Odawara Castle

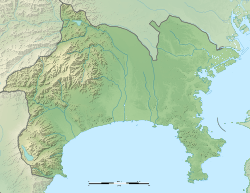

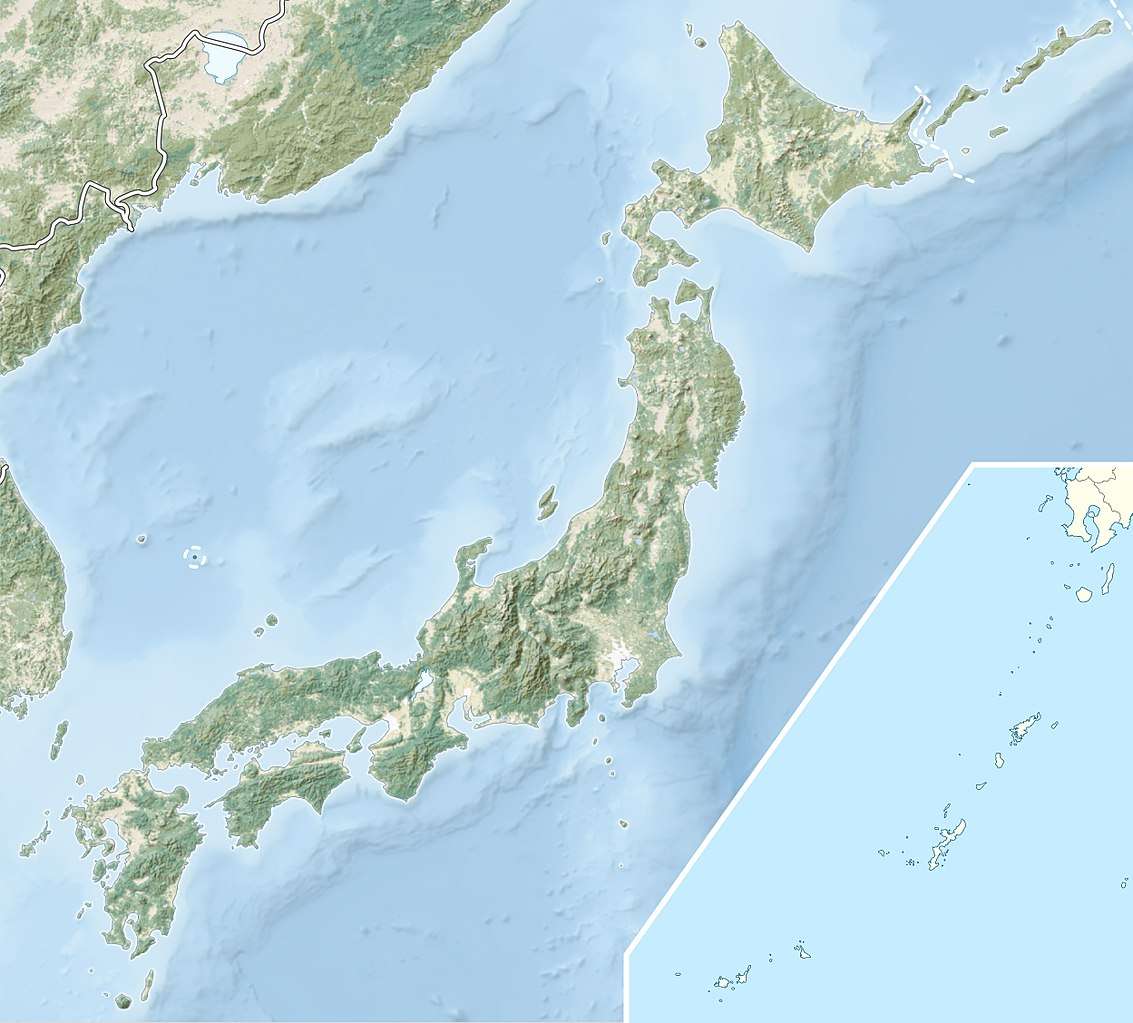

Odawara Castle (小田原城, Odawara-jō) is a landmark in the city of Odawara in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan.

| Odawara Castle 小田原城 | |

|---|---|

| Odawara, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan | |

Odawara Castle | |

Odawara Castle 小田原城  Odawara Castle 小田原城 | |

| Coordinates | |

| Type | Hirayama-style Japanese castle |

| Site information | |

| Open to the public | yes |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1447, rebuilt 1633, 1706 |

| In use | Kamakura period-1889 |

| Battles/wars | Siege of Odawara (1561) Siege of Odawara (1569) Siege of Odawara (1590) |

History

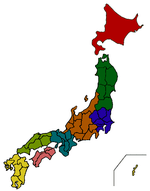

Odawara was a stronghold of the Doi clan during the Kamakura period, and a fortified residence built by their collateral branch, the Kobayakawa clan, stood on the approximate site of the present castle. After the Uesugi Zenshū Revolt of 1416, Odawara came under the control of the Omori clan of Suruga. They were in turn defeated by Ise Moritoki of Izu,[1] founder of the Odawara Hōjō clan in 1495. Five generations of the Odawara Hōjō clan improved and expanded on the fortifications of Odawara Castle as the center of their domains, which encompassed most of the Kantō region.

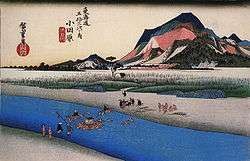

During the Sengoku period, Odawara Castle had very strong defenses, as it was situated on a hill, surrounded by moats with water on the low side, and dry ditches on the hill side, with banks, walls and cliffs located all around the castle, enabling the defenders to repel attacks by Uesugi Kenshin in 1561 and Takeda Shingen in 1569. In 1587, the defences of the castle were greatly expanded by the Odawara Hōjō in anticipation of the coming conflict with Toyotomi Hideyoshi. However, during the Battle of Odawara in 1590, Hideyoshi forced the surrender of the Odawara Hōjō without storming the castle through a combination of a three-month siege and bluff. After ordering most of the fortifications destroyed, he awarded the holdings of the Odawara Hōjō to his leading general Tokugawa Ieyasu.

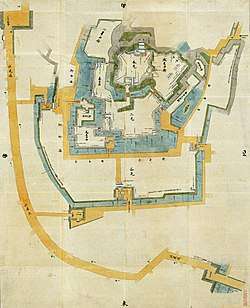

Edo period Odawara Castle

After Ieyasu completed Edo Castle, he turned site of Odawara Castle over to one of his senior retainers, Ōkubo Tadayo, who reconstructed the castle in its present form on a considerably reduced scale, with the entire castle fitting inside what was once the third bailey of the Sengoku period Hōjō castle. However, his successor Ōkubo Takachika was dispossessed by the shogunate in 1614. From 1619-1623, the castle was assigned to Abe Masatsugu. After 1623, Odawara Domain reverted to tenryō status and a palace was constructed in the inner bailey to serve as a retirement home of Shōgun Tokugawa Hidetada; however, Hidetada chose to remain in Edo during this retirement. On his death, Odawara Domain was revived as an 85,000 koku holding for Inaba Masakatsu, the eldest son of Kasuga no Tsubone, the wet nurse to Shōgun Tokugawa Iemitsu. Iemitsu visited Odawara Castle in 1634. Under the Inaba clan, the castle was extensively renovated. In 1686, the Inaba were transferred, and the Ōkubo clan returned to Odawara, with the domain expanded in kokudaka to 103,000 koku. The castle suffered great damage during the 1703 Genroku earthquake, which destroyed most of the castle structures. The donjon was restored by 1706, but the rest of the castle took until 1721. Extensive damage occurred again during the 1782 Tenmei earthquake and once more during the 1853 Kaei earthquake. During the Boshin War of the Meiji restoration, Ōkubo Tadanori permitted the pro-Imperial forces of the Satchō Alliance to pass through Odawara on their way to Edo without opposition.[2]

Odawara Castle in the modern era

The new Meiji government ordered the destruction of all former feudal fortifications, and in compliance with this directive, all structures of Odawara Castle were pulled down from 1870–1872. In 1893, the stone base of the former donjon become the foundation for a Shinto shrine, the Ōkubo Jinja, dedicated to the spirits of the generations of Ōkubo daimyō. In 1901, the Odawara Imperial Villa was constructed within the site of the former inner and second bailies. The Imperial Villa was destroyed by the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake, which also caused many of the stone facing on the castle ramparts to collapse. Repair work was made to the stone walls from 1930–1931, but with very poor workmanship. In 1934, two of the remaining yagura (which had been destroyed in the 1923 earthquake) were restored, but on a half-scale.

In 1938, the castle site was proclaimed a National Historic Site,[3] with the area under historic preservation restrictions expanded in 1959, and again in 1976 based on further archaeological investigations.

In 1950, repairs were made to the stone base of the former donjon, which had been in ruins since the Great Kantō earthquake, and the area was made into the Odawara Castle Park, which included an art museum, local history museum, city library, amusement park and zoo. The three-tiered, five-storied donjon, the top floor of which is an observatory, was rebuilt in 1960 out of reinforced concrete to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the proclamation of Odawara as a city. However, the reconstructed donjon is not historically accurate, as the observation deck was added at the insistence of the Odawara City tourism authorities. Plans have been discussed since the late 1960s on a more accurate restoration of the central castle grounds to its late Edo period format. These plans resulted in the reconstruction of the Tokiwagi Gate (常磐木門) in 1971, the Akagane Gate (銅門) in 1997, and the Umadashi Gate (馬出門) in 2009. The castle tower was remodelled from July 2015 until April 2016 to improve earthquake resistance and to modernise its exhibits. Odawara City government donated all entry fees on the day of the re-opening to Kumamoto City government, to be put towards repairs to Kumamoto Castle that was damaged in the 2016 Kumamoto earthquakes.[4]

The reconstructed Odawara Castle was listed as one of the 100 Fine Castles of Japan by the Japan Castle Foundation in 2006.

The remains of Later Hōjō clan era`s Odawara Castle

Hachimanyama kokaku Higashi Compound

Hachimanyama kokaku Higashi Compound Dry moat between Honmaru and Ninomiya-jinja Shrine

Dry moat between Honmaru and Ninomiya-jinja Shrine.jpg) Earthen wall of Honkuruwa(Shiroyama)

Earthen wall of Honkuruwa(Shiroyama) Earthen wall of Komine

Earthen wall of Komine Higashi moat of Komine1

Higashi moat of Komine1 Higashi moat of Komine2

Higashi moat of Komine2 Higashi moat of Komine3

Higashi moat of Komine3 Earthen wall and small compound between Higashi moat and Nakabori moat of Komine

Earthen wall and small compound between Higashi moat and Nakabori moat of Komine.jpg) Nakabori moat of Komine

Nakabori moat of Komine Kōrinjiyama Nishi moat

Kōrinjiyama Nishi moat Eathen wall of Sannomaru gaikaku Compound

Eathen wall of Sannomaru gaikaku Compound Sannomaru gaikaku Compound

Sannomaru gaikaku Compound Earthen wall of Sōgamae (Renjōin part)

Earthen wall of Sōgamae (Renjōin part)

Literature

- Benesch, Oleg and Ran Zwigenberg (2019). Japan's Castles: Citadels of Modernity in War and Peace. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 374. ISBN 9781108481946.

- Schmorleitz, Morton S. (1974). Castles in Japan. Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Co. pp. 144–145. ISBN 0-8048-1102-4.

- Motoo, Hinago (1986). Japanese Castles. Tokyo: Kodansha. p. 200 pages. ISBN 0-87011-766-1.

- Mitchelhill, Jennifer (2004). Castles of the Samurai: Power and Beauty. Tokyo: Kodansha. p. 112 pages. ISBN 4-7700-2954-3.

- Turnbull, Stephen (2003). Japanese Castles 1540-1640. Osprey Publishing. p. 64 pages. ISBN 1-84176-429-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Odawara Castle. |

Notes

- Sansom, George (1961). A History of Japan, 1334-1615. Stanford University Press. pp. 244–245. ISBN 0804705259.

- "小田原城の歴史【小田原城街歩きガイド】". www.scn-net.ne.jp. Retrieved 2019-12-31.

- Agency for Cultural Affairs (in Japanese)

- Hibino, Yoko Castles in Japan raise funds for quake-hit rival in Kumamoto May 2, 2016 Asahi Shimbun Retrieved June 29, 2016