Yorke Island (Queensland)

Yorke Island, or Masig in the Kalau Lagau Ya language, is a coral cay island of the Torres Strait Islands archipelago, situated in the eastern area of the central island group in the Torres Strait, at the top end of the Great Barrier Reef and northeast of the tip of Cape York Peninsula in Queensland, Australia.

| Native name: Masig | |

|---|---|

.png) Satellite image of Yorke Island | |

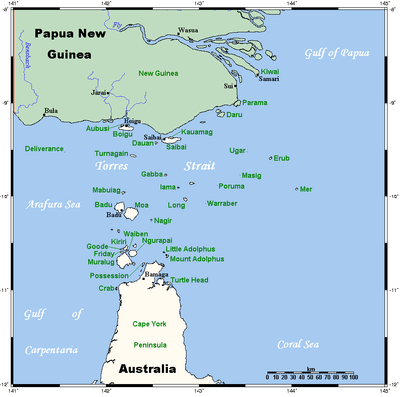

A map of the Torres Strait Islands showing Masig in the north-eastern waters of Torres Strait | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Northern Australia |

| Coordinates | 9°44′42″S 143°26′2.4″E |

| Archipelago | Torres Strait Islands |

| Adjacent bodies of water | Torres Strait |

| Length | 2.7 km (1.68 mi) |

| Width | 0.8 km (0.5 mi) |

| Administration | |

| State | Queensland |

| Local government area | Torres Strait Island Region |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 238 (2011 census)[1] |

| Ethnic groups | Torres Strait Islanders |

The Masigalgal people, of the Kulkulgal nation of the Central Torres Strait,are recognised as the traditional owners of Masig. They are of Melanesian origin and had followed traditional patterns of hunting, fishing, agriculture and trade for many thousands of years prior to contact with the first European visitors to the region.

The Queensland Government moved the people of Aureed to Masig after it was declared an Aboriginal reserve. Luggers owned by Masig families continued to operate until the pearling and shell industry collapsed in the 1960s. The people then shifted successfully into commercial mackerel fishing, prawning and crayfishing. A highly profitable fish factory has operated on the island since the late 1970s, freezing the catch and air freighting it to southern markets.

Geography

Masig/Yorke Island lies northeast of Coconut/Poruma Island in the central island group and southwest of Stephens/Ugar Island, and Darnley/Erub Island, and northwest of Murray/Mer Island in the eastern island group. It is about 160 kilometres (99 mi) northeast of Thursday Island.[2]

The island is about 2.7 kilometres (1.7 mi) long and 0.8 kilometres (2,600 ft) at its widest point,[3] a very small low-lying coral cay. The topography is very flat, with ground level generally less than 3 metres (9.8 ft) above sea level. More than half the island is covered in undisturbed vegetation, including dense trees on the eastern and western parts of the Island.[2]

History

The Masigalgal people, of the Kulkulgal nation of the Central Torres Strait,[2] are recognised as the traditional owners of Masig.[4]

The Torres Strait Islander people of Masig are of Melanesian origin and had followed traditional patterns of hunting, fishing, agriculture and trade for many thousands of years prior to contact with the first European visitors to the region.[5][6] They are skilled navigators with a detailed knowledge of the reefs and have always occupied a central position in the Straits trading networks.[3]

In September 1792, Captain William Bligh, in charge of the British Navy ships Providence and Assistant, visited Torres Strait and mapped the main reefs and channels.

In the 1860s, beche-de-mer (sea cucumber) and pearling boats began working the reefs of Torres Strait. William Banner established a beche-de-mer station at Warrior Island in 1863 and employed Islander men from Masig to work on his boats as divers and crew.[7]

Before the arrival of teachers from the London Missionary Society in the 1870s, Masig was attracting a diverse community of immigrants, some brought by the pearl and trochus shell industry.

In 1872, the Queensland Government sought to extend its jurisdiction and requested the support of the British Government.[8] Letters Patent were issued by the British Government in 1872 creating a new boundary for the colony which encompassed all islands within a 60 nautical mile radius of the coast of Queensland.[9] This boundary was further extended by the Queensland Coast Islands Act 1879 (Qld) [10][11] and included the islands of Boigu, Erub, Mer and Saibai, which lay beyond the previous 60 nautical mile limit. The new legislation enabled the Queensland Government to control and regulate bases for the beche-de-mer and pearling industries, which previously had operated outside its jurisdiction.[12]

In 1871, an American whaler from Boston named Edward (Ned) Mosby arrived in Torres Strait. He was commonly known as "Yankee Ned". After working for Frank Jardine on Nagir Island, Edward Mosby established a beche-de-mer station on Yorke in the late 1870s, with his business partner Jack Walker. Mosby and Walker leased half the island from the Queensland Government for their business operations.[13][14][15][16]

Captain Charles Pennefather, in charge of the government survey vessel Pearl, visited Masig in September 1882. Mosby and Walker lodged a complaint with Pennefather against the crew of the beche-de-mer operator Captain Walton, for cutting down Wongai fruit trees on the island for fuel.[17][18] Steam powered ships often stopped at Masig to collect supplies of firewood, resulting in deforestation on the Island.[19]

Torres Strait Islanders refer to the arrival of London Missionary Society (LMS) missionaries in July 1871 as "the Coming of the Light".The Reverend A W Murray and William Wyatt Gill were the first LMS missionaries to visit Masig in 1872.[20][21][22] Around 1900, the LMS missionary the Reverend Walker established a philanthropic business scheme named Papuan Industries Limited. This company encouraged Islander communities to co-operatively rent or purchase their own pearl luggers or "company boats". The company boats, were used to harvest pearl shells and beche-de-mer, which was sold and distributed by the company.

The people of Masig purchased their first company boats around 1905. These boats provided Islanders with income, a sense of community pride and also improved transport and communication between the islands.[23] ‘Yankee,’ Ned Mosby’s son, also operated a number of pearl luggers from Masig, including the Yano and Nancy.[24]

In November 1912, the Queensland Government officially gazetted 320 acres of land on Masig as an Aboriginal reserve. Many other Torres Strait Islands were gazetted as Aboriginal reserves at the same time.[25] The Government moved the people of Aureed to Masig after this.

A government school was established on the island in 1912.[26][27] By 1918, a Protector of Aboriginals had been appointed to Thursday Island and, during the 1920s and 1930s, racial legislation was strictly applied to Torres Strait Islanders, enabling the government to remove Islanders to reserves and missions across Queensland.

A world-wide influenza epidemic reached the Torres Strait in 1920, resulting in 96 deaths in the region. The Queensland Government provided the islands of Masig, Iama and Poruma with food relief to help them recover from the outbreak.[28][29] In March 1923, Masig and Poruma were hit by a "violent hurricane" which destroyed local crops and gardens.[30] The Queensland Government subsequently established new facilities on Masig during the 1930s, including an Aboriginal Industries Board store, a court house, and improved roads.[31][32][33][34]

In 1936, around 70% of the Torres Strait Islander workforce went on strike in the first organised challenge against government authority made by Torres Strait Islanders. The nine-month strike was an expression of Islanders’ anger and resentment at the increasing government control of their livelihoods. The strike was a protest against government interference in wages, trade and commerce and also called for the lifting of evening curfews, the removal of the permit system for inter-island travel and the recognition of the Islanders’ right to recruit their own boat crews.[35][36]

This strike produced a number of significant reforms and innovations. Unpopular local Aboriginal Protector J.D. McLean was removed and replaced by Cornelius O’Leary, who established a system of regular consultations with elected islander council representatives. The new island councils were given a degree of autonomy, including control over local island police and courts.[37]

On 23 August 1937, O’Leary convened the first Inter Islander Councillors Conference at Masig. Representatives from 14 Torres Strait communities attended. Barney Mosby, Dan Mosby and William represented Masig at the conference. After lengthy discussions, unpopular bylaws, including the evening curfews, were cancelled and a new code of local representation was agreed upon.[38][39][40]

In 1939 the Queensland Government passed the Torres Strait Islander Act 1939, which incorporated many of the recommendations discussed at the conference. A key section of the new act officially recognised Torres Strait Islanders as a separate people from Aboriginal Australians.[41][42]

During World War Two, the Australian Government recruited Torres Strait Islander men to serve in the armed forces. Enlisted men from Masig and other island communities formed the Torres Strait Light Infantry. While the Torres Strait Light Infantry were respected as soldiers, they only received one third of the pay given to white Australian servicemen. On 31 December 1943, members of the Torres Strait Light Infantry went on strike, calling for equal pay and equal rights.[43] The Australian Government agreed to increase their pay to two thirds the level received by white servicemen. Full back pay was offered in compensation to the Torres Strait servicemen by the Australian Government in the 1980s.[44][45]

Following World War Two, the pearling industry declined across Torres Strait and Islanders were permitted to work and settle on the Australian mainland. Prawning and fishing enterprises were established at Masig in the 1970s. Luggers owned by Masig families continued to operate until the collapse of the pearl industry in the 1960s, after which the people shifted successfully into commercial mackerel fishing, prawning and crayfishing.[46][47]

In December 1978, a treaty was signed by the Australian and Papua New Guinea governments that described the boundaries between the two countries and the use of the sea area by both parties. The Torres Strait Treaty, which commenced operation in February 1985, contains special provision for free movement (without passports or visas) between both countries.[48] Free movement between communities applies to traditional activities such as fishing, trading and family gatherings which occur in a specifically created Protected Zone and nearby areas.[49]

Governance

On 30 March 1985, the Masig community elected 3 councillors to constitute an autonomous Masig Island Council established under the Community Services (Torres Strait) Act 1984. This Act conferred local government-type powers and responsibilities upon Torres Strait Islander councils. The council area, previously an Aboriginal reserve held by the Queensland Government, was transferred on 21 October 1985 to the trusteeship of the council under a Deed of Grant in Trust (DOGIT).[50][51]

Native title was recognised over Masig in 2000,[52] held in trust by the Masigalgal (Torres Strait Islander) Corporation RNTBC.[2]

In 2007, the Local Government Reform Commission recommended that the 15 Torres Strait Island councils be abolished and the Torres Strait Island Regional Council be established. The first Torres Strait Island Regional Council was elected on 15 March 2008 in elections conducted under the Local Government Act 1993.[53]

Facilities

A regular scheduled air service is operated by West Wing Aviation from Horn Island, otherwise access to Masig is by charter plane or boat. All goods and mail are delivered by a weekly barge service and via the scheduled air service. Masig has a medical centre, staffed by a qualified nurse and there is also a doctor based there, who provides medical services to three other islands in the central island cluster (Coconut, Yam and Warraber). The island has a school, which is a campus of Tagai State College (based on Thursday Island). There is an IBIS store on the island and also a Mini-Mart.

Popular culture

Yorke Island was the film location for the Australian television series, RAN Remote Area Nurse.

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (31 October 2012). "Masig Island". 2011 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- "Masig calendar - Indigenous Weather Knowledge". Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- "Masig". Torres Strait Islands Regional Council. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- Masig People v the State of Queensland [2000] FCA 1067.

- R E Johannes & J W MacFarlane, Traditional Fishing in the Torres Strait Islands(CSIRO, 1991) 115-143

- M Fuary, In So Many Words: An Ethnography of Life and Identity on Yam Island, Torres Strait (PhD Thesis, James Cook University, Townsville, 1991) 68-71.

- R Ganter, The Pearl Shellers of Torres Strait (Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1994) 19-20.

- S B Kaye, Jurisdictional Patchwork: Law of the Sea and Native Title Issues in the Torres Strait (2001) 2, Melbourne Journal of International Law, 1.

- Queensland, Queensland Statutes (1963) vol 2, 712.

- See also Colonial Boundaries Act 1895 (Imp)

- Wacando v Commonwealth(1981) 148 CLR 1.

- S Mullins, Torres Strait, A History of Colonial Occupation and Culture Contact 1864-1897 (Central Queensland University Press, Rockhampton, 1994) 139-161.

- R Ganter, The Pearl Shellers of Torres Strait (Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1994), 27-28, 247

- J Foley, Timeless Isle, An Illustrated History of Thursday Island (Torres Strait Historical Society, Thursday Island, 2003) 3

- S Mullins, Torres Strait, A History of Colonial Occupation and Culture Contact 1864-1897 (Central Queensland University Press, Rockhampton, 1994), 169.

- "DEATH OF "YANKEE NED."". Evening News (13, 802). New South Wales, Australia. 2 September 1911. p. 8. Retrieved 19 July 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- Queensland State Archives, Colonial Secretary’s Correspondence, COL/A349, 1882/5869

- N Sharp, Stars of Tagai, The Torres Strait Islanders (Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 1993) 26.

- M Fuary, In So Many Words: An Ethnography of Life and Identity on Yam Island, Torres Strait (PhD Thesis, James Cook University, Townsville, 1991), 145

- R Ganter, The Pearl Shellers of Torres Strait (Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1994) 68-75

- Queensland, Annual Report of the Chief Protector of Aboriginals for 1905 (1906) 29

- N Sharp, Stars of Tagai, The Torres Strait Islanders (Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 1993), 158-161.

- S Mullins, Torres Strait, A History of Colonial Occupation and Culture Contact 1864-1897 (Central Queensland University Press, Rockhampton, 1994), 121

- Queensland, Annual Report of the Chief Protector of Aboriginals for 1916 (1917) 9.

- Queensland, Queensland Government Gazette, vol.99, no.138 (1912) 1330.

- Queensland, Annual Report of the Chief Protector of Aboriginals for 1912(1913) 21

- Queensland, Annual Report of the Chief Protector for 1913 (1914) 13.

- Queensland, Annual Report of the Chief Protector of Aboriginals for 1920(1921) 7

- M Fuary, In So Many Words: An Ethnography of Life and Identity on Yam Island, Torres Strait (PhD Thesis, James Cook University, Townsville, 1991), 148.

- Queensland, Annual Report of the Chief Protector of Aboriginals for 1923(1924) 6.

- Queensland, Annual Report of the Chief Protector of Aboriginals for 1932(1933) 13

- N Sharp, Stars of Tagai, The Torres Strait Islanders (Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 1993), 184

- Queensland, Annual Report of the Chief Protector of Aboriginals for 1931 (1932), 9

- Queensland, Annual Report of the Department of Native Affairs for 1938 (1939) 14.

- N Sharp, Stars of Tagai, The Torres Strait Islanders (Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 1993), 181-186, 278

- Beckett, Torres Strait Islanders: Custom and Colonialism (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; 1987)

- Beckett, Torres Strait Islanders: Custom and Colonialism (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; 1987), 54-55.

- N Sharp, Stars of Tagai, The Torres Strait Islanders (Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 1993), 210-214

- Queensland, Annual Report of the Department of Native Affairs for 1937 (1938) 13

- Queensland State Archives, A/3941 Minutes of Torres Strait Councillors Conference held at Yorke Island 23–25 August 1937.

- Sections 3 (a) – (c) of the Torres Strait Islander Act (Qld) 1939. See also the Queensland, Annual Report Department of Native Affairs for 1939 (1940) 1

- N Sharp, Stars of Tagai, The Torres Strait Islanders (Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 1993), 214-216.

- Australian War Memorial website, Wartime Issue 12 ‘One Ilan Man’, http://www.awm.gov.au/wartime/12/article.asp.

- Beckett, Torres Strait Islanders: Custom and Colonialism (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; 1987), 64-65

- Australian War Memorial website, Wartime Issue 12 ‘One Ilan Man’, http://www.awm.gov.au/wartime/12/article.asp.

- Beckett, Torres Strait Islanders: Custom and Colonialism (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; 1987), 182

- R E Johannes & J W MacFarlane, Traditional Fishing in the Torres Strait Islands(CSIRO, 1991), 117-118.

- Under Art. 11.

- See also Art 12.

- Queensland, Annual Report of the Department of Community Services for 1986(1987) 3

- Queensland, Annual Report of the Department of Community Services for 1987 (1988) 29.

- "Masigalgal (Torres Strait Islanders) Corporation RNTBC". PBC. 15 May 2000. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- In the elections conducted under the Local Government Act 1993 members of the 15 communities comprising the TSIRC local government area each voted for a local councillor and a Mayor to constitute a council consisting of 15 councillors plus a mayor.

Attribution

This Wikipedia article contains material from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community histories: Yorke Island (Masig). Published by The State of Queensland under CC-BY-4.0, accessed on 3 July 2017.