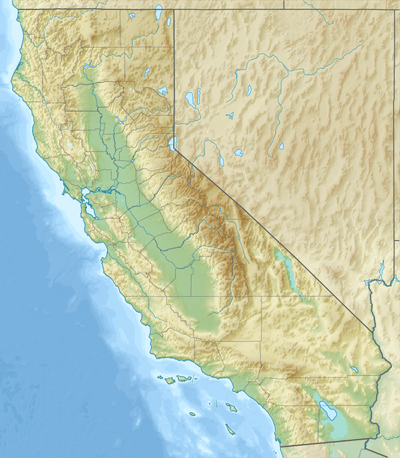

1979 Imperial Valley earthquake

The 1979 Imperial Valley earthquake occurred at 16:16 Pacific Daylight Time (23:16 UTC) on 15 October just south of the Mexico–United States border. It affected Imperial Valley in Southern California and Mexicali Valley in northern Baja California. The earthquake had a relatively shallow hypocenter and caused property damage in the United States estimated at US$30 million. The irrigation systems in the Imperial Valley were badly affected, but no deaths occurred. It was the largest earthquake to occur in the contiguous United States since the 1971 San Fernando earthquake eight years earlier.

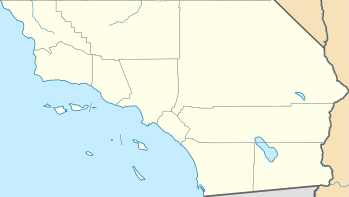

Ridgecrest Pasadena Las Vegas San Diego | |

| UTC time | 1979-10-15 23:16:54 |

|---|---|

| ISC event | 657282 |

| USGS-ANSS | ComCat |

| Local date | 15 October 1979 |

| Local time | 16:16 UTC |

| Duration | 5–13 seconds[1] |

| Magnitude | 6.5 Mw(GCMT) [2] |

| Depth | 11.6 km (7.2 mi)[3] |

| Epicenter | 32°37′N 115°19′W |

| Type | Strike-slip |

| Areas affected | Baja California (Mexico) Southern California (United States) |

| Total damage | US$30 million[4] |

| Max. intensity | IX (Violent)[5] |

| Peak acceleration | 1.74g[6] |

| Aftershocks | 5.8 ML 16 October at 6:59[7] |

| Casualties | 91 injured, no deaths[4] |

The earthquake was 6.5 on the Mw scale, with a maximum perceived intensity of IX (Violent) on the Mercalli intensity scale. However, most of the intensity measurements were consistent with an overall maximum intensity of VII (Very strong), and only the damage to a single structure, the Imperial County Services building in El Centro, was judged to be of intensity IX. Several comprehensive studies on the total structural failure of this building were conducted with a focus on how the building responded to the earthquake's vibration. It was one of the first heavily instrumented office buildings to be severely damaged by seismic forces.

The Imperial Valley is surrounded by a number of interconnected fault systems and is vulnerable to both moderate and strong earthquakes as well as earthquake swarms. The area was equipped with an array of strong motion seismographs for analyzing the fault mechanisms of nearby earthquakes and seismic characteristics of the sediments in the valley. The earthquake was significant in the scientific community for studies of both fault mechanics and repeat events. Four of the region's known strike-slip faults and one additional newly discovered normal fault all broke the surface during the earthquake.

Tectonic setting

The Salton Trough is part of the complex plate boundary between the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate where it undergoes a transition from the continental transform of the San Andreas Fault system to the series of short spreading centers of the East Pacific Rise linked by oceanic transforms in the Gulf of California. The two main right–lateral strike-slip fault strands that extend across the southern part of the trough are the Elsinore Fault Zone/Laguna Salada Fault to the western side of the trough and the Imperial Fault to the east.[8] The Imperial Fault is linked to the San Andreas Fault through the Brawley Seismic Zone, which is a spreading center beneath the southern end of the Salton Sea.

With the San Jacinto Fault Zone to the northwest, the Elsinore fault to the south-southwest, and the Imperial fault centered directly under the Imperial Valley, the area frequently encounters seismic activity, including moderate and damaging earthquakes. Other events in 1852, 1892, 1915, 1940, 1942, and 1987 have impacted the region.[9] More small to moderate events of less than 6.0 (local magnitude) have occurred in this area than any other section of the San Andreas fault system.[10]

Earthquake

The earthquake was caused by rupture along parts of the Imperial Fault, the Brawley fault zone and the Rico Fault, a previously unknown normal fault near Holtville, though slip was also observed on the Superstition Hills Fault and the San Andreas Fault. The maximum observed right lateral displacement on the Imperial fault—measured within the first day of the event to the northwest of the epicenter—was 55–60 cm (22–24 in), but measurements taken five months following the earthquake closer to the southeast end of the rupture showed there was an additional 29 cm (11 in) of postseismic slip (for a total slip of 78 cm (31 in). Several strands of the Brawley fault zone, to the east of the Imperial fault, ruptured intermittently along a length of 11.1 km (6.9 mi), and just one kilometer of the Rico fault slipped with a maximum vertical displacement of 20 cm (7.9 in) (no horizontal slip was observed on that fault).[11]

The pattern of displacement along the Imperial Fault was very similar to that observed for the northern part of the rupture during the 1940 El Centro earthquake, although on this occasion the rupture did not extend across the border into Mexico. This had been explained as the behavior of individual slip patches along the Imperial Fault with two patches rupturing in 1940 and only the northern one in 1979.[12] The faulting that gave rise to the earthquake has been modeled by comparing synthetic seismograms with near-source strong motion recordings. This analysis showed that the rupture speed had at times exceeded the shear wave velocity,[13] making this the first earthquake for which supershear rupture was inferred.[14]

The United States Geological Survey operates a series of strong motion stations in the Imperial Valley and while the majority of stations in the array recorded ground accelerations that were not unexpected, station number six registered an unusually high vertical component reading of 1.74g which, at the time, was the highest yet recorded as the result of an earthquake. One explanation of the anomaly attributed the amplification to path effects and a separate theory put forth described supershear effects that generated a focused pulse directly at the station. A later proposal stated that both multipath and focusing effects due to a "lens like effect" produced by a sedimentary wedge at the junction of the Imperial and Brawley faults (under the station) may have been the cause of the high reading.[6]

Damage

The earthquake caused damage to the Californian cities of El Centro and Brawley, and in the Mexican city of Mexicali Mexico. There were injuries from the quake on both sides of the border. The state Office of Emergency Preparedness declared 61 injuries on the American side and police claimed that 30 were injured in Mexico. The Red Cross stated that cuts from broken glass, bruises from falling objects, and a few broken bones were reported. California's Interstate 8 developed cracks in it, but vehicles were still able to traverse the highway. The California Highway Patrol warned drivers that use of the road would be at their own risk.[15]

Damage to the roadways was heavier farther north on California State Route 86 where settling of the road by as much as four to six inches occurred, and a bridge separation closed the highway west of Brawley. Governor Jerry Brown ended a presidential campaign trip through New England early in order to return to the Imperial Valley and declare a state of emergency there. Two fires occurred in El Centro with the loss of a trailer being reported, though fire was avoided near the Imperial County Airport when a 60,000 barrel gasoline tank farm was seriously damaged and was losing 50 US gallons (190 l; 42 imp gal) a minute. Firefighters drained the tanks and replaced the fuel with water to avoid the gasoline vapor from causing a hazard.[16]

The earthquake shaking also led to extensive damage to the irrigation systems of the Imperial Valley, leading to breaches in some canals, particularly the All-American Canal that brings water to the valley from the Colorado River. A 13 km (8.1 mi) section of the unlined canal between the Ash and East Highline canals experienced settling. The Imperial Irrigation District estimated damage to be $982,000 for the three canals. Water flow was immediately reduced to prevent further damage and to allow assessments to be made, and within four days the repairs had been completed and full capacity restored. A hydraulic gate and a concrete facility that were damaged during the May 1940 earthquake needed repair again. The 1940 event caused significant destruction to canals on both sides of the international border, with 108 km (67 mi) of damage along eight canals on the US side alone.[17]

Imperial County Services building

The Imperial County Services building, a six-story reinforced concrete building located 29 km (18 mi) northwest of the epicenter in El Centro, was built in 1971 when there were few other tall buildings in the area. The decision to equip the building with nine strong motion sensors in May 1976 was based on its size, structural attributes, and location in a seismically active area.[18] Unusually detailed structural analysis was possible as a result of the building having been outfitted with the instrumentation. The initial configuration was tested shortly after its installation when a relatively small (4.9 local magnitude) earthquake occurred 32 km (20 mi) northwest of the building on 4 November 1976. The accelerations recorded on the equipment during the event proved to be of very low amplitude and, as a result, the instrumentation was upgraded to include a 13 channel configuration in the building along with a Kinemetrics triaxial (3 channel) accelerograph located 340 ft (100 m) east of the building at ground level. The full 16 channel system was managed by the California Division of Mines and Geology Office of Ground Motion Studies and provided almost 60 seconds worth of high resolution data during the 1979 event.[19]

In an interview with the Los Angeles Times following the earthquake, Fritz Matthiesen, a scientist with the United States Geological Survey, said that the instruments captured "about the third or fourth most significant recording of building damage we've made in 40 years" and that they "have only three other cases in which damage has occurred in an instrumented building".[15]

Several types of irregular construction styles were incorporated into the building that contributed to its mass and strength not being uniform throughout the structure. These differences in strength allowed damage to be concentrated in one or more areas rather than being distributed equally and reduced the building's ability to sustain the tremors. Two of the irregularities of the building were the end shear walls that stopped below the second floor and the first floor carrying its load via square support columns. The result of the design was that the first floor was less stiff than the upper floors, and during the earthquake the building sustained uneven damage distribution, a condition that may have led to the complete collapse of the building in a larger earthquake. Because of its failure at the foundation and first floor level, the building was considered a total loss and was ultimately demolished.[20]

| Selected Mercalli intensities | ||

| MMI | Locations | |

|---|---|---|

| IX (Violent) | Imperial County Services Building | |

| VII (Very Strong) | Brawley, Calexico | |

| VI (Strong) | Yuma, Holtville | |

| V (Moderate) | San Diego | |

| IV (Light) | Ridgecrest, Las Vegas | |

| III (Weak) | Pasadena | |

| Stover & von Hake 1984, pp. 41–50 | ||

Intensity

While the most extreme demonstration of the earthquake's intensity was at the Imperial County Services Building, the shock was felt over an area of roughly 128,000 square miles. A more precise estimate was not possible due to the boundaries of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean. At numerous department stores and the fire station in Brawley, a collapsed brick wall, cracked concrete fixtures, and ceiling or roof damage was consistent with intensity VII shaking. Similar effects were also reported across the border in Calexico. Intensity VI effects were observed in Heber, Holtville, and Yuma, Arizona.[21]

Aftershocks

An early study of the event encompassed more than 2,000 aftershocks (and included four of magnitude 5.0 or greater) that were recorded within 20 days of the mainshock, with the area south of the border near the epicenter remaining relatively quiet. Most of the aftershock activity was within 15 kilometers (9.3 mi) of Brawley (especially the first eight hours after the mainshock), although they occurred from the Salton Sea in the north to the Cerro Prieto Geothermal Power Station to the south, a distance of 110 kilometers (68 mi). The first strong aftershock (5.0) occurred at 23:19 GMT just 2.5 minutes after the mainshock and the strongest aftershock (5.8) occurred at 6:58 GMT on 16 October west of Brawley.[22]

While the focal mechanism of the mainshock was right-lateral fault slip on the northwest trending Imperial fault, a marked change in the distribution of aftershocks occurred with the onset of the Brawley aftershock, which exhibited left-lateral slip. A distinct zone of aftershocks formed a belt from west of Brawley to near Wiest Lake, where sinistral motion on a northeast trending conjugate fault responded to an increase in tension at the northwest end of the Imperial fault. Another line of aftershocks along the projection of the southern San Andreas fault extended south into the valley up to 50 km (31 mi). Activity in that area of the valley had been aseismic through 1978, and a few events occurred just prior to the event, and a significant increase in the amount of activity followed the mainshock.[22]

Ground disturbances

During two outings in late 1979 and early 1980 several researchers (including Thomas H. Heaton and John G. Anderson) examined the region near the New River and discovered ground disturbances that were related to the Brawley aftershock. Along the banks of the river the seismologists discovered sand boils, a newly formed pond, and an extension crack that was found to run 10 km (6.2 mi) near the south bank in an irregular and disconnected fashion from Brawley to Wiest lake. It was later discovered that the Brawley earthquake had an aftershock zone that matched the area of the disturbances. Accelerograms recorded from the nearby Del Rio Country Club also showed "clear and impressive evidence" of near field ground motions, which may have indicated nearby primary faulting.[23]

Numerous sites running along the New River were examined including the twin reinforced concrete bridges in Brawley. Slumping of the foundations there resulted in severe damage, and occurred as a result of the 15 October main shock, though the Brawley earthquake's epicenter was nearby. At the Imperial County Dump, several instances of ground failure were observed in sedimentary deposits near the top of and parallel to the river bank, and other cracks were found in that area that were determined to be the result of differential settling. Farther north at the entrance to the Del Rio Country Club, 30 cm (12 in) scarplets were located west of Route 111, but undisturbed Pleistocene sedimentary layers likely indicated that the scarps were the result of local slumping in the roadcut and not the result of surface faulting. A large pond had apparently formed near the KROP radio station's antenna site where profound liquefaction and subsidence occurred in the river valley. Two weeks following the earthquake sand boils at the same location were still discharging water.[23]

References

- Youd & Wieczorek 1982, p. 223

- ISC-EHB Event 657282 [IRIS].

- ISC-EHB Event 657282 [IRIS].

- Stover, C.W.; Coffman, J.L. (1993). Seismicity of the United States, 1568–1989 (Revised). U.S. Geological Survey professional paper 1527. United States Government Printing Office. p. 166.

- Reagor, B.G.; Stover, C.W.; Algermissen, S.T.; Steinbrugge, K.V.; Hubiak, P.; Hopper, M.G.; Marnhard, L.M. (1982), "Preliminary evaluation of the distribution of seismic intensities", The Imperial Valley, California, Earthquake of October 15, 1979, Geological Survey professional paper 1254, United States Government Printing Office, p. 255

- Rial, J.A.; Pereyra, V.; Wojcik, G.L. (1986). "An explanation for USGS Station 6 record, 1979 Imperial Valley earthquake: a caustic induced by a sedimentary wedge" (PDF). Geophysical Journal. 84 (2): 257–258, 270, 277. Bibcode:1986GeoJ...84..257R. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.1986.tb04356.x.

- Heaton, Anderson & German 1983, pp. 1161, 1166

- Mueller, K.J.; Rockwell T.K. (1995). "Late quaternary activity of the Laguna Salada fault in northern Baja California, Mexico". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 107 (1): 8–18. Bibcode:1995GSAB..107....8M. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1995)107<0008:LQAOTL>2.3.CO;2.

- "Historic Imperial County earthquakes". Archived from the original on 7 July 2012.

- Pauschke et al. 1981, p. 1

- Sharp, R.V.; Lienkaemper, J.J.; Bonilla, M.G.; Burke, D.B.; Fox B.F.; Herd D.G.; Miller D.M.; Morton D.M.; Ponti D.J.; Rymer M.J.; Tinsley J.C.; Yount J.C.; Kahle J.E.; Hart E.W. & Sieh K. (1982). "Surface faulting in the central Imperial Valley". The Imperial Valley, California, Earthquake of October 15, 1979. Geological Survey professional paper 1254. United States Government Printing Office. pp. 119, 120.

- Sieh, K. (1996). "The repetition of large-earthquake ruptures". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 93 (9): 3764–3771. Bibcode:1996PNAS...93.3764S. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.9.3764. PMC 39434. PMID 11607662.

- Archuleta, R.J. (1984). "A Faulting Model for the 1979 Imperial Valley Earthquake". Journal of Geophysical Research. 89 (B6): 4559–4585. Bibcode:1984JGR....89.4559A. doi:10.1029/JB089iB06p04559.

- Bouchon, M.; Karabulut H.; Bouin M.-P.; Schmittbul J.; Vallée M.; Archuleta R.; Das S.; Renard F. & Marsan D. (2010). "Faulting characteristics of supershear earthquakes" (PDF). Tectonophysics. 493 (3–4): 244–253. Bibcode:2010Tectp.493..244B. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2010.06.011.

- Meyer, Richard E. (17 October 1979), "Aid for Quake Victims Sought; Emergency proclaimed by Brown", Los Angeles Times

- West, Richard (16 October 1979), "6.4 Quake Jolts Southland; 91 Hurt, Buildings Heavily Damaged in Border Area", Los Angeles Times

- Youd & Wieczorek 1982, pp. 235, 237

- Pauschke et al. 1981, p. 7

- Pauschke et al. 1981, p. 10

- NIBS (December 2010). "Earthquake-Resistant Design Concepts—An Introduction to the NEHRP Recommended Seismic Provisions for New Buildings and Other Structures". National Institute of Building Sciences Building Seismic Safety Council. pp. 38–39.

- Stover, C. W.; von Hake, C. A. (1984), United States earthquakes, 1979, Open-File report 84-979, United States Government Printing Office, pp. 41–50, Bibcode:1981use..rept.....S

- Johnson, C.E; Hutton, L.K. (1982), "Aftershocks and preearthquake seismicity", The Imperial Valley, California, Earthquake of October 15, 1979, Geological Survey professional paper 1254, United States Government Printing Office, pp. 59–63

- Heaton, T. H.; Anderson, J. G.; German, P. T. (1983), "Ground Failure Along the New River Caused by the October 1979 Imperial Valley Earthquake Sequence", Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, Seismological Society of America, 73 (4): 1161–1163

Sources

- ANSS, "Imperial Valley 1979: M 6.4 – 10 km E of Mexicali, B.C., MX", Comprehensive Catalog, U.S. Geological Survey .

- International Seismological Centre, ISC-EHB Bulletin, Thatcham, United Kingdom, http://www.isc.ac.uk/ .

- Pauschke, J. M.; Oliveira, C. S.; Shah, H. C.; Zsutty, T. C. (1981), A Preliminary Investigation of the Dynamic Response of the Imperial County Services Buildings During the October 15, 1979 Imperial Valley Earthquake (PDF), Stanford University Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, archived from the original (PDF) on 11 December 2013

- Youd, T.L.; Wieczorek, G.F. (1982), "Liquefaction and secondary ground failure", The Imperial Valley, California, Earthquake of October 15, 1979, Geological Survey professional paper 1254, United States Government Printing Office

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 1979 Imperial Valley earthquake. |

- Imperial Valley Earthquake – Southern California Earthquake Data Center

- Significant Earthquake – National Geophysical Data Center

- The International Seismological Centre has a bibliography and/or authoritative data for this event.