the artist.

- Amirzyanova, Guzel (28 July 2013). Семь знаменитых картин Айвазовского. Komsomolskaya Pravda (in Russian). Archived from the original on 19 March 2014.

Бесспорно, популярнейшей картиной мариниста является «Девятый вал» (1850 г.), сейчас это полотно хранится в Русском музее. Пожалуй, в нем сильнее всего передана романтическая натура художника.

- Sarkssian 1963, p. 26.

- "Ivan Constantinovich Aivazovsky". The Athenaeum: Interactive Humanities Online. Archived from the original on 19 March 2014.

- Nechayev, Sergey (25 July 2015). ""Стахановец" Айвазовский". Sovershenno sekretno (in Russian). 26 (355).

Считается, что кисти Айвазовского принадлежит более 6000 полотен. А приписывают ему и того больше – около 20 000 картин.

- Leek 2012, pp. 178–180.

- Newmarch 1917, p. 192.

- "Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky (1817–1900)". Russian Museum. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- Koorghinian 1967, p. 189.

- Newmarch 1917, p. 191.

- Sarkssian 1963, p. 28.

- Cardwell 2005, p. 402.

- "Նոյն իջնում է Արարատից (1889) [Descent of Noah from Ararat (1889)]" (in Armenian). National Gallery of Armenia. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- Բայրոնի այցը Մխիթարյաններին Սբ. Ղազար կղզում (1899) (in Armenian). National Gallery of Armenia. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- Losev, Dmitry (2017). "Father of the Town: Ivan Aivazovsky and Feodosia: A Lifelong Attachment". Tretyakov Gallery Magazine. Tretyakov Gallery. 54 (1). Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2019.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Куинджи, Архип Иванович" (in Russian). Krugosvet.

Испытал особое влияние И.К.Айвазовского.

- Bowlt, John E. (1975). "A Russian Luminist School? Arkhip Kuindzhi's "Red Sunset on the Dnepr"". Metropolitan Museum Journal. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 10: 123–125. doi:10.2307/1512704. JSTOR 1512704.

- Manin, Vitaly (2000). Архип Куинджи (in Russian). Moskva: Belyĭ gorod. p. 6. ISBN 978-5-7793-0219-7.

в Феодосию к знаменитому Айвазовскому. Куинджи прибыл в тихую Феодосию, по-видимому, летом 1855 года. ... Устройством Куинджи занялся Адольф Фесслер, ученик и копиист Айвазовского. Жил Архип во дворе под навесом в ...

- "Куинджи Архип Иванович". Russian Biographical Dictionary (in Russian). Saint Petersburg: Imperial Russian Historical Society. 1903.

Хотя Куинджи и нельзя назвать учеником Айвазовского, но последний имел на него, несомненно, некоторое влияние в первый период его деятельности; от него он заимствовал многое в манере писать, в выборе тем, в любви к широким пространствам.

online view - According to Aleksey Savinov, an art expert at the Pushkin Museum, see Smirnov, Dmitriy (9 April 2009). "Олигархи покупают Айвазовского по квадратным сантиметрам [Oligarchs buying Aivazovsky's painting by square centimeters]". Komsomolskaya Pravda (in Russian). Retrieved 16 December 2013.

Он был знаменит еще при жизни, он был любимым художником Николая II.

He [Aivazovsky] was famous during his lifetime, he was the favorite artist of Nicholas II. - "Russian Art Sale". Christie's. 18 November 2010. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

Lauded by many as the greatest maritime artist of his time, Aivazovsky's genius lay above all in his capacity for capturing light.

- Chekhonin, O.; Chekhonina, Svetlana; Matafonov, Vadim Stepanovich; Ivashevskaya, Galina (2003). Three centuries of Russian painting (2nd ed.). St. Petersburg: Kitezh Art Publishers. ISBN 978-5-86263-019-0.

The traditions of the genre were brilliantly developed by Ivan Aivazovsky (1817–1900), the most popular artist of the 19th century.

- "Aivazovsky's View of Venice leads Russian art auction at $1.6m". Paul Fraser Collectibles. 29 November 2012. Archived from the original on 19 March 2014.

Aivazovsky (1817–1900) is widely regarded as one of the greatest seascape artists in history...

- Lang, David Marshall (1970). Armenia: Cradle of Civilization. London: Allen & Unwin. p. 245.

Aivazovsky is one of the world's most thrilling masters of the marine picture...

- "Ayvazovskiy (Gayvazovskiy), Ivan (Oganes) Konstantinovich". The State Tretyakov Gallery. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

Aivazovsky was the best known and most celebrated Russian artist of marine paintings.

- Bowater, Marina (1990). Collecting Russian art & antiques. Hippocrene Books. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-87052-897-2.

I. Aivazovsky (1817–1900), the greatest Russian land- and waterscapist — best known for his renderings of the Black Sea.

- "В Вене открылась уникальная выставка работ Ивана Айвазовского [A unique exhibition of works of Ivan Aivazovsky opened in Vienna]". Izvestia (in Russian). 17 March 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

В XIX веке Айвазовский, создавший за свою долгую творческую жизнь около 6 тысяч работ, пользовался огромной популярностью не только в России. Его имя было прекрасно известно любителям живописи в Европе и за океаном.

In the nineteenth century, Aivazovsky, who created about 6 thousand works for his long creative life, was very popular not only in Russia. His name was well known to art lovers in Europe and across the ocean. - Newmarch 1917, pp. 193–194: "one of the few Russian artists whose talent was generally recognized abroad."

- An 1892 The New York Times article describes him as a "celebrated Russian marine artists"; see "Literary and Art Notes" (PDF). New York Times. 3 July 1892.

- "Artists and Their Work". Munsey's Magazine. New York: Frank Munsey. XVIII (4): 488. January 1898.

One of the famous living veterans of the brush is Aivazovsky, the Russian marine painter, whose eightieth birthday was recently celebrated at his native town, Feodosia, the ancient seaport in the Crimea. Aivazovsky, who visited America some years ago, is better known to the world at large than any other artist of his nationality, with the exception of the sensational Verestchagin.

- Blakesley, Rosalind P. (2003). "Reviewed Work: Seas, Cities and Dreams: The Paintings of Ivan Aivazovsky by Gianni Caffiero, Ivan Samarine, Ivan Aivazovsky". The Slavonic and East European Review. 81 (3): 548–549. JSTOR 4213759.

- https://wciom.ru/index.php?id=236&uid=116331

- "Айвазовский". Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary Volume I (in Russian). 1890. pp. 242–243.

- Kalugina, Natalya (2017). "Reporting Aivazovsky in 19th century Russian Periodicals". Tretyakov Gallery Magazine. 54 (1).

- Chekhov, Anton (2010). "Act Four". Five Plays. Brodskaya, Marina (translator). Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-7574-8.

- Frayn, Michael (1988). Plays. Methuen Publishing. p. 361.

- "Soviet Literature" (7–12). Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House: 575. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Сюжет, достойный кисти Айвазовского" (in Russian). Russian Educational Portal, Russian Ministry of Education and Science. Archived from the original on 19 March 2014.

- улица Айвазовского (in Russian). Informative Site of the City of Moscow. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- "В Кронштадте откроют первый в России памятник Ивану Айвазовскому [First statue of Ivan Aivazovsky in Russia to be opened in Kronstadt" (in Russian). Channel One Russia. 15 September 2007. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- "Simferopol airport in Crimea to be named after Aivazovsky". news.am. 5 December 2018.

- Koteneva, Olga (1 December 2018). "Аэропорт Симферополя получит имя художника Айвазовского". Rossiyskaya Gazeta (in Russian).

- "Putin signs executive order on naming Simferopol airport after Hovhannes Aivazovsky". Armenpress. 31 May 2019.

- "Аэропорту Симферополя торжественно присвоено имя Ивана Айвазовского" (in Russian). 1tv.ru. 12 June 2019. Archived from the original on 15 June 2019.

- Keshishyan, A. (2 May 2003). "Այվազովսկին՝ Երեւանում". Aravot (in Armenian).

- "Երեւանում բացվեց Հովհաննես Այվազովսկու արձանը" (in Armenian). Armenpress. 1 May 2003.

- Mahdesian, Arshag D., ed. (1915). "Hovannes Aivazovsky (A Biographical Sketch)". The New Armenia. New York: New Armenia Publishing Company. 8: 362–363.

- The State Russian Museum, where many of his works are located, published an album in 2000 titled "Hovhannes Aivazovsky"; see "Publications / Catalogues and Albums / 2000/". The State Russian Museum. Archived from the original on 21 December 2010. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- "1991–2011 – Национальная галерея Армении [1991–2011 National Gallery of Armenia]" (in Russian). National Gallery of Armenia. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- Adamian 1958, p. 89.

- Sarkissian 1967, p. 70.

- Tumanyan, Hovhannes (1893), Այվազովսկու նկարի առջև (In front of Aiazovsky's painting) (in Armenian). Reproduced in Հովհաննես Թումանյան Երկերի Լիակատար Ժողովածու. Հատոր Առաջին. Քննադատություն և Հրապարակախոսություն 1887–1912 [Anthology of Hovhannes Tumanyan Volume 1: Criticism and Oration 1887–1912] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Armenian National Academy of Sciences. 1994. p. 139.

- Blackwell, Alice Stone (1917). Armenian Poems. Boston: Atlantic Printing Company. p. 187.

- "Demonstration Areas". president.am. Office to the President of the Republic of Armenia.

- "Aivazovsky, Ivan". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. 1984. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- Gnatiuk, Mikhail A.; et al. (2001). Сто великих украинцев [100 Greatest Ukrainians] (in Russian). Kiev: Orfey. ISBN 5-7838-1077-0. OCLC 50599356.

- "Ayvazovsky hotel". Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- See the photo of the statue of Aivazovsky brothers

- Budjurova, Lilia; Shylenko, Olga (28 September 2017). "Ukraine and Russia fight over Crimean heritage". Agence France-Presse.

- "Порошенко об Айвазовском: почтим наше наследие". Ukrayinska Pravda (in Russian). 30 July 2017.

- "Украина присвоила Айвазовского" (in Russian). gazeta.ru. 30 July 2017.

- "Мой друг Иван Айвазовский: Порошенко нашел еще одного "украинца"" (in Russian). RIA Novosti. 31 July 2017.

- İnci Kuyulu Ersoy (April 2005). "Kırım, Feodosiya (Kefe) Ayvazovsky Çeşmesi". Sanat Tarihi Dergisi (in Turkish). Ege University. 14 (1): 193–204. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Naval Museum hosts leading marine artist Aivazovsky". Hürriyet Daily News. 6 January 2014.

- "Aivazovsky's Istanbul: Why Erdogan Loves Paintings by Russian Artist". Sputnik. 30 March 2017.

- Marchand, Laure; Perrier, Guillaume (2015). Turkey and the Armenian Ghost: On the Trail of the Genocide. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-7735-4549-6.

- A 1950 stamp of the Soviet Union depicting Aivazovsky

- Kuzych, Ingert (6 August 2000). "Focus on Philately: Aivazovsky stamps". The Ukrainian Weekly. Archived from the original on 19 March 2014.

- "Romania 1971 Aivazovsky stamp". eBay. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- "Repoblika Demokratika Malagasy 1988 Paositra". Foto.Mail.Ru. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- 1992, 1995

- 1995 stamp

- 1999, 2005

- 1999

- Иван Айвазовский – 110-летие смерти (in Russian). Moldova Stamps. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- 2010

- "Ivan Aivazovsky Burundi stamp". eBay. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- "2013 stamp of Mozambique of Ivan Aivazovsky's pairings". eBay. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- Schmadel, Lutz D. (2012). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (6th ed.). New York: Springer. p. 300. ISBN 978-3-642-29718-2.

- "Иван Айвазовский. К 200-летию со дня рождения [Ivan Aivazovsky. 200 years since birth]". tretyakovgallery.ru (in Russian). Tretyakov Gallery. Archived from the original on 13 August 2016.

- "Tretyakov Gallery celebrates Aivazovsky's 200th birthday with exhibition". Russia Beyond the Headlines. 29 July 2016.

- Medvedeva, Maria (11 August 2016). "Выставка Айвазовского побила рекорд посещаемости выставки Серова" (in Russian). LifeNews.

- Kishkovsky, Sophia (19 August 2016). "Moscow's Tretyakov Gallery under fire over Crimean loans in blockbuster show". The Art Newspaper. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017.

- "Exhibition dedicated to 200th anniversary of Hovhannes (Ivan) Aivazovsky opened at National Art Museum of Ukraine". Armenpress. 22 September 2017.

- "Exhibition dedicated to Aivazovsky's 200th birth anniversary attracts thousands of visitors within one week". panorama.am. 23 September 2017.

- "The Oligarts: How Russia's very rich are buying up the World's very best art". The Independent. 27 September 2008. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- Smale, Alison (11 August 2015). "Paradise in Russia, Plus Trouble". The New York Times.

- Moonan, Wendy (16 September 2005). "Taking Russian Art to the Motherland". The New York Times.

- Айвазовский идет на новый рекорд. Izvestia (in Russian). 30 November 2004. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- Varoli, John (14 June 2007). "Russian Sale Sets Record, 'Crazy' Prices at Christie's, London". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- "Aivazovsky Painting Sold for Record $5.2 mln". RIA Novosti. 25 April 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- Adam, Georgina (28 April 2012). "The Art Market: Munch and more". Financial Times. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- Kramer, Andrew E. (14 January 2011). "Russia: $50 Million Art and Gem Theft". The New York Times.

- Zheglov, Aleksandr (15 January 2011). "Художественный налет". Kommersant (in Russian).

- Muradyan, Tirayr (15 February 2017). ""Փյունիկ" հիմնադրամը Սերժ Սարգսյանին Այվազովսկու գողացված նկարն է նվիրել". The Armenian Times (in Armenian).

- Muradyan, Tirayr (17 February 2017). "Սերժ Սարգսյանին նվիրել են Այվազովսկու կեղծ նկարը. "Փյունիկ"-ն իր հայտարարությունը ջնջել է". The Armenian Times (in Armenian).

- "Sotheby's Removes Allegedly Stolen Russian Painting from Sale". The Moscow Times. 2 June 2015.

- Golubkova, Katya (2 June 2015). "Sotheby's withdraws sale of Russian painting alleged stolen". Reuters.

- "Aivazovsky painting, stolen in 1976, found at auction in Switzerland". TASS. 29 September 2017. Archived from the original on 7 December 2017.

Bibliography

- Newmarch, Rosa (1917). The Russian Arts. New York: E.P. Dutton & Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Adamian, A (1958). "Նոր վավերագրեր նկարիչ Հովհաննես Այվազովսկու մասին [New documentaries about the artist Hovhannes Ayvazovsky]". Bulletin of the Academy of Sciences of the Armenian SSR: Social Sciences (in Armenian). Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences (11): 89–94.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sarkssian, M. S. (1963). "Հովհաննես Այվազովսկին և հայ մշակույթը [Hovhannes Ayvazovsky and Armenian Culture]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian). Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences (4): 25–38.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Koorghinian, K. N. (1967). "Հովհաննես Այվազովսկի (Ծննդյան 150-ամյակի առթիվ) [Hovhannes Ayvazovsky]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian). Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences (2–3): 187–194.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sarkissian, M. (1967). "Հովհ. Այվազովսկու տեղը և նշանակությունը հայ նկարչության մեջ [The Place and Importance of Aivazovsky in the History of the Armenian Painting of the 19th century]". Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri (in Armenian). Armenian Academy of Sciences (10): 70–81.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harutiunian, Gr. (1965). "Հովհաննես Այվազովսկու տոհմի ծագումնաբանությունը և ազգանվան փոփոխումը [Hovhannes Aivazovsky family genealogy and family name change]". Bulletin of the Academy of Sciences of the Armenian SSR: Social Sciences (in Armenian). Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences (2): 89–94.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ghazarian, Manya (1974). "Այվազովսկի [Aivazovsky]". Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia (in Armenian). 1. Yerevan: Armenian Encyclopedia. pp. 350–351.

- Sarkissian, M. S. (1988). "Հովհաննես Այվազովսկու "Բայրոնի այցը Մխիթարյաններին Ս. Ղազար կղզում" նկարը [Hovhannes Aivazovsky's Painting "Byron's Arrival to Mekhitarists on the Island of St. Lazar".]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian). Armenian Academy of Sciences (2): 224–226. ISSN 0135-0536.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mikaelian, V. A. (1991). "И. К. Айвазовский и его соотечественники [H. K. Ayvazovsky and his compatriots]". Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri (in Russian). Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences (1): 59–70. ISSN 0320-8117.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cardwell, Richard (2005). Reception of Byron in Europe. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-6844-4. OCLC 646740691.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bolton, Roy (2010). Views of Russia & Russian Works on Paper. London: Sphinx Fine Art. ISBN 978-1-907200-05-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leek, Peter (2012). Russian Painting. Temptis. New York: Parkstone International. ISBN 978-1-85995-939-8. OCLC 795320658.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Khachatrian, Shahen. ""Поэт моря" ["The Sea Poet"]" (in Russian). Center of Spiritual Culture, Leading and National Research Samara State Aerospace University. Archived from the original on 19 March 2014.

Further reading

- books and articles on Aivazovsky

- Айвазовский И.К. Документы и материалы [I. K. Aivazovsky: Documents and Materials] (in Russian). Yerevan: Hayastan Publishing. 1967.

- Barsamov, Nikolay (1962). Иван Константинович Айвазовский, 1817—1900 [Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky, 1817-1900] (in Russian). Moscow: Iskusstvo.

- Novouspensky, Nikolai, ed. (1989). Aivazovsky. Leningrad: Aurora Art Publishers. ISBN 978-5-7300-0030-8. OCLC 21599603.

- Khachatrian, Shahen (2000). Aivazovsky: Well-Known and Unknown. Samara: Agni.

- Caffiero, Gianni; Samarine, Ivan (2000). Seas, Cities & Dreams, The Paintings of Ivan Aivazovsky. London: Alexandria Press. ISBN 1-85669-232-9.

- Bulkeley, Rip (March 2015). "Aivazovsky's Icebergs: an Antarctic mystery". Polar Record. 51 (2): 212–215. doi:10.1017/S0032247414000047.

- Lyall, Sutherland (2005). Waters of Life: The Russian Painters of Water. New Line Books. ISBN 978-1-59764-041-1.

- Tuğlacı, Pars (1983). Ayvazovski Türkiye'de (in Turkish). Istanbul: İnkılap ve Aka.

- articles analyzing Aivazovsky's works

- Yan, Zhao (2015). "Painterly Shading Ocean Surface" (Master's thesis). Texas A&M University.

- Bulkeley, Rip (2015). "Aivazovsky's Icebergs: an Antarctic mystery". Polar Record. 51 (2): 212–215. doi:10.1017/S0032247414000047.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ivan Aivazovsky. |

Galleries of Aivazovsky's paintings

- "Aivazovskiy, Ivan". at the Russian State Museum

- National Gallery of Armenia

- Russian Art Encyclopedia

- The Athenaeum

- Old Istanbul paints at Organization of Istanbul Armenians

- Ivan Aivazovsky in collection of the Odessa Art Museum. Album. Odessa, Astroprint, 2012.