2002 Denali earthquake

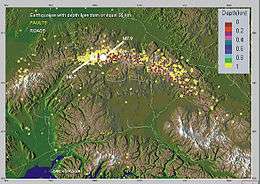

The 2002 Denali earthquake occurred at 22:12:41 UTC (1:12 PM Local Time) November 3 with an epicenter 66 km ESE of Denali National Park, Alaska, United States. This 7.9 Mw earthquake was the largest recorded in the United States in 37 years (after the 1965 Rat Islands earthquake). The shock was the strongest ever recorded in the interior of Alaska.[4] Due to the remote location, there were no fatalities and only a few injuries.

| |

Anchorage | |

| UTC time | 2002-11-03 22:12:41 |

|---|---|

| ISC event | 6123395 |

| USGS-ANSS | ComCat |

| Local date | November 3, 2002 |

| Local time | 13:12 |

| Magnitude | 7.9 Mw [1] |

| Depth | 13 km (8 mi) [1] |

| Epicenter | 63.51°N 147.6°W [1] |

| Fault | Denali Fault, Totschunda Fault |

| Type | Strike-slip |

| Total damage | $20–56 million [2][3] |

| Max. intensity | IX (Violent) [3] |

| Casualties | One injured [2] |

Due to the shallow depth, it was felt at least as far away as Seattle and it generated seiches on bodies of water as far away as Texas and New Orleans, Louisiana.[5] About 20 houseboats were damaged by a seiche on a lake in Washington State.[5]

Tectonic setting

The Denali-Totschunda fault is a major dextral (right lateral) strike-slip system, similar in scale to the San Andreas fault system. In Alaska, moving from east to west, the plate interactions change from a transform boundary between Pacific and North American plates to a collision zone with a microplate, the Yakutat terrane, which is in the process of being accreted to the North American plate, to a destructive boundary along the line of the Aleutian islands. The Denali-Totschunda fault system is one of the structures that accommodate the accretion of the Yakutat terrane.

Earthquake characteristics

On October 23, 2002, there was a magnitude 6.7 earthquake located on the Denali fault. Because of its location close to the November 3 event and the fact that it preceded it by only 11 days, this earthquake is regarded as a foreshock that probably directly triggered the main shock.

The initial rupture on November 3 was on a thrust fault segment, the previously unknown Susitna Glacier thrust,[6][7] to the south of the Denali fault. The epicenter lies just 25 kilometers (16 mi) east of the October 23 foreshock. The rupture then jumped to the main Denali Fault strand propagating for a further 220 km (137 mi) before jumping again onto the Totschunda Fault and rupturing another 70 km (43 mi) of fault plane.[7] The total surface rupture was ca. 340 km (211 mi).

There is evidence of local supershear propagation inferred from ground motions.[8]

Earthquake damage

Minor damage was reported over a wide area but the only examples of severe damage were on highways that crossed the fault trace and areas that suffered liquefaction, e.g. Northway Airport.[9] Several bridges were damaged but none so severely that they were closed to traffic.

Due to the general self-sufficiency of those living near the fault rupture, very few lifeline systems were compromised. These people tend to get water from private wells, heat their homes and cook their meals with gas furnaces and stoves, and maintain individual septic systems.[9]

The Trans-Alaska Pipeline System crosses the rupture trace; the pipeline suffered some minor damage to supports. There was no oil spillage, as the pipeline at that location was designed to move laterally along beams to withstand major movement on the Denali Fault.[10] The pipeline was shut down for three days to allow for inspections but was then reopened.

See also

References

- ISC (2016), ISC-GEM Global Instrumental Earthquake Catalogue (1900–2012), Version 3.0, International Seismological Centre

- USGS (September 4, 2009), PAGER-CAT Earthquake Catalog, Version 2008_06.1, United States Geological Survey

- National Geophysical Data Center / World Data Service (NGDC/WDS) (1972), Significant Earthquake Database (Data Set), National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA, doi:10.7289/V5TD9V7K

- Fuis, Gary S.; Wald, Lisa A. (February 5, 2003). "Fact Sheet 014-03: Rupture in South-Central Alaska—The Denali Fault Earthquake of 2002". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-02-17. Retrieved 2014-09-18.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Crone,A.J., Personius,S.F., Craw,P.A., Haeussler,P.J. & Staft,L,.A. 2004.The Susitna Glacier Thrust Fault: Characteristics of Surface Ruptures on the Fault that Initiated the 2002 Denali Fault Earthquake. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America; v. 94; p. S5-S22.

- "2002 Denali Fault Earthquake". Science.

- Dunham, E. M.; Archuleta, R. J. (2004), "Evidence for a Supershear Transient during the 2002 Denali Fault Earthquake", Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 94 (68): 256–268, Bibcode:2004BuSSA..94S.256D, doi:10.1785/0120040616

- Mark Yashinsky, ed. (2004). Denali, Alaska, Earthquake of November 3, 2002. Reston, VA: ASCE, TCLEE. ISBN 9780784407479. Archived from the original on 2013-12-31.

- Sorensen, S.P. and Meyer, K.J.: Effect of the Denali Fault Rupture on the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Archived 2011-05-14 at the Wayback Machine; Sixth U.S. Conference and Workshop on Lifeline Earthquake Engineering, ASCE, August 2003.

External links

- The 2002 Denali Fault earthquake – United States Geological Survey

- M 7.9 Denali Fault earthquake of November 3, 2002 – Alaska Earthquake Center

- The International Seismological Centre has a bibliography and/or authoritative data for this event.