Washington Union Station

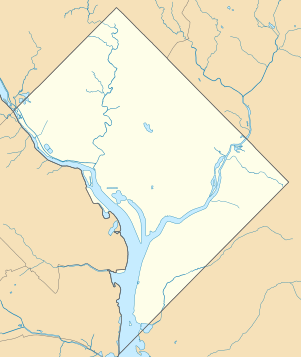

Washington Union Station is a major train station, transportation hub, and leisure destination in Washington, D.C. Opened in 1907, it is Amtrak's headquarters and the railroad's second-busiest station with annual ridership of just under 5 million[5] and the ninth-busiest in overall passengers served in the United States. The station is the southern terminus of the Northeast Corridor, an electrified rail line extending north through major cities including Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York City, and Boston and the busiest passenger rail line in the nation.

Union Station Washington, DC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amtrak, MARC, and VRE railway station | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | 50 Massachusetts Avenue NE Washington, DC United States | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 38°53′50″N 77°00′23″W | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owned by | Washington Terminal Company and USDOT[1] Union Station Redevelopment Corp. leased to Ashkenazy Acquisition Corporation[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operated by | Jones Lang LaSalle | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line(s) | Northeast Corridor RF&P Subdivision | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Platforms | 18 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tracks | 22 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Train operators | Amtrak, MARC, VRE | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bus stands | located on the mezzanine level[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bus operators |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Connections | Washington Metro at Union Station | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Construction | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parking | 2,448 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bicycle facilities | 180 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Disabled access | Yes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other information | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Station code | Amtrak code: WAS IATA code: ZWU | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fare zone | 1(VREX) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | 1908 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rebuilt | 1981–1989 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traffic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Passengers (2017) | 5,225,460 annually[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Services | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Washington D.C. Union Station | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Built | 1908 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Architect | D.H. Burnham & Company (William Pierce Anderson, Daniel Burnham) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Architectural style | Classical, Beaux-Arts, among others | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| NRHP reference No. | 69000302 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Designated | March 24, 1969 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

An intermodal facility, Union Station also serves MARC and VRE commuter rail services, the Washington Metro, the DC Streetcar, intercity bus lines, and local Metrobus buses.

At the height of its traffic, during World War II, as many as 200,000 passengers passed through the station in a single day.[6] In 1988, a headhouse wing was added and the original station renovated for use as a shopping mall. Today, Union Station is one of the busiest rail facilities and shopping destinations in the United States, and is visited by over 40 million people a year.[7]

History

Pre-Union Station terminals

Before Union Station opened, each of the major railroads operated out of one of two stations:

- New Jersey Avenue Station (1851–1907): Baltimore and Ohio Railroad trains arrived and left from this railroad station. It was located at the corner of New Jersey Avenue NW and C Street NW.[8]

- Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station (1872–1907): Baltimore and Potomac Railroad (B&P) (a subsidiary of the Pennsylvania Railroad), the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway, and the Southern Railway all left from this train station. It was located at the corner of B Street NW (now Constitution Avenue) and 6th Street NW.[8]

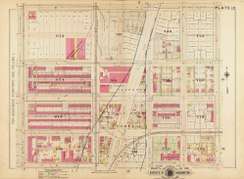

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad line ran east on D Street NE across North Capitol, then north on Delaware Avenue NE. It divided into two lines. The Metropolitan branch continued north on 1st Street NE, turning east on New York Ave NE and continuing north through Eckington. The other line turned east onto I Street NE up to 7th Street NE where it headed back north on what is today West Virginia Avenue running next to the Columbia Institution for the Deaf and Dumb now Gallaudet University.[9]

Construction

When the Pennsylvania Railroad and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad announced in 1901 that they had agreed to build a new union station together, the city had two reasons to celebrate.[10] The decision meant that both railroads would soon remove their trackwork and terminals from the National Mall. Though changes there appeared only gradually, the consolidation of the depots allowed the creation of the Mall as it appears today. Secondly, the plan to bring all the city's railroads under one roof promised that Washington would finally have a station both large enough to handle large crowds and impressive enough to befit the city's role as the federal capital. The station was to be designed under the guidance of Daniel Burnham, a famed Chicago architect and member of the U.S. Senate Park Commission, who in September 1901 wrote to the Commission's chairman, Sen. James McMillan, of the proposed project: "The station and its surroundings should be treated in a monumental manner, as they will become the vestibule of the city of Washington, and as they will be in close proximity to the Capitol itself."[11]

After two years of complicated and sometimes contentious negotiations, Congress passed S. 4825 (58th-1st session) entitled "An Act to provide a union railroad station in the District of Columbia" which was signed into law by 26th President Theodore Roosevelt on February 28, 1903.[12] The Act authorized the Washington Terminal Company (which was to be jointly owned by the B&O and the PRR-controlled Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington Railroad) to construct a station "monumental in character" that would cost at least $4 million. (The main station building's actual cost eventually exceeded $5.9 million.) Including additional outlays for new terminal grades, approaches, bridges, viaducts, coach and freight yards, tunnels, shops, support buildings and other infrastructure, the total cost to the Terminal Company for all the improvements associated with Union Station exceeded $16 million. This cost was financed by $12 million in first mortgage bonds as well as advances by the owners which were repaid by stock and cash.

Each carrier also received $1.5 million in government funding to compensate them for the costs of eliminating grade crossings in the city. The only railroad station in the nation specifically authorized by the U.S. Congress, the building was primarily designed by William Pierce Anderson of the Chicago architectural firm of D.H. Burnham & Company.[13][14]

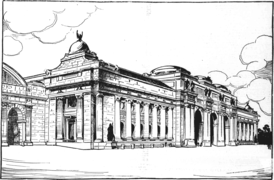

A 1902 drawing of a proposal for the design of Union Station

A 1902 drawing of a proposal for the design of Union Station Union Station in 1906 before its opening. Notice the absence of the Columbus Fountain

Union Station in 1906 before its opening. Notice the absence of the Columbus Fountain Statue of Thales representing electricity being hoisted up

Statue of Thales representing electricity being hoisted up

Impact on the neighborhood

Though the project was supported on the Federal level, there was opposition at the local level. The new depot would displace residents and impact the new neighborhoods east of the tracks.

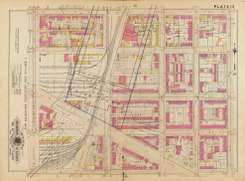

On January 10, 1902, a meeting took place between the representatives of the railroads and those of the District of Columbia to present preliminary plans regarding the construction of the Union Depot (Union Station). The plan proposed creating tunnels under the tracks for K, L and M Street NE but that H Street would be closed. The street would be closed 300 feet (91 m) on both sides of Delaware Avenue (for a total of 600 feet (180 m)). If a tunnel was to be built for H Street NE, the cost would be an extra $10,000.[15]

On January 13, 1902, the Northeast Washington Citizens' Association meeting at the Northeast Temple on H Street NE was outraged over this plan. Representatives of Congress and the Railroads were present to hear the opposition of the citizens present. The president of the Association that the Pennsylvania Railroad controlled Congress and a member of the Association threatened to take them to court. The loss of a major access road to downtown for the residents of Northeast, the loss of millions of dollars of business properties and of the business it represents, the closure of a vital streetcar line used by commuters was unacceptable considering the cost of building an access across the tracks.[16]

At the March 10, 1902 meeting, the President of the Association informed the audience that the District Commissioners was supportive of requests of the citizens of Washington, DC and that H Street would remain open with a 750 ft tunnel running under the tracks.[17]

The Station and tracks took the place of over 100 houses in the heart of an impoverished neighborhood called "Swampoodle" where crime was rampant. It was the end of a community but the beginning of a new era for Washington, DC. Tiber Creek, which was prone to flooding, was put in a tunnel. Delaware Avenue disappeared from the map between Massachusetts Avenue and Florida Avenue under the tracks. Only a small section remains next to the tracks between L and M Streets NE.[18]

Map showing the impact of the railway tracks

Map showing the impact of the railway tracks Map showing the impact of Union Station

Map showing the impact of Union Station

Opening and operation

The first B&O train to arrive with passengers was the Pittsburgh Express, which did so at 6:50 a.m. on October 27, 1907, while the first PRR train arrived three weeks later on November 17. The main building itself was completed in 1908. Of its 32 station tracks, 20 enter from the northeast and terminate at the station's headhouse. The remaining 12 tracks enter below ground level from the south via a 4,033-foot twin-tube tunnel passing under Capitol Hill and an 898-foot long subway under Massachusetts Avenue which allow through traffic direct access to the rail networks both north and south of the city.[19][20][21][22]

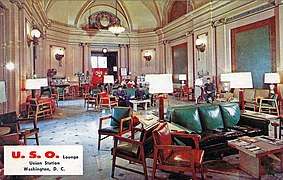

Among the new station's unique features was an opulent "Presidential Suite" (aka "State Reception Suite") where the U.S. President, State Department, and Congressional leaders could receive distinguished visitors arriving in Washington. Provided with a separate entrance, the suite (which was first used by 27th President William Howard Taft in 1909) was also meant to safeguard the Chief Executive during his travels in an effort to prevent a repeat of the July 1881 assassination of 20th President James A. Garfield in the old former Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station.[22][23] The suite was converted in December 1941, during World War II to a U.S.O. (United Services Organization) canteen, which went on to serve 6.5 million military service members during World War II. Although closed on May 31, 1946, it was reopened in 1951 as a U.S.O. lounge and dedicated by President Harry Truman as a permanent "home away from home" for traveling U.S. Armed Services members.[24][25]

On the morning of January 15, 1953, the Pennsylvania Railroad's Federal, the overnight train from Boston, crashed into the station. When the engineer tried to apply the trainline brakes two miles out of the platforms, he discovered that he only had engine brakes. A switchman on the approach to the station noticed the runaway train and telephoned a warning to the station, as the train coasted downhill into track 16. The GG1 locomotive, No. 4876, hit the bumper block at about 35 miles per hour (56 km/h), jumped onto the platform, destroyed the stationmaster's office at the end of the track, took out a newsstand, and was on its way to crashing through the wall into the Great Hall. Just then, the floor of the terminal, having never been designed to carry the weight of a locomotive, gave way, dropping the engine into the basement. The 447,000-pound (202,800 kg) electric locomotive fell into about the center of what is now the food court. Remarkably, no one was killed, and passengers in the rear cars thought that they had only had a rough stop. An investigation revealed that an anglecock on the brakeline had been closed, probably by an icicle knocked from an overhead bridge. The accident inspired the finale of the 1976 film Silver Streak.[26] The durable design of the GG1 made its damage repairable, and it was soon back in service after being hauled away in pieces to the PRR's main shops in Altoona, Pennsylvania. Before the latter action was undertaken, however, the GG1 and the hole it made were temporarily planked over and hidden from view due to the imminent inauguration of General Dwight D. Eisenhower as the thirty-fourth President of the United States.

Until intercity passenger rail service was taken over by Amtrak in 1971, Union Station served as a hub for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, Chesapeake and Ohio Railway, Pennsylvania Railroad, and Southern Railway. The Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac Railroad provided a link to Richmond, Virginia, about 100 miles (161 km) to the south, where major north–south lines of the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad and Seaboard Air Line Railroad provided service to the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida.[27] World War II was the busiest period in the station's history in terms of passenger traffic with up to 200,000 people passing through on a single day.[6]

Trains at the station shortly after its completion, circa 1908

Trains at the station shortly after its completion, circa 1908 Train concourse, circa 1915

Train concourse, circa 1915 U.S.O. Lounge (former Presidential Suite)

U.S.O. Lounge (former Presidential Suite)

Decline

In 1967, the chairman of the Civil Service Commission expressed interest in using Union Station as a visitor center during the upcoming Bicentennial celebrations. Funding for this was collected over the next six years, and the reconstruction of the station included outfitting the Main Hall with a recessed pit to display a slide show presentation. This was officially the PAVE (Primary Audio-Visual Experience), but was sarcastically referred to as "the Pit". The entire project was completed, save for the parking garage, and opening ceremonies were held on Independence Day 1976. Due to a lack of publicity and convenient parking, the National Visitor Center was never popular. Financial considerations caused the National Park Service to close the theaters, end the slideshow presentation in "the Pit", and lay off almost three-quarters of the center's staff on October 28, 1978.[28]

After the leaking roof caused the partial collapse of plaster from the ceiling in the eastern wing of the building, the National Park Service declared the entire structure unsafe on February 23, 1981, and sealed the structure to the public.[29]

Restoration

The 1981 ceiling collapse deeply alarmed members of Congress and officials in the new Reagan administration. On April 3, despite a budget austerity push, administration officials proposed a plan to appropriate $7 million to allow the Department of the Interior to finish its authorized $8 million roof repair program. In addition, the government of the District of Columbia would be permitted to reprogram up to $40 million in federal highway money to finish the parking garage at Union Station.[30] On October 19, administration officials and members of the United States Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation agreed on additional aspects of the plan. Up to $1 million would be authorized and appropriated to fund a study on needed repairs at the station and a second study on the feasibility of turning Union Station into a retail complex. The Department of Transportation (DOT) was authorized to sign contracts with any willing corporation to construct a retail complex in and around Union Station.[31] DOT was also authorized to spend up to $29 million in already-appropriated money from its Northeast Corridor rail capital building program on Union Station repairs.[32] The revised bill also required DOT to take control of Union Station from the Department of the Interior,[31] and for DOT to buy out its lease with the station's private-sector owners. The buy-out would be spread over six years, for which $275,000 a year was authorized and appropriated.[32] The bill required DOT to operate Union Station as a train station once more, complete with ticketing, waiting areas, baggage areas, and boarding. Although no statement was made in the bill, Senate aides said the intent was to have Amtrak tear down its 1960s-era station at the rear of Union Station and move its operations back inside.[31] The Senate passed the bill unanimously on November 23.[33] The House approved the bill on December 16.[32] President Ronald Reagan signed the Union Station Redevelopment Act into law on December 29.[34][35]

As a result of the Redevelopment Act of 1981, Union Station was closed for restoration and refurbishing. Mold was growing in the leaking ceiling of the Main Hall, and the carpet laid out for an Inauguration Day celebration was full of cigarette-burned holes. In 1988, Secretary of Transportation Elizabeth Dole awarded $70 million to the restoration effort. "The Pit" was transformed into a new basement level, and the Main Hall floor was refitted with marble. While installing new HVAC systems, crews discovered antique items in shafts that had not been opened since the building's creation.

A new life

The station reopened in its present form on September 29, 1988.[36] The former "Pit" area was replaced with an AMC movie theater (later Phoenix Theatres), which closed on October 12, 2009, and was replaced with an expanded food court and a Walgreens store. The food court still retains the original arches under which the trains were parked as well as the track numbers on those arches. A variety of shops opened along the Concourse and Main Hall, and a new Amtrak terminal at the back behind the original Concourse. Trains no longer enter the original Concourse but the original, decorative gates were relocated to the new passenger concourse. In 1994, this new passenger concourse was renamed to honor W. Graham Claytor, Jr., who served as Amtrak's president from 1982 to 1993. The decorative elements of the station were also restored. The skylights were preserved, but sunlight no longer illuminates the Concourse because it is blocked by the newer roof structure built directly overhead to support the aging, original structure.

In June 2015, the Union Station Redevelopment Corporation released the first ever Historic Preservation Plan to guide future preservation and restoration efforts at the Washington Union Station complex.[37]

In January 2017, the expansion and refurbishment of the Washington Union Station was listed as one of the priority infrastructure projects of the Donald Trump administration at an estimated cost of $8.7 billion.[38]

Architecture

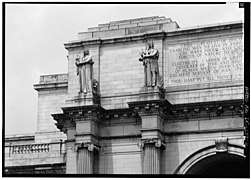

Architect Daniel H. Burnham, assisted by Pierce Anderson, was inspired by a number of architectural styles. Classical elements included the Arch of Constantine (exterior, main façade) and the great vaulted spaces of the Baths of Diocletian (interior); prominent siting at the intersection of two of Pierre (Peter) Charles L'Enfant's avenues, with an orientation that faced the United States Capitol just five blocks away; a massive scale, including a façade stretching more than 600 ft (180 m) and a waiting room ceiling 96 ft (29 m) above the floor; stone inscriptions and allegorical sculpture in the Beaux-Arts style; expensive materials such as marble, gold leaf, and white granite from a previously unused quarry.

In the Attic block, above the main cornice of the central block, stand six colossal statues (modeled on the Dacian prisoners of the Arch of Constantine) created by Louis St. Gaudens. These are entitled "The Progress of Railroading" and their iconography expresses the confident enthusiasm of the American Renaissance movement:

- Prometheus (for Fire)

- Thales (for Electricity)

- Themis (for Freedom and Justice)

- Apollo (for Imagination and Inspiration)

- Ceres (for Agriculture)

- Archimedes (for Mechanics)

Prometheus (Fire)

Prometheus (Fire) Thales (Electricity)

Thales (Electricity) Themis (Freedom and Justice)

Themis (Freedom and Justice) Ceres (Agricul-ture)

Ceres (Agricul-ture)- Archimedes (Mechanics)

The substitution of Agriculture for Commerce in a railroad station iconography vividly conveys the power of a specifically American lobbying bloc.

St. Gaudens also created the 26 centurions for the station's main hall.

Burnham drew upon a tradition, launched with the 1837 Euston railway station in London, of treating the entrance to a major terminal as a triumphal arch. He linked the monumental end pavilions with long arcades enclosing loggias in a long series of bays that were vaulted with the lightweight fireproof Guastavino tiles favored by American Beaux-Arts architects. The final aspect owed much to the Court of Heroes at the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, where Burnham had been coordinating architect. The setting of Union Station's façade at the focus of converging avenues in a park-like green setting is one of the few executed achievements of the City Beautiful movement: elite city planning that was based on the "goosefoot" (patte d'oie) of formal garden plans made by Baroque designers such as André Le Nôtre.

The station held a full range of dining rooms and other services, including barber shops and a mortuary. Union Station was equipped with a presidential suite which is now occupied by a restaurant.

Services

Today Union Station is again one of Washington's busiest and best-known places, visited by 40 million people each year and has many shops, cafes, and restaurants.[39]

Union Station is served by Amtrak's high-speed Acela Express, Northeast Regional, and several of Amtrak's long-distance trains (including, among others, the Capitol Limited, Crescent, and Silver Service trains). From Union Station, Amtrak also operates long-distance service to the Southeast and Midwest, including many intermediate stops to destinations such as Chicago, Charlotte, New Orleans, and Miami. In fiscal 2011, an average of more than 13,000 passengers boarded or got off Amtrak trains each day.[5] It is also the busiest station that can handle the railroad's Superliner railcars; inadequate tunnel clearances in Baltimore and New York preclude the use of Superliners on most Eastern routes.[40]

The station is also the terminus for the MARC and Virginia Railway Express commuter railways, linking Washington to Maryland and West Virginia (MARC) and Northern Virginia (VRE). A nearby Washington Metro station connects to the Red Line.

The station's tracks are split between a ground level and a lower level. The ground level contains tracks 7–20 (tracks 1-6 no longer exist), which are served by high-level bay platforms at the door level of most trains. These tracks are used by all MARC commuter rail services, all Amtrak Acela Express trains, the Amtrak Capitol Limited, and Amtrak Northeast Regional trains that terminate at the station. All of the tracks on this level terminate at the station and are only used by trains arriving from and departing to the north.

The lower level contains tracks 22–29, which are served by low-level platforms at the track level. These platforms are served by all VRE trains, all Amtrak long-distance trains that serve the station except for the Capitol Limited, and Amtrak Northeast Regional trains that continue south to Virginia. Unlike the tracks on the upper level, the lower level tracks run through under the station building and Capitol Hill via the First Street tunnel. Electrification ends at the station, and all trains continuing south through the tunnel must have their electric engines swapped out for diesel locomotives. For example, when a southbound Northeast Regional train arrives on a lower level platform on its way to Newport News, Virginia, its Siemens ACS-64 electric engine is removed and set aside. A GE Genesis diesel engine that was earlier removed from a northbound train is coupled to the front of the southbound, and it continues through the tunnel toward Virginia. The ACS-64 is readied for a Northeast Regional arriving from Alexandria, and once coupled pulls the train toward Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York or Boston.

The Metrorail station is underground beneath the western side of the building. Entrances are located inside Union Station with direct access from the high-level MARC and Amtrak platforms, from the east side of First Street NE, or from just outside the station at Massachusetts Avenue NE, providing access to the main concourse.[41]

On August 1, 2011, John Porcari, the United States Deputy Secretary of Transportation, announced that Union Station would begin serving intercity buses operated by Greyhound Lines, BoltBus, Megabus, and Washington Deluxe later that year from a new bus facility in the station's parking garage.[42] By November 15, 2011, BoltBus, Megabus, Tripper Bus, and Washington Deluxe were operating from the new facility.[43] On September 26, 2012, Greyhound and Peter Pan Bus Lines relocated all of their Washington, D.C., operations to the facility.[44] Buses of the Georgetown-Union Station route of the DC Circulator system stop within the facility every ten minutes during operating hours.[45] As of 2017, OurBus now services Union Station, providing routes to Maryland, New Jersey, and New York.

The DC Streetcar's H Street/Benning Road Line serves the station from a stop on the H Street Bridge (a.k.a. the "Hopscotch Bridge") directly north of the station. The stop is accessible via the station's parking garage.[46]

Columbus Circle has been rebuilt to address the severely deteriorated roadbed, realign the passenger pickup/dropoff locations, streamline the taxi stand, and to better accommodate the popular tour bus attractions.

The Ivy City Yard, just north of Union Station, houses a large Amtrak maintenance facility. This includes the new maintenance facility for the Acela high-speed train sets. Amtrak also does contract work for MARC's electric locomotives. Metro's Brentwood maintenance facility is also in the southwest corner of the Ivy City Yard. Riders on the Metro Red Line between Union Station and Rhode Island Avenue Station get an aerial view of the south end of the Ivy City Yard.

Owner

Union Station is owned by the Washington Terminal Company and United States Department of Transportation. The DOT owns the station building itself and the surrounding parking lots, while WTC, a nearly wholly owned subsidiary of Amtrak (99.9% controlling interest), owns the platforms and tracks.[1][47]

The non-profit Union Station Redevelopment Corporation managed the station on behalf of the owners, but an 84-year lease of the property is held by New York-based Ashkenazy Acquisition Corporation and managed by Chicago-based Jones Lang LaSalle.[48] Its offices used to house the headquarters of Amtrak (until 2017) and carries the IATA airport code of ZWU.[49]

In July 2012, Amtrak announced a four-phase, $7 billion plan to revamp and renovate the station over 15 to 20 years. The proposed conversion would "double the number of trains and triple the number of passengers in gleaming, glass-encased halls". Former Amtrak President and CEO Joseph H. Boardman hoped the federal government would finance "50 to 80 percent" of the project.[50]

Gallery

.tiff.jpg) Interior, Waiting Room ca. 1915

Interior, Waiting Room ca. 1915 Union Station's interior waiting room.

Union Station's interior waiting room. Interior of Union Station train concourse from West

Interior of Union Station train concourse from West South Front Entrance, 1968

South Front Entrance, 1968 Detail of the west end of the main entrance pavilion, showing statuary and inscription

Detail of the west end of the main entrance pavilion, showing statuary and inscription

See also

- Union Station (disambiguation)

- Freedom Bell, American Legion located in front of Union Station.

- List of busiest railway stations in North America

Notes

- "Washington – Union Station, DC (WAS)". the Great American Stations. Amtrak. 2016.

- "Union Station". Ashkenazy Acquisition Corporation. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- "Washington, D.C. STATION". Peter Pan. Peter Pan Bus Lines. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- "Amtrak Fact Sheet, FY2017, District of Columbia" (PDF). Amtrak. November 2017. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- "Amtrak National Fact Sheet: FY2015" (PDF). Amtrak. July 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- "Union Station". Washington, DC: A National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary. National Park Service. Retrieved February 18, 2015. See Talk for more discussion of this daily traffic number.

- "The World's Most-visited Tourist Attractions". Travel+Leisure. Time Inc. Affluent Media Group. November 10, 2014.

- Union Station Opening: Railroad Officials Decide on Dates for Using Terminal – The Washington Post – October 8, 1907 – page 2

- Sanborn Map of Washington DC, 1903–1916 Vol. 2

- Wright, William (2006). Now Arriving Washington: Union Station and Life in the Nation's Capital (PDF). p. 54.

- Moore 1921, p. 160.

- Pub.L. 57–122, S. 4825, 32 Stat. 909, enacted February 28, 1903

- Churella 2013, pp. 738; 741–745

- Burgess & Kennedy (1949), p. 499-500.

- Plans for Union Depot - January 10, 1902 - The Washington Post - page 12

- Against Union Depot: Northeast Citizens' Association Condemns Project - January 14, 1902 - The Washington Post - page 2

- Talked of Railroad Matters: Northeast Citizens' Association Discussed Proposed New Union Depot - The Washington Post - page 2

- Department of Transportation Headquarters: Environmental Impact Statement, GSA June 2000

- Burgess & Kennedy (1949), p. 500.

- Abbey, Wallace W. "Where the Nation Comes to Washington" ; track diagram. Trains & Travel Magazine, Vol XII, No, 12 (Oct., 1952). p.50-51

- S.Res. 664 "Celebrating the centennial of Union Station in Washington, District of Columbia",110th Congress, 2nd Session September 17, 2008. U.S. Government Printing Office, GPO.gov

- Churella 2013, p. 744

- Moore 1921, p. 174.

- Abbey 1952 p.51

- S.Res. 664 2008

- Cooper, Rachel. Union Station in Washington, D.C. Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing, 2011. Page 61.

- "Passenger trains operation on the eve of Amtrak" (PDF). Trains Magazine. Retrieved June 30, 2018.

- "Visitor Center Staff and Space to Be Reduced". The Washington Post. October 27, 1978. p. C1.

- Harden, Blaine (February 24, 1981). "Union Station, Leaking Badly, Closed as Unsafe". The Washington Post. p. A1.

- Eisen, Jack (April 4, 1981). "U.S. to Rescue Union Station With $48 Million". The Washington Post. p. C1.

- Burgess, John (October 20, 1981). "Rail Station Plan Gets Reagan Nod". The Washington Post. p. B1.

- Burgess, John (December 17, 1981). "Union Station Repairs Voted". The Washington Post. p. C1.

- Burgess, John (November 24, 1981). "Senate Backs Plan for Union Station". The Washington Post. p. A7.

- Pub.L. 97–125, S. 1192, 95 Stat. 1667, enacted December 29, 1981

- "Reagan Signs Measure To Aid Union Station". The Washington Post. December 30, 1981. p. C2.

- Amtrak History and Archives. Accessed March 8, 2013.

- "USRC COMPLETES HISTORIC PRESERVATION PLAN FOR WASHINGTON UNION STATION". Union Station Redevelopment Corporation. June 15, 2015. Retrieved October 20, 2017.

- "Trump makes $137bn list of "emergency" infrastructure schemes, all needing private finance". Global Construction Review. January 30, 2017. Retrieved October 13, 2019.

- "Union Station: About". Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- "VTS: Viewliner II: Amtrak's New Long-Distance Fleet". Aerospace and Electronic Systems Society. 2019.

- "Station Vicinity Map: Union Station" (PDF). WMATA. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- Thomson, Robert (2011-07-30). "Union Station to become intercity bus center". PostLocal. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2011-10-17. Retrieved 2011-08-02.

- Associated Press (2011-11-15). "Officials to inaugurate revamped bus departure zone at Washington's Union Station". PostLocal. The Washington Post. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- "Greyhound and Peter Pan Bus Lines Relocate all Washington, D.C., Service to Union Station". News Release. Dallas, Texas: Greyhound Lines. 2012-09-19. Archived from the original on 2012-11-24. Retrieved 2012-11-24.

- "Georgetown-Union Station". Bus Routes and Schedules. Washington, D.C.: DC Circulator. Archived from the original on 2012-11-08. Retrieved 2012-11-24.

- Laris, Michael (February 27, 2016). "Want to ride the D.C. streetcar? Here's a handy FAQ". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- "Amtrak Annual Report, Fiscal Year 2014" (PDF). p. 49. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- Dana, Hedgpeth (February 1, 2007). "Union Station Is Leased to N.Y. Firm for $160 Million". Washington Post. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- "LastUpDate.com - Help - Three Letter Airport Codes". www.lastupdate.com.

- "UPDATED: Here's What a Revamped D.C. Union Station Would Look Like". WNYC.

References

- Burgess, George H.; Kennedy, Miles C. (1949). Centennial History of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company. Philadelphia: The Pennsylvania Railroad Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Churella, Albert J. (2013). The Pennsylvania Railroad: Volume I, Building an Empire, 1846-1917. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4348-2. OCLC 759594295.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goode, James W. (2003). Capital Losses: A Cultural History of Washington's Destroyed Buildings (2 ed.). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books. ISBN 978-1-58834-105-1. OCLC 800333753.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moore, Charles (1921). Daniel H. Burnham: Architect, Planner of Cities. 1. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Union Station (Washington, D.C.). |

- Official website

- Washington Union Station – Amtrak

- Union Station Information - Virginia Railway Express

- Washington (WAS) – Great American Stations (Amtrak)

- Union Station, a brief history – National Railway Historical Society

- Station building from Google Maps Street View

- Union Station, a documentary produced by WETA-TV (2008)