Andrew Irvine (mountaineer)

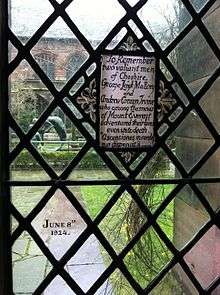

Andrew Comyn "Sandy" Irvine (8 April 1902 – 8 or 9 June 1924) was an English mountaineer who took part in the 1924 British Everest Expedition, the third British expedition to the world's highest (8,848 m) mountain, Mount Everest.

Andrew Irvine | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Andrew Comyn Irvine 8 April 1902 Birkenhead, Cheshire, England |

| Died | 8–9 June 1924 (aged 22) North Face, Mount Everest, Tibet |

| Cause of death | Mountaineering accident |

| Occupation | Student at Merton College, Oxford |

While attempting the first ascent of Mount Everest, he and his climbing partner George Mallory disappeared somewhere high on the mountain's northeast ridge. The pair was last sighted only a few hundred metres from the summit, and it is unknown if the pair reached the summit before they perished. Mallory's body was found in 1999, but Irvine's body has never been found.

Early life

Irvine was born in Birkenhead, Cheshire, one of six children of historian William Fergusson Irvine (1869–1962) and Lilian Davies-Colley (1870–1950).[1][2] His father's family had Scottish and Welsh roots, whilst his mother was from an old Cheshire family. He was a cousin of journalist and writer Lyn Irvine, and also of pioneering female surgeon Eleanor Davies Colley and of political activist Harriet Shaw Weaver.

He was educated at Birkenhead School and Shrewsbury School,[3] where he demonstrated a natural engineering acumen, able to improvise fixes or improvements to almost anything mechanical. During the First World War, he created a small stir at the War Office by sending them a design for a synchronisation gear to allow a machine gun to fire from a propeller-driven aeroplane through the propeller without damaging its blades, and also a design for a gyroscopic stabiliser for aircraft.[4]

He was also a keen sportsman and particularly excelled at rowing. His prodigious ability as a rower made him a star of the 1919 'Peace Regatta' at Henley with the Royal Shrewsbury School Boat Club,[5] and propelled him to Merton College, Oxford, to study engineering. At Oxford, he joined the Oxford University Mountaineering Club, and was also a member of the Oxford crew for the Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race in 1922 and a member of the winning crew in 1923,[3] the only time Oxford won between 1913 and 1937.

He had a relationship with a former chorus girl named Marjory Agnes Standish Summers (née Thompson), who at the age of 19 had married Harry Summers, then aged 52, in 1917. Summers was one of the founders of John Summers & Sons, a steel company. While Irvine was on Everest, Harry began divorce proceedings against Marjory.[6][7]

Everest expedition

In 1923, Irvine took part in the Merton College Arctic Expedition to Spitsbergen,[3] where he excelled on every front. The expedition's leader, Noel Odell, and he discovered that they had met before in 1919 on Foel Grach, a 3000-foot-high Welsh mountain, when Irvine had ridden his motorcycle to the top and surprised Odell and his wife Mona, who had climbed it on foot.[8] Subsequently, on Odell's recommendation, Irvine was invited to join the forthcoming third British Mount Everest expedition on the grounds that he might be the "superman" that the expedition felt it needed. He was at the time still a 21-year-old undergraduate student.

Irvine set sail for the Himalayas from Liverpool on board the SS California on 29 February 1924,[9] along with three other members of the expedition, including George Mallory. Mallory later wrote home to his wife that Irvine "could be relied on for anything except perhaps conversation".

During the expedition, he made major and crucial innovations to the expedition's professionally designed oxygen sets, radically improving their functionality, lightness, and strength. He also maintained the expedition's cameras, camp beds, primus stoves, and many other devices. He was universally popular, and respected by his older colleagues for his ingenuity, companionability, and unstinting hard work.

The expedition made two unsuccessful attempts on the summit in early June, and time remained for one more before the heavy snowfall that came with the summer monsoon would make climbing too dangerous. This last chance fell to the expedition's most experienced climber, George Mallory. To the surprise of other expedition members, Mallory chose the 22-year-old inexperienced Irvine above the older, more seasoned climber, Noel Odell. Irvine's proficiency with the oxygen equipment was obviously a major factor in Mallory's decision, but some debate has occurred ever since about the precise reasons for his choice.[10]

Mallory and Irvine began their ascent on 6 June, and by the end of the next day, the pair had established a final two-man camp at 8,168 m (26,800 ft), from which to make their final push on the summit. What time they departed on 8 June is unknown, but circumstantial evidence suggests that they did not have the smooth, early start that Mallory had hoped for.[10]

Noel Odell, who was acting in a supporting role, reported seeing them at 12:50 pm – much later than expected – ascending what he believed was the Second Step of the northeast ridge and "going strongly for the top",[11] although in the years that followed, exactly which of the Three Steps Odell had sighted the pair climbing became extremely controversial.

Whether they reached the summit has never been established. They never returned to their camp and died somewhere high on the mountain. The discovery of Mallory's body in 1999, with its severe rope jerk injury about his waist, suggests the two were roped when they fell. Irvine's body has never been discovered.

Traces on the ridge

Discovery of the ice-axe

In 1933, some 9 years after the disappearance of Mallory and Irvine, Percy Wyn-Harris, a member of the fourth British Everest Expedition discovered an ice axe around 8,460 m (27,760 ft), about 20 m below the ridge and some 230 m before the First Step. It was found lying loose on brown 'boiler-plate' slabs of rock, which though not particularly steep, were smooth and in places had a covering of loose pebbles.[12] The Swiss manufacturer's name matched those of a number supplied to the 1924 expedition, and since only Mallory and Irvine had climbed that high along the ridge route, it must have belonged to one of them.

Hugh Ruttledge, leader of the 1933 expedition, speculated that the ice axe marked the scene of a fall, during which it was either accidentally dropped or that its owner put it down possibly to have both hands free to hold the rope.[13] Noel Odell, the last man to see Mallory and Irvine on their ascent in 1924, offered a more benign explanation: that the ice axe had merely been placed there on the ascent to be collected on the way back in view of the fact that the climbing ahead was almost entirely on rock under the prevailing conditions.[14][15]

In 1963, a characteristic triple nick mark on a military swagger stick, found among Andrew Irvine's possessions, was found to match a similar mark on the ice axe's shaft, making it likely that the ice axe belonged to Irvine,[16] although some doubt exists as to whether the marks were present on the ice axe when it was discovered.[17]

Discovery of the oxygen cylinder

In May 1991, a 1924 oxygen cylinder was found around 8,480 m (27,820 ft), some 20 m higher and 60 m closer to the First Step than the ice axe found in 1933 (although it was not recovered until May 1999).[15] Since only Mallory and Irvine had been on the NE ridge in 1924, this oxygen cylinder marked the minimum altitude they must have reached on their final climb.

Discovery of Mallory

In May 1999, Mallory's body was found at 8,155 m (26,760 ft) by the Mallory and Irvine Research Expedition, in a funnel-shaped basin on the "8,200 m Snow Terrace", some 300 m below and about 100 m horizontal to the location of the ice axe found in 1933.[18][19][20] The remains of a rope still encircled his waist, which exhibited serious haemorrhaging, indicative of a strong rope-jerk injury, and strongly suggesting that at some point either Mallory or Irvine fell while they were still roped together. Mallory was found with relatively few major injuries, compared to a number of modern climbers who had fallen the full distance from the NE Ridge and who were found very broken up, suggesting he had survived this initial fall, and suffered a further accident. The presence of a golf ball-sized puncture wound in his forehead seemed to be the likely cause of death,[21] and could have been inflicted by an ice-axe. It has subsequently been speculated that an injured Mallory was descending in a self-arrest "glissade", sliding down the slope while dragging his ice-axe in the snow to control the speed of his descent, and that his ice-axe may have struck a rock and bounced off, striking him fatally.

A search of the body revealed two pieces of circumstantial evidence that suggested that Mallory might have reached the summit:

- Firstly, Mallory's daughter had always said that Mallory carried a photograph of his wife on his person with the intention of leaving it on the summit when he reached it,[22] and no such photograph was found on the body. Given the excellent state of preservation of the body and the artifacts recovered from it, the absence of the photograph suggests that he may have reached the summit and deposited it there.

- Secondly, Mallory's snow goggles were in his pocket when the body was found, indicating that he died at night. This implies that he and Irvine had made a push for the summit and were descending very late in the day. Given their known departure time and movements, had they not made the summit, it is unlikely that they would have still been out by nightfall.

Significantly, the search revealed no trace of either of the two Vest Pocket Kodak cameras[22] that the pair were known to be carrying from Irvine's diaries, leading to speculation that at least one of the cameras must have been in Irvine's possession. Experts from Kodak have stated that if one of the cameras is found, there is a good chance that the film could be developed to produce "printable images", due to the nature of the black and white film that was used and the fact that it has, in effect, been in "deep freeze" for over three-quarters of a century.[23] Such images would potentially illuminate the fate of Mallory and Irvine more clearly than any other evidence.

Possible sightings

Sighting by Wang Hong-bao

In 1979, Ryoten Hasegawa, the leader of the Japanese contingent of a Sino-Japanese reconnaissance expedition to the north side of Everest, had a brief conversation with a Chinese climber named Wang Hong-bao, in which Wang recounted that whilst on the 1975 Chinese Everest Expedition, he had seen the body of an "old British dead" at 8,100 m, lying on his side as if asleep at the foot of a rock. Wang knew the man was British, he said, by the old-fashioned clothing, rotted and disintegrating at the touch, and poked his finger into his cheek to indicate an injury.[10][24][25] However, before more information could be obtained, Wang was killed in an avalanche the following day.

Further confirmation of this sighting was provided by a 1986 conversation American Everest historian Tom Holzel had with Wang's tent-mate from the 1975 expedition, Zhang Junyan, who admitted that Wang had come back from a short excursion lasting about 20 minutes and described finding "a foreign mountaineer" at "8,100 m."[26] Since no other European climber was known to have died at that elevation on the North side of Everest, it was almost certain that the body was either George Mallory or Andrew Irvine.

Wang's 1975 sighting was the key to the discovery of Mallory's body 24 years later in the same general area, although his reported description of the body he found, "hole in cheek", is not consistent with the condition and posture of Mallory's body, which was face down, his head almost completely buried in scree, and with a golfball-sized puncture wound on his forehead, leaving open the possibility that Wang may have seen Irvine instead. The second Mallory and Irvine Research Expedition in 2001 discovered Wang's 1975 campsite location and made an extensive search of its surroundings, and found that Mallory's remained the only body in the vicinity. One explanation of the apparent discrepancy between Wang's description and the state Mallory's body was discovered in, is that Wang, having discovered the body face up, may have turned the body over to effect a simple burial.

Sighting by Xu Jing

In 2001, Eric Simonson, leader of the 1999 Mallory and Irvine Expedition, and German researcher Jochen Hemmleb, who inspired it, travelled to Beijing to interview some of the remaining survivors of the 1960 Chinese Everest expedition, which had been the first expedition back to the north side since the British attempts of the 1920s and 1930s.

During their meeting, the deputy leader of the expedition, Xu Jing, spontaneously blurted out that on his descent from the First Step, he recalled having spotted a dead climber lying on his back, feet facing uphill, in a hollow or slot in the rock. Since no one other than Mallory and Irvine had ever been lost on the north side of Everest before 1960, and Mallory had been found much lower down, it was almost a certainty that Xu had discovered Irvine. However, the sighting was brief, and Xu was in desperate straits during the descent, and while he clearly remembered seeing the body, he was unclear about where it was.[22][27][28]

Sighting by Wang Fu-chou

However, a more contemporary account, not dulled by the passage of 40 years, has subsequently surfaced. In 1965, a member of the 1960 Chinese expedition, Wang Fu-chou gave a lecture in the headquarters of the USSR Geographical Society in Leningrad. While describing the expedition, Wang Fu-chou, made a sensational remark: "At an altitude of about 8,600 meters we found a corpse of a European". Asked how he could be sure the dead man was European, the Chinese climber replied simply, "He was wearing braces".[29][30]

Recent searches

In 2010, a team informally dubbed the Andrew Irvine Search Committee led by American Everest historian Tom Holzel conducted a new photographic search for Irvine using a computer-assembled montage of aerial photographs taken in 1984 by Brad Washburn and the National Geographic Society. This search led to the identification of a possible object at about 8,425 metres, less than 100 m from the ice-axe location, consistent with a body lying in a slot of rock, feet pointing toward the summit, just as Xu described his sighting.[31]

A new expedition organised by Tom Holzel was due to explore the upper slopes of Everest in December 2011, presumably with a view to determining the nature of this possible object.[31] By conducting the expedition in winter, it was hoped that there would be much less snow on the upper slopes, increasing the chances of finding Irvine, as well as the camera that it is hoped will be with him.[32]

In 2019, Mark Synott led a party which investigated the 'crevice' identified by Holzel as the potential resting place of Irvine, but discovered that it was merely an optical illusion.[33]

Comments by friends of Irvine

- Upon hearing of Irvine and Mallory's disappearance, a family friend wrote: "One cannot imagine Sandy content to float placidly in some quiet back-water, he was the sort that must struggle against the current and, if need be, go down foaming in full body over the precipice".[34]

- Arnold Lunn, one of Irvine's friends, wrote: "Irvine did not live long, but he lived well. Into his short life he crowded an overflowing measure of activity which found its climax in his last wonderful year, a year during which he rowed in the winning Oxford boat, explored Spitsbergen, fell in love with skiing, and – perhaps – conquered Everest. The English love rather to live well than to live long".

Scholarships

Andrew Comyn Irvine Scholarships are awarded to Oxford University students on a yearly basis to fund mountaineering trips. They are awarded to students who carry on the spirit of determination and endurance that Andrew C. Irvine was known for.

See also

References

- Davis, Wade (2012). Into the Silence: The Great War, Mallory, and the Conquest of Everest. Random House Incorporated. ISBN 0375708154.

- Firstbrook, Peter (1999). Lost on Everest: The Search for Mallory & Irvine. London: BBC Worldwide Ltd. ISBN 0-563-55129-1.

- Holzel, Tom; Salkeld, Audrey (1999). The Mystery of Mallory and Irvine (2nd Revised ed.). London: Pimlico.

- Ruttledge, Hugh (2011) [1934]. Everest 1933. London: Read Books.

- Summers, Julie (2000). Fearless on Everest: The Quest for Sandy Irvine. London: Iffley Press. ISBN 978-0-9564795-0-1.

- Footnotes

- Summers, p. xiii

- "Everest Man's Father Dies - Was Noted Historian". Liverpool Echo. 6 March 1962. p. 1. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- Levens, R.G.C., ed. (1964). Merton College Register 1900–1964. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. p. 145.

- Davis

- "Everest needs you, Mr Irvine" (PDF). Shrewsbury School. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- "Caro's Family Chronicles". Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- "Book review of Fearless on Everest by Julie Summers, see WP article". The Observer. 29 October 2000. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- "Mount Everest The British Story". Everest1953.co.uk. 8 June 1924. Archived from the original on 14 February 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- "George Leigh Mallory". everestnews.com. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- Firstbrook, p. 130

- "Jochen Hemmleb: The Last Witness: Noel Odell". Affimer.org. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- Ruttledge, H. (1934). "The Mount Everest Expedition, 1933", Alpine Journal, 45, p. 226

- Ruttledge, Everest 1933, p. 145

- Odell, N.E. (1934). "The ice-axe found on Everest", Alpine Journal, 46

- "Jochen Hemmleb: First Traces: 1933–1991". Affimer.org. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- Odell, N.E. (1963). "The ice-axe found on Everest in 1933", Alpine Journal, 68, 141

- Morgan, Ivor (1 December 2006). "Everest 1924: December 2006". Everest1924.blogspot.com. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- "Random Images: George Mallory, 1 May 1999". Mountainworld.typepad.com. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- "Everest Image with landmarks". Jochenhemmleb.com. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- "Jochen Hemmleb: Mallory & Irvine Research Expedition, 1999". Affimer.org. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- "Jochen Hemmleb: Second Search, May 1999". Affimer.org. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- Hellen, Nicholas. (2003). "Body may prove who was first up Everest", The Sunday Times, 27 April

- https://web.archive.org/web/20130131081340/http://news.discovery.com/history/us-history/mallory-irvine-camera-everest-expedition.htm

- Suzuki, H. (1980). American Alpine Journal, 22, p. 658

- Holzel, Tom. "Mallory and Irvine The Final Chapter: The Second Attempt to Search for Mallory and Irvine". Everestnews.com. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- Holzel & Salkeld, p. 327

- "Jochen Hemmleb: Was Andrew Irvine Found in 1960?". Affimer.org. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- "Mallory and Irvine The Final Chapter: Xi Jing". Everestnews2004.com. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- "Home of the Daily and Sunday Express | Express Yourself:: Mount Everest's death zone". Daily Express. 23 April 2010. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- "First Time to Summit Everest from the North (Vpervye na Everest s severa)". St.Petersburg Alpine Club, Russia. 2002. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- Peter Beaumont and Ed Douglas (7 August 2011). "Everest expedition to find Irvine's remains slammed as 'distasteful' | The Observer". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- mtracy99 (26 April 2017). "Using Google Earth Pro to find the Ice Axe". Mallory & Irvine. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- https://www.nationalgeographic.co.uk/adventure/2020/06/our-team-climbed-everest-to-try-to-solve-its-greatest-mystery

- Julie Summers (2000). Fearless on Everest: The Quest for Sandy Irvine. Mountaineers. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-89886-796-1.

External links

- Everest News on Sandy Irvine

- Altitude Everest Expedition 2007, retracing Mallory and Irvine's last steps on Everest.

- AC Irvine Travel Fund

- Mallory and Irvine Memorials