Hurricane Cindy (1959)

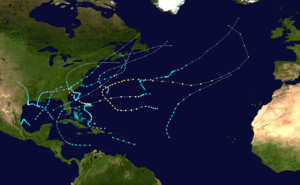

Hurricane Cindy impacted the Carolinas, the Mid-Atlantic states, New England, and the Canadian Maritime Provinces during the 1959 Atlantic hurricane season. The third storm of the season, Cindy originated from a low-pressure area associated with a cold front located east of northern Florida. The low developed into a tropical depression on July 5 while tracking north-northeastward, and became Tropical Storm Cindy by the next day. Cindy turned westward because of a high-pressure area positioned to its north, and further intensified into a weak hurricane off the coast of the Carolinas on July 8. Early on July 9, Cindy made landfall near McClellanville, South Carolina, and re-curved to the northeast along the Fall Line as a tropical depression. It re-entered the Atlantic on July 10, quickly restrengthening into a tropical storm while it began to move faster. On July 11, Cindy passed over Cape Cod, while several other weather systems helped the storm maintain its intensity. Cindy transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on July 12 as it neared the Canadian Maritime Provinces.

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

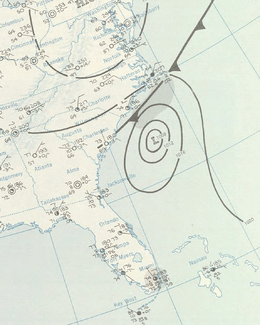

A daily weather map for July 8, 1959, depicting Hurricane Cindy approaching South Carolina | |

| Formed | July 5, 1959 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | July 11, 1959 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 75 mph (120 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 996 mbar (hPa); 29.41 inHg |

| Fatalities | 1 direct, 5 indirect |

| Damage | $75,000 (1959 USD) |

| Areas affected | The Carolinas, Mid-Atlantic, New England, Canadian Maritime Provinces |

| Part of the 1959 Atlantic hurricane season | |

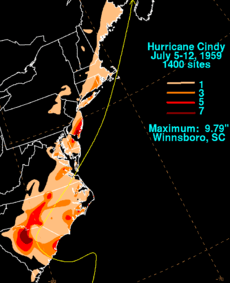

Overall structural damage from Cindy was minimal. One driver was killed in Georgetown, South Carolina after colliding with a fallen tree, and five indirect deaths were caused by poor road conditions wrought by the storm in New England. Many areas experienced heavy rains, and several thousand people evacuated. Other than broken tree limbs, shattered windows and power outages, little damage occurred. Cindy brought a total of eleven tornadoes with it, of which two caused minor damage in North Carolina. The heaviest rainfall occurred in north central South Carolina, where rainfall amounted to 9.79 inches (249 mm). Tides ranged from 1 to 4 feet (0.30 to 1.22 m) above normal along the coast. As drought-like conditions were present in the Carolinas at the time, the rainfall produced by Hurricane Cindy in the area was beneficial. After becoming extratropical over the Canadian Maritimes, the cyclone produced heavy rains and strong winds that sunk one ship. Damage caused by Cindy was estimated at $75,000 (1959 USD).

Meteorological history

The origins of Cindy can be attributed to a deepening low-pressure area that tracked from the Great Lakes as a related cold front traveled southeastward and became stationary over the Atlantic, extending from northern Florida to Bermuda. On July 5, the front spawned a separate cut-off cold-core low off the coast of the Carolinas. This complex scenario resulted in the formation of a tropical depression later during the day, which slowly meandered north-northeastward.[1][2] Tropical cyclones of this origin typically remain at a small size and evolve slowly, and Cindy complied to this pattern.[1]

Convection began to increase on July 6, supported on the basis that many showers were observed to the north of the depression. An anticyclone—a large mass of air rotating clockwise—intensified within the depression's vicinity, resulting in a tighter pressure gradient and increasing winds to the north of the center of the depression.[1] The depression intensified into Tropical Storm Cindy early on July 7,[2] and a reconnaissance flight into the storm late during the afternoon observed maximum sustained winds of 60–65 mph (95–100 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 997 mbar (hPa; 29.44 inHg).[1] Cindy began to curve westward late on July 7 as it reached peak intensity, with a minimum central pressure of 996 mbar (hPa; 29.41 inHg),[3] and drifted due west early on July 8 as a result of a maturing surface high to its north.[4] Steady intensification continued throughout the day, and the storm attained hurricane status during the morning of July 8.[2]

At approximately 2:45 UTC on July 9,[1] the hurricane made landfall near McClellanville, South Carolina.[5] Shortly thereafter, Cindy began re-curving northwestward along the Fall Line,[4] and eventually weakened to a tropical depression. The depression abruptly turned toward the east-northeast over North Carolina during the afternoon hours of July 9. Cindy then began to accelerate as it curved slightly towards the northeast, and eventually regained tropical storm status late on July 10 as it emerged into the Atlantic. Cindy scraped the southern fringe of the Delmarva Peninsula near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay at approximately 00:00 UTC on July 11, and rapidly traveled northeastward during the day. Cindy passed over Cape Cod near the mid-morning of July 11,[2] during which a series of shortwave troughs passed near the storm, producing high-level outflow that helped Cindy maintain intensity.[1] Later on July 11, Cindy moved ashore in New Brunswick and made landfall over Prince Edward Island the following day. The storm subsequently moved over Quebec and Labrador,[6] where it transitioned into an extratropical cyclone.[2]

Preparations and impact

Cindy prompted a hurricane watch and gale warnings for areas extending from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, to Charleston, South Carolina,[7] and a hurricane warning for areas between Beaufort and Georgetown, South Carolina, on July 8.[5] A preliminary alert was issued for naval and marine areas in the Carolinas from Norfolk, Virginia.[8] Special forecasts from the Weather Bureau office in Columbia, South Carolina were activated on the radio at 16:50 UTC on July 8.[9] Several thousand people evacuated in areas of South Carolina, including Folly Beach, Sullivan's Island, Isle of Palms, and Pawleys Island.[10][11] The issuance of an emergency flood forecast for Columbia, South Carolina occurred as a result of Cindy.[9]

The highest rainfall total measured was 9.79 inches (249 mm) in Winnsboro, South Carolina, although unofficial sources east of Columbia, South Carolina, measured rainfall totals of up to 15 inches (380 mm).[9][12] Tides ranged from 1 to 4 feet (0.30 to 1.22 m) above normal.[5][13] A total of eleven tornadoes were reported in association with Cindy.[14] Only one direct death was caused by Cindy,[15] in addition to five indirect deaths.[16] Little damage was attributed to the hurricane, other than downed tree limbs and broken windows.[17] Damage from Cindy was estimated at $75,000 (1959 USD).[1]

South Carolina

A driver was killed in Georgetown on U.S. Route 17 after colliding with a fallen tree.[15] Along the main street of Georgetown, the Sampit River topped its banks, resulting in flooding that impacted business in the area.[18] At Georgetown, tides were about 2.5 feet (0.76 m) above normal during Cindy,[11] while at McClellanville, the point of landfall, tides were approximately 4 feet (1.2 m) above normal.[5] At Folly Beach, Sullivan's Island, and Isle of Palms, only 600 people of the normal population of approximately 6,500 chose not to evacuate.[11] Strong winds that accompanied Cindy snapped tree limbs, shattered a few windows, damaged roofs, and knocked power out in Charleston,[17][19] but little other damage was wrought. Several points throughout the state measured at least 3 inches (76 mm) of rainfall, including Columbia, Charleston, Myrtle Beach, and Sumter.[17]

The Congaree River rose dramatically near Columbia during the hurricane, where rainfall totaled 5.82 inches (148 mm),[20] although some reliable unofficial sources state the figure to be 15 inches (380 mm).[9] Several thousand sought safety in Red Cross shelters in schools and armories,[8][21] though the Weather Bureau announced it was safe for evacuees in Charleston to return to their homes shortly after the storm came ashore.[11] Most of the rainfall produced by Cindy was beneficial to drought-stricken regions, albeit not enough to provide significant relief.[5][10]

Elsewhere

As Cindy moved inland, tornadoes touched down in North Carolina, Virginia, and Maryland along the outer bands of the storm.[22] A tornado was observed near Nags Head around 17:40 UTC on July 10, and a second was observed 25 minutes later. Both tornadoes caused minimal damage – the first damaged four buildings and the second uprooted trees and toppled power poles. In addition, two waterspouts were noted offshore North Carolina, of which one was near New Topsail Beach in the mid-morning of July 8 and another near Sneads Ferry. No damage was reported from the waterspouts.[23]

Prior to the storm's landfall in the Carolinas, tides at Wilmington, North Carolina, were 2 feet (0.61 m) above normal;[7] tides were near the same level at other areas of the southern fringes of North Carolina.[23] In New England, five indirect deaths resulted from traffic accidents on highways as a result of the slippery conditions on roads wrought by Cindy's rains. At Boston, 2.37 inches (60 mm) of rainfall was measured, while 2.85 inches (72 mm) fell at Bedford.[16] Between the cities of Atlantic City, New Jersey, and Eastport, Maine, tides were 1 foot (0.30 m) to 3 feet (0.91 m) above normal.[13] Rainfall in the Mid-Atlantic peaked at 8.43 inches (214 mm) at Belleplain State Forest in New Jersey, while rainfall in New England peaked at 3.85 inches (98 mm) at Lake Konomoc, Connecticut.[24][25] Rainfall was also recorded in Georgia, Delaware, Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine.[4]

Most impacts in Canada occurred after the hurricane transitioned into an extratropical cyclone. Cindy brought strong winds and downpours along the coast of Nova Scotia. Many small vessels sought safety, but the ship Lady Godiva sank near North West Arm; the two people on board were later rescued. No damage was reported on the island itself. In New Brunswick, up to 2 inches (50 mm) of rainfall was produced by Cindy, although no damage is known to have been reported.[6]

See also

- List of United States hurricanes

- List of New England hurricanes

- Other storms with the same name

Notes

Footnotes

- Dunn, Gordon E. (December 1959). "The Hurricane Season of 1959" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. Miami, Florida: American Meteorological Society. 87 (12): 444–445. Bibcode:1959MWRv...87..441D. doi:10.1175/1520-0493-87.12.441. ISSN 1520-0493.

- "Easy to Read HURDAT 2011". Hurricane Research Division. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. August 2011. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- Dunn, Gordon E. (July 7, 1959). "Tropical Storm Cindy Advisory Number 2" (GIF). Miami Weather Bureau. Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved November 2, 2011.

- Roth, David M; Hydrometeorological Prediction Center (October 3, 2008). "Hurricane Cindy rainfall page". Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved June 10, 2012.

- "Preliminary report on Hurricane Cindy" (GIF). United States Department of Commerce. Washington, D.C.: Weather Bureau. July 1959. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- "Environnement Canada - Conditions atmosphériques et météorologie - Détaillée des Rapports de Dégâts - 1959-Cindy" (in French). Environment Canada. Retrieved November 16, 2011.

- Staff writer (July 8, 1959). "Hurricane Cindy Aims at Carolina". The Miami News. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- Staff writer (July 9, 1959). "Cindy Nears Coast Of South Carolina". The Washington Observer. Charleston, South Carolina. Associated Press. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- Purvis, John C. (July 13, 1959). "Resume' of Activities During the Passage of Hurricane Cindy" (GIF). MIC, Weather Bureau Airways Station. Columbia, South Carolina: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 1. Retrieved November 2, 2011.

- Staff writer (July 9, 1959). "Subdued Hurricane Cindy Brings Needed Rain". Raleigh, North Carolina: The Robesonian. Associated Press. Retrieved November 2, 2011.

- Staff writer (July 9, 1959). "Dying 'Cindy' Offers Rainy Night in Area". The Free Lance–Star. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- Roth, David M; Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in the Southeastern United States". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- Staff writer (July 10, 1959). "Cindy Flicks New England On Way to Bay of Fundy". Boston, Massachusetts: Lewiston Evening Journal. Associated Press. Retrieved November 2, 2011.

- Smith, John S. (July 1965). "The Hurricane-Tornado" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 93 (7): 458. Bibcode:1965MWRv...93..453S. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1965)093<0453:THT>2.3.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0493.

- McHugh, Robert (July 9, 1959). "Weakened Storm Crawling North". Charleston, South Carolina: The Rock Hill Herald. Associated Press. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- Staff writer (July 12, 1959). "New England Hit By A Soggy Cindy". The Miami News. Boston, Massachusetts. United Press International. Retrieved November 2, 2011.

- Staff writer (July 9, 1959). "Cindy Loses Punch". Charleston, South Carolina: Sarasota Journal. United Press International. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- Staff writer (July 9, 1959). "Cindy Hisses At Carolinas — Heavy Rain". The Miami News. Charleston, South Carolina. Associated Press. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- Fraser p. 411

- Staff writer (July 10, 1959). "Cindy Dumps Rain On Coastal States". The Portsmouth Times. Associated Press. Retrieved November 2, 2011.

- Staff writer (July 9, 1959). "Storm Cindy Big Blowhard". Lakeland Ledger. Charleston, South Carolina. Associated Press. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- Staff writer (July 11, 1959). "Latest Cindy". The Washington Reporter. Boston, Massachusetts. United Press International. Retrieved November 2, 2011.

- Hardy, Albert V.; State Climatologist's Office, Weather Bureau Airways Station (July 15, 1959). Report on Tropical Storm Cindy (GIF) (Report). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 10, 2012.

- Roth, David M; Weather Prediction Center (2012). "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in the Mid-Atlantic United States". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- Roth, David M; Hydrometeorological Prediction Center (2012). "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall for the New England United States". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

Further reading

- Fraser, Walter J. (1991). Charleston! Charleston!: The History of a Southern City. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 0-87249-797-6.