Abenaki

The Abenaki (Abnaki, Abinaki, Alnôbak) are a Native American tribe and First Nation. They are one of the Algonquian-speaking peoples of northeastern North America. The Abenaki originate in what is now called Quebec and the Maritimes of Canada and in the New England region of the United States, a region called Wabanahkik ("Dawn Land") in the Eastern Algonquian languages. The Abenaki are one of the five members of the Wabanaki Confederacy.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| > 9,775 (2016) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States (Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont) Canada (New Brunswick, Quebec) | |

| Canada | 9,775[1] |

| Languages | |

| English, French, Abenaki | |

| Religion | |

| Now largely Roman Catholic Originally Abenaki religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Algonquian peoples | |

"Abenaki" is a linguistic and geographic grouping; historically, there was no strong central authority – the Abenaki were composed of numerous smaller bands and tribes who shared many cultural traits.[2] They came together as a post-contact community after their original tribes were decimated by colonization, disease, and warfare.

Name

The word Abenaki and its syncope, Abnaki, are both derived from Wabanaki, or Wôbanakiak, meaning "People of the Dawn Land" in the Abenaki language.[3] While the two terms are often confused, the Abenaki are one of several tribes in the Wabanaki Confederacy.

Wôbanakiak is derived from wôban ("dawn" or "east") and aki ("land")[4] (compare Proto-Algonquian *wa·pan and *axkyi) — the aboriginal name of the area broadly corresponding to New England and the Maritimes. It is sometimes used to refer to all the Algonquian-speaking peoples of the area—Western Abenaki, Eastern Abenaki, Wolastoqiyik-Passamaquoddy, and Miꞌkmaq—as a single group.[3]

The Abenaki people also call themselves Alnôbak, meaning "Real People" (c.f., Lenape language: Lenapek) and by the autonym Alnanbal, meaning "men".[2]

Subdivisions

Historically, ethnologists have classified the Abenaki by geographic groups: Western Abenaki and Eastern Abenaki. Within these groups are the Abenaki bands:

|

|

Location

The homeland of the Abenaki, which they call Ndakinna (our land), extended across most of what is now northern New England, southern Quebec, and the southern Canadian Maritimes. The Eastern Abenaki population was concentrated in portions of New Brunswick and Maine east of New Hampshire's White Mountains. The other major tribe, the Western Abenaki, lived in the Connecticut River valley in Vermont, New Hampshire and Massachusetts.[7] The Missiquoi lived along the eastern shore of Lake Champlain. The Pennacook lived along the Merrimack River in southern New Hampshire. The maritime Abenaki lived around the St. Croix and Wolastoq (Saint John River) valleys near the boundary line between Maine and New Brunswick.

The English settlement of New England and frequent wars forced many Abenaki to retreat to Quebec. The Abenaki settled in the Sillery region of Quebec between 1676 and 1680, and subsequently, for about twenty years, lived on the banks of the Chaudière River near the falls, before settling in Odanak and Wôlinak in the early eighteenth century.

In those days, the Abenaki practiced a subsistence economy based on hunting, fishing, trapping, berry picking and on growing corn, beans, squash, potatoes and tobacco. They also produced baskets, made of ash and sweet grass, for picking wild berries, and boiled maple sap to make syrup. Basket weaving remains a traditional activity for members of both communities.

During the Anglo-French wars, the Abenaki were allies of France, having been displaced from Ndakinna by immigrating English people. An anecdote from the period tells the story of a Maliseet war chief named Nescambuit or Assacumbuit, who killed more than 140 enemies of King Louis XIV of France and received the rank of knight. Not all Abenaki natives fought on the side of the French, however; many remained on their native lands in the northern colonies. Much of the trapping was done by the people and traded to the English colonists for durable goods. These contributions by Native American Abenaki peoples went largely unreported.

Two tribal communities formed in Canada, one once known as Saint-Francois-du-lac near Pierreville, Quebec (now called Odanak, Abenaki for "coming home"), and the other near Bécancour (now known as Wôlinak) on the south shore of the Saint Lawrence River, directly across the river from Trois-Rivières. These two Abenaki reserves continue to grow and develop. Since the year 2000, the total Abenaki population (on and off reserve) has doubled to 2,101 members in 2011. Approximately 400 Abenaki reside on these two reserves, which cover a total area of less than 7 square kilometres (2.7 sq mi). The unrecognized majority are off-reserve members, living in various cities and towns across Canada and the United States.

There are about 3,200 Abenaki living in Vermont and New Hampshire, without reservations, chiefly around Lake Champlain. The remaining Abenaki people live in multi-racial towns and cities across Canada and the US, mainly in Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and northern New England.[2]

Four Abenaki tribes are located in Vermont. On April 22, 2011, Vermont officially recognized two Abenaki tribes: the Nulhegan Band of the Coosuk-Abenaki and the Elnu Abenaki Tribe. On May 7, 2012, the Abenaki Nation at Missisquoi and the Koasek Traditional Band of the Koas Abenaki Nation received recognition by the State of Vermont. The Nulhegan are located in the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont, with tribal headquarters in Brownington, and the Elnu Abenaki are located in southeastern Vermont with tribal headquarters in Jamaica, Vermont. The Elnu Abenaki tribe focuses mainly on carrying on the traditions of their ancestors through their children and teaching about their culture.[8] The chief and political leader of the Nulhegan Band is Don Stevens.[9] The Sokoki (the Abenaki Nation at Missisquoi) are located along the Missisquoi River in northwestern Vermont, with tribal headquarters in Swanton. Their traditional land is along the river, extending to its outlet at Lake Champlain.[6]

In December 2012, Vermont's Nulhegan Abenaki Tribe created a tribal forest in the town of Barton. This forest was established with assistance from the Vermont Sierra Club and the Vermont Land Trust. It contains a hunting camp and maple sugaring facilities that are administered cooperatively by the Nulhegan. The forest contains 65 acres (26 ha).[10]

The St Francis Missisquoi Tribe owns forest land in the town of Brunswick, centered around the Brunswick Springs. These springs are believed to be a sacred traditional religious site of the Abenaki. Together these Vermont forests are the only Abenaki held lands outside of the existing reservations in Quebec and Maine.

Language

The Abenaki language is closely related to the Panawahpskek (Penobscot) language. Other neighboring Wabanaki tribes, the Pestomuhkati (Passamaquoddy), Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet), and Miꞌkmaq, and other Eastern Algonquian languages share many linguistic similarities. It has come close to extinction as a spoken language. Tribal members are working to revive the Abenaki language at Odanak (means "in the village"), a First Nations Abenaki reserve near Pierreville, Quebec, and throughout New Hampshire, Vermont and New York state.

The language is holophrastic, meaning that a phrase or an entire sentence is expressed by a single word. For example, the word for "white man" awanoch is a combination of the words awani meaning "who" and uji meaning "from". Thus, the word for "white man" literally translates to "Who is this man and where does he come from?"

History

In Reflections in Bullough's Pond, historian Diana Muir argues that the Abenakis' neighbors, pre-contact Iroquois, were an imperialist, expansionist culture whose cultivation of the corn/beans/squash agricultural complex enabled them to support a large population. They made war primarily against neighboring Algonquian peoples, including the Abenaki. Muir uses archaeological data to argue that the Iroquois expansion onto Algonquian lands was checked by the Algonquian adoption of agriculture. This enabled them to support their own populations large enough to have sufficient warriors to defend against the threat of Iroquois conquest.[11]

In 1614, Thomas Hunt captured 24 young Abenaki people and took them to England.[12] During the European colonization of North America, the land occupied by the Abenaki was in the area between the new colonies of England in Massachusetts and the French in Quebec. Since no party agreed to territorial boundaries, there was regular conflict among them. The Abenaki were traditionally allied with the French; during the reign of Louis XIV, Chief Assacumbuit was designated a member of the French nobility for his service.

Facing annihilation from English attacks and epidemics of new infectious diseases, the Abenaki started to emigrate to Quebec around 1669. The governor of New France allocated two seigneuries (large self-administered areas similar to feudal fiefs). The first was on the Saint Francis River and is now known as the Odanak Indian Reservation; the second was founded near Bécancour and is called the Wolinak Indian Reservation.

Abenaki wars

When the Wampanoag people under King Philip (Metacomet) fought the English colonists in New England in 1675 in King Philip's War, the Abenaki joined the Wampanoag. For three years they fought along the Maine frontier in the First Abenaki War. The Abenaki pushed back the line of white settlement through devastating raids on scattered farmhouses and small villages. The war was settled by a peace treaty in 1678, with the Wampanoag more than decimated and many Native survivors having been sold into slavery in Bermuda.[13]

During Queen Anne's War in 1702, the Abenaki were allied with the French; they raided numerous small English villages in Maine, from Wells to Casco, killing about 300 settlers over ten years. They also occasionally raided into Massachusetts, for instance in Groton and Deerfield in 1704. The raids stopped when the war ended. Some captives were adopted into the Mohawk and Abenaki tribes; older captives were generally ransomed, and the colonies carried on a brisk trade.[14]

The Third Abenaki War (1722–25), called Father Rale's War, erupted when the French Jesuit missionary Sébastien Rale (or Rasles, 1657?-1724) encouraged the Abenaki to halt the spread of Yankee settlements. When the Massachusetts militia tried to seize Rasles, the Abenaki raided the settlements at Brunswick, Arrowsick, and Merry-Meeting Bay. The Massachusetts government then declared war and bloody battles were fought at Norridgewock (1724), where Rasles was killed, and at a daylong battle at the Indian village near present-day Fryeburg, Maine, on the upper Saco River (1725). Peace conferences at Boston and Casco Bay brought an end to the war. After Rale died the Abenaki moved to a settlement on the St. Francis River.[15]

The Abenaki from St. Francois continued to raid British settlements in their former homelands along the New England frontier during Father Le Loutre's War (see Northeast Coast Campaign (1750)) and the French and Indian War.

Canada

The development of tourism projects has allowed the Canadian Abenaki to develop a modern economy, while preserving their culture and traditions. For example, since 1960, the Odanak Historical Society has managed the first and one of the largest aboriginal museums in Quebec, a few miles from the Quebec-Montreal axis. Over 5,000 people visit the Abenaki Museum annually. Several Abenaki companies include: in Wôlinak, General Fiberglass Engineering employs a dozen natives, with annual sales exceeding C$3 million. Odanak is now active in transportation and distribution. Notable Abenaki from this area include the documentary filmmaker Alanis Obomsawin (National Film Board of Canada).[16]

United States

The Penobscot Indian Nation, Passamaquoddy people, and Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians have been federally recognized as tribes in the United States.[17]

Vermont

In 2006, the state of Vermont officially recognized the Abenaki as a people, but not a tribe. The state noted that many Abenaki had been assimilated, and only small remnants remained on reservations during and after the French and Indian War, later eugenics projects further decimated the Abenaki people of America through forced sterilization and questionable 'miscarriages' at birth.[18] As noted above, facing annihilation, many Abenaki had begun emigrating to Canada, then under French control, around 1669.

The Sokoki-St. Francis Band of the Abenaki Nation organized a tribal council in 1976 at Swanton, Vermont. Vermont granted recognition of the council the same year, but later withdrew it. In 1982, the band applied for federal recognition, which is still pending.[2] Four Abenaki communities are located in Vermont. On April 22, 2011, Vermont officially recognized two Abenaki bands: the Nulhegan Band of the Coosuk-Abenaki and the El Nu Abenaki Tribe. On May 7, 2012, the Abenaki Nation at Missisquoi and the Koasek of the Koas Abenaki Traditional Band received recognition by the State of Vermont. The Abenaki who chose to remain in the United States did not fare as well as their Canadian counterparts. Tribal connections were lost as those Abenaki who were tolerated by the Anglo population were assimilated into colonial society. What familial groups remained were often eradicated, in the early 20th century, through forced sterilization and pregnancy termination policies in Vermont.[19] There were over 3,400 reported cases of sterilization of Abenaki having been performed, many of which involved termination of an unborn fetus. No documentation of informed consent for these procedures was found. After this period the only Abenaki that remained in the United States were those who could pass for white, or avoid capture and subsequent dissolution of their families through forced internment in "schools" after their sterilization. At the time, many of the children who were sterilized were not even aware of what the physicians had done to them. This was performed under the auspices of the Brandon School of the Feeble-Minded, and the Vermont Reform School. It was documented in the 1911 "Preliminary Report of the Committee of the Eugenic Section of the American Breeder's Association to Study and to Report on the Best Practical Means for Cutting Off the Defective Germ-Plasm in the Human Population."[20][21]

Official state tribal recognition

The Vermont Elnu (Jamaica) and Nulhegan (Brownington) bands' application for official recognition was recommended and referred to the Vermont General Assembly by the Vermont Commission on Native American Affairs on January 19, 2011, as a result of a process established by the Vermont legislature in 2010. Recognition allows applicants to seek scholarship funds reserved for American Indians and to receive federal "native made" designation for the bands' arts and crafts.[23]

On April 22, 2011, Vermont officially recognized two Abenaki bands: the Nulhegan Band of the Coosuk-Abenaki and the El Nu Abenaki Tribe. On May 7, 2012, the Abenaki Nation at Missisquoi and the Koasek Traditional Band of the Koas Abenaki Nation received recognition by the State of Vermont.

New Hampshire and minority recognition

In New Hampshire the Abenaki, along with other Native American groups, have proposed legislation for recognition as a minority group. This bill was debated in 2010 in the state legislature. The bill would create a state commission on Native American relations, which would act as an advisory group to the governor and the state government in general.[24] The Abenaki want to gain formal state recognition as a people.

Some people have opposed the bill, as they fear it may lead to Abenaki land claims for property now owned and occupied by European Americans. Others worry that the Abenaki may use recognition as a step toward opening a casino. But, the bill specifically says that "this act shall not be interpreted to provide any Native American or Abenaki person with any other special rights or privileges that the state does not confer on or grant to other state residents."[6] New Hampshire has considered expanding gambling separate from the Native Americans.[25]

The council would be under the Department of Cultural Resources,[24] so it would be in the same department as the State Council on the Arts. The bill would allow for the creation and sale of goods to be labeled as Native-made, to create a source of income for the Natives in New Hampshire.

The numerous groups of Natives in the state have created a New Hampshire Inter-tribal Council, which holds statewide meetings and powwows. Dedicated to preserving the culture of the Natives in New Hampshire, the group is one of the chief supporters of the HB 1610; the Abenaki, the main tribe in the state, are the only people named specifically in the bill.[26]

Culture

There are a dozen variations of the name "Abenaki", such as Abenaquiois, Abakivis, Quabenakionek, Wabenakies and others.

The Abenaki were described in the Jesuit Relations as not cannibals, and as docile, ingenious, temperate in the use of liquor, and not profane.[27]

All Abenaki tribes lived a lifestyle similar to the Algonquian-speaking peoples of southern New England. They cultivated crops for food, and located their villages on or near fertile river floodplains. Other less major, but still important, parts of their diet included game and fish from hunting and fishing, and wild plants.[2]

They lived in scattered bands of extended families for most of the year. Each man had different hunting territories inherited through his father. Unlike the Iroquois, the Abenaki were patrilineal. Bands came together during the spring and summer at temporary villages near rivers, or somewhere along the seacoast for planting and fishing. These villages occasionally had to be fortified, depending on the alliances and enemies of other tribes or of Europeans near the village. Abenaki villages were quite small when compared to those of the Iroquois; the average number of people was about 100.[2]

Most Abenaki crafted dome-shaped, bark-covered wigwams for housing, though a few preferred oval-shaped long houses. During the winter, the Abenaki lived in small groups further inland. The homes there were bark-covered wigwams shaped in a way similar to the teepees of the Great Plains Indians.[2] During the winter, the Abenaki lined the inside of their conical wigwams with bear and deer skins for warmth. The Abenaki also built long houses similar to those of the Iroquois.[28]

The Abenaki hold on to their traditions and ways of life in several ways. The Sokoki do so in the current constitution for their government. It has a chief, a council of elders, and methods and means for election to the council and chieftainship, as well as requirements for citizenship in the tribe.[29] They also list many of the different traditions they uphold, such as the different dances they perform and what those dances mean.[6] During several of these dances there is no photography allowed, out of respect for the culture. For several, there are instructions such as "All stand while it is sung" or "All Stand to Show Respect."[6]

Hair style and other marriage traditions

Traditionally, Abenaki men kept their hair long and loose. When a man found a girlfriend, he would tie his hair. When he married, he would attach the hair of the scalp with a piece of leather and shave all but the ponytail. The modernized spiritual version has the man with a girlfriend tying his hair and braiding it. When he marries, he keeps all his hair in a braid, shaving only the side and back of the head. The spiritual meaning surrounding this cut is most importantly to indicate betrothal or fidelity as a married Abenaki man. In much the same way as the Christian marriage tradition, there is an (optional) exchange and blessing of wedding rings. These rings are the outward and visible sign of the unity of this couple.[30][31][32]

Changes in the hair style were symbolic of a complex courtship process. The man would give the woman a box made of a fine wood, which was decorated with the virtues of the woman; the woman would give a similar box to the man. Everyone in the tribe must agree to the marriage. They erect a pole planted in the earth, and if anyone disagrees, he strikes the pole. The disagreement must be resolved or the marriage does not happen.[33]

Gender, food, division of labor, and other cultural traits

The Abenaki were a farming society that supplemented agriculture with hunting and gathering. Generally the men were the hunters. The women tended the fields and grew the crops.[34] In their fields, they planted the crops in groups of "sisters". The three sisters were grown together: the stalk of corn supported the beans, and squash or pumpkins provided ground cover and reduced weeds.[34] The men would hunt bears, deer, fish, and birds.

The Abenaki were a patrilineal society, which was common among New England tribes. In this they differed from the six Iroquois tribes to the west in New York, and from many other North American Indian tribes who had matrilineal societies. In those systems, women controlled property and hereditary leadership was passed through the women's line. Children born to a married couple belonged to the mother's clan, and her eldest brother was an important mentor, especially for boys. The biological father had a lesser role.[2]

Group decision-making was done by a consensus method. The idea is that every group (family, band, tribe, etc.) must have equal say, so each group would elect a spokesperson. Each smaller group would send the decision of the group to an impartial facilitator. If there was a disagreement, the facilitator would tell the groups to discuss again. In addition to the debates, there was a goal of total understanding for all members. If there was not total understanding, the debate would stop until there was understanding.

When the tribal members debate issues, they consider the Three Truths:

- Peace: Is this preserved?

- Righteousness: Is it moral?

- Power: Does it preserve the integrity of the group?

These truths guide all group deliberations, and the goal is to reach a consensus. If there is no consensus for change, they agree to keep the status quo.[35]

Storytelling

Storytelling is a major part of Abenaki culture. It is used not only as entertainment but also as a teaching method. The Abenaki view stories as having lives of their own and being aware of how they are used. Stories were used as a means of teaching children behavior. Children were not to be mistreated, and so instead of punishing the child, they would be told a story.[36]

One of the stories is of Azban the Raccoon. This is a story about a proud raccoon that challenges a waterfall to a shouting contest. When the waterfall does not respond, Azban dives into the waterfall to try to outshout it; he is swept away because of his pride. This story would be used to show a child the pitfalls of pride.[37]

Mythology

Ethnobotany

The Abenaki smash the flowers and leaves of Ranunculus acris and sniff them for headaches.[38] They consume the fruit of Vaccinium myrtilloides as part of their traditional diet.[39] They also use the fruit[40] and the grains of Viburnum nudum var. cassinoides [41] for food.[42]

Many other plants are used for various healing and treatment modalities, including for the skin, as a disinfectant, as a cure-all, as a respiratory aid, for colds, coughs, fevers, grippe, gas, blood strengthening, headaches and other pains, rheumatism, demulcent, nasal inflammation, anthelmintic, for the eyes, abortifacent, for the bones, antihemorrhagic, as a sedative, anaphrodisiac, swellings, urinary aid, gastrointestinal aid, as a hemostat, pediatric aid (such as for teething), and other unspecified or general uses.[43]

They use Hierochloe odorata, Apocynum, Betula papyrifera, Fraxinus americana, Fraxinus nigra, Laportea canadensis, a variety of Salix species, and Tilia americana var. americana for making baskets, canoes, snowshoes, and whistles.[44] They use Hierochloe odorata and willow to make containers, Betula papyrifera to create containers, moose calls and other utilitarian pieces, and the bark of Cornus sericea ssp. sericea for smoking.[45]

They also use Acer rubrum, Acornus calamus, an unknown Amelanchier species, Caltha palustris, Cardamine diphylla, Cornus canadensis, an unknown Crataegus species, Fragaria virginiana, Gaultheria procumbens, Osmunda cinnamomea, Phaseolus vulgaris, Photinia melanocarpa, Prunus virginiana, Rubus idaeus and another unknown Rubus species, Solanum tuberosum, Spiraea alba var. latifolia, Vaccinium angustifolium, and Zea mays as a tea, soup, jelly, sweetener, condiment, snack, or meal.[46]

Population and epidemics

Before the Abenaki, except the Pennacook and Miꞌkmaq, had contact with the European world, their population may have numbered as many as 40,000. Around 20,000 would have been Eastern Abenaki, another 10,000 would have been Western Abenaki, and the last 10,000 would have been Maritime Abenaki. Early contacts with European fishermen resulted in two major epidemics that affected Abenaki during the 16th century. The first epidemic was an unknown sickness occurring sometime between 1564 and 1570, and the second one was typhus in 1586. Multiple epidemics arrived a decade prior to the English settlement of Massachusetts in 1620, when three separate sicknesses swept across New England and the Canadian Maritimes. Maine was hit very hard during the year of 1617, with a fatality rate of 75%, and the population of the Eastern Abenaki fell to about 5,000. The more isolated Western Abenaki suffered fewer fatalities, losing about half of their original population of 10,000.[2]

The new diseases continued to strike in epidemics, starting with smallpox in 1631, 1633, and 1639. Seven years later, an unknown epidemic struck, with influenza passing through the following year. Smallpox affected the Abenaki again in 1649, and diphtheria came through 10 years later. Smallpox struck in 1670, and influenza in 1675. Smallpox affected the Native Americans in 1677, 1679, 1687, along with measles, 1691, 1729, 1733, 1755, and finally in 1758.[2]

The Abenaki population continued to decline, but in 1676, they took in thousands of refugees from many southern New England tribes displaced by settlement and King Philip's War. Because of this, descendants of nearly every southern New England Algonquian tribe can be found among the Abenaki people. A century later, fewer than 1,000 Abenaki remained after the American Revolution.

In the 1990 U.S. Census, 1,549 people identified themselves as Abenaki. So did 2,544 people in the 2000 U.S census, with 6,012 people claiming Abenaki heritage.[3] In 1991 Canadian Abenaki numbered 945; by 2006 they numbered 2,164.[3]

Fiction

Lydia Maria Child wrote of the Abenaki in her short story, "The Church in the Wilderness" (1828). Several Abenaki characters and much about their 18th-century culture are featured in the Kenneth Roberts novel Arundel (1930). The film Northwest Passage (1940) is based on a novel of the same name by Roberts.

The Abenaki are featured in Charles McCarry's historical novel Bride of the Wilderness (1988), and James Archibald Houston's novel Ghost Fox (1977), both of which are set in the eighteenth century; and in Jodi Picoult's Second Glance (2003) and Lone Wolf (2012) novels, set in the contemporary world. Books for younger readers both have historical settings: Joseph Bruchac's The Arrow Over the Door (1998) (grades 4–6) is set in 1777; and Beth Kanell's young adult novel, The Darkness Under the Water (2008), concerns a young Abenaki-French Canadian girl during the time of the Vermont Eugenics Project, 1931–1936.

The first sentence in Norman Mailer's novel Harlot's Ghost makes reference to the Abenaki: "On a late-winter evening in 1983, while driving through fog along the Maine coast, recollections of old campfires began to drift into the March mist, and I thought of the Abnaki Indians of the Algonquin tribe who dwelt near Bangor a thousand years ago."

Non-fiction

Letters and other non-fiction writing can be found in the anthology Dawnland Voices. Selections include letters from leader of the early praying town, Wamesit in Massachusetts Samuel Numphow, Sagamore Kancamagus, and writings on the Abenaki language by former chief of the reserve at Odanak in Quebec, Joseph Laurent as well as many others.

Accounts of life with the Abenaki can be found in the captivity narratives written by women taken captive by the Abenaki from the early New England settlements: Mary Rowlandson (1682), Hannah Duston (1702); Elizabeth Hanson (1728); Susannah Willard Johnson (1754); and Jemima Howe (1792).[47]

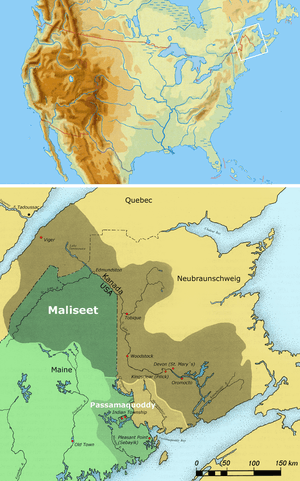

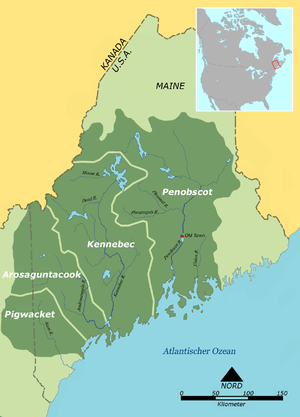

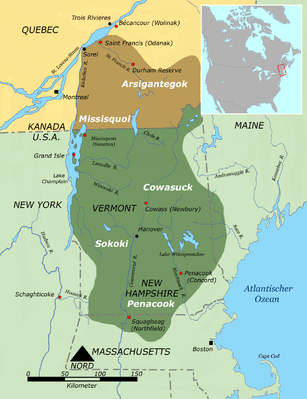

Maps

Maps showing the approximate locations of areas occupied by members of the Wabanaki Confederacy (from north to south):

Notable people

- Jesse Bruchac, author and linguist[48]

- Joseph Bruchac, author[49]

- Indian Joe, a scout around the time of the American Revolutionary War[50]

- Billy Kidd, former alpine ski racer[51]

- Joseph Laurent, chief and author[52]

- Henry Lorne Masta, chief and author[53]

- Donna L. Moody, repatriation activist

- Alanis Obomsawin, filmmaker and documentarian[54]

- Annick Obonsawin, voice actress and singer

- Donald E. Pelotte, Roman Catholic Bishop of Gallup (New Mexico and Arizona)[55]

- Cheryl Savageau, poet [56]

- Christine Sioui-Wawanoloath, writer and artist living in Quebec[57]

- Elijah Tahamont, silent film actor Dark Cloud[58]

- Alexis Wawanoloath, member of National Assembly of Quebec[59]

Footnotes

- "Data tables, 2016 census". Statistics Canada. 25 October 2017.

- Lee Sultzman (July 21, 1997). "Abenaki History". Archived from the original on 11 April 2010. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- "Abenaki". U*X*L Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. 2008. Archived from the original on 2014-06-11. Retrieved 2012-08-14 – via HighBeam Research.

- Snow, Dean R. 1978. "Eastern Abenaki". In Northeast, ed. Bruce G. Trigger. Vol. 15 of Handbook of North American Indians, ed. William C. Sturtevant. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, pg. 137. Cited in Campbell, Lyle (1997). American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pg. 401. Campbell uses the spelling wabánahki.

- Colin G. Calloway: The Western Abenakis of Vermont, 1600–1800: War, Migration, and the Survival of an Indian People, University of Oklahoma Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0806125688

- "Who We Are". Abenaki Nation. Archived from the original on 10 February 2010. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- Waldman, Carl. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes: Third Edition (New York: Checkmark Books, 2006) p. 1

- "Elnu Abenaki Tribe". Archived from the original on 26 May 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- "Contact Information for Federally Recognized Tribes of New Hampshire, New Hampshire Historical Resources". www.nh.gov. Retrieved 2018-10-02.

- "Nulhegan Abenaki attain first tribal forestland in more than 200 years". VTDigger. 2012-12-18. Retrieved 2018-11-15.

- Muir, Diana, Reflections in Bullough's Pond, University Press of New England.

- Bourne, Russell (1990). The Red King's Rebellion, Racial Politics in New England 1675–1678. p. 214. ISBN 0-689-12000-1.

- "Worlds rejoined". Cape Cod online.

- Kenneth Morrison, The Embattled Northeast: the Elusive Ideal of Alliance in Abenaki-Euramerican Relations (1984)

- Spencer C. Tucker; et al., eds. (2011). The Encyclopedia of North American Indian Wars, 1607–1890: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 249. ISBN 9781851096978.

- "Administration". Cbodanak.com. Archived from the original on 2012-07-20. Retrieved 2012-10-30.

- "Tribal Directory". U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs. Archived from the original on December 23, 2012. Retrieved December 26, 2012.

- "Vermont: Eugenics: Compulsory Sterilization in 50 American States". University of Vermont. Archived from the original on December 28, 2014. Retrieved December 31, 2014.

- Gallagher, Nancy (1999). Breeding Better Vermonters: The Eugenics Project in the Green Mountain State. Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England. pp. 80–82.

- "Vermont Eugenics". Uvm.edu. 1931-03-31. Archived from the original on 2012-11-01. Retrieved 2012-10-30.

- Henrik Palmgren. "The Horrifying American Roots of Nazi Eugenics". Redicecreations.com. Archived from the original on 2012-10-15. Retrieved 2012-10-30.

- "Keewakwa Abenaki Keenahbeh - Whispering Giant Sculptures on Waymarking.com". Groundspeak, Inc. June 28, 2006. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- Hallenbeck, Terri. Abenaki Turn to Vermont Legislature for Recognition Burlington Free Press January 20, 2011. Retrieved January 20, 2011

- "HB 1610-FN – As Amended by the House". NH General Court. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- "Gambling Bill Would Create 6 Casinos, Allow Black Jack". WMUR.com. March 4, 2010. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- "The New Hampshire Inter-Tribal Native American Council: Mission Statement". Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed. (1900). Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New France, 1610—1791. The Burrows Company. Archived from the original on 2006-09-07. Retrieved 2006-11-07.

- Waldman, Carl (2006). Encyclopedia of Native American tribes (3rd ed.). New York: Facts on File. ISBN 9780816062737. OCLC 67361229.

- Constitution of the Sovereign Republic of the Abenaki Nation of Missisquoi

- The Encyclopedia of Native American Costume

- The Cowasuck Band of the Pennacook Abenaki People

- Verbal teachings (Oral Traditions) from the late "Berth Daigle"

- "Marriage or Wedding Ceremony". Cowasuck Band of the Pennacook-Abenaki People. Archived from the original on August 19, 2010. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- "What We Ate". Cowasuck Band of the Pennacook-Abenaki People. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- "The Consensual Decision-Making Process". Cowasuck Band of the Pennacook-Abenaki People. Archived from the original on August 8, 2010. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- Joe Bruchac. "The Abenaki Perspective on Storytelling". Abenaki Nation. Archived from the original on 10 February 2010. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- "Raccoon and the Waterfall". Abenaki Nation. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- Rousseau, Jacques 1947 Ethnobotanique Abenakise. Archives de Folklore 11:145–182 (p. 166)

- Rousseau, Jacques, 1947, Ethnobotanique Abenakise, Archives de Folklore 11:145-182, page 152, 171

- Rousseau, Jacques, 1947, Ethnobotanique Abenakise, Archives de Folklore 11:145-182, page 152

- Rousseau, Jacques, 1947, Ethnobotanique Abenakise, Archives de Folklore 11:145-182, page 173

- A full list of their ethnobotany can be found at the Native American Ethnobotany Database (159 documented plant uses).

- "BRIT - Native American Ethnobotany Database". naeb.brit.org. Retrieved 2019-12-17.

- "BRIT - Native American Ethnobotany Database". naeb.brit.org. Retrieved 2019-12-17.

- "BRIT - Native American Ethnobotany Database". naeb.brit.org. Retrieved 2019-12-17.

- "BRIT - Native American Ethnobotany Database". naeb.brit.org. Retrieved 2019-12-17.

- Women's Indian Captivity Narratives, ed. Kathryn Zabelle Derounian-Stodola, Penguin, London, 1998

- Senier, Siobhan (2014). Dawnland voices: an anthology of indigenous writing from New England. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803256798. OCLC 884725772.

- "Joseph Bruchac Biography". josephbruchac.com. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- Johnson, Arthur (2007). "Biography of Indian Joe". nedoba.org. Ne-Do-Ba (Friends), A Maine Nonprofit Corporation. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- Boyd, Janet. "Famous Abenaki - Snow Riders". www.snow-riders.org. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- "Conseil des Abenakis Odanak". Archived from the original on 2015-04-04.

- Brooks, Lisa (2008). The Common Pot: The Recovery of Native Space in the Northeast (NED - New ed.). University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816647835. JSTOR 10.5749/j.ctttsd1b.

- "Alanis Obomsawin: the vision of a native filmmaker". ProQuest 225762692.

- "Most Rev. Donald E. Pelotte". Diocese of Gallup. Archived from the original on 2008-05-09. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- "Cheryl Savageau's Poetic Awikhiganak". ProQuest 817563374.

- "Christine Sioui Wawanoloath" (in French). Terres en vues/Land InSights. Archived from the original on 2016-08-13.

- Chamberlain, Alexander F. (April 1903). "Algonkian Words in American English: A Study in the Contact of the White Man and the Indian". The Journal of American Folklore. American Folklore Society. 16 (61): 128–129. doi:10.2307/533199. JSTOR 533199.

- "Biography of Alexis Wawanoloath". Dictionnaire des parlementaires du Québec de 1792 à nos jours (in French). National Assembly of Quebec.

Bibliography

- Aubery, Joseph Fr. and Stephen Laurent, 1995. Father Aubery's French Abenaki Dictionary: English translation. S. Laurent (Translator). Chisholm Bros. Publishing

- Baker, C. Alice, 1897. True Stories of New England Captives Carried to Canada during the Old French and Indian Wars. Press of E.A. Hall & Company, Greenfield, Massachusetts

- Charland, Thomas-M. (O.P.), 1964. Les Abenakis D'Odanak: Histoire des Abénakis D'Odanak (1675–1937). Les Éditions du Lévrier, Montreal, QC

- Coleman, Emma Lewis. New England Captives Carried to Canada: Between 1677 and 1760 During the French and Indian Wars, Heritage Books, 1989 (reprint 1925).

- Day, Gordon, 1981. The Identity of the Saint Francis Indians, National Museums of Canada, Ottawa, National Museum Of Man Mercury Series ISSN 0316-1854, Canadian Ethnology Service Paper No. 71 ISSN 0316-1862.

- Laurent, Joseph, 1884. New Familiar Abenakis and English Dialogues. Quebec: Joseph Laurent (Sozap Lolô Kizitôgw), Abenakis, Chief of the Indian village of St. Francis, P.Q. Reprinted (paperback) Sept. 2006: Vancouver: Global Language Press, ISBN 0-9738924-7-1; Dec. 2009 (hardcover): Kessinger Publishings Legacy Reprint Series; and April 2010 (paperback): Nabu Press.

- Masta, Henry Lorne, 1932. Abenaki Legends, Grammar and Place Names. Victoriaville, PQ: La Voix Des Bois-Franes. Reprinted 2008: Toronto: Global Language Press, ISBN 978-1-897367-18-6

- Maurault, Joseph-Anselme (Abbot), 1866. Histoire des Abénakis, depuis 1605 jusqu'à nos jours. Published at L'Atelier typographique de la "Gazette de Sorel", QC

- Moondancer and Strong Woman, 2007. A Cultural History of the Native Peoples of Southern New England: Voices from Past and Present. Boulder, CO: Bauu Press, ISBN 0-9721349-3-X

Further reading

Other grammar books and dictionaries include:

- Dr. Gordon M. Day's two-volume Western Abenaki Dictionary (August 1994), Paperback: 616 pages, Publisher: Canadian Museum Of Civilization

- Chief Henry Lorne Masta's Abenaki Legends, Grammar, and Place Names (1932), Odanak, Quebec, reprinted in 2008 by Global Language Press

- Joseph Aubery's Father Aubery's French-Abenaki Dictionary (1700), translated into English-Abenaki by Stephen Laurent, and published in hardcover (525 pp.) by Chisholm Bros. Publishing.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Abenaki. |

- Missisquoi Abenaki Tribal Council

- Koasek Traditional Band of the Koas Abenaki Nation

- Nulhegan Abenaki Tribe

- Elnu Tribe of the Abenaki

- Abenakis of Odanak Council

- "Welcome to the Abenaki Language"

- Native Languages of the Americas: Abnaki-Penobscot (Abenaki Language)

- Abenaki language - recordings

- Western Abenaki Dictionary and Radio Online

- Gordan M. Day, "The Identity of the St. Francis Indians"

.svg.png)