Ōzu Castle

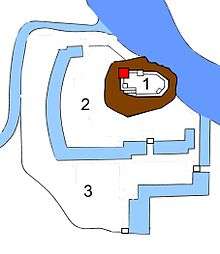

Ōzu Castle (大洲城, Ōzu-jō), also known as Jizōgatake Castle (地蔵ヶ嶽城, Jizō-ga-take-jō), is a castle located in Ōzu, Ehime Prefecture, Japan. Early defensive structures date back to early 14th century by Utsunomiya Toyofusa. In 1888 deterioration of the castle keep (天守, tenshu) led to its demolition, but it was accurately re-constructed in 2004.

History

Local records[1] state that, by 1331, barricades and small fortresses punctuated the Jizōgatake, an strategic mound overhanging the Hiji River (肱川, Hiji-kawa) . The defensive compound as it stands today, however, was not erected until 1585–1617. Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu unification campaigns brought constant shifts on the incumbents of Ōzu domain (大洲藩, Ōzu-han), including Wakisaka Yasuharu, Kobayakawa Takakage, Tōdō Takatora, and Toda Katsutaka warlords. Among them, renown castle designer Takatora is believed to have been the major contributor to the overall outline of the current structure.

In 1617, alighting from Yonago province, Katō Sadayasu took possession of the Ōzu domain. The Katō clan retained control of the domain during 13 generations, until the onset of the Meiji Restoration (1868).

During the Meiji era (1868-1912), abandoned and exposed to the mercy of inclement weather and natural hazards, the castle deteriorated rapidly. Threatening collapse, in 1888 it was decided to demolish the keep. Nonetheless, its two surrounding turrets (櫓, yagura), Koran Yagura and Daidokoro Yagura, were left intact. These two elements, built in late Edo period (1603-1868), as well as the Owata and the Minami Sumi turrets were declared in 1957 Important Cultural Property by the Agency for Cultural Affairs of the Japanese Government. [2]

Recent developments

In 2004, local citizens' & city officials' efforts culminated in the completion of a new keep at a cost of 1.6 billion JPY.

Old photographs, old maps and the discovery of an old model -depicting its original structure- permitted a faithful reconstruction. Only traditional assembling techniques and natural materials were employed. Historic accuracy was privileged to comfort and ease of construction. The project brought new life to ebbing carpenter and blacksmith craftsmanship.

At 19.15 m high, it stood as the tallest timber structure to have been erected since the enactment of the first post-war building regulations in 1950, Building Standards Law (建築基準法, kenchiku kijun hō) .

The castle is open to visitors. In a bid to revive the local economy through tourism overnight stays are also possible.[3]

Images

Ōzu Castle & Hiji River at dusk

Ōzu Castle & Hiji River at dusk Ōzu Castle and Hiji River

Ōzu Castle and Hiji River Cherry blossom at Ōzu Castle

Cherry blossom at Ōzu Castle

See also

References

- 大洲市詩 増補改訂(上、下) 1996年 (JP only) Municipal History Records. Ōzu City. 1996 (vol. I & II)

- Turnbull, Steven (2003). Japanese Castles 1540-1640 (Fortress). Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-429-0.

- https://edition.cnn.com/travel/article/ozu-castle-town-urban-regeneration/index.html

- Benesch, Oleg and Ran Zwigenberg (2019). Japan's Castles: Citadels of Modernity in War and Peace. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 374. ISBN 9781108481946.

- Motoo, Hinago (1986). Japanese Castles. Tokyo: Kodansha. pp. 200 pages. ISBN 0-87011-766-1.

External links

![]()