1950 Assam–Tibet earthquake

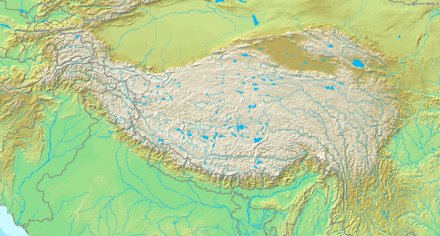

The 1950 Assam–Tibet earthquake,[4] also known as the Assam earthquake,[4] occurred on 15 August and had a moment magnitude of 8.6. The epicentre was located in the Mishmi Hills, known in Chinese as the Qilinggong Mountains (祁灵公山), south of the Kangri Garpo and just east of the Himalayas in the North-East Frontier Agency part of Assam, India. This area, south of the McMahon Line and now known as Arunachal Pradesh, is today disputed between China and India.

| |

| UTC time | 1950-08-15 14:09:34 |

|---|---|

| ISC event | 895681 |

| USGS-ANSS | ComCat |

| Local date | August 15, 1950 |

| Local time | 7:39 pm IST |

| Magnitude | 8.6 Mw [1] |

| Depth | 15 km (9.3 mi) [1] |

| Epicenter | 28.36°N 96.45°E [1] |

| Type | Strike-slip [2] |

| Areas affected | Tibet, Assam |

| Max. intensity | XI (Extreme) [3] |

| Casualties | 4,800 |

Occurring on a Tuesday evening at 7:39 pm Indian Standard Time, the earthquake was destructive in both Assam (India) and Tibet (China), and approximately 4,800 people were killed. The earthquake is notable as being the largest recorded quake caused by continental collision rather than subduction, and is also notable for the loud noises produced by the quake and reported throughout the region.

Geology

In an attempt to further uncover the seismic history of Northeast India, field studies were conducted by scientists with the National Geophysical Research Institute and Institute of Physics, Bhubaneswar. The study discovered signs of soil liquefaction including sills and sand volcanoes inside of at least twelve trenches in alluvial fans and on the Burhi Dihing River Valley that were formed by past seismic activity. Radiocarbon dating identified the deposits at roughly 500 years old, which would correspond with a recorded earthquake in 1548.[5]

Earthquake

The earthquake occurred in the rugged mountainous areas between the Himalayas and the Hengduan Mountains. The earthquake was located just south of the McMahon Line between India and Tibet, and had devastating effects in both regions. Today this area is claimed as part of Zayü and Mêdog Counties in the Tibet Autonomous Region by China, and as part of Lohit District in Arunachal Pradesh by India. This great earthquake has a calculated magnitude of 8.6 and is regarded as one of the most important since the introduction of seismological observing stations.

It was the sixth largest earthquake of the 20th century.[6] It is also the largest known earthquake to have not been caused by an oceanic subduction. Instead, this quake was caused by two continental plates colliding.

Aftershocks were numerous; many of them were of magnitude 6 and over and well enough recorded at distant stations for reasonably good epicentre location. From such data, the Indian Seismological Service, established an enormous geographical spread of this activity, from about 90 deg to 97 deg east longitude, with the epicentre of the great earthquake near the eastern margin.

Impact

The 1950 Assam–Tibet earthquake had devastating effects on both Assam and Tibet. In Assam, 1,526 fatalities were recorded[7] and another 3,300 were reported in Tibet[8] for a total of approximately 4,800 deaths.

Alterations of relief were brought about by many rock falls in the Mishmi Hills and surrounding forested regions. In the Abor Hills, 70 villages were destroyed with 156 casualties due to landslides. Landslides blocked the tributaries of the Brahmaputra. In the Dibang Valley, a landslide lake burst without causing damage, but another at Subansiri River opened after an interval of 8 days and the wave, 7 m (23 ft) high, submerged several villages and killed 532 people.

The shock was more damaging in Assam, in terms of property loss, than the earthquake of 1897. In addition to the extreme shaking, there were floods when the rivers rose high after the earthquake bringing down sand, mud, trees, and all kinds of debris. Pilots flying over the meizoseismal area reported great changes in topography. This was largely due to enormous landslides, some of which were photographed.

In Tibet, Heinrich Harrer reported strong shaking in Lhasa and loud cracking noises from the earth.[9] Aftershocks were felt in Lhasa for days. In Rima, Tibet (modern-day Zayü Town), Frank Kingdon-Ward, noted violent shaking, extensive slides, and the rise of the streams. Helen Myers Morse, an American missionary living in Putao, northern Burma at the time, wrote letters home describing the main shake, the numerous aftershocks, and of the noise coming out of the earth.[10]

One of the more westerly aftershocks, a few days later, was felt more extensively in Assam than the main shock. This led certain journalists to the belief that the later shock was 'bigger' and must be the greatest earthquake of all time. This is a typical example of the confusion between the essential concepts of magnitude and intensity. The extraordinary sounds heard by Kingdon-Ward and many others at the times of the main earthquake have been specially investigated. Seiches were observed as far away as Norway and England. (p. 63–64.)

Future threat

An article in Science, published in response to the 2001 Bhuj earthquake, calculated that 70 percent of the Himalayas could experience an extremely powerful earthquake. The prediction came from research of the historical records from the area as well as the presumption that since the 1950 Medog earthquake enough slippage has taken place for a large earthquake to occur.[11] In 2015, the Himalayas were hit by a 7.8-magnitude earthquake with an epicenter further west in Nepal.

See also

References

- ISC (2015), ISC-GEM Global Instrumental Earthquake Catalogue (1900–2009), Version 2.0, International Seismological Centre

- USGS. "M8.6 - eastern Xizang-India border region". United States Geological Survey.

- USGS (September 4, 2009), PAGER-CAT Earthquake Catalog, Version 2008_06.1, United States Geological Survey

- "Historic Earthquakes, Assam - Tibet". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on November 10, 2016. Retrieved January 24, 2012.

- Reddy, D.V.; Nagabhushanam, P.; et al. (September 2009). "The great 1950 Assam Earthquake revisited: Field evidences of liquefaction and search for paleoseismic events". Tectonophysics. 474 (3): 463–472. Bibcode:2009Tectp.474..463R. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2009.04.024.

- "Largest Earthquakes in the World Since 1900". United States Geological Survey. September 20, 2011. Archived from the original on 7 November 2010. Retrieved December 17, 2010.

- "Significant Earthquake INDIA-CHINA". National Geophysical Data Center. August 15, 1950. Retrieved November 24, 2016.

- "8·15墨脱地震". Baidu. Baidu. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- Harrer, Heinrich (1953). Seven Years in Tibet. Putnam.

- Myers Morse, Helen (2003). Once I Was Young. Terre Haute, Indiana. pp. 167–171.

- "Quake in Himalayas: US & Indian experts differ". The Statesman. September 6, 2001.

External links

- At Khowang – A photo by Dhaniram Bora

- The International Seismological Centre has a bibliography and/or authoritative data for this event.