Hirosaki Castle

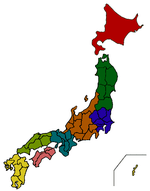

Hirosaki Castle (弘前城, Hirosaki-jō) is a hirayama-style Japanese castle constructed in 1611. It was the seat of the Tsugaru clan, a 47,000 koku tozama daimyō clan who ruled over Hirosaki Domain, Mutsu Province, in what is now central Hirosaki, Aomori Prefecture, Japan. It was also referred to as Takaoka Castle (鷹岡城 or 高岡城, Takaoka-jō).

| Hirosaki Castle | |

|---|---|

弘前城 | |

| Hirosaki, Aomori, Japan | |

Hirosaki Castle | |

Aerial photograph | |

| Coordinates | |

| Type | hirayama-style Japanese castle |

| Height | three stories |

| Site information | |

| Condition | National Important Cultural Property |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1611, reconstructed in 1810 |

| Built by | Tsugaru clan |

| In use | 1611-1871 |

| Materials | Wood, stone |

Background

Hirosaki Castle measures 612 meters east-west and 947 meters north-south. Its grounds are divided into six concentric baileys, which were formerly walled and separated by moats. It is unusual in that its Edo period tenshu and most of its outline remains intact. Noted historian and author Shiba Ryōtarō praised it as one of the "Seven Famous Castles of Japan" in his travel essay series Kaidō wo Yuku.

History

During the late Sengoku period, former Nambu retainer Ōura Tamenobu was awarded revenues of 45,000 koku by Toyotomi Hideyoshi for his role in the Battle of Odawara in 1590. He took the family name of Tsugaru at that time. At the Battle of Sekigahara, he sided with Tokugawa Ieyasu and was subsequently confirmed as lord of Hirosaki Domain with revenues increased to 47,000 koku.

In 1603, he began work on a castle in Hirosaki; however, work was suspended with his death in Kyoto in 1604. Work was resumed by his successor, Tsugaru Nobuhira in 1609, who stripped Horikoshi Castle and Ōura Castle of buildings and materials in order to speed its completion.

The current castle was completed in 1611. However, in 1627, the 5-story tenshu was struck by lightning and destroyed by fire. It was not rebuilt until 1810 when the present 3-story structure was erected, but at the southeast corner, rather than the original southwest location.[1] It was built by the 9th daimyō, Tsugaru Yasuchika.

With the Meiji Restoration and subsequent abolition of the han system, the Tsugaru clan surrendered the castle to the new Meiji government. In 1871, the castle was garrisoned by a detachment of the Imperial Japanese Army, and in 1873 the palace structures, martial arts school and most of the castle walls were pulled down. In 1894, the castle properties were donated by the Tsugaru clan to the government for use as a park, which opened to the general public the following year. In 1898, an armory was established in the former Third Bailey by the IJA 8th Division. In 1906, two of the remaining yagura burned down. In 1909, a four-meter-tall bronze statue of Tsugaru Tamenobu was erected on the site of the tenshu. In 1937, eight structures of the castle received protection from the government as “national treasures”. However, in 1944, during the height of World War II, all of the bronze in the castle, including roof tiles and decorations, were stripped away for use in the war effort.

In 1950, under the new cultural properties protection system, all surviving structures in the castle (with the exception of the East Gate of the Third Bailey) were named National Important Cultural Properties (ICP). In 1952, the grounds received further protection with their nomination as a National Historic Site.[2] In 1953, after reconstruction, the East Gate of the Third Bailey also gained ICP status, giving a total of nine structures within the castle with such protection.

Extensive archaeological excavations from 1999-2000 revealed the foundations of the former palace structures and a Shinto shrine. In 2006, Hirosaki Castle was listed as one of the 100 Fine Castles of Japan by the Japan Castle Foundation.

In order to repair the castle's stone walls directly below the tenshu, the entire tenshu was removed in autumn 2015, and will be returned to its original position in 2021.[3].

Structures and gardens

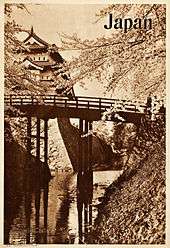

The current tenshu of the castle was completed in 1811. It is a three-story building with three roofs, and a height of 14.4 meters. The design is smaller than early Edo-period varieties of tenshu, and it was built on a corner of the inner bailey on the site of a yagura, rather than the stone base of the original tenshu. The small size was partly due to the restricted finances of the domain towards the end of the Edo period, but its location and design were also intended to alleviate concerns which might be raised by the Tokugawa shogunate should a larger structure be built. At present, it is a separate standing structure; however, prior to 1896 it had an attached gatehouse.

The tenshu is surrounded by three surviving yagura from the Edo period (the Ninomaru Tatsumi Yagura, Ninomaru Hitsujisaru Yagura, Ninomaru Ushitora Yagura), on its second bailey, and five surviving gates (Sannomaru Ōtemon Gate, Sannomaru East Gate, Ninomaru South Gate, Ninomaru East Gate, Kitanokuruwa North Gate) in the walls of its second and third baileys. All of these structures, including the tenshu itself, are National Important Cultural Properties.

The surrounding Hirosaki Park around the castle grounds is one of Japan's most famous cherry blossom spots. Over a million people enjoy the park's 2600 trees (which were originally planted around in grounds in 1903) during the sakura matsuri (cherry blossom festival) when the cherry blossoms are in bloom, usually during the Japanese Golden Week holidays in the end of April and beginning of May.

Important Cultural Properties

Festival

Hirosaki city holds an annual winter four-day Hirosaki Castle Snow Lantern Festival. The festival had attracted 310,000 visitors in 1999 and included 165 standing snow lanterns and 300 mini snow caves.[13]

References

- Hinago, Motoo (1986). Japanese Castles. Kodansha International Ltd. and Shibundo. p. 134. ISBN 0870117661.

- Agency for Cultural Affairs (in Japanese)

- 弘前城石垣修理事業とは - Hirosaki Castle official website(02/13/2020)

- "弘前城 三の丸追手門" [Sannomaru Ōtemon Gate] (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "弘前城三の丸東門" [Sannomaru Higashi Gate] (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "弘前城 北の郭北門(亀甲門)" [Kitanokuruwa North Gate] (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "弘前城 二の丸南門" [Ninomaru South Gate] (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "弘前城 二の丸東門" [Ninomaru East Gate] (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "弘前城 二の丸未申櫓" [Ninomaru Hitsujisaru Yagura] (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "弘前城 二の丸辰巳櫓" [Ninomaru Tatsumi Yagura] (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "弘前城 二の丸丑寅櫓" [Ninomaru Tatsumi Yagura] (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "弘前城 天守" [Hirosaki-ji Tenshu] (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- Anthony Rausch (1 June 2001). A Year With the Local Newspaper: Understanding the Times in Aomori Japan, 1999. University Press of America. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-0-7618-2050-5. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

Bibliography

- Benesch, Oleg and Ran Zwigenberg (2019). Japan's Castles: Citadels of Modernity in War and Peace. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 374. ISBN 9781108481946.

- Schmorleitz, Morton S. (1974). Castles in Japan. Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Co. pp. 144–145. ISBN 0-8048-1102-4.

- Motoo, Hinago (1986). Japanese Castles. Tokyo: Kodansha. p. 200 pages. ISBN 0-87011-766-1.

- Mitchelhill, Jennifer (2004). Castles of the Samurai: Power and Beauty. Tokyo: Kodansha. p. 112 pages. ISBN 4-7700-2954-3.

- Turnbull, Stephen (2003). Japanese Castles 1540-1640. Osprey Publishing. p. 64 pages. ISBN 1-84176-429-9.

External links

![]()

.jpg)