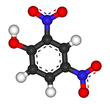

2,4-Dinitrophenol

2,4-Dinitrophenol (2,4-DNP or simply DNP) is an organic compound with the formula HOC6H3(NO2)2. It is a yellow, crystalline solid that has a sweet, musty odor. It sublimes, is volatile with steam, and is soluble in most organic solvents as well as aqueous alkaline solutions.[1] When in a dry form, it is a high explosive and has an instantaneous explosion hazard.[2] It is a precursor to other chemicals and is biochemically active, inhibiting adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production in cells with mitochondria. Its use as a dieting aid has been identified with severe side-effects, including a number of deaths.[3]

| |||

Sample of pure compound | |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

2,4-Dinitrophenol | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.080 | ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID |

|||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 0076 – Dry or wetted with less than 15% water. Class 1.1D explosives 1320 – Wetted with not less than 15% water. DT Solid desensitized explosives, toxic 1599 – Toxic solution | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C6H4N2O5 | |||

| Molar mass | 184.107 g·mol−1 | ||

| Density | 1.683 g/cm3 | ||

| Melting point | 108 °C (226 °F; 381 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 113 °C (235 °F; 386 K) | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | 4.114 | ||

| -73.1·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

| Hazards | |||

| Safety data sheet | International Chemical Safety Card 0464 | ||

| GHS pictograms |     | ||

| GHS Signal word | Danger | ||

GHS hazard statements |

H201, H300, H311, H331, H372, H400 | ||

| P261, P273, P280, P301+310, P311 | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| Infobox references | |||

Uses

Commercially, DNP is used as an antiseptic and as a non-selective bioaccumulating pesticide.[4]

DNP is particularly useful as a herbicide alongside other closely related dinitrophenol herbicides like 2,4-dinitro-o-cresol (DNOC), dinoseb and dinoterb.[5] Since 1998 DNP has been withdrawn from agricultural use.[6] Currently, there are no actively registered pesticides containing DNP in the United States or Europe.[7][8]

It is a chemical intermediate in the production of sulfur dyes,[9] wood preservatives[4] and picric acid.[10] DNP has also been used to make photographic developers and explosives (see shellite).[11] DNP is classified as an explosive in the United Kingdom[12] and the United States.[13]

Although DNP is widely considered too dangerous for clinical use, its mechanism of action remains under investigation as a potential approach for treating obesity.[14] As of 2015, research is being conducted on uncoupling proteins naturally found in humans.[15]

Biochemistry

In living cells, DNP acts as a proton ionophore, an agent that can shuttle protons (hydrogen cations) across biological membranes. It dissipates the proton gradient across mitochondria membranes, collapsing the proton motive force that the cell uses to produce most of its ATP chemical energy. Instead of producing ATP, the energy of the proton gradient is lost as heat.[3]

DNP is often used in biochemistry research to help explore the bioenergetics of chemiosmotic and other membrane transport processes.

Mechanism of action

DNP acts as a protonophore, allowing protons to leak across the inner mitochondrial membrane and thus bypass ATP synthase. This makes ATP energy production less efficient. In effect, part of the energy that is normally produced from cellular respiration is wasted as heat. The inefficiency is proportional to the dose of DNP that is taken. As the dose increases and energy production is made more inefficient, metabolic rate increases (and more fat is burned) in order to compensate for the inefficiency and to meet energy demands. DNP is probably the best known agent for uncoupling oxidative phosphorylation. The "phosphorylation" of adenosine diphosphate (ADP) by ATP synthase gets disconnected or "uncoupled" from oxidation.

From the Journal of Clinical Toxicology, Volume 44, Issue 3 (2006):

Dinitrophenol uncouples oxidative phosphorylation, causes release of calcium from mitochondrial stores and prevents calcium re-uptake. This leads to free intracellular calcium and causes muscle contraction and hyperthermia. Dantrolene inhibits calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum which reduces intracellular calcium. The resulting muscle relaxation allows heat dissipation. There is little risk to dantrolene administration. Since dantrolene may be effective in reducing hyperthermia caused by agents that inhibit oxidative phosphorylation, early administration may improve outcome.[16]

Pharmacokinetics

Information about pharmacokinetics of DNP in humans is limited.[17] The ATSDR's Toxicological Profile for Dinitrophenols remarks that DNP elimination appears to be rapid except when liver function is impaired.[18] The NEJM remarks that DNP appears to be eliminated in around three to four days, except possibly when the liver and kidneys are damaged.[19] Other papers give a wide array of possible half-lives, ranging from 3 hours[20] to 5–14 days,[21] while still other, more recent papers maintain that the half-life in humans is unknown.[22]

Hazards

Toxicity

DNP is considered to have high acute toxicity.[4] In March 2020 a UK judge stated "there is no antidote or remedy for DNP once taken. In consequence, DNP has a high mortality rate — of those who presented at hospital between 2007 and 2019 with a history of having taken DNP, 18% died. This puts DNP close to cyanide in terms of its toxicity."[23] Other than increasing metabolic rate, acute oral exposure to DNP has resulted in nausea, vomiting, sweating, dizziness, headache, and loss of weight.[4] Chronic oral exposure to DNP can lead to the formation of cataracts and skin lesions and has caused effects on the bone marrow, central nervous system, and cardiovascular system.[4][24] Contact with skin or inhalation can cause DNP poisoning. In 2009, an incident occurred in a Chinese chemical factory and 20 persons suffered acute DNP poisoning.[25]

The factor that limits ever-increasing doses of DNP is not a lack of ATP energy production, but rather an excessive rise in body temperature due to the heat produced during uncoupling. Accordingly, DNP overdose will cause fatal hyperthermia, with body temperature rising to as high as 43.1 °C (109.6 °F)[26] shortly before death. Case reports have shown that an acute administration of 10–20 milligrams per kilogram of body weight in humans can be lethal.[21][27][28][29][30] The lowest published fatal ingested dose is 4.3 mg/kg.[11][31] In the three separate publicly published medical management cases, a single dose of few tablets from an online retailer (tablet dose unknown) has proven fatal.[28][32][33]

The United Kingdom's Food Standards Agency identifies DNP as "an industrial chemical known to have serious short-term and long-term effects, which can be extremely dangerous to human health" and advises "consumers not to take any product containing DNP at any level. This chemical is not suitable for human consumption."[34] From December 2018 DNP has been classified as an "illegal poisonous substance" in Russia.[35][36]

Chemical hazards

A dust explosion is possible with DNP in powder or granular form in the presence of air. DNP may explosively decompose when submitted to shock, friction or concussion, and may explode upon heating.[37] DNP forms explosive salts with strong bases as well as ammonia, and emits toxic fumes of nitrogen dioxide when heated to decomposition.[38] DNP's explosive strength is 81% that of TNT, based on the Trauzl lead block test.[39] DNP was the cause of the 1916 Rainham Chemical Factory explosion which left 7 dead and 69 injured.[40][41] DNP is listed on the Homeland Security Anti-Terrorism Chemicals of Interest list.[42]

Synthesis

DNP is produced by hydrolysis of 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene.[9] Another route of DNP synthesis is by nitration of phenol with nitric acid.[43][44]

History and society

DNP was widely used in explosive mixtures around the world. Examples include Shellite in the UK, Tridite in the US, Tridita in Spain, MDPC/DD in France, MABT/MBT in Italy, and DNP in the USSR.[45] During World War I, 36 munition factory workers in France and 27 in the US lost their lives through DNP poisoning.[46]

Three fatalities were reported in dye factories, where DNP was used to make sulfur black dye.[47]

DNP was used extensively in diet pills from 1933 to 1938 after Cutting and Tainter at Stanford University made their first report on how the compound substantially increased metabolic rate.[48][49] This effect occurs via DNP acting as a proton ionophore. After only its first year on the market, Tainter estimated that at least 100,000 people had been treated with DNP in the United States, in addition to many others abroad.[50]

In light of the adverse effects and fatal hyperthermia caused by DNP when it was used clinically, the dose was slowly titrated according to personal tolerance, which varies greatly.[51] Concerns about dangerous side-effects and rapidly developing cataracts[52] resulted in DNP being discontinued in the United States by the end of 1938.[53] In 1938, the FDA included DNP in a list of drugs potentially so toxic that they should not be used even under a physician's supervision.[54]

"In studies of intermediate-duration oral exposure to 2,4-DNP, cases of death from agranulocytosis (described in the discussion of Hematological Effects) have been attributed to 2,4-DNP. These cases occurred during the usual dosing regimens for weight loss, employing increasing doses in one case from 2.9 to 4.3 mg/kg/day of 2,4-DNP for 6 weeks (Dameshek and Gargill 1934); a dose of 1.03 mg/kg/day 2,4-DNP for 46 days in another case (Goldman and Haber 1936); and in another, from 0.62 to 3.8 mg/kg/day 2,4-DNP as sodium 2,4-DNP for 41 days (Silver 1934). In all cases, the patients were under medical supervision."[55]

DNP, however, continues to be used by some bodybuilders and athletes to rapidly lose body fat. Fatal overdoses include cases of accidental exposure,[56] suicide,[21][22][57] and excessive intentional exposure (overdose).[22][58][59] The substance's use as a dieting aid has also led to a number of accidental fatalities,[58][60][61] including 26 confirmed DNP-related deaths in the UK since 2007.[62] Annual Reports of the American Association of Poison Control Centers identify 18 DNP poisoning fatalities between 2013 and 2018 in the US.[63] The Swedish Poisons Information Centre has reported three fatal DNP cases between June 2012 and May 2013. "Forensic analysis of DNP is not routinely performed so the true number of DNP deaths may be higher."[64] DNP may not be detected in post mortem blood samples.[32][65]

In 2003, a vendor of DNP was sentenced to five years in prison for mail fraud, with the FDA's OCI investigators having gathered evidence that the vendor's encapsulation of DNP was neither accurate nor sanitary. One of his customers died and another was hospitalized in a coma for more than 10 days.[66][67] In 2018, a seller in the United Kingdom was convicted of manslaughter for selling DNP as "fatburner" for human consumption. The conviction was sent to retrial in 2020 by the English Court of Appeal, where the seller was, once again, convicted of gross negligence manslaughter.[68][69][23] In 2019, a company selling DNP in the UK was found "guilty of placing an unsafe food product on the market" and fined £100,000. The director of the company was given a suspended prison sentence.[70] A seller in California was sentenced to three years in prison for selling DNP as diet pills.[71] In 2020, a man from North Carolina was sentenced to the maximum sentence of seven years in prison after three of his customers died from DNP poisoning.[72]

References

- Budavari, Susan; et al., eds. (1989). The Merck index : an encyclopedia of chemicals, drugs, and biologicals (11th ed.). Rahway, N.J.: Merck. pp. 1900. ISBN 978-0911910285. OCLC 21297020.

- "DINITROPHENOL, WETTED WITH NOT LESS THAN 15% WATER | CAMEO Chemicals | NOAA". cameochemicals.noaa.gov. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- Grundlingh J, Dargan PI, El-Zanfaly M, Wood DM (2011). "Summary of previously published fatalities relating to exposure to DNP including basic demographics, amount of exposure and maximal temperature recorded pre-death". J Med Toxicol. 7 (3): 205–12. doi:10.1007/s13181-011-0162-6. PMC 3550200. PMID 21739343.

- "2,4-Dinitrophenol" (PDF). Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- Gupta, Ramesh C., ed. (2011). Reproductive and developmental toxicology. London: Academic Press. p. 509. ISBN 9780123820327. OCLC 717387050.

- Pohanish, Richard P. (23 September 2011). Sittig's Handbook of Toxic and Hazardous Chemicals and Carcinogens. William Andrew. ISBN 9781437778700.

- https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/ToxProfiles/tp64.pdf

- Pohanish, Richard P. (6 September 2014). Sittig's Handbook of Pesticides and Agricultural Chemicals. William Andrew. ISBN 9781455731572.

- Gerald Booth "Nitro Compounds, Aromatic" in "Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry" 2007; Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a17_411

- Agrawal, Jai Prakash; Hodgson, Robert (11 January 2007). Organic Chemistry of Explosives. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470059357.

- Grundlingh, Johann; Dargan, Paul I.; El-Zanfaly, Marwa; Wood, David M. (September 2011). "2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP): a weight loss agent with significant acute toxicity and risk of death". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 7 (3): 205–212. doi:10.1007/s13181-011-0162-6. ISSN 1937-6995. PMC 3550200. PMID 21739343.

- Urben, Peter (18 March 2017). Bretherick's Handbook of Reactive Chemical Hazards. Elsevier. ISBN 9780081010594.

- "Commerce in Explosives; 2017 Annual List of Explosive Materials". Federal Register. 28 December 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- Harper JA, Dickinson K, Brand MD (2001). "Mitochondrial uncoupling as a target for drug development for the treatment of obesity". Obesity Reviews. 2 (4): 255–265. doi:10.1046/j.1467-789X.2001.00043.x. PMID 12119996.

- Busiello, Rosa A.; Savarese, Sabrina; Lombardi, Assunta (10 February 2015). "Mitochondrial uncoupling proteins and energy metabolism". Frontiers in Physiology. 6: 36. doi:10.3389/fphys.2015.00036. ISSN 1664-042X. PMC 4322621. PMID 25713540.

- Barker K, Seger D, Kumar S (2006). "Comment on "Pediatric fatality following ingestion of Dinitrophenol: postmortem identification of a 'dietary supplement'"". Clin Toxicol. 44 (3): 351. doi:10.1080/15563650600584709. PMID 16749560.

- "Ambient water quality criteria for nitrophenols, 440/5-80-063" (PDF). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 1980. Retrieved 9 June 2008.

- Harris, M. O.; Cocoran, J. J. (1995). "Toxicological Profile for Dinitrophenols". Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- Edsall, G. (1934). "Biological actions of dinitrophenol and related compounds: a review". The New England Journal of Medicine. 211 (9): 385–390. doi:10.1056/NEJM193408302110901.

- Korde AS, Pettigrew LC, Craddock SD, Maragos WF (September 2005). "The mitochondrial uncoupler 2,4-dinitrophenol attenuates tissue damage and improves mitochondrial homeostasis following transient focal cerebral ischemia". J. Neurochem. 94 (6): 1676–1684. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03328.x. PMID 16045446.

- Hsiao AL, Santucci KA, Seo-Mayer P, et al. (2005). "Pediatric fatality following ingestion of dinitrophenol: postmortem identification of a "dietary supplement"". Clin Toxicol. 43 (4): 281–285. doi:10.1081/clt-200058946. PMID 16035205.

- A. Hahn, K. Begemann, R. Burger, J. Hillebrand, H. Meyer, K. Preußner: "Cases of Poisoning Reported by Physicians in 2006", page 40. BfR Press and Public Relations Office, 2006.

- "R -v- Rebelo sentencing remarks" (PDF). Courts and Tribunals Judiciary. 11 March 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (1995). "Toxicological Profile for Dinitrophenols". Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Lu, Yuan-qiang; Jiang, Jiu-kun; Huang, Wei-dong (3 December 2011). "Clinical features and treatment in patients with acute 2,4-dinitrophenol poisoning". Journal of Zhejiang University Science B. 12 (3): 189–192. doi:10.1631/jzus.B1000265. ISSN 1673-1581. PMC 3048933. PMID 21370503.

- McGillis, Eric. "Page 83, '136. Rapid-onset hyperthermia and hypercapnea preceding rigor mortis and cardiopulmonary arrest in a DNP overdose'" (PDF). www.eapcct.org.

- Holborow, Alexander; Purnell, Richard M; Wong, Jenny Frederina (4 April 2016). "Beware the yellow slimming pill: fatal 2,4-dinitrophenol overdose". BMJ Case Reports. 2016: bcr2016214689. doi:10.1136/bcr-2016-214689. ISSN 1757-790X. PMC 4840695. PMID 27045052.

- "Dantrolene is not the answer to 2,4-dinitrophenol poisoning: more heated debate". ResearchGate. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- Veenendaal, A. van. "Surviving a life-threatening 2,4-DNP intoxication: 'Almost dying to be thin'". www.njmonline.nl.

- "Banned dinitrophenols still trigger both legal and forensic issues". ResearchGate. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- Bateman, Nick; Jefferson, Robert; Thomas, Simon; Thompson, John; Vale, Allister (26 June 2014). Oxford Desk Reference: Toxicology. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780191022487.

- "Page 1278, 'Case 377', American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC) - 2013 Annual Report". aapcc.org. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- Patankar, Aditi; Karnik, Niteen D.; Trivedi, Mayuri; Trivedi, Trupti; Aledort, Louis (13 July 2020). "Slim to Kill: 2,4-Dinitrophenol (DNP), The Naïve Assassin!". Clinical Case Reports International. 4 (1). ISSN 2638-4558.

- "Warning about 'fat-burner' substances containing DNP". Food Standards Agency. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ""Izvestia": the government has decided to withdraw from free trade in some anabolics – Russian Reality". Archived from the original on 30 December 2018. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- "О дополнении списка сильнодействующих и ядовитых веществ". government.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- Stellman, Jeanne Mager (1998). Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety: Guides, indexes, directory. International Labour Organization. ISBN 9789221098171.

- Sax, N.Irving; Bruce, Robert D (1989). Dangerous properties of industrial materials. 3 (7th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-442-27368-1.

- Meyer, Rudolf; Köhler, Josef; Homburg, Axel (9 May 2016). Explosives. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9783527689613.

- "Massive explosion that occurred at H.M. Factory, Rainham on 14th September 1916" (PDF).

- "Report ID 2136, Past Accident Review, The Institute of Explosives Engineers".

- "Appendix A: Chemicals of Interest". Department of Homeland Security. 6 July 2009. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- Khabarov, Yu. G.; Lakhmanov, D. E.; Kosyakov, D. S.; Ul'yanovskii, N. V. (1 October 2012). "Synthesis of 2,4-dinitrophenol". Russian Journal of Applied Chemistry. 85 (10): 1577–1580. doi:10.1134/S1070427212100163. ISSN 1608-3296.

- "Method for preparing 2,4-dinitrophenol by phenol sulfonation and nitration".

- Meyer, Rudolf; Köhler, Josef; Homburg, Axel (8 February 2008). Explosives. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9783527617036.

- "Provisional peer peviewed toxicity values for 2,4-dinitrophenol (CASRN 51-28-5)" (PDF). EPA.

- Hamilton, Alice (1921). Industrial Poisoning in Making Coal-tar Dyes and Dye Intermediates. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 25.

- Cutting WC, Mehrtens HG, Tainter ML (1933). "Actions and uses of dinitrophenol: Promising metabolic applications". J Am Med Assoc. 101 (3): 193–195. doi:10.1001/jama.1933.02740280013006.

- Tainter ML, Stockton AB, Cutting WC (1933). "Use of dinitrophenol in obesity and related conditions: a progress report". J Am Med Assoc. 101 (19): 1472–1475. doi:10.1001/jama.1933.02740440032009.

- Tainter ML, Cutting WC, Stockton AB (1934). "Use of Dinitrophenol in Nutritional Disorders: A Critical Survey of Clinical Results". Am J Public Health. 24 (10): 1045–1053. doi:10.2105/AJPH.24.10.1045. PMC 1558869. PMID 18014064.

- Simkins, S. (1937). "Dinitrophenol and desiccated thyroid in the treatment of obesity: a comprehensive clinical and laboratory study". J Am Med Assoc. 108: 2110–2117. doi:10.1001/jama.1937.02780250024006.

- Horner, WD (1941). "A Study of Dinitrophenol and Its Relation to Cataract Formation". Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 39: 405–37. PMC 1315023. PMID 16693262.

- Colman, Eric (July 2007). "Dinitrophenol and obesity: an early twentieth-century regulatory dilemma". Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 48 (2): 115–117. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2007.03.006. ISSN 0273-2300. PMID 17475379.

- FDA Consumer. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Food and Drug Administration. 1987.

- "ATSDR Toxicological Profile for Dinitrophenols, 2. HEALTH EFFECTS" (PDF). www.atsdr.cdc.gov.

- Leftwich RB, Floro JF, Neal RA, Wood AJ (February 1982). "Dinitrophenol poisoning: a diagnosis to consider in undiagnosed fever". South. Med. J. 75 (2): 182–184. doi:10.1097/00007611-198202000-00016. PMID 7058360.

- Bartlett J, Brunner M, Gough K (February 2010). "Deliberate poisoning with dinitrophenol (DNP): an unlicensed weight loss pill". Emerg Med J. 27 (2): 159–160. doi:10.1136/emj.2008.069401. PMID 20156878. S2CID 22319755.

- McFee RB, Caraccio TR, McGuigan MA, Reynolds SA, Bellanger P (2004). "Dying to be thin: a dinitrophenol related fatality". Veterinary and Human Toxicology. 46 (5): 251–254. PMID 15487646.

- Miranda EJ, McIntyre IM, Parker DR, Gary RD, Logan BK (2006). "Two deaths attributed to the use of 2,4-dinitrophenol". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 30 (3): 219–222. doi:10.1093/jat/30.3.219. PMID 16803658.

- "Dwudziestolatka zmarła po kuracji odchudzającej. Zażywała DNP" (in Polish). 7 June 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- "Chris Mapletoft parents 'shocked' over diet pills death". BBC News. 17 September 2013.

- "National Poisons Information Service Report 2018/19" (PDF).

- "American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC)". aapcc.org. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- "Page 422, 'The third lethal case over the last year with the weight loss agent 2,4-dinitrophenol'" (PDF). eapcct.org.

- Campos, Eduardo Geraldo de; Fogarty, Melissa; Martinis, Bruno Spinosa De; Logan, Barry Kerr (January 2020). "Analysis of 2,4-Dinitrophenol in Postmortem Blood and Urine by Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry: Method Development and Validation and Report of Three Fatalities in the United States". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 65 (1): 183–188. doi:10.1111/1556-4029.14154. ISSN 1556-4029. PMID 31430392.

- "Office of Criminal Investigation 2003". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 8 June 2015. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- Office of Regulatory Affairs (3 November 2018). "Court Sentencing(s) 2003". FDA.

- "Dinitrophenol ('DNP') and the Death of Eloise Parry" (PDF).

- "Eloise Parry: Man convicted over diet pill death".

- "FSA welcomes successful council prosecution". Food Standards Agency. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- "Sacramento Man Sentenced to 3 Years in Prison for Selling Fertilizer as a Fat-Burning Pill". US Department of Justice. 28 May 2019. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- "North Carolina Man Sentenced To 7 Years In Federal Prison For Selling Deadly Weight Loss Drug To Consumers". US Department of Justice. 6 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

Further reading

- "Food Standards Agency issues urgent advice on consumption of 'fat burner' capsules containing DNP" (Press release). Food Standards Agency. 17 June 2003. Retrieved 30 September 2007.

- "Warning about 'fat-burner' substances containing DNP" (Press release). Food Standards Agency. 1 November 2012.

External links

- "ToxFAQ about Dinitrophenols". Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. September 1996. Retrieved 17 July 2005.

- General 2,4-dinitrophenol information.

- CLH Report for 2,4-dinitrophenol – ECHA.

- Harmonised classification and labelling at EU level of 2,4-dinitrophenol

- Safety Data Sheet. Alfa Aesar Thermo Fisher Scientific Chemicals 2,4-Dinitrophenol SDS. August 2019. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- Toxicological Profile for Dinitrophenols 2019