Affair of the Dancing Lamas

The Affair of the Dancing Lamas was an Anglo–Tibetan diplomatic controversy stemming mainly from the visit to Britain in 1924–25 of a party of Tibetan monks (only one of whom was a lama) as part of a publicity stunt for The Epic of Everest – the official film of the 1924 British Mount Everest Expedition.

The Dalai Lama and the government of Tibet felt that the film and the pseudo-religious performances required of the monks ridiculed Tibetan culture – as a diplomatic protest they banned future Everest expeditions. The film had been the responsibility of John Noel, the expedition's photographer, but the mountaineering establishment was closely involved and to avoid embarrassment they shifted the blame for the ban on expeditions onto John de Vars Hazard, another member of the team, who had gone exploring off the authorised route. The true cause of the diplomatic fuss was kept secret and Hazard remained the scapegoat for over fifty years.

Historically, Tibet had not been willing to allow foreign explorers into the country but the 1921 British expedition had been permitted in connection with an arms deal. Monastic opposition to the arms and the expeditions increased until by 1925 the country was close to revolution. The Tibetan army chief was closely associated with the British and the debacle was probably partly responsible for his fall from grace in 1925. The subsequent decline of military influence within the Tibetan government may have made the country more vulnerable to the Chinese takeover in 1950.

Background

Diplomatic

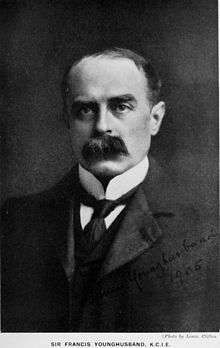

Fearing Russian military intervention into Tibet, in 1904 the British Raj made a military incursion into Tibet led by Francis Younghusband. Sometimes known as the "Mission to Lhasa", this was largely instigated by Lord Curzon, the Viceroy of India.[1] The ensuing 1904 treaty and 1906 convention formalised Chinese suzerainty over Tibet while declaring that it would permit no foreign interventions (including by Russia or Britain). In 1910 China invaded Tibet and to escape the savagery the Dalai Lama fled to Sikkim, where he was sheltered by the British. Sikkim, sandwiched between India and Tibet, was under firm British protection and was only nominally an independent state.[2]

Following the Xinhai Revolution, which established the Republic of China in 1912, China withdrew from Tibet. The Dalai Lama returned to Lhasa and Britain briefly supplied armaments to what it now regarded as an independent country but the First World War in Europe led to Britain losing interest.[3] By 1919 a renewed fear of Russia and China felt by both Britain and Tibet led to a mutual desire for closer diplomatic relations. Charles Bell, Britain's political representative in Sikkim, was sent to Lhasa at the end of 1920 to negotiate. He was the first European to be invited to Lhasa and he stayed for almost a whole year.[4] Bell and Thubten Gyatso, the Dalai Lama, developed a warm personal friendship.[5] In 1921, Britain again started supplying Tibet with arms, ammunition, military support and training.[4]

British aspirations towards Mount Everest

On his 1904 military mission, Younghusband had seen Mount Everest, the highest mountain in the world. and had enthused Curzon with the idea of a grand British imperial expedition to make the first ascent of the mountain. Eventually this led to Britain's magisterial Alpine Club adopting the idea in celebration of its 1907 golden jubilee.[6] Mount Everest lies on the border between Nepal and Tibet but neither country would allow entry to foreign expeditions. The Secretary of State for India refused to request permission from Tibet and then the 1914–18 War intervened.[7]

In 1913 John Noel had entered Tibet clandestinely and had reached to within forty miles of Mount Everest, closer than any other foreigner before him.[8] After the war, in an attempt to inject new impetus, Noel was invited to address a joint meeting of the Royal Geographical Society and the Alpine Club. Noel's 1919 talk was inspirational and the two societies again started lobbying.[9] Younghusband (soon to become president of the RGS) wrote to the Secretary of State for India to see if Tibet could be asked for permission. Even with the political backing of Lord Curzon, who was now Britain's Foreign Secretary (and who had been RGS president from 1911 to 1914), Younghusband only received lukewarm support from Whitehall but was still able to send Charles Howard-Bury to India to try to take things forward. Howard-Bury met the Viceroy of India, Lord Chelmsford, who was sympathetic but said he could do nothing while negotiations with Tibet were pending, although he suggested that Charles Bell should be approached.[5] By serendipity, Howard-Bury met Bell shortly before Bell's diplomatic visit to Lhasa. As a small piece in the diplomatic jigsaw, Bell negotiated that British expeditions be allowed into Tibet, starting with the 1921 British Mount Everest reconnaissance expedition.[10] However, in the minds of the Tibetan elite, Everest expeditions became associated with military expansionism within the country.[11]

Early in 1921 the Mount Everest Committee was set up jointly by the Royal Geographical Society and the Alpine Club to manage all future British expeditions – Younghusband was appointed chairman.[12]

1922 and 1924 Mount Everest expeditions

John Noel was photographer on the 1922 Everest expedition and was made responsible for producing the subsequent official film, Climbing Mount Everest.[14] Shown in cinemas around Britain it had been a reasonable success. When the 1924 expedition was being planned Noel offered to fund £8,000 of the estimated £9,000 total cost of the expedition if he was allowed to make a second film and retain all the rights to it and other photography.[14][15] Noel, who was quite a showman, was determined to make the film a success and he planned filming in such a way that he could produce a mountaineering epic if the summit attempt succeeded or a Tibet travelogue if it failed.[14]

On 8 June 1924 Mallory and Irvine set off for the summit, never to return.[16]

For those on the expedition at the time, the loss of Mallory and Irvine did not seem like the magnificent tragedy it was soon to become.[17] Noel raced back to civilisation to start work on his film; John Hazard went to the West Rongbuk Glacier to do further surveying but then went beyond his remit by going north to Lhatse and the upper part of the Tsangpo River; the others went to the Rongshar Valley[note 1] to recuperate before the long trek home.[18][19][20] In Britain matters were treated differently – the climbers' memorial service in St Paul's Cathedral was attended by King George V, the Prince of Wales and the Duke of York.[18]

The Epic of Everest

The Times had the scoop headline "Everest: The Last Climb: Hopes That Summit Was Reached", and Noel's 1924 film, according to Wade Davis, "elevated Mallory ... into the realm of the Titans".[21] Noel's film The Epic of Everest: The Immortal Film Record of This Historic Expedition had its premiere at the New Scala Theatre on 8 December 1924.[14][note 2]

A production company Explorers' Films, with Younghusband as chairman, had been set up to make the film.[24] Because there was no film footage high on the mountain and it was not known if the summit had been reached, Noel planned a total theatrical experience. The stage setting was a Tibetan courtyard with shimmering Himalayan peaks painted on the backdrop. To provide what Noel called "large doses of local colour", before the film started a group of monks was to come on stage equipped with ethnic accoutrements to perform pseudo-religious music, chanting and dance.[25][note 3] The headline in the Daily Sketch "High Dignitaries of Tibetan Church Reach London; Bishop to dance on Stage; Music from Skulls" was not couched in terms that the Tibetan authorities would wish for. The performers were genuinely monks (despite the publicity proclaiming "seven lamas", there was in reality only one) but they were from nowhere near Mount Everest and they had been inveigled out of Tibet without permission from their superior.[25][27] To the satisfaction of the press when the monks went to the London Zoo they were shown the llamas.[28] To begin with the show was a critical and public success. It toured Britain and Germany and over a million people in the United States and Canada went to see it.[25] However, the political difficulties turned things sour and by the end of 1925 Explorers' Films had gone bankrupt in Colombo, requiring the Mount Everest Committee to send £150 to get the monks back to India.[29] Only a few of them returned to Tibet and those who did were severely punished.[30]

Diplomatic representations from Tibet

The government of Tibet lodged an official diplomatic protest. They believed that the film, and its accompanying carnival, ridiculed Tibet. They found particularly offensive a scene showing a man delousing a child and then eating the lice.[31][32][note 4] After seeing the performance the Permanent Under-Secretary of State for India wrote that it was "unspeakably boring" but that it could not cause "more than that smile of kindly superiority which we generally assume when we see or hear of strange customs".[33]

The Dalai Lama regarded the film and the monks' performances as a direct affront to his religion and called for the arrest of the monks.[34][35] Noel initially said he had received official permission to take them from Tibet but this was found to be false. In Britain an official inquiry reported, "Captain Noel's statement about the monks taken to England is in direct variance with the facts". The Mount Everest Committee was forced into an apology: "The Committee regret very deeply the humiliating position in which they were placed by the discovery that Captain Noel's statements were incorrect".[36] The prime minister of Tibet's note demanding the monks' return ended with "For the future, we cannot give permission to go to Tibet" and no more expeditions were allowed until 1933.[34][37]

In Tibet the matter was extremely sensitive because at the time that country was close to revolution. The modernisation and militarisation being introduced by the Dalai Lama and the head of the army, Tsarong Dzasa, were deeply unacceptable to the governing religious conservatives who were opposed to any British presence or influence. They had good reason to be so opposed – Britain was secretly trying to provoke an uprising in support of the military, although this ultimately failed and Tsarong had to escape to Sikkim.[34]

The affair may have had long-term effects beyond mountaineering – when China invaded in 1950 Tibet no longer had an effective army and could offer little military resistance.[34]

Cover-up and scapegoat

The Mount Everest Committee was unable to distance itself from the film – it had supported its production and benefited financially. It therefore laid the blame elsewhere for the diplomatic catastrophe and for over fifty years the cover-up succeeded in public, the impression being given that Hazard's unauthorised detour was to blame for the ban on expeditions.[38]

In 1969, as the last item under "Accidents, Equipment and Miscellaneous Notes", the Alpine Club in its Alpine Journal reported the death of John Hazard (spelling his name incorrectly) and made it clear that he had never been a Club member. The obituary said he had been "something of a misfit", best remembered for leaving four Sherpas behind at the North Col in 1924, requiring "very risky rescue operations" by other members of the party. After the expedition, he had gone off the main route with "a porter or two to the Tsango Po river on a jaunt of his own". The report concluded that such detours had been acceptable in 1921 and apologised for in 1922, but in 1924 it was the last straw and Lhasa had clamped down on expeditions for nine years.[39][note 5] In the 1990 Alpine Journal's obituary of John Noel the dancing lamas are not mentioned at all.[40]

By 1996, however, the Alpine Journal was willing to publish an article entitled "The Scapegoat" by Audrey Salkeld, the Everest historian. In it she reviews Hazard's life and his role concerning the Sherpas on the North Col and his unauthorised Tsangpo journey. She concludes that the Tibetans' strongest complaint was over the monks' publicity visit and credits Walt Unsworth with uncovering the "dancing lama furore" in 1981.[38] The diplomatic affair had been swept under the carpet for over fifty years because Younghusband (president of the RGS and chairman of the Mount Everest Committee) must have been aware of, or even a party to, the scheme to invite the monks.[20]

"The Affair of the Dancing Lamas"

In 1981 Walt Unsworth revealed in his book Everest that "The Affair of the Dancing Lamas" was the primary reason why Mount Everest expeditions had been again banned by Tibet.[41][42][note 6] The main blame for the diplomatic incident is indeed laid on Noel rather than Hazard but Unsworth views the position of the Tibetan government differently from the more recent accounts of Hansen and Davis, whose analysis has been given above.

When in 1921 Charles Bell retired from being effectively the British diplomatic service for Sikkim and Tibet, Frederick Bailey took over. Whereas Bell had been a classical scholar and Tibetologist,[44][45] Bailey was an adventurer. He had accompanied Younghusband to Lhasa on his 1904 "mission" and later had made a lengthy, arduous and illegal excursion into Tibet to explore the Tsangpo Gorge.[46] As poacher turned gamekeeper he went out of his way to hinder expeditions to Tibet – or at least that was the view of the mountaineering establishment in London. Unsworth says it was for reasons unknown, possibly personal ambition, whereas Salkeld says he was believed to have scores to settle with the Mount Everest Committee.[47][20] He was exceptionally well placed to be awkward as he was the single point of contact between London and Lhasa and so was inevitably involved in passing on and composing diplomatic notes for both sides.[48] Unsworth supports the "Mount Everest Committee view" in seeing Bailey as the creator of much of the antipathy towards expeditions whilst relying on mere acquiescence from Lhasa.[49] Hansen explicitly rejects this view and regards it as a British "orientalist" attitude that people in Tibet were merely primitive and backward.[50] He criticises Unsworth (and the Mount Everest Committee and others) for denying any independent agency to the Tibetans. Hansen claims that Lhasa did indeed drive the diplomatic protests for rational reasons and Bailey tended to go along with them.[51] The authors agree that the India Office in London became enraged by the Mount Everest Committee's indiscretions and it suited everyone concerned in the debacle to keep the whole thing quiet.[52][53][20]

Notes

- The Rongshar Valley is near the Nepalese border close to Nangpa La.

- A trailer can be viewed online and there is a 2013 review.[22][23]

- A newsreel of the monks in Britain is available online.[26]

- Whether they were lice or fleas seems to have had diplomatic significance but the identification was never resolved.

- This paragraph is based on remarks of a similar tone made by Audrey Salkeld in the Alpine Journal of 1996.[38]

- In his preface Unsworth credits Salkeld for "a great deal of the research".[43]

References

Citations

- Hansen (1996), p. 717.

- Davis (2012), pp. 118–120.

- Davis (2012), pp. 120–122.

- Davis (2012), p. 123-124.

- Davis (2012), pp. 112–113.

- Davis (2012), pp. 63–74.

- Davis (2012), pp. 74–75.

- Davis (2012), pp. 80–83.

- Davis (2012), pp. 86–100.

- Davis (2012), pp. 123–124.

- Hansen (1996), p. 719.

- Davis (2012), pp. 125–126.

- Davis (2012), p. 484.

- Davis (2012), p. 561.

- Unsworth (1981), p. 147.

- Davis (2012), p. 2.

- Davis (2012), pp. 550–554.

- Davis (2012), p. 557.

- Unsworth (1981), p. 145.

- Salkeld (1996), p. 226.

- Davis (2012), pp. 557, 384.

- BFI Trailers (2013).

- Horell (2013).

- Davis (2012), p. 468.

- Davis (2012), pp. 561–562.

- British Pathé (1924).

- "Winter Garden: The Epic of Everest". Gloucestershire Echo. British Newspaper Archive. 20 June 1925. p. 5. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- Hansen (1996), p. 732.

- Unsworth (1981), p. 156.

- Hansen (1996), p. 738.

- Davis (2012), p. 562.

- Unsworth (1981), p. 150.

- Hansen (1996), p. 712.

- Davis (2012), pp. 563–564.

- Hansen (1996), p. 737.

- Hansen (1996), p. 736.

- Perrin (2013), p. 154.

- Salkeld (1996), pp. 224–226.

- Alpine Journal (1969).

- Hattersley-Smith (1990), pp. 315–317.

- Salkeld (1996), p. 226, : referring to Unsworth (1981), pp. 142–157

- Unsworth (1981), pp. 142–157, : chapter 6, "The Affair of the Dancing Lamas".

- Unsworth (1981), p. xi.

- Unsworth (1981), p. 75.

- Davis (2012), pp. 113–114.

- Unsworth (1981), p. 142.

- Unsworth (1981), pp. 143, 157.

- Unsworth (1981), pp. 142–143, 150–151.

- Unsworth (1981), p. 157.

- Hansen (1996), p. 713.

- Hansen (1996), pp. 713, 736.

- Unsworth (1981), pp. 155–156.

- Hansen (1996), pp. 736–737.

Works cited

- "Accidents, Equipment and Miscellaneous Notes" (PDF). Alpine Journal: 350. 1969. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- BFI Trailers (2013). The Epic of Everest (1924) - Trailer (trailer). British Film Institute. Retrieved 16 May 2015 – via YouTube.

- British Pathé (1924). The Epic of Everest (newsreel). British Pathé. Retrieved 16 May 2015 – via YouTube.

- Davis, Wade (2012). Into the Silence: The Great War, Mallory, and the Conquest of Everest. Random House. ISBN 978-0099563839.

- Hansen, Peter H. (June 1996). "The Dancing Lamas of Everest: Cinema, Orientalism, and Anglo-Tibetan Relations in the 1920s". American Historical Review. Oxford University Press. 101 (3): 712–747. doi:10.2307/2169420. JSTOR 2169420.

- Hattersley-Smith, Geoffrey (1990). "In Memoriam: John Baptist Lucien Noel 1890–1989" (PDF). Alpine Journal. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- Horell, Mark (30 October 2013). "The Epic of Everest – Captain John Noel's film of the 1924 expedition". Footsteps on the Mountain. Mark Horell. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- Perrin, Jim (2013). Shipton and Tilman. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 9780091795467.

- Salkeld, Audrey (1996). "The Scapegoat" (PDF). Alpine Journal: 224–226. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- Unsworth, Walt (1981). Everest. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 0713911085.