Healy Hall

Healy Hall is a National Historic Landmark and the flagship building of the main campus of Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. Constructed between 1877–1879, the hall was designed by Paul J. Pelz and John L. Smithmeyer, prominent architects who also built the Library of Congress. The structure was named after Patrick Francis Healy, who was the President of Georgetown University at the time.

Healy Hall | |

U.S. National Historic Landmark District Contributing Property | |

| |

| |

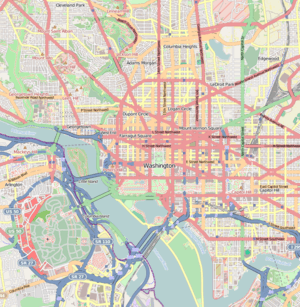

| Location | Georgetown University, Washington, D.C. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 38°54′26.2″N 77°04′21.8″W |

| Built | 1877–1879 |

| Architect | Smithmeyer and Pelz |

| Architectural style | Gothic Revival and Romanesque |

| Part of | Georgetown Historic District (ID67000025) |

| NRHP reference No. | 71001003 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | May 25, 1971 |

| Designated NHL | December 23, 1987[1] |

| Designated NHLDCP | May 28, 1967 |

| Designated DCIHS | November 8, 1964 |

Healy Hall serves as the main administrative and reception venue of Georgetown, with some portions still being used as classrooms. The building includes Riggs Library, one of the few extant cast iron libraries in the nation, as well as the elaborate Gaston Hall.

History

The building was built during the presidency of Patrick Francis Healy after whom it is named.

The construction of the building, from 1877 to 1879, dramatically increased the amount of classroom and living space—at the time, it was also used as a dormitory—of what was then a small liberal arts college. Prior to its construction, Old North housed most of the college's classrooms, dormitories, and other facilities.[2] The construction also left the university deeply in debt and in possession for years of an enormous pile of dirt as a result of the excavation, with no funds to remove it. As a result of the debts, the Gaston Hall auditorium could not be completed until 1909.

The building was listed on District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites in 1964,[3] on the National Register of Historic Places on May 25, 1971, and as a National Historic Landmark on December 23, 1987. In addition, it is a contributing property of the Georgetown Historic District, which was listed as a National Historic Landmark District on May 28, 1967.[4][5]

The building was brought to national attention in 1973 when it acted as a prominent background for the film The Exorcist. In 1990 the interior hall and also the second story of the building featured in The Exorcist III.

Architecture

_at_the_Healy_Hall%2C_Georgetown_University.jpg)

Built in a Neo-Medieval style that combines elements of Romanesque, Early Gothic, Late Gothic and Early Renaissance, the building contains the Office of the President; Georgetown's Department of Classics; the Kennedy Institute of Ethics; and the Bioethics Research Library.

Notable rooms in Healy include Riggs Library, one of the few extant cast iron libraries in the nation; the Philodemic Room, the meeting room for the Philodemic Society, one of the oldest collegiate debating clubs in the nation; the grand Hall of Cardinals; the historic Constitution Room; and the Carroll Parlor, which houses several notable pieces from the university's art collection.

Perhaps the grandest space in the building is Gaston Hall, Georgetown's "Jewel in the Crown",[7] the 750-seat auditorium which has played host to multitudes of world leaders. Gaston Hall, located on the third and fourth floors and named for Georgetown's first student, William Gaston, is decorated with the coats of arms of the Jesuit colleges and universities and rich allegorical scenes painted by notable Jesuit artist Brother Francis C. Schroen. Schroen also created the intricate paintings found in the Carroll Parlor and on the ceiling of the Bioethics Reference Center's Hirst Reading Room.

Healy Hall rises to a height of 200 feet (61 m), making it the tied with 700 Eleventh Street as the sixth tallest building in Washington, D.C.[8]

Clock hands

The hands of the Healy Clock Tower have been subjected to many thefts, as per the university tradition.[9] Historically, students would steal the hands and mail them to the person they wished to visit the campus, most notably sent to the Vatican, where they were blessed by Pope John Paul II and then returned to the university.[10][11] One such incident caused significant damage to the clock mechanism, however, and security has been increased as a result in recent years, decreasing the incidence of the theft.[12] These measures have not prevented students from successfully obtaining the hands however, as they are captured every five to six years, such as in the fall of 2005 by Drew Hamblen (SFS ’07) and Wyatt Gjullin (COL ’09).[13] The hands were stolen once again during the evening between April 29 and April 30, 2012, and supposedly sent to Barack Obama but the hands ended up lost in the mail.[14] More recently, the clock hands were stolen during the evening between December 9th and December 10th, 2014,[15] and again sometime during the night of April 30, 2017.[16]

Dean M. Carignan (SFS '91) has written of his stealing the clock hands during his freshman year. On April 1, 1988, Carignan and a fellow student accessed the clock through "a metal plate set into the roof at the base of the clocktower." Eventually tracked down by campus security, Carignan and his Georgetown accomplice were sentenced by a university discipline panel to "an $800 fine, a 40-hour work sanction, [and] a year of probation."[17]

The writer Joseph Bottum has also published an account of stealing the clock hands. In the Fall of 1977, Bottum joined Stan DeTurris, Dave Barry, and Pat Conway (all freshmen in the class of ’81) to climb through a trap door on the north peak of Healy, above Gaston Hall, and steal the hands from the east face of the clock, returning them at the end of the school year to the university president, Fr. Timothy Healy, S.J. The next year, Bottum writes, he and DeTurris found another way into the attics of Healy Hall, crawling through the ducts above Riggs Library to steal the minute hands from both the east and west clock faces.[18]

Image gallery

South side of Healy Hall

South side of Healy Hall Healy at Sunset

Healy at Sunset- Healy from the main entrance

- Gaston Hall

Healy among other spires

Healy among other spires The Philodemic Society Room in 1910

The Philodemic Society Room in 1910 Healy Hall in 1904

Healy Hall in 1904- Riggs Library in 1969

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Healy Hall. |

- Listing Archived 2011-06-06 at the Wayback Machine at the National Park Service

- Toporoff, Andrew (February 8, 2012). "Listening to Architecture: What Georgetown University Says Today". The Hoya. Archived from the original on October 12, 2016. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- "District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites: Alphabetical Version" (PDF). planning.dc.gov. Government of the District of Columbia. 30 September 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- "Asset Detail: Georgetown Historic District". National Park Service. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- "Georgetown Historic District" (PDF). planning.dc.gov. Government of the District of Columbia. February 13, 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 February 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Andrew Wallender Carroll Parlor Opens for Senior Study, The Hoya, 31 March 2015

- "Georgetown's Jewel in the Crown". georgetown.edu. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- Weeks, Christopher (1994). AIA Guide to the Architecture of Washington (Third ed.). Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 223–4.

- Heberle, Robert (2005-09-27). "Healy Clock Hands Stolen Over Weekend". The Hoya. Archived from the original on 2007-08-12. Retrieved 2007-03-28.

- Heberle, Robert (2005-10-07). "Pilfering A GU Landmark". The Hoya. Archived from the original on 2007-08-12. Retrieved 2007-03-28.

- Sheridan, Patrick (2006-01-31). "Healy Duo Receives One Year Probation". The Hoya. Retrieved 2007-03-28.

- Balz, Chrissy A. (2005-11-08). "Healy Clock Theft Has Roots in GU History". The Hoya. Archived from the original on 2008-12-05. Retrieved 2007-03-28.

- Heberle, Robert (2005-10-14). "Students Confess In Clock Case". The Hoya. Archived from the original on 2012-03-28. Retrieved 2007-03-28.

- Hinchliffe, Emma (2012-05-17). "Clock Hands Tradition Rekindled". The Hoya. Archived from the original on 2014-11-14. Retrieved 2014-06-25.

- "GUPD confirms the Healy clock hands were stolen". georgetownvoice.com. 10 December 2014. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- Cirillo, Jeff (2017-05-01). "Suspects Identified in Healy Tower Clock Hands Theft". The Hoya. Archived from the original on 2017-05-08. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- Carignan, Dean M. (1992-02-01). "The Idler: Tempus Fugit". Crisis magazine. Archived from the original on 2017-04-01. Retrieved 2017-03-31.

- Bottum, Joseph (2017-04-10). "Time Bandits". Weekly Standard. Archived from the original on 2017-03-31. Retrieved 2017-03-31.