Cowasuck

The Cowasuck, also known as Cowass, was an Algonquian-speaking Native American tribe in northeastern North America, linguistically and culturally belonging to the Western Abenaki as well as being members of the Abenaki Confederation.[1] Today, the Cowasuck Band of the Pennacook-Abenaki People also known as Cowass North American, a nonprofit corporation, claims to be the encompassing organization of these peoples descendants.[2]

Name

The name Cowasuck comes from the Abenaki word Goasek and means "white pines place", the name of an area near Newbury, Vermont.[3][4] The members of the tribe were called Goasi, plural Goasiak, which means "the people of the white pines".[5] Variant names of the place are Koés in French and Cohass, Cohoss, or Coos in English, and an alternate demonym is Cohassiac.[6]

Original Location

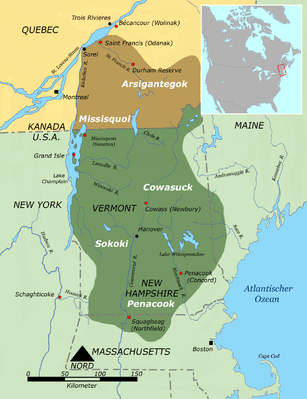

The Cowasuck formerly resided on the upper Connecticut River, with the main village of Cowasuck, now Newbury, located in the states of New Hampshire and Vermont.[7] The river valley forest was a mixture of deciduous trees, hemlocks, and white pines, growing on light soils or old fields.[8] The villages were typically set up on the edge of a cliff, both near the alluvial land suitable for growing maize, and with sufficient water supply. All villages were close to a river or lake, which served for fishing and as a travel route. Their wigwams were rectangular, covered with bark, had domed roofs with a hole as a flue for each fire, and had room for several families.

History

The best early accounts of the Western Abenaki came from the French, who knew them as converts and friends, but the French preoccupation consisted of proselytizing and fighting the English. However, the French practice of calling the Cowasuck by the name Penacook, and the Sokoki - originally the French name for the Mahican - led to misunderstandings in their reports. As a result, the tribes of the Western Abenaki were referred to only by their respective village names, which were considered tribal names.

French missionaries

The first French priests of the Jesuit Order came to New France around 1611. Unlike the grey-robed Puritans in New England, the Jesuits did not insist on making the natives French, but first of all Christians. From oral traditions of the Abenaki, it is known that the French missionaries were active since 1615 in Abenaki villages on the shores of Lake Champlain.[9]

Jesuit Fathers often acted both as military and political agents of the French crown and as servants of God. They traveled alone in the indigenous land, visited the villages of the Abenaki and took part in the life of the indigenous people.[10] Some of them, like Father Sébastien Rale, became intimate connoisseurs of Native American culture. He produced an extensive dictionary of the Abenaki language.[11]

The missionaries learned the language of the natives, adopted their style of speech, and tried as far as possible to follow their customs and manners. They had no interest in the Abenaki land, in their women, nor in the fur trade. Their poverty and devotion were respected and their courage, as well as their apparent immunity to the diseases that the communities healers faced helplessly, was admired by the natives. They shared the lives of the indigenous peoples and earned their trust, although their missionary vocation demanded that they renounce Native American culture, the disempowerment of religious leaders, and the spiritual and social revolution. The missionaries were the lawyers for the Abenaki and helped them to better overcome the differences between Native American and European culture. Sometimes they also represented the Abenaki in negotiations with the English. Men like Sébastien Rale became central figures in the Abenaki story. Soon the Abenaki were reputed to be the most pious Catholics and to be among the most loyal Native American friends of New France.

20th century

The descendants of the Cowasuck live today in small groups distributed mainly in New Hampshire and Vermont. Neither New Hampshire and Vermont nor the United States recognized land claims or the tribal status of the Abenaki. The Cowasuck, now part of the Cowasuck Band of the Pennacook-Abenaki People, have filed numerous claims for ownership of parts of their old residential area. All have been rejected.

See also

- List of Native American peoples in the United States

External links

References

- Day, Gornon M. (April 1981). "Abenaki Place-Names in the Champlain Valley". International Journal of American Linguistics. University of Chicago Press. 47 (2): 144. JSTOR 1264435.

- "Cowass North AmericaIncorporated". New Hampshire Department of State. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- Roberts Clark, Patricia (Oct 21, 2009). Tribal Names of the Americas : Spelling Variants and Alternative Forms, Cross-Referenced. McFarland & Company. pp. 56, 73. ISBN 978-0786438334.

- "Tribal Information for Pilgrim Nuclear Power Station" (PDF). United STates Nuclear Regulatory Commission. April 10, 2006. p. 4. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- Roberts Clark, Patricia (Oct 21, 2009). Tribal Names of the Americas : Spelling Variants and Alternative Forms, Cross-Referenced. McFarland & Company. pp. 56, 73. ISBN 978-0786438334.

- Calloway, Colin G. (March 15, 1994). The Western Abenakis of Vermont, 1600-1800: War, Migration, and the Survival ofan Indian People. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 8. ISBN 0806125683.

- Mathewson III, R. Duncan (2011). "Western Abenaki of theUpper Connecticut River Basin:Preliminary Notes on Native AmericanPre-Contact Culture in Northern New England" (PDF). The Journal of Vermont Archaeology. 12: 7. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- Abrams, Marc D. (November 2001). "Eastern White Pine Versatility in the Presettlement Forest: This eastern giant exhibited vast ecological breadth in the original forest but has been on the decline with subsequent land-use changes". BioScience. 51 (11): 967. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0967:EWPVIT]2.0.CO;2.

- Dill, Jordan. "Abenaki History". Tolatsga. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- BELMESSOUS, Saliha (April 2005). "Assimilation and Racialism inSeventeenthandEighteenth-CenturyFrenchColonial Policy". American Historical Review. 110 (2). Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Sébastien Rasles (1833). Pickering, John (ed.). A Dictionary of the Abnaki Language, in North America. Retrieved 5 November 2019.