Mêdog County

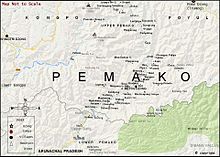

Mêdog, Metok, or Motuo County (Tibetan: མེ་ཏོག་རྫོང་,, Wylie: Metog Rdzong ; simplified Chinese: 墨脱县; traditional Chinese: 墨脫縣; pinyin: Mòtuō Xiàn), also known as the Pemako (Tibetan: པདྨ་བཀོད་, Wylie: pad ma bkod, THL: Pémakö, ZYPY: Bämagö "Lotus Array", Chinese: 白马岗), is a county as well as a traditional region of the prefecture-level city of Nyingchi in the Tibet Autonomous Region of the People's Republic of China (PRC).

Mêdog County 墨脱县 • མེ་ཏོག་རྫོང་། | |

|---|---|

County | |

.png) Location of Mêdog County (yellow) within Nyingchi City (yellow) and the Tibet Autonomous Region | |

Mêdog Location of the seat in Tibet Autonomous Region | |

| Coordinates (Mêdog government): 29°19′30″N 95°19′59″E | |

| Country | People's Republic of China |

| Autonomous Region | Tibet |

| Prefecture-level city | Nyingchi |

| County seat | Metog |

| Area | |

| • Total | 7,000 km2 (3,000 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 2,500 m (8,200 ft) |

| Population (2010 Census) | |

| • Total | 10,963[1] |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (China Standard) |

Geography

Medog County is located in the southeast of the Tibet Autonomous Region and at the lower branch of Yarlung Tsangpo River. Medog County covers an area of 30,553 km2 (11,797 sq mi).

The average altitude of the county is 1,200 m (3,900 ft) above sea level. The county is located in the average altitude ranging from 1,000–3,500 metres (3,300–11,500 ft) above seas level. It stretches from south of Kongpo and Bomê County through the lower Yarlung Tsangpo River upto Arunachal Pradesh, surrounded by high mountains: the tallest is Namcha Barwa at 7,782 metres (25,531 ft)). Pemako has lush vegetation and many species of wild animals. Unlike other parts of Tibet, it receives plenty of rain, and has diverse biomes: there are subalpine coniferous forests in the north and temperate coniferous forest in the south in the low-lying area of the Yarlung Tsangpo gorges.

The Yarlung Tsangpo flows through 1,500 km (930 mi) eastward when it reaches Mount Namcha Barwa, its bend making a U shape turn to penetrate into lower Himalayan ranges, thus carving out the Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon, one of the deepest canyons in the world. Water dropping above 3,000 meters near Pei, about 300 metres from the end of the gorge.

Climate and wildlife

Medog has a favourable climate caused by the relatively low elevations in parts of the county (down to just 600 m above sea level in the Yarlung Zangbo river valley) and by the South Asian monsoon, which brings moisture from the Indian Ocean. The area is lush and covered with trees and includes the Medog National Animal and Plant Reserve Area. It has more than 3,000 species of plants, 42 species of rare animals under special state protection, and over a thousand hexapod species.

History

The majority of the people in Pemako speak the Tshangla language. Historically, Tshangla speakers migrated from eastern Bhutan around the 17th century during the Drukpa conquest led by Zhabdrung Ngawang Ngamgyal. It was reported that over several hundred families made their way to Pemako. Among the first settlers were the Ngatshang and Chitsang clans, later joined by many more people who left their homeland in a quest for better life.

When the first Tsangla people arrived in Pemako they settled in the lower Yarlung valley, surrounded by Kongpopas in the northwest, Pobas in the northeast, and Lhopas in the south. The Tsangla adopted many customs from their neighbors but still retained their original language. Historically, the area came under the rule of Powo (Bomê) kings who ruled the entirety of Pemako (now Medog). During Powo rule, Pemako residents had good relations with the Tibetans. They jointly fought against the Tani (Adis) and Mishmis who regularly disturbed the pilgrimage.

By 1931 the Tibetan government (Ganden Phodrang) was able to dismantle the Powo kingdom and the region came under the direct rule of the central Tibetan Government in Lhasa. Ganden Phodrang had its governor stationed in Medog Dzong, who looked after the territory and established communications between Lhasa and Pemako. Compulsory taxes in cash or goods were to be paid to Lhasa. The region of Pemako was divided among different monasteries and different aristocratic families. Some regions of Pemako pay tax to the Sera Monastery in the form of grains, chillis, bamboo poles for prayer flags (Dharchen), products made of cane, medicinal herbs such as yertsa-goonbu, mushroom, and animal skin. Some regions of Pemako were under Kyabje Dudjom Rinpoche as a monastic entitlement of the Nyingma lineage.

Transportation

Mêdog was the last county without permanent road access in Tibet, due to the landscape of several high-elevation mountain ranges. A first, simple road was built in the 1970s, yet it was usually blocked by ice and snow on the mountains in the winter, making it only accessible seasonally. In December 2010, the Chinese government announced a project to renovate the road into a permanent highway from Bomê to Mêdog County,[2] including excavation of a new tunnel under the mountain range. The renovation was completed in 2013.

Before the completion of the highway, transportation in Mêdog primarily relied on foot. Hiking to Mêdog is also a popular activity among tourists, although it is generally considered highly exhausting and risky. A primary route for accessing Mêdog begins in Bomê County, which inspired the route of the current permanent highway. Another important route for traveling to Mêdog on foot starts in Pai (派镇, a township in Mainling County) and travels all the way along the Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon to Mêdog township, which is a route particularly popular among backpackers.

Economy

Farming is the main industry in Medog County. It is abundant with rice, soybean, cotton and gingelly. Hairy deerhorn, gastrodia tubers, musk, and hedgehog hydnum are also special products of the area.

Demography

Medog county has a population of 10,963 according to 2010 census,[1] and most people who live in the county are of Tshangla, Khamba people and Lhoba ethnic group. The most renowned part of Medog is known as Pemako. Its inhabitants speak a form of Tshangla (Chinese: 仓洛; pinyin: Cāngluò) related to that spoken in eastern Bhutan. They practice the Nyingma tradition of Tibetan Buddhism.

Population according to 2009 in Various villages:

- Medog/Metog Town (墨脱镇) with a total population of 1,878

- Baibung/Bepung Township (背崩乡) with a total population of 2,138

- Dexing/Deshing Township (德兴乡) with a total population of 1,549

- Damu/Tamu Township (达木乡) with a total population of 729

- Phomshen Township (旁辛乡) with a total population of 1,266

- Gyalhasa Township (加热萨乡) with a total population of 812

- Gandain Township (甘登乡) with a total population of 647

- Gedang Township (格当乡) with a total population of 680[3]

Medog county is diverse, with different ethnicities intermixing for many centuries. Residents include Tshangla people, Kongpopas, Poba, and Khampa Tibetans, and Lhoba people (Adi, Mishmis) live here, while Tshangla speakers make up the majority about 60% of the total population of 10,000–12,000 (According to 2001 census in Metok county (Dzong) there were about 10,000 people). People in Pemako called themselves Pemakopa. They also call themselves Monba as they originally migrated to the region of Mon which comprises present Bhutan and Tawang. In exile Pemakopa people spread through the world, but mainly concentrated in Tibetan settlements of Miao choephelling, Tezu Dhargyeling, Tuting and area, Orissa-Jerang camp, Tibetan Women Centre – Rajpur, Clementown[4], Delhi area.[5] There are approximately 100 individuals in Europe, 130 in the United States and 980 in Canada.

Frank Kingdon-Ward was the first Westerner to describe the area in his 1925 book, Riddle of the Tsangpo Gorges. In his 1994 Tibet Handbook, Hong Kong-born Victor Chan describes the extremely difficult trek from Pemakö Chung to the beyul Gonpo Ne, one of the remotest spots on earth. A modern journey by Ian Baker and his National Geographic-sponsored team to Pemakö received book-length treatment in his 1994 The Heart of the World.

Since 1904 the year Kabgye Dudjom Rinpoche was born in Pemako, people from all over Tibet, especially from Khams, Golok and Utsang, entered Pemako and settled near their lama.

Ever since Pemako was first opened to outside world thousands of people settled in the region. Among them, earliest were the Tshangla people from Eastern Bhutan who fled their homeland and took refuge there. Among the first clans of Tshangla people were the Ngatsangpas (Snga Tsang pa) who paved ways for others to join them in their plight for a promised land free from sufferings. The exodus of Tshangla community continued from beginning of the 18th century right until the early 20th century. Political and religious turmoil in Tibet forced many Tibetans to join Tshangla people in Pemako a land where religious serenity pledge through many revered Lamas who had been to this land, prophesied by Padmasambhava in the mid-8th century to be a land of final call where devotees would be flocking at the time of religious persecutions, the last sanctuary for Buddhism, with the time Pemako's popularity grew more and more, with the popularity many Tibetan people particularly from Kham followed their Lamas and settled alongside Tshangla populace. Over the period of time Tibetans and Tshangla migrants amalgamated to form an homogeneous group called Pemakopas (Pad-ma dkod pa). The process of infusion gave birth to a new Tshangla dialect called Pemako dialect.

Language

The Pemako Tshangla dialect (Tibetan: པདྨ་བཀོད་ཚངས་ལ་སྐད་, Wylie: Padma-kod Tsangla skad, also Padma kod skad) is the predominant language in the Pemako region of Tibet and an adjoining contiguous area south of the McMahon line in Arunachal Pradesh in India. Though Tshangla is not a Tibetan language, it shares many similarities with Classical Tibetan, particularly in its vocabulary. Many Tibetan loanwords are used in Pemako, due to centuries of close contact with various Tibetan tribes in the Pemako area. The Pemako dialect has undergone tremendous changes due to its isolation and Tibetan influence. Unique Tsanglha dialect of is in danger of extinction due to demographic changes and migration in Tsanglha speaking regions in Tibet Autonomous Region, Eastern Bhutan, and Arunachal Pradesh. Dominant cultures that are coming in contact with Tsanglha is altering and influence the ability of this dialect to survive.

Tsangla or Pemakopa is one of the many languages of Tibet. Tsangla is widely spoken and understood by many non-Tsangla speakers in the area. People of Pemako also speak Standard Tibetan. The Pemakopa people also speak other dialects of Tibet, such as Khampa, Kongpo and Zayul dialects. Today inside Tibet Pemakopa people are also well versed in Mandarin Chinese. As the majority are Pemakopas, spoken Tsangla is well established. Pemakopa dialect of Tsangla doesn't have tones, unlike Standard Tibetan, but Tsangla language in Pemako uses high and low accents, which are absent in other Tsangla dialects. Pemakopa dialect's numerical denominations up to 20 and higher are counted in Standard Tibetan. Globally Tsangla language has about 140,000–160,000 speakers.

Religion

Majority of people in Pemako follow Nyingma tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. Some follow the indigenous Bon tradition as well. Lhoba people in Pemako practice a combination of animism and Buddhism.

Pemako Chung

Pemako Chung (pad ma bkod chung) is a partially deserted monastery destroyed in the 1950 Medog earthquake. There are around three lamas in the monastery recently.

Notes

- "Mòtuō Xiàn (County, China) - Population Statistics, Charts, Map and Location". www.citypopulation.de. Archived from the original on 2015-02-03. Retrieved 2015-02-06.

- Edward Wong (December 16, 2010). "Isolated County in Tibet Is Linked to Highway System". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 25, 2013. Retrieved December 17, 2010.

- "Administrative Division of Medog". Archived from the original on 2015-02-09. Retrieved 2015-02-06.

- [thetibetpost.com/en/features/education-and-society/4838-dehradun-another-home-away-from-home-for-exiled-tibetans-in-india "Dehradun – Another Home away from Home for exiled Tibetans in India"] Check

|url=value (help). 24 December 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2020. - "Between worlds: 60 years of the Tibetan community in India". 16 June 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2020.