Sinistral and dextral

Sinistral and dextral, in some scientific fields, are the two types of chirality ("handedness") or relative direction. The terms are derived from the Latin words for "left" (sinister) and "right" (dexter). Other disciplines use different terms (such as dextro- and laevo-rotary in chemistry, or clockwise and anticlockwise in physics) or simply use left and right (as in anatomy).

Relative direction and chirality are distinct concepts. Relative direction is from the point of view of the observer; a completely symmetrical object has a left side and a right side, from the observer's point of view, if the top and bottom and direction of observation are defined. Chirality, however, is observer-independent: no matter how one looks at a right-hand screw thread, it remains different from a left-hand screw thread. Therefore, a symmetrical object has sinistral and dextral directions arbitrarily defined by the position of the observer, while an asymmetrical object that shows chirality may have sinistral and dextral directions defined by characteristics of the object, regardless of the position of the observer.

Biology

Right: The normally dextral (right-handed) shell of Neptunea despecta, a similar species found mainly in the Southern Hemisphere.

Gastropods

Because the coiled shells of gastropods are asymmetrical, they possess a quality called chirality–the "handedness" of an asymmetrical structure.

Over 90%[1] of gastropod species have shells in which the direction of the coil is dextral (right-handed). A small minority of species and genera have shells in which the coils are almost always sinistral (left-handed). A very few species show an even mixture of dextral and sinistral individuals (for example, Amphidromus perversus).[2]

Flatfish

The most obvious characteristic of flatfish, other than their flatness, is their asymmetrical morphology: both eyes are on the same side of the head in the adult fish. In some families of flatfish, the eyes are always on the right side of the body (dextral or right-eyed flatfish), and in others, they are always on the left (sinistral or left-eyed flatfish). Primitive spiny turbots include equal numbers of right- and left-sided individuals, and are generally more symmetrical than other families.[3]

Geology

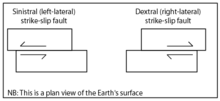

In geology, the terms sinistral and dextral refer to the horizontal component of movement of blocks on either side of a fault or the sense of movement within a shear zone. These are terms of relative direction, as the movement of the blocks are described relative to each other when viewed from above. Movement is sinistral (left-handed) if the block on the other side of the fault moves to the left, or if straddling the fault the left side moves toward the observer. Movement is dextral (right-handed) if the block on the other side of the fault moves to the right, or if straddling the fault the right side moves toward the observer.[4]

See also

- Dexter and sinister, as used in heraldry

- Helicity (disambiguation)

- Jeremy (snail)

- Laterality

- Left and right (disambiguation)

- Symmetry

Notes

- Schilthuizen M. & Davison A. (2005). "The convoluted evolution of snail chirality". Naturwissenschaften 92(11): 504–515. doi:10.1007/s00114-005-0045-2.

- Amphidromus perversus (Linnaeus, 1758).

- Chapleau, Francois & Amaoka, Kunio (1998). Paxton, J.R. & Eschmeyer, W.N. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Fishes. San Diego: Academic Press. xxx. ISBN 0-12-547665-5.

- Park, R.G. (2004). Foundation of Structural Geology (3 ed.). Routledge. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-7487-5802-9.