1992 Landers earthquake

The 1992 Landers earthquake occurred on June 28 with an epicenter near the town of Landers, California.[4] The shock had a moment magnitude of 7.3 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of IX (Violent).

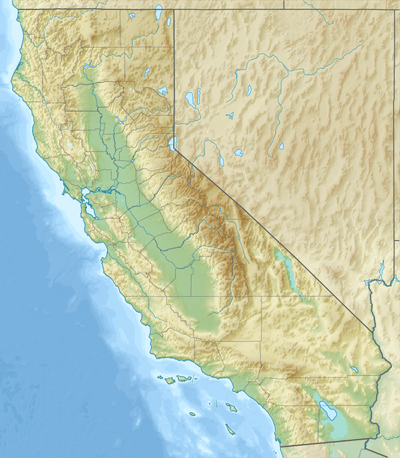

Palm Springs Los Angeles | |

| UTC time | 1992-06-28 11:57:35 |

|---|---|

| ISC event | 289086 |

| USGS-ANSS | ComCat |

| Local date | June 28, 1992 |

| Local time | 4:57:35 am PDT |

| Magnitude | 7.3 Mw |

| Depth | 0.68 miles (1.09 km) |

| Epicenter | 34.217°N 116.433°W[1] |

| Type | Strike-slip |

| Areas affected | Southern California United States |

| Total damage | $92 million [2] |

| Max. intensity | IX (Violent) |

| Foreshocks | 6.1 Mw April 23 at 4:51 [3] |

| Casualties | 3 killed 400+ injured |

Earthquake

At 4:57 a.m. local time (11:57 UTC) on June 28, 1992, a magnitude 7.3 earthquake awoke much of Southern California. Though it turned out it was not the so-called "Big One" as many people would think, it was still a very strong earthquake. The shaking lasted for two to three minutes. Although this earthquake was much more powerful than the 1994 Northridge earthquake, the damage and loss of life were minimized by its location in the sparsely-populated Mojave Desert.

The earthquake was a right-lateral strike-slip event, and involved the rupture of several different faults over a length of 75 to 85 km (47 to 53 mi).[4][5] The names of those that were involved are the Johnson Valley, Kickapoo (also known as Landers), Homestead Valley, Homestead/Emerson, Emerson Valley and Camp Rock faults.[4][5]

The surface rupture extended for 70 km (43 mi), with a maximum horizontal displacement of 5.5 m (18 ft) and a maximum vertical displacement of 1.8 m (5.9 ft).[6]

Damage

Damage to the area directly surrounding the epicenter was severe. Roads were buckled, buildings and chimneys collapsed. There were also large surface fissures. To the west in the Los Angeles Basin damage was much less severe. The majority of damage in the Los Angeles area involved items which had fallen off shelves. Unlike the 1994 Northridge earthquake nineteen and a half months later, no freeway bridges collapsed because of the epicenter's remote location. Electricity was cut to thousands of residents, but was generally restored within two to three hours. There was also some damage to homes from water displaced from swimming pools.

Loss of life in this earthquake was minimal. Two people died as a result of heart attacks, and a 3-year-old boy from Massachusetts, who was visiting Yucca Valley with his parents, died when bricks from a chimney collapsed into a living room where he was sleeping.[7] More than 400 people sustained injuries as a result of the earthquake.[2]

Related events

The quake was preceded by the 6.1 magnitude Joshua Tree earthquake at 4:51 on April 23, 1992 (UTC), which was south of the future Landers epicenter.[8][9] The 6.5 magnitude Big Bear earthquake, which hit about three hours after the Landers mainshock, was originally considered an aftershock. However, the United States Geological Survey determined that this was a separate, but related, earthquake. These two earthquakes are considered a regional earthquake sequence, rather than a main shock and aftershock.[10]

The 5.7 magnitude Little Skull Mountain (LSM) earthquake the following day, June 29, 1992, at 10:14 UTC near Yucca Mountain, Nevada, is also considered part of the regional sequence and may have been triggered by surface wave energy produced by the Landers earthquake. Foreshock activity, in the form of a significant increase in micro-earthquakes, was observed at Little Skull Mountain following the Landers earthquake, and the activity continued until the main LSM earthquake.[11]

Theories

The Landers earthquake and the other large quakes associated with it in the Mojave region have been attributed to two possible long-term trends. One of these is that the San Andreas Fault may be in the process of being replaced as the plate boundary (between the North American Plate and the Pacific Plate) by a new trend across the Mojave and east of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. The other is that these quakes were a manifestation of the propagation of rifting coming up from the Gulf of California.[12] Research is ongoing.

See also

References

- "Landers Earthquake". Southern California Earthquake Data Center. Archived from the original on March 5, 2014. Retrieved August 15, 2014.

- USGS. "M7.3 – Southern California". United States Geological Survey.

- Hauksson, E.; Jones, L. M.; Hutton, K.; Eberhart-Phillips, D. (1993). "The 1992 Landers Earthquake Sequence: Seismological observations" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 98 (B11): 19835–19858. Bibcode:1993JGR....9819835H. doi:10.1029/93jb02384.

- "Landers Earthquake". Southern California Earthquake Data Center. Archived from the original on October 25, 2007. Retrieved November 4, 2007.

- Sébastien Leprince; François Ayoub; Yann Klinger; Jean-Philippe Avouac (July 2007). Co-Registration of Optically Sensed Images and Correlation (COSI-Corr): an Operational Methodology for Ground Deformation Measurements (PDF). Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, 2007. IGARSS 2007. IEEE International. pp. 1943–1946. doi:10.1109/IGARSS.2007.4423207. ISBN 978-1-4244-1211-2.

- "Comments for the Significant Earthquake". National Geophysical Data Center. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- Gebe Martinez (June 30, 1992). "The Landers and Big Bear Quakes : Death of Toddler Touches Many in Close-Knit Town". Los Angeles Times.

- The 1992 Landers Earthquake Sequence: Seismological Observations

- Boyer, Edward J.; Reich, Kenneth (April 23, 1992). "6.1 Quake Felt in Wide Area of Southland". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- "El Salvador". Earthquake Report. USGS Earthquake Hazards Program. Retrieved October 10, 2008.

- Smith, K. D. (2001). "The 1992 Little Skull Mountain Earthquake Sequence, Southern Nevada Test Site" (PDF). Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 91 (6): 1595–1606. Bibcode:2001BuSSA..91.1595S. doi:10.1785/0120000089.

- LaMacchia, Diane (July 17, 1992). "Yucca Valley earthquake surprised experts". Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved November 4, 2007.

Further reading

- Berryman, K. (1992), "Reconnaissance field investigation of the Landers earthquake (Ms 7.5) of June 28, 1992, San Bernadino County, California, USA" (PDF), Bulletin of the New Zealand Society for Earthquake Engineering, 25 (3): 230–241, doi:10.5459/bnzsee.25.3.230-241

- Rymer, M. J. (2000), "Triggered Surface Slips in the Coachella Valley Area Associated with the 1992 Joshua Tree and Landers, California, Earthquakes", Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 90 (4): 832–848, Bibcode:2000BuSSA..90..832R, doi:10.1785/0119980130

External links

- Landers Earthquake at the Southern California Earthquake Data Center

- Big Bear Earthquake at the Southern California Earthquake Data Center

- Studying the M7.3 1992 Landers, California earthquake: original forms and initial modifications – Ramon Arrowsmith

- The International Seismological Centre has a bibliography and/or authoritative data for this event.