Newar people

Newar (/nɪˈwɑːr/;[2] Nepal Bhasa: नेवार, endonym: Newa; Nepal Bhasa: नेवा, Pracalit script: 𑐣𑐾𑐰𑐵𑑅) or Nepami,[3] are the historical inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley and its surrounding areas in Nepal and the creators of its historic heritage and civilisation.[4] Newars form a linguistic and cultural community of primarily Indo-Aryan and Tibeto-Burman ethnicities following Hinduism and Buddhism with Newar language as their common language.[5] Newars have developed a division of labour and a sophisticated urban civilisation not seen elsewhere in the Himalayan foothills.[6] Newars have continued their age-old traditions and practices and pride themselves as the true custodians of the religion, culture and civilisation of Nepal.[7] Newars are known for their contributions to culture, art and literature, trade, agriculture and cuisine.[8] Today, they consistently rank as the most economically, politically and socially advanced community of Nepal, according to the annual Human Development Index published by UNDP.[9] Nepal's 2011 census ranks them as the nation's sixth-largest ethnicity/community, with 1,321,933 Newars throughout the country.[10]

Newar girls performing Ihi, also known as Bel Vivaah | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,321,933[1] (5% of Nepal population) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Nepal | |

| Languages | |

| Newar, Nepali | |

| Religion | |

| Hinduism and Newar Buddhism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Kirati Peoples; Maithils; Khas; other Indo-Aryan peoples; Tibeto-Burman speakers |

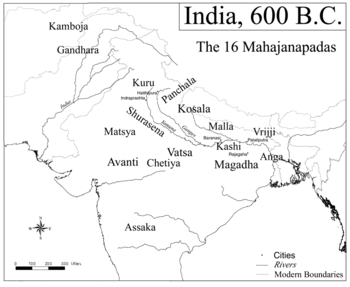

The Kathmandu Valley and surrounding territories constituted the former Newar kingdom of the Nepal Mandala.[11][12] Unlike other common-origin ethnic or caste groups of Nepal, the Newars are regarded as an example of a nation community with a relict identity, derived from an ethnically-diverse, previously-existing polity.[13] Newar community within it consists of various strands of ethnic, racial, caste and religious heterogeneity, as they are the descendants of the diverse group of people that have lived in Nepal Mandala since prehistoric times. Indo-Aryan tribes like the Licchavis, Kosala, and Mallas (N) from respective Indian Mahajanapada (i.e. Licchavis of Vajji, Kosala, and Malla (I)) that arrived at different periods eventually merged with the local population by adopting their language and customs. These tribes however retained their Vedic culture and brought with them their Sanskritic languages, social structure and Hindu religion, which was assimilated with local cultures and gave rise to the current Newar civilisation.[4] Newar rule in Nepal Mandala ended with its conquest by the Gorkha Kingdom in 1768.[14][15]

Origin of the name

The terms "Nepāl", "Newār", "Newāl" and "Nepār" are phonetically different forms of the same word, and instances of the various forms appear in texts in different times in history. Nepal is the learned (Sanskrit) form and Newar is the colloquial (Prakrit) form.[16] A Sanskrit inscription dated to 512 in Tistung, a valley to the west of Kathmandu, contains the phrase "greetings to the Nepals" indicating that the term "Nepal" was used to refer to both the country and the people.[17][18]

The term "Newar" or "Newa:" referring to "inhabitant of Nepal" appeared for the first time in an inscription dated 1654 in Kathmandu.[19] Italian Jesuit priest Ippolito Desideri (1684–1733) who traveled to Nepal in 1721 has written that the natives of Nepal are called Newars.[20] It has been suggested that "Nepal" may be a sanskritization of "Newar", or "Newar" may be a later form of "Nepal".[21] According to another explanation, the words "Newar" and "Newari" are colloquial forms arising from the mutation of P to W, and L to R.[22]

As a result of the phonological process of dropping the last consonant and lengthening the vowel, "Newā" for Newār or Newāl, and "Nepā" for Nepāl are used in ordinary speech.[23][24]

History

For about a thousand years, the Newar civilization in Central Nepal preserved a microcosm of classical North Indian culture in which Brahmanic and Buddhist elements enjoyed equal status.[25] Snellgrove and Richardson (1968) speak of 'the direct heritage of pre-Islamic India'. The Malla dynasty was noted for their patronisation of the Maithili language (the language of the Mithila region) which was afforded an equal status to that of Sanskrit in the Malla court.[26] Maithil Brahmin priests were invited to Kathmandu and many Maithil families settled in Kathmandu during Malla rule.[27] Due to influx of people from both north (Tibet) and south (Bihar) who brought with them not only their genetic and racial diversity but also greatly moulded the dominant culture and tradition of Newars.

The different divisions of Newars had different historical developments. The common identity of Newar was formed in the Kathmandu Valley. Until the conquest of the valley by the Gorkha Kingdom in 1769,[28] all the people who had inhabited the valley at any point of time were either Newar or progenitors of Newar. So, the history of Newar correlates to the history of the Kathmandu Valley (or Nepala Mandala) prior to the establishment of the modern state of Nepal.

The earliest known history of Newar and the Kathmandu Valley blends with mythology recorded in historical chronicles. One such text, which recounts the creation of the valley, is the Swayambhu Purana. According to this Buddhist scripture, the Kathmandu Valley was a giant lake until the Bodhisattva Manjusri, with the aid of a holy sword, cut a gap in the surrounding hills and let the water out.[29] This apocryphal legend is supported by geological evidence of an ancient lakebed, and it provides an explanation for the high fertility of the Kathmandu Valley soil.[30]

According to the Swayambhu Purana, Manjusri then established a city called Manjupattan (Sanskrit "Land Established by Manjusri"), now called Manjipā, and made Dharmākara its king.[31] A shrine dedicated to Manjusri is still present in Majipā. No historical documents have been found after this era till the advent of the Gopal era. A genealogy of kings is recorded in a chronicle called Gopalarajavamsavali.[32] According to this manuscript, the Gopal kings were followed by the Mahispals and the Kirats before the Licchavis entered from the south. Some claim Buddha to have visited Nepal during the reign of Kirat King Jitedasti.[33] Newar reign over the valley and their sovereignty and influence over neighboring territories ended with the conquest of the Kathmandu Valley in 1769 by the Gorkhali Shah dynasty founded by Prithvi Narayan Shah.[28][34]

Prior to the Gorkha conquest, which began with the Battle of Kirtipur in 1767, the borders of Nepal Mandala extended to Tibet in the north, the nation of the Kirata in the east, the kingdom of Makwanpur in the south[35] and the Trishuli River in the west which separated it from the kingdom of Gorkha.[36]

Economic history

Trade, industry and agriculture have been the mainstay of the economy of the Newars. They are made up of social groups associated with hereditary professions that provide ritual and economic services. Merchants, craftsmen, artists, potters, weavers, dyers, farmers and other castes all played their part in creating a flourishing economic system. Elaborate cultural traditions which required the use of varied objects and services also fueled the economy. Towns and villages in the Kathmandu Valley specialized in producing particular products, and rich agriculture produced a surplus for export.

For centuries, Newar merchants have handled trade between Tibet and India Besides exporting locally manufactured products to Tibet. Rice was another major export. Porters and pack mules transported merchandise over mountain tracks that formed the old trade routes. Since the 18th century, Newars have spread out across Nepal and established trading towns dotting the mid hills. They are known as jewelry makers and shopkeepers. Today, they are engaged in modern industry, business and service sectors.[37][38]

Castes and communities

Newars forms an ethnolinguistic community distinct from all the other ethnic groups of Nepal. Newars are divided into various endogamous clans or groups on the basis of their ancient hereditary occupations, deriving its roots in the classic late-Vedic Varna model. Although first introduced in the time of the Licchavis, the present Newar caste system assumed its present shape during the medieval Malla period.

- Artisan castes: "Ritually pure" occupational castes (Sat-Shudra): Balami (field workers and farmers), Bha/Karanjit (death ritual specialists), Chipā/Ranjitkar (dyers), Duhim/Putwar/Dali (carriers), Gathu/Mālākār/Mali (gardeners), Khusa/Tandukar (palanquin bearers/farmers), Pahari/Nagarkoti (farmers from Valley outskirts), Kau/Nakarmī (blacksmiths), Nau/Napit (barbers), Puñ/Chitrakar (painters), Sayami/Mānandhar (oilpressers), etc.

- Shakya: Descendants of Lord Buddha, Buddhist temple priests and also traditionally goldsmiths.

- Brahmin: The two main groups are: Rajopadhyaya (Dyabhāju Brāhman or Bājyé) who are purohits for Hindu Newars, and Maithil Brahmin (Jhā Bajé) who are temple priests of Kathmandu's various Hindu shrines.

- Chyamé/Chamaha: Traditionally fishermen, sweepers. A Scheduled Caste.

- Dhobi: Traditionally washermen. A Scheduled Caste.

- Dyahla/Podé: Traditionally temple cleaners, fishermen, sweepers. A Scheduled Caste.

- Gubhāju/Bajracharya: Buddhist purohits and temple priests of Kathmandu's various Buddhist shrines.

- Jyapu: Traditionally farmers; majority of Newar population inside Kathmandu Valley. Also includes Suwāl, Basukala, etc. (Bhaktapur Hindu Jyapus), Kumhā/Prajapati (potterers and clay workers), Awalé (brickmakers), Sāpu (descendants of Gopāl dynasty), etc.

- Jogi/Kapali (Newar caste): A caste associated as being descendants of the Kanphata Yogi sect. Also traditionally tailors, musicians. Previously, a Scheduled Caste.

- Chathariya Srēṣṭha: Kshatriya aristocratic bloc which includes Malla descendants, their numerous Hindu courtier clans (Pradhan, Pradhananga, Maskay, Hada, Amātya, Mathema, etc.) and Kshatriya-status specialists like Joshi (astrologers), Vaidya (Ayurvedic practitioners), Rajbhandārī (treasurers), Karmāchārya (Tantric priests), Kayastha (scribes), among others.

- Kulu/Dom: Traditionally leather workers. A Scheduled Caste.

- Nayé/Khadgi/Shahi: Traditionally butchers and musicians. Previously a Scheduled Caste.

- Panchthariya Srēṣṭha: Chief Hindu trader and merchant group including Shrestha (administrators and traders).

- Rajkarnikar or Halwai: Traditional confectioners and sweetmakers. Kathmandu Halwais are Buddhist, whereas Lalitpur Halwais are Hindu.

- Shilpakar: Wood carvers.

- Tamrakar: Trader and merchant group from Lalitpur; traditionally involved as coppersmiths.

- Urāya/Udās: Chief Buddhist trader, merchant and artisan group including Tuladhar and Bania (merchants), Kansakar (bronzesmiths), Sthapit, Kasthakar (architects/carpenters), etc.

Religion

According to the 2011 Nepal Census, 87.38% of the Newars were Hindu and 10.74% were Buddhist.[39]

Out of the three main cities of the Kathmandu Valley which are historically Newar, the city of Patan is the most Buddhist containing the four stupas built by Indian emperor Ashoka. Bhaktapur is primarily Hindu, while Kathmandu is a mix of both. Generally, both Hindu and Buddhist deities are worshiped and festivals are celebrated by both religious groups. However, for ritual activities, Hindu and Buddhist Newars have their own priests (Rajopadhyaya Brahmins for Hindus and Vajracharyas for Buddhists) and varying amounts of cultural differences.

Religiously, the Newars can be classified as both Hindu and Buddhist. The major cults are Vajrayana Buddhism and Tantric Hinduism. The former is referred to as Buddhamarga, the latter as Sivamarga. Both creeds have been established since antiquity in the valley. Both Buddhamargi and Sivamargi Newars are Tantricists, Within the Newar community, many different esoteric Tantric cults of Buddhist, Shaiva, and Vaishnava denominationd are practiced.[40] In this regard, cults of the Mother Goddesses and their consorts, the Bhairavas, are particularly important.

The most important shrines in the Valley are Swayambhunath (Buddhist) and Pashupatinath (Hindu). Different castes worship different deities at different occasions, and more or less intensively. Only the higher echelons in the caste system claim to be exclusively Buddhist or Hindu. The Vajracharyas, Buddhist priests, will adamantly maintain that they are Buddhists, and so will the Bare (Shakya) and the Uray (Tuladhars, et al.), whereas, the Dyabhāju Brāhman, the Jha Brāhman, and the dominant Shresthas will maintain that they are Hindus. Further down in the caste hierarchy no distinction is made between Buddhists and Hindus. Hindu and Buddhist alike always worship Ganesh first in every ritual, and every locality has its local Ganesh shrine (Ganesh Than).[41]

Although Newar Buddhism (Vajrayana) had been traditionally practiced in the Kathmandu Valley,[42] Theravada Buddhism made a comeback in Nepal in the 1920s and now is a common form of Buddhism among Buddhamargi Newars.[43][44]

Language

"Nepal Bhasa" is classified as among the Sino-Tibetan languages but it has greatly derived much of its grammar, words and lexicon from the influences of southern Indo-Aryan languages like Sanskrit, Prakrit, and Maithili. Newars are bound together by a common language and culture.[45] Their common language is Nepal Bhasa or the linguistic progenitor of that language. Nepal Bhasa is the term recognised by the government.[46]

Nepal Bhasa already existed as a spoken language during the Licchavi period and is believed to have developed from the language spoken in Nepal during the Kirati period.[47] Inscriptions in Nepal Bhasa emerged from the 12th century, the palm-leaf manuscript from Uku Bahah being the first example.[48] Nepal Bhasa developed from the 14th to the late 18th centuries as the court and state language.[49] It was used universally in stone and copper inscriptions, sacred manuscripts, official documents, journals, title deeds, correspondence and creative writing.

In 2011, there were approximately 846,000 native speakers of Nepal Bhasa.[50] Many Newar communities within Nepal also speak their own dialects of Nepal Bhasa, such as the Dolakha Newar Language.[51] Nepal Bhasa is of Tibeto-Burman origin but has been heavily influenced by Indo-Aryan languages like Sanskrit, Pali, Bengali and Maithili.

Scripts

Nepal Bhasa script is a group of scripts that developed from the Brahmi script and are used primarily to write Nepal Bhasa and Sanskrit. Among the different scripts, Ranjana, Bhujinmol, and Prachalit are the most common. Nepal script is also known as Nepal Lipi and Nepal Akhala.[52]

Nepal Bhasa scripts appeared in the 10th century. For a thousand years, it was used on stone and copper plate inscriptions, coins (Nepalese mohar), palm-leaf documents and Hindu and Buddhist manuscripts. Devanagari began to be used to write Nepal Bhasa in the beginning of the 20th century, and Nepal script has limited usage today.[53]

Literature

Nepal Bhasa is one of the five languages in the Sino-Tibetan family with an ancient literary tradition. Literature in Nepal Bhasa began as translation and commentary in prose in the 14th century AD.[54] The earliest known document in Nepal Bhasa is called "The Palmleaf from Uku Bahal" which dates from 1114 AD during the Thakuri period.[55]

Classical Nepal Bhasa literature is represented by all the three major genres—prose, poetry, and drama. Most of the writings consist of prose including chronicles, popular stories and scientific manuals. Poetry consists of love songs, ballads, work songs, and religious poetry. The earliest poems date from the 1570s. Epic poetry describing historical events and tragedies are very popular. The ballads Sitala Maju, about the expulsion of children from Kathmandu, Silu, about an ill-fated pilgrimage to Gosaikunda, and Ji Waya La Lachhi Maduni, about a luckless Tibet trader, are sung as seasonal songs.

The dramas are based on stories from the epics, and almost all of them were written during the 17th and 18th centuries.[56] Nepal Bhasa literature flourished for five centuries until 1850.[57] Since then, it suffered a period of decline due to political oppression. The period 1909–1941 is known as the Nepal Bhasa renaissance period when writers defied official censure and braved imprisonment to create literary works. Modern Nepal Bhasa literature began in the 1940s with the emergence of new genres like short stories, poems, essays, novels and plays.[58]

Politics

Newa Autonomous State

Newa Autonomous State is a proposed federal state of Nepal which establishes the historical native homeland of Newa people as a federal state.[59][60] The historical territories of Newars is called Nepal Mandala. The Newa Autonomous State mandates to reconstruct the district division and create an autonomous Newa province. It includes historically Newa residing settlements and Newa dominant zones of Kathmandu, Bhaktapur, Lalitpur, Newa towns of Dolakha, Newa settlements of Nuwakot, Newa settlements of Makwanpur, Newa settlements of Ramechhap, Newa settlements of Sindupalchok, Newa settlements of Kavre West.[61][62][63]

Dance

Masked dance

The Newar dance consists of sacred masked dance,[64] religious dance without the use of masks known as Dyah Pyakhan, dance performed as part of a ritual and meditation practice known as Chachaa Pyakhan (Nepal Bhasa: चचा प्याखं) (Charya Nritya in Sanskrit)[65] and folk dance. There are also masked dance dramas known as Daboo Pyakhan which enact religious stories to the accompaniment of music.

Dhime dance

The dance done in the tune of Dhime are Dhime dance.

Music

Traditional Newa music consists of sacred music, devotional songs, seasonal songs, ballads and folk songs.[66] One of the most well-known seasonal songs is Sitala Maju. The ballad describes the expulsion of children from Kathmandu in the early 19th century. Another seasonal song Silu is about a pilgrimage to Gosaikunda that went wrong. Ji Waya La Lachhi Maduni is a tragedy song about a newly married couple. The ballad Rajamati about unlucky lovers is widely popular. In 1908, maestro Seturam Shrestha made the first recording of the song on gramophone disc in Kolkata.

Common percussion instruments consist of the dhimay,[67] khin, naykhin and dhaa. Wind instruments include the bansuri (flute), payntah (long trumpet) and mwahali (short trumpet), chhusya, bhusya, taa (cymbals), and gongs are other popular instruments. String instruments are very rare. Newa people call their music Dhime Baja.

The musical style and musical instruments are still in use today. Musical bands accompany religious processions in which an idol of a deity is placed in a chariot or portable shrine and taken around the city. Devotional songs are known as bhajan may be sung daily in community houses. Hymn societies like Gyanmala Bhajan Khala hold regular recitals. Dapa songs are sung during hymn singing seasons at Temple squares and sacred courtyards.

Gunla Bajan musical bands parade through the streets during Gunla, the 10th month of the Nepal Sambat calendar which is a holy month for Newar Buddhists.[68] Musical performances start with an overture which is a salutation to the gods.

Seasonal songs and ballads are associated with particular seasons and festivals. Music is also played during wedding processions, life-cycle ceremonies and funeral processions.[69]

Popular traditional songs

- Ghātu (summer music, this seasonal melody is played during Pahan Charhe festival)

- Ji Wayā Lā Lachhi Maduni (tragedy of a merchant)

- Mohani (festive joy, this seasonal tune is played during Mohani festival)

- Rājamati (about young lovers)

- Silu (about a couple who get separated during a pilgrimage, this seasonal music is played during the monsoon)

- Sitālā Māju (lament for children expelled from the Kathmandu Valley)

- Swey Dhaka Swaigu Makhu (song about love)

- Holi ya Mela (About theholi.)

- Wala Wala Pulu Kishi (Sung in Indra jatra)

- Yo Sing Tyo

- Yomari Maku

- Dhanga maru ni bhamcha (song to complain laziness of daughter in law by man's father.)

Religious music

- Gunlā Bājan

- Malshree dhun

- Dapha Bhajan

- Mye kasa

Art

The Newars are the creators of most examples of art and architecture in Nepal.[70] Traditional Newar art is basically religious art. Newar devotional paubha painting, sculpture and metal craftsmanship are world-renowned for their exquisite beauty.[71] The earliest dated paubha discovered so far is Vasudhara Mandala which was painted in 1365 AD (Nepal Sambat 485).[72] The murals on the walls of two 15th-century monasteries in the former kingdom of Mustang in the Nepal Himalaya provide illustrations of Newar works outside the Kathmandu Valley.[73] Stone sculpture, wood carving, repoussé art and metal statues of Buddhist and Hindu deities made by the lost-wax casting process[74] are specimens of Newar artistry.[75] The Peacock Window of Bhaktapur and Desay Madu Jhya of Kathmandu are known for their wood carving.

Building elements like the carved Newar window, roof struts on temples and the tympanum of temples and shrine houses exhibit traditional creativity. From as early as the seventh century, visitors have noted the skill of Newar artists and craftsmen who left their influence on the art of Tibet and China.[76] Newars introduced the lost-wax technique into Bhutan and they were commissioned to paint murals on the walls of monasteries there.[77][78] Sandpainting of mandala made during festivals and death rituals is another specialty of Newar art.

Besides exhibiting a high level of skill in the traditional religious art, Newar artists have been at the forefront of introducing Western art styles in Nepal. Raj Man Singh Chitrakar (1797-1865) is credited with starting watercolor painting in the country. Bhaju Man Chitrakar (1817–1874), Tej Bahadur Chitrakar (1898-1971) and Chandra Man Singh Maskey were other pioneer artists who introduced modern style paintings incorporating concepts of lighting and perspective.[79]

Architecture

There are seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites and 2,500 temples and shrines in the Kathmandu Valley that illustrate the skill and aesthetic sense of Newar artisans. Fine brickwork and woodcarving are the marks of Newar architecture.[80] Residential houses, monastic courtyards known as baha and bahi, rest houses, temples, stupas, priest houses and palaces are the various architectural structures found in the valley. Most of the chief monuments are located in the Durbar Squares of Kathmandu, Lalitpur and Bhaktapur, the old royal palace complexes built between the 12th and 18th centuries.[81]

Newa architecture consists of the pagoda, stupa, shikhara, chaitya and other styles. The valley's trademark is the multiple-roofed pagoda which may have originated in this area and spread to India, China, Indochina and Japan.[82][83] The most famous artisan who influenced stylistic developments in China and Tibet was Arniko, a Newar youth who traveled to the court of Kublai Khan in the 13th century AD.[82] He is known for building the white stupa at the Miaoying Temple in Beijing.

Settlements

Durbar squares, temple squares, sacred courtyards, stupas, open-air shrines, dance platforms, sunken water fountains, public rest houses, bazaars, multistoried houses with elaborately carved windows and compact streets are the characteristics of traditional planning. Besides the historical cities of Kathmandu, Lalitpur, Bhaktapur, Madhyapur Thimi, Chovar, Bungamati, Thankot and Kirtipur, small towns with a similar artistic heritage dot the Kathmandu Valley where almost half of the Newar population lives.[84]

Outside the valley, historical Newar settlements include Nuwakot,[85] Nala, Banepa, Dhulikhel, Panauti, Dolakha, Chitlang and Bhimphedi.[86] The Newars of Kathmandu founded Pokhara in 1752 at the invitation of the rulers of Kaski.[87] Over the last two centuries, Newars have fanned out of the Kathmandu Valley and established trade centers and settled in various parts of Nepal. Bandipur, Baglung, Silgadhi and Tansen in west Nepal and Chainpur and Bhojpur in east Nepal contain large Newar populations.

Outside Nepal, many Newars have settled in Darjeeling and Kalimpong[88] in West Bengal, Assam, Manipur and Sikkim, India.[89] Newars have also settled in Bhutan. Colonies of expatriate Newar merchants and artisans existed in Lhasa, Shigatse and Gyantse in Tibet till the mid-1960s when the traditional trade came to an end after the Sino-Indian War.[90] In recent times, Newars have moved to different parts of Asia, Europe and America.[91][92][93]

Festivals

Newar religious culture is rich in ceremony and is marked by frequent festivals throughout the year.[94] Many festivals are tied to Hindu and Buddhist holidays and the harvest cycle. Street celebrations include pageants, jatras or processions in which a car or portable shrine is paraded through the streets and sacred masked dances. Other festivals are marked by family feasts and worship. The celebrations are held according to the lunar calendar, so the dates are changeable.

Mohani (Dasain) is one of the greatest annual celebrations which is observed for several days with feasts, religious services, and processions. During Swanti (Tihar), Newars celebrate New Year's Day of Nepal Sambat by doing Mha Puja, a ritual in which a mandala is worshipped, that purifies and strengthens one spiritually for the coming year. Similarly, Bhai Tika is also done during Swanti. It is a ritual observed to worship and respect a woman's brothers, with or without blood relation. Another major festival is Sā Pāru when people who have lost a family member in the past year dress up as cows and saints, and parade through town, following a specific route. In some cases, a real cow may also be a part of the parade. People give such participants money, food and other gifts as a donation. Usually, children are the participants of the parade.

In Kathmandu, the biggest street festival is Yenya (Indra Jatra) when three cars bearing the living goddess Kumari and two other child gods are pulled through the streets and masked dance performances are held. The two godchildren are Ganesh and Bhairav. Another major celebration is Pahan Charhe when portable shrines bearing images of mother goddesses are paraded through Kathmandu. During the festival of Jana Baha Dyah Jatra, a temple car with an image of Karunamaya is drawn through central Kathmandu for three days. A similar procession is held in Lalitpur known as Bunga Dyah Jatra[95] which continues for a month and climaxes with Bhoto Jatra, the display of the sacred vest.[96] The biggest outdoor celebration in Bhaktapur is Biska Jatra (Bisket Jatra) which is marked by chariot processions and lasts for nine days.[97] Sithi Nakha is another big festival when worship is offered and natural water sources are cleaned.[98] In addition, all Newar towns and villages have their particular festival which is celebrated by holding a chariot or palanquin procession.

Paanch Chare is one of the many occasions or festivals celebrated by the Newa community, natives from Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. This is celebrated on the Chaturdasi (Pisach Chaturdashi) day according to new lunar calendar on the month of Chaitra.

Clothing

Western wear is the norm as in urban areas in the rest of the country. Traditionally men wear tapuli (cap), long shirt (tapālan) and trousers (suruwā), also called Daura-Suruwal. Woman wear cheeparsi (sari) and gaa (long length shawl) while younger girls wear ankle-length gowns (bhāntānlan). Ritual dresses consist of pleated gowns, coats and a variety of headresses. Jyapu women have a distinctive sari called Hāku Patāsi which is a black sari with distinctive red border. Jyapu men also have a distinctive version of the tapālan suruwā. Similarly, a shawl (gā) is worn by men and women. Traditionally, Newar women wear a shoe made out of red cloth, Kapa lakaan. It is decorated with glitters and colorful beads (potya). One of the major parts of Newar dress ups is bracelets (chūra) and mala(necklaces).

Cuisine

Meals can be classified into three main categories: the daily meal, the afternoon snack and festival food. The daily meal consists of boiled rice, lentil soup, vegetable curry and relish. Meat is also served. The snack generally consists of rice flakes, roasted and curried soybeans, curried potato and roasted meat mixed with spices.

Food is also an important part of the ritual and religious life of the Newars, and the dishes served during festivals and feasts have symbolic significance.[99] Different sets of ritual dishes are placed in a circle around the staple Bawji (rice flakes or Flattened) to represent and honour different sets of deities depending on the festival or life-cycle ceremony.[100]

Kwāti (क्वाति soup of different beans), kachilā (कचिला spiced minced meat), chhoyalā (छोयला water buffalo meat marinated in spices and grilled over the flames of dried wheat stalks), pukālā (पुकाला fried meat), wo (वः lentil cake), paun kwā (पाउँक्वा sour soup), swan pukā (स्वँपुका stuffed lungs), syen (स्येँ fried liver), mye (म्ये boiled and fried tongue), sapu mhichā (सःपू म्हिचा leaf tripe stuffed with bone marrow), sanyā khunā (सन्या खुना jellied fish soup) and takhā (तःखा jellied meat) are some of the popular festival foods. Dessert consists of dhau (धौ yogurt), sisābusā (सिसाबुसा fruits) and mari (मरि sweets). Thwon (थ्वँ rice beer) and aylā (अयला local alcohol) are the common alcoholic liquors that Newars make at home.

Traditionally, at meals, festivals and gatherings, Newars sit on long mats in rows. Typically, the sitting arrangement is hierarchical with the eldest sitting at the top and the youngest at the end. Newar cuisine makes use of mustard oil and a host of spices such as cumin, sesame seeds, turmeric, garlic, ginger, mint, bay leaves, cloves, cinnamon, pepper, chilli and mustard seeds. Food is served in laptya (लप्त्य plates made of special leaves, held together by sticks). Similarly, any soups are served in botā (बोटा bowls made of leaves). Liquors are served in Salinchā (सलिंचाः bowls made of clay) and Kholchā (खोल्चाः small metal bowls).

Newar people are much innovative in terms of cuisine. They have a tradition to prepare various foods according to the festivals. Some of the popular cuisines that are prepared with the festivals are:

Life-cycle ceremonies

Elaborate ceremonies chronicle the life cycle of a Newar from birth till death.[101][102] Newars consider life-cycle rituals as a preparation for death and the life after it. Hindus and Buddhists alike perform the "Sorha Sanskaar Karma" or the 16 sacred rites of passage, unavoidable in a Hindu person's life. The 16 rites have been shortened to 10 and called "10 Karma Sanskar" (Nepal Bhasa: दश कर्म संस्कार). These include important events of a person's life like "Jatakarma" (Nepal Bhasa: जातकर्म) (Childbirth), "Namakaran" (Nepal Bhasa: नामकरण) (Naming the child), "Annapraasan" (Nepal Bhasa: अन्नप्राशन) (First rice feeding ceremony), "Chudakarma" or "Kaeta Puja" (first hair shaving and loin cloth ceremony), "Vivaaha" (Nepal Bhasa: विवाह) (Wedding), among others.

- Chudakarma ceremony and (Bare Chuyegu/Acharyabhisheka or Bratabandha/Upanayana)

Once such important rite of passage ceremony among the male Newars is performing the loin-cloth and head-shaving ceremony called Chudākarma (Nepal Bhasa: चुडाकर्म) or Kaeta Puja (Nepal Bhasa: काएत पूजा) which is traditionally performed for boys aged five to thirteen according to the religious affiliation Newars identify with.[103]

In this ceremony, Buddhist Newars - Gubhāju-Baré (Bajracharya-Shakya), Urāy, Jyapu and few artisan castes like Chitrakār - perform their Pravrajyā (Sanskrit: प्रवराज्या) ceremony by mimicking Gautama Buddha's ascetic and medicant lifestyle and the steps to attain monkhood and nirvana where the boy stays in a Buddhist monastery, Vihara, for three days, living the life of a monk and abandoning all material pleasures. On the fourth day, he disrobes and returns to his family and henceforth becomes a householder Buddhist for the rest of his life.[104] The Buddhist priestly clan Gubhāju-Baré (Bajracharya and Shakya) go through an additional initiation ceremony called Bare Chuyegu (becoming a Baré) while Bajracharya boys are further required to go through Acharyabhisheka (Sanskrit: आचार्याभिषेक) which is a Tantric initiation rite that qualifies a Bajracharya to perform as a purohita.[105]

Hindu Newars perform the male initiation ceremony as a ritual observance of the brahmachārya - the first stage in the traditional four stages of life. During the ritual, the young boy renounces family and lineage for the celibate religious life. His head is fully shaved except a tuft in the top, he must don yellow/orange robes of the mendicant, he must beg rice from his relatives and prepare to wander out into the world. Having this symbolically fulfilled the ascetic ideal, he can be called back by his family to assume the life of a householder and his eventual duty as a husband and a father. Twice-born (Brahmin and Kshatriya) Newars - Rajopādhyāyas and Chatharīyas - additionally perform the Upanayana initiation where the boy receives his sacred thread (Sanskrit: यज्ञोपवीत) and the secret Vedic mantras - RV.3.62.10 (Gāyatrī mantra) for Brahmins and RV.1.35.2 (Shiva mantra) for Chatharīyas.[106] The boy is then fully inducted into his caste status as a Dvija with the obligation to observe henceforth all commensal rules and other caste obligations(Nepal Bhasa: कर्म चलेको).[104]

- Macha Janku

This is the rice feeding ceremony, "Annapraasan" (Nepal Bhasa: अन्नप्राशन). It is performed at the age of six or eight months for boys and at the age of five or seven months for girls.

For a female child, Ihi (Ehee)(Nepal Bhasa: ईहि) short for Ihipaa (Eheepā)(Nepal Bhasa: ईहिपा) (Marriage) is performed between the ages of five to nine. It is a ceremony in which pre-adolescent girls are "married" to the bael fruit (wood apple), which is a symbol of the god Vishnu. It is believed that if the girl's husband dies later in her life, she is not considered a widow because she is married to Vishnu, and so already has a husband that is believed to be still alive.

- Bahra

Girls have yet another ceremonial ritual called Bahra Chuyegu(Nepal Bhasa: बराह चुयेगु) when a girl approaches puberty. This is done in her odd number year like 7,9 or 11 before mensuration. She is kept in a room for 12 days hidden and is ceremonially married to the sun god Surya.

Jankwa or Janku is an old-age ceremony which is conducted when a person reaches the age of 77 years, seven months, seven days, seven hours, seven minutes, seven-quarter.[43] Three further Janku ceremonies are performed at similar auspicious milestones at age 83, 88 and 99. The first Janwa is called "Bhimratharohan", the second "Chandraratharohan", the third "Devaratharohan", and the fourth "Divyaratharohan". After the second Jankwa, the person is accorded deified status.

- Vivaaha (Wedding)

The next ceremony common to both boys and girls is marriage and the rituals performed are similar to most normal Hindui marriages. The Newar custom, similar to that of Hindus, is that the bride almost always leaves home at marriage and moves into her husband's home and adopts her husband's family name as her own. Cross-cousin and parallel-cousin marriage is forbidden. Marriage is usually arranged by parents who use a gobetween(lamee). Marriage by elopement is popular in some peripheral villages.

- The Sagan ceremony where auspicious food items are presented is an important part of life-cycle rituals.

- All Newars, except the Laakumi and Jogi caste, cremate their dead. The Jogis bury their dead. As part of the funeral, offerings are made to the spirit of the deceased, the crow and the dog. The crow and the dog represent ancestors and the god of death. Subsequently, offerings and rituals are conducted four, seven, eight, 13 and 45 days following death and monthly for a year and then annually.[103]

- Buddhist Newars also make a mandala (sand painting) depicting the Buddha on the third day after death which is preserved for four days.

Newa Games

The games which had been played by prasanga people from their ancient time can be classified as Newa games.

Kana kana pichha (Blindfold game), Piyah (a game played with stone by pushing stone within the marks drawn in the ground), Gatti ( another game played with stone by hand), pasa are some games played by Newar people since ancient time.

Notable Newar People

- Sankhadhar Sakhwa (879 AD) philanthropist, related to Nepal Sambat

- Shukra Raj Shastri (1894-1941), Freedom Fighter, Martyr

- Gangalal Shrestha (1919-1941), Freedom Fighter, Martyr

- Dharma Bhakta Mathema (1908-1941), Freedom Fighter, Martyr

- Ganesh Man Singh (1915-1997) Freedom Fighter, Leader

- Pushpa Lal Shrestha (1924-1978), Founder of Communist Party of Nepal

- Marich Man Singh Shrestha (1942-2013) Ex. Prime Minister

- Sahana Pradhan (1927-2014), Leader of CPN-ML, Ex. Deputy PM

- Baikuntha Manandhar (b. 1952), Fastest Runner who competed at four consecutive Olympic Games, from 1976 to 1988.

- Siddhicharan Shrestha (1912-1992), Poet, aka Yug Kavi

- Chittadhar Hridaya (19 May 1906 – 9 June 1982), Poet, aka Kavi Keshari

- Satya Mohan Joshi (b.1920), Scholar of history and culture

- Narayan Gopal (1939-1990), Singer, aka Swar Samrat

- Pashupati Bhakta Maharjan, Chief secretary of King Birendra and King Gyanendra of Nepal

- Tara Devi (1945-2006), Singer, aka Swar Samragi

- Kashiraj Pradhan (b.1905), Pro democracy leader in erstwhile Kingdom of Sikkim

- Phatteman Rajbhandari, Singer

- Nahakul Pradhan, pro democracy leader in erstwhile kingdom of Sikkim

- Prem Dhoj Pradhan (b.1938), Singer

- Ganga Prasad Pradhan, main translator of Nepali Bible

- Madan Krishna Shrestha (b.1950), Actor

- Shiv Shrestha, Actor

- Kumar Pradhan, Historian

- Shree Krishna Shrestha, (19 April 1967 – 10 August 2014), Actor

- Durga Lal Shrestha, (b. July 1937), poet of Nepal Bhasa and Nepali

- Poornima Shrestha, (b. 6 September 1960), Bollywood film playback singer

- Narayan Man Bijukchhe, (b. 9 March 1939), writer, Member of the Legislature Parliament of Nepal

- Binod Pradhan, Bollywood cinematographer

- Adrian Pradhan, Vocalist

- Namrata Shrestha, famous Nepali actress

- Karna Shakya, environmentalist, conservationist, hotel entrepreneur, writer and philanthropist

- Tara Bir Singh Tuladhar, artist and composer on the classical string instrument Sitar

- Aashirman DS Joshi, Actor

- Ayushman Joshi, Actor

- Sanju Pradhan, Footballer

- Jharana Bajracharya - Miss Nepal 1997

- Usha Khadgi - Miss Nepal 2000

- Payal Shakya - Miss Nepal 2004

- Sadichha Shrestha,(b. 23 November 1991), Miss Nepal World 2010

- Sahana Bajracharya - Miss Nepal Earth 2010 | Model| Actress | Media Personality

- Malina Joshi - Miss Nepal World 2011

- Sarina Maskey - Miss Nepal International 2011

- Shristi Shrestha - Miss Nepal World 2012 & Miss World 2012-Top 20 finalist

- Nagma Shrestha - Miss Nepal Earth 2012 | Miss Nepal Universe 2017

- Ishani Shrestha - Miss Nepal World 2013 & Miss World 2013- Beauty With A Purpose | Top 10 finalist

- Prinsha Shrestha - Miss Nepal Earth 2014

- Sonie Rajbhandari - Miss Nepal International 2014

- Evana Manandhar - Miss Nepal 2015

- Asmi Shrestha - Miss Nepal 2016

- Ronali Amatya - Miss Nepal International 2018

- Anushka Shrestha - Miss Nepal World 2019 & Miss World 2019- Beauty With A Purpose | Miss Multimedia | Top 12 finalist

- Meera Kakshapati - Miss Nepal International 2019

- Nitesh R Pradhan - Journalist & singer

- Ashish Pradhan - Footballer

Gallery

Statue in Lalitpur

Statue in Lalitpur The world-famous Golden Gate of Bhaktapur

The world-famous Golden Gate of Bhaktapur

See also

- Lhasa Newar (trans-Himalayan traders)

- Newa Rastriya Mukti Morcha, Nepal

References

- Sharma, Man Mohan (1978). Census of Nepal, 2011.

- "Newar". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- (Mrigendra Lal Singh. Nepami: An Idol of Yalambar. 2016)

- von Furer-Haimendorf, Christoph (1956). "Elements of Newar Social Structure". Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 86 (2): 15–38. doi:10.2307/2843991. JSTOR 2843991. Page 15.

- Levy, Robert I. (1991). "Nepal, the Kathmandu Valley, and Some History". Mesocosm: Hinduism and the Organization of a Traditional Newar City in Nepal. University of California Press. p. 34. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- Gellner, David N. (1986). "Language, Caste, Religion and Territory: Newar Identity Ancient and Modern". European Journal of Sociology. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- Tree, Isabella. "Living Goddesses of Nepal". nationalgeographic.com. National Geographic.

- Lieberman, Marcia R. (9 April 1995). "The Artistry of the Newars". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- Nepal Human Development Report 2014 Beyond Geography, Unlocking Human Potential. Kathmandu, Nepal: Government of Nepal National Planning Commission. 2014. ISBN 978-9937-8874-0-3.

- "Major highlights" (PDF). Central Bureau of Statistics. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2013. Page 4.

- Slusser, Mary (1982). Nepal Mandala: A Cultural Study of the Kathmandu Valley. Princeton University. ISBN 978-0-691-03128-6. Page vii.

- Lawoti, Mahendra (2007). Contentious Politics and Democratization in Nepal. SAGE Publications India. p. 247. ISBN 978-8132101543.

- Granthavali-v-1-11(pb) vol-5, Hazari Prasad khè", Rajkamal Prakashan Pvt Ltd, 1 January 2007, p.279

- Waller, Derek J. (2004). The Pundits: British Exploration Of Tibet And Central Asia. University Press of Kentucky. p. 171. ISBN 978-0813191003.

- Lewis, Todd T.; Tuladhar, Subarna Man (2009). Sugata Saurabha An Epic Poem from Nepal on the Life of the Buddha by Chittadhar Hridaya. Oxford University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0199712014.

- Malla, Kamal P. "Nepala: Archaeology of the Word" (PDF). Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2011. Page 7.

- Malla, Kamal P. "Nepala: Archaeology of the Word" (PDF). Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2011. Page 1.

- Majupuria, Trilok Chandra; Majupuria, Indra (1979). Glimpses of Nepal. Maha Devi. p. 8. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- "The Newars". Archived from the original on 17 April 2015. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- Desideri, Ippolito and Sweet, Michael Jay (2010). Mission to Tibet: The Extraordinary Eighteenth-Century Account of Father Ippolito Desideri, S.J.. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 978-0861716760. Page 463.

- Turner, Ralph L. (1931). "A Comparative and Etymological Dictionary of the Nepali Language". London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. Archived from the original on 14 July 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2011. Page 353.

- Hodgson, Brian H. (1874). "Essays on the Languages, Literature and Religion of Nepal and Tibet". London: Trübner & Co. Retrieved 8 May 2011. Page 51.

- Shakya, Daya R. (1998–1999). "In Naming a Language" (PDF). Newāh Vijñāna. Portland, Oregon: International Newah Bhasha Sevā Samiti (2): 40. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- Joshi, Sundar Krishna (2003). Nepal Bhasa Vyakarana [Nepal Bhasa Grammar] (in Nepali). Kathmandu: Royal Nepal Academy. p. 26.

- George Campbell,Compendium of the World's Languages: Ladakhi to Zuni, Volume 2

- Ayyappappanikkar; Akademi, Sahitya (January 1999). Medieval Indian literature: an anthology, Volume 3. p. 69. ISBN 9788126007882. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- Gellner, D.; Pfaff-Czarnecka, J.; Whelpton, J. (6 December 2012). Nationalism and Ethnicity in a Hindu Kingdom: The Politics and Culture of ... p. 243. ISBN 9781136649561. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- Giuseppe, Father (1799). "Account of the Kingdom of Nepal". Asiatick Researches. London: Vernor and Hood. Retrieved 29 May 2011. Pages 320–322.

- "History". Kathmandu Metropolitan City. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- Dixit, Kunda (6 August 2010). "The lake that was once Kathmandu". Nepali Times. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- Sanskrit: संक्षिप्त स्वयम्भू पुराण, राजेन्द्रमान बज्राचार्य

- Vajracharya, Dhanavajra and Malla, Kamal P. (1985) The Gopalarajavamsavali. Franz Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden GmbH.

- Shakya, Kedar (1998). "Status of Newar Buddhist Culture". Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- Vergati, Anne (July 1982). "Social Consequences of Marrying Visnu Nārāyana: Primary Marriage among the Newars of Kathmandu Valley". Contributions to Indian Sociology. Retrieved 2 June 2011. Page 271.

- Giuseppe, Father (1799). "Account of the Kingdom of Nepal". Asiatick Researches. London: Vernor and Hood. Retrieved 29 May 2011. Page 308.

- Kirkpatrick, Colonel (1811). An Account of the Kingdom of Nepaul. London: William Miller. Retrieved 29 May 2011. Page 123.

- Hamilton, Francis Buchanan (1819). "An Account of the Kingdom of Nepal and of the Territories Annexed to this Dominion by the House of Gorkha". Edinburgh: A. Constable. p. 232. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- Lewis, Todd T. "Buddhism, Himalayan Trade, and Newar Merchants". Buddhist Himalaya: A Journal of Nagarjuna Institute of Exact Methods. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 17 May 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Dyczkowski, Mark. "Goddess Kubjika and Her Immense Depth". The Trika Shaivism of Kashmir. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- At the Indo-Tibetan Interface http://web.comhem.se/~u18515267/CHAPTERII.htm#_ftn49 Archived 17 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Novak, Charles M. (1992). "A Portrait of Buddhism in Licchavi Nepal". Buddhist Himalaya: A Journal of Nagarjuna Institute of Exact Methods. Nagarjuna Institute of Exact Methods. 4 (1, 2). Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- Vergati, Anne (2009). "Image and Rituals in Newar Buddhism". Société Européenne pour l'Etude des Civilisations de l'Himalaya et de l'Asie Centrale. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- Diwasa, Tulasi; Bandhu, Chura Mani; Nepal, Bhim (2007). "The Intangible Cultural Heritage of Nepal: Future Directions" (PDF). UNESCO Kathmandu Series of Monographs and Working Papers: No 14. UNESCO Kathmandu Office. Retrieved 4 May 2011. Page 7.

- Malla, Kamal P. (1981). "Linguistic Archaeology of the Nepal Valley: A Preliminary Report". Kailash – Journal of Himalayan Studies. Ratna Pustak Bhandar. Retrieved 4 May 2011. Volume 8, Number 1 and 2, Page 18.

- "It's Nepal Bhasa". The Rising Nepal. 9 September 1995.

- Tuladhar, Prem Shanti (2000). Nepal Bhasa Sahityaya Itihas: The History of Nepalbhasa Literature. Kathmandu: Nepal Bhasa Academy. ISBN 99933-56-00-X. Pages 19–20.

- Malla, Kamal P. "The Earliest Dated Document in Nepal Bhasa: The Palmleaf from Uku Bahah NS 234/AD 1114". Kailash. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 January 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2012. Pages 15–25.

- Lienhard, Siegfried (1992). Songs of Nepal: An Anthology of Nevar Folksongs and Hymns. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas. ISBN 81-208-0963-7. Page 3.

- "Population Classified by First Language Spoken" (PDF). UNESCO Kathmandu Series of Monographs and Working Papers: No 14. UNESCO Kathmandu Office. 2007. Retrieved 4 May 2011. Page 48.

- Genetti, Carol (2007). A Grammar or Dolakha Newar. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. ISBN 978-3-11-019303-9. Page 11.

- Lienhard, Siegfried (1992). Songs of Nepal: An Anthology of Nevar Folksongs and Hymns. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas. ISBN 81-208-0963-7. Page 2.

- Tuladhar, Prem Shanti (2000). Nepal Bhasa Sahityaya Itihas: The History of Nepalbhasa Literature. Kathmandu: Nepal Bhasa Academy. ISBN 99933-56-00-X. Pages 14 and 306.

- "Classical Nepal Bhasa Literature" (PDF). Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- Malla, Kamal P. "The Earliest Dated Document in Nepal Bhasa: The Palmleaf from Uku Bahah NS 234/AD 1114". Kailash. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 January 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2011. Pages 15–25.

- Prajapati, Subhash Ram (2006). Pulangu Nepal Bhasa Natak Ya Sangeet Pakshya. newatech. ISBN 979-9994699925.CS1 maint: ignored ISBN errors (link)

- Lienhard, Siegfried (1992). Songs of Nepal: An Anthology of Nevar Folksongs and Hymns. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas. ISBN 81-208-0963-7. Page 1.

- Lienhard, Siegfried (1992). Songs of Nepal: An Anthology of Nevar Folksongs and Hymns. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas. ISBN 81-208-0963-7. Page 4.

- Newars assert Newa Autonomous State Himalayan Times

- Nepal govt urged to give autonomy to Newa state The Daily Star

- Restructure Districts of Nepal

- Newars assert Newa Autonomous State The Himalayan Times

- The need of Newa Autonomous State The demand of Newa Autonomous State also means to re-structure the districts. The territory of the State would consist every historical Newa settlement, spread East to Dapcha, Panauti, Dhulikhel, etc.; spread north to Tibet and the Newa towns of Dolakha; the Bajrabarahi, Kulekhani, Tistung and Chitlang of Makawanpur district; Nuwakot district up to the Trishuli(Sangu Khusi); Villages like Tauthali and other Newa villages of Sindupalchok.

- Prajapati, Subhash Ram (ed.) (2006) The Masked Dances of Nepal Mandal. Thimi: Madhyapur Art Council. ISBN 99946-707-0-0.

- "Charya Nritya and Charya Giti". Dance Mandal: Foundation for Sacred Buddhist Arts of Nepal. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- Lienhard, Siegfried (1992). Songs of Nepal: An Anthology of Nevar Folksongs and Hymns. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas. ISBN 81-208-0963-7. Page 9.

- Wegner, Gert-Matthias (1986). The Dhimaybaja of Bhaktapur: Studies in Newar Drumming I. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner. Nepal Research Center Publications No. 12. ISBN 3-515-04623-2.

- Vajracharya, Madansen (1998). "Lokabaja in Newar Buddhist Culture". Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- Grandin, Ingemar (1989). Music and Media in Local Life: Music Practice in a Newar Neighbourhood in Nepal. Linköping University. ISBN 978-91-7870-480-4. Page 67.

- Pal, Pratapaditya (1985). Art of Nepal: A Catalogue of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art Collection. University of California Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0520054073. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- American University (May 1964). "Sculpture, Painting and Handicrafts". Area Handbook for Nepal (with Sikkim and Bhutan). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved 28 April 2011. Page 105.

- "The Stuart Cary Welch Collection". Sotheby's. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- "History". Tibetan Buddhist Wall Paintings. 2003. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- "Newar Casters of Nepal". The Huntington Photographic Archive of Buddhist and Related Art at The Ohio State University. Archived from the original on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- Bangdel, Lain S. (1989) Stolen Images of Nepal. Kathmandu: Royal Nepal Academy. Page 22.

- Lieberman, Marcia R. (9 April 1995). "The Artistry of the Newars". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- Pommaret, Françoise (1994) Bhutan. Hong Kong: Twin Age. ISBN 978-962-217-341-5. Page 80.

- Alberge, Dalya (2 January 2011). "Bhutan's Endangered Temple Art Treasures". The Observer. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- van der Heide, Susanne. "Traditional Art In Upheaval: The Development Of Modern Contemporary Art In Nepal". Arts of Nepal. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- "Architectural jewels lost in haphazard urbanisation". The Himalayan Times. 27 January 2012. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- "Kathmandu Valley: Long Description". United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- American University (May 1964). "Architecture". Area Handbook for Nepal (with Sikkim and Bhutan). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved 28 April 2011. Pages 105–106.

- Hutt, Michael et al. (1994) Nepal: A Guide to the Art and Architecture of the Kathmandu Valley. Kiscadale Publications. ISBN 1-870838-76-9. Page 50.

- "Caste Ethnicity Population". Government of Nepal, National Planning Commission Secretariat, Central Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on 13 April 2011. Retrieved 8 May 2011. Pages 92–97.

- Hamilton, Francis Buchanan (1819). "An Account of the Kingdom of Nepal and of the Territories Annexed to this Dominion by the House of Gorkha". Edinburgh: A. Constable. Retrieved 27 May 2011. Page 194.

- Oliphant, Laurence (1852). "A Journey to Katmandu". London: John Murray. Retrieved 19 May 2011. Chapter VI.

- Vinding, Michael (1998). The Thakali: A Himalayan ethnography. Serindia Publications. p. 362. ISBN 978-0906026502.

- Hilker, D. S. Kansakar (2005) Syamukapu: The Lhasa Newars of Kalimpong and Kathmandu. Kathmandu: Vajra Publications. ISBN 99946-644-6-8.

- "Newars in Sikkim". Archived from the original on 20 April 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- Tuladhar, Kamal Ratna (2011) Caravan to Lhasa: A Merchant of Kathmandu in Traditional Tibet. Kathmandu: Lijala & Tisa. ISBN 99946-58-91-3. Page 112.

- "Newa International Forum Japan". Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- "Pasa Puchah Guthi UK". Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- "Newah Organization of America". Archived from the original on 28 April 2011. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- Anderson, Mary M. (1971) The Festivals of Nepal. Allen and Unwin. ISBN 978-0-04-394001-3.

- Vajracharya, Munindraratna (1998). "Karunamaya Jatra in Newar Buddhist Culture". Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- "Bhoto Jatra". Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- Levy, Robert I. (1991). "Biska: The Solar New Year Festival". Mesocosm: Hinduism and the Organization of a Traditional Newar City in Nepal. University of California Press. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- Manandhar, Asmita (3 June 2011). "Sithi Nakha: The Newar Environment Festival". Republica. Retrieved 3 June 2011. Page 14.

- Löwdin, Per (July 2002). "Food, Ritual and Society: A Study of Social Structure and Food Symbolism among the Newars". Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 1 May 2011. Doctoral dissertation, Department of Cultural Anthropology, University of Uppsala, Sweden.

- Tuladhar, Tara Devi (2011). Thaybhu: A Description of Feast Materials. Kathmandu: Chhusingsyar. ISBN 978-9937-2-3219-7.

- Shrestha, Bal Gopal (July 2006). "The Svanti Festival: Victory over Death and the Renewal of the Ritual Cycle in Nepal" (PDF). Contributions to Nepalese Studies. CNAS/TU. 33 (2): 206–221. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- Lewis, Todd T. "A Modern Newar Guide for Vajrayana Life-Cycle Rites". Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- Pradhan, Rajendra (1996). "Sacrifice, Regeneration and Gifts: Mortuary Rituals among Hindu Newars of Kathmandu" (PDF). CNAS Journal. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- Fisher, James F. (1978). Himalayan Anthropology: The Indo-Tibetan Interface. Great Britain: Mouton Publishers. p. 123. ISBN 90-279-7700-3.

- Bajracharya, Ratnakaji (1993). "Traditions of Newar Buddhist Culture". Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- ROSPATT, ALEXANDER VON (2005). "The Transformation of the Monastic Ordination (pravrajyā)". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

https://thehimalayantimes.com/kathmandu/khadgis-removed-from-list-of-dalits/

Further reading

- Bista, Dor Bahadur (2004). People of Nepal. Kathmandu: Ratna Pustak Bhandar.

- Encyclopædia Britannica (2011). Newar.

- Kayastha, Chhatra Bahadur (2003). Nepal Sanskriti: Samanyajnan. Nepal Sanskriti. ISBN 99933-34-84-7.

- Toffin, Gérard, "Newar Society", Kathmandu, Socia Science Baha/Himal Books, 2009.

- Löwdin, Per (2002) [1986]. "Food, Ritual and Society: A Study of Social Structure and Food Symbolism among the Newars". Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2013.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Scofield, John. Kathmandu's Remarkable Newars, in National Geographic, February 1979.

- Vajracharya, Gautama V. Elements of Newar Buddhist Art:Circle of Bliss – a review article.

External links

- A Window to Newar Culture (ज्वजलपा डट कम)

- Nepal Ethnographic Museum

- Art of Newar Buddhism

- Rashtriya Janajati Bikas Samiti

- An authentic source of information on Madhyapur Thimi, a rich Newar town

- Importance Of Wine In Newar Culture

- Journal of Newar Studies

- Newa Bigyan Journal of Newar Studies

- Newah Organization of America

- Newah Site Pasa Puchah Guthi, United Kingdom

- Amar Chitrakar

- Chitrakars

- Newars, new and old French scholar Gérard Toffin's work on Newars

- Newar Society: City, Village and Periphery. By Gérard Toffin's book review