Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park

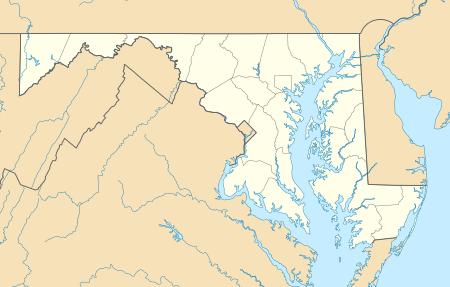

The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park is located in the District of Columbia and the state of Maryland. The park was established in 1961 as a National Monument by President Dwight D. Eisenhower to preserve the neglected remains of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal and many of its original structures. The canal and towpath trail extends along the Potomac River from Georgetown, Washington, D.C., to Cumberland, Maryland, a distance of 184.5 miles (296.9 km). In 2013, the path was designated as the first section of U.S. Bicycle Route 50.[2][3]

| Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park | |

|---|---|

IUCN category V (protected landscape/seascape) | |

| |

| |

| Location | extending from Cumberland, MD to Georgetown, Washington, DC, United States |

| Nearest city | Washington, D.C. |

| Coordinates | 38°53′59″N 77°03′28″W |

| Area | 19,586 acres (79.26 km2) |

| Established | September 23, 1938 |

| Visitors | 3,937,504 (in 2011)[1] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park |

The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal

Construction on the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal (also known as "the Grand Old Ditch" or the "C&O Canal") began in 1828 and ended in 1850 when the canal reached Cumberland,[4]:1 far short of its intended destination of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Occasionally there was talk of extending the 184.5-mile canal: for example, an 1874 proposal to dig an 8.4-mile tunnel through the Allegheny Mountains,[5] and there was a tunnel built to connect with the Pennsylvania canal.[6] Even though the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) beat the canal to Cumberland by eight years, the canal was not entirely obsolete. Only in the mid-1870s did larger locomotives and the adoption of air brakes allow the railroad to set rates lower than the canal, sealing its fate.[7]

The C&O Canal operated from 1831 to 1924 and served primarily to transport coal from the Allegheny Mountains to Washington D.C.[8]:6 The canal was closed in 1924, in part due to several severe floods that devastated the canal's financial condition.[9]

Federal Government purchases Canal

In 1938, the abandoned canal was obtained from the B&O Railroad by the United States in exchange for a loan from the federal Reconstruction Finance Corporation.[10] The government planned to restore it as a recreation area. Additionally, it was viewed as a project for employment for the jobless during the Great Depression. By 1940, the first 22 miles (35 km) of the canal were repaired and rewatered, from Georgetown to Violettes lock and returned to operating condition by African-American enrollees with the Civilian Conservation Corps.[11] The first Canal Clipper boat, giving mule driven rides, began in 1941.[12] It was later replaced by the John Quincy Adams in the 1960s.

The project was halted when the United States entered World War II and resources were needed elsewhere. In 1941, Harry Athey suggested to President Franklin Roosevelt that the canal could be converted into an underground highway or a bomb shelter with its roof for landing airplanes. The whole idea was deemed impractical due to the river's periodic flooding.[13] In 1942, freshets destroyed the rewatered sections of the canal. National Park Service (NPS) official Arthur E. Demaray pressed that the canal from Dam #1 be restored, to supply water to the Dalecarlia Reservoir in case sabotage or bombing destroyed the normal conduits of water. Since this transformed the canal into a concern of national security, in 1942, the War Production Board approved the work.[14] By 1943, Congress had funded the work, repairs were done, and the Park Service resumed boat trips in October 1943.[15]

The Congress expressed interest in developing the canal and towpath as a parkway. Because of the flooding from the 1920s to the 1940s, the Army Corps of Engineers proposed building 14 dams, that would have permanently inundated 74 miles of towpath, as well as the Monocacy and Antietam aqueducts.[16] Around 1945, the Corps wanted to remove Dam #8, which would destroy any hope of rewatering the canal above Dam #5, as well as put a levee around in the Cumberland area. Much of this was done, with the NPS cooperating with the Corps, since maintaining an operating canal all the way to Cumberland was too expensive, as well as wanting to preserve the western parts of the canal.[17]

Creation of the national park

.jpg)

The Douglas Hike

The idea of turning the canal over to automobiles was opposed by some, including United States Supreme Court Associate Justice William O. Douglas. In March 1954, Douglas led an eight-day hike of the towpath from Cumberland to D.C.[10] Although 58 people participated in one part of the hike or another, only nine men, including Douglas and Olaus Murie, hiked the full 184.5 miles (297 km). Following this hike, Justice Douglas formed a committee, later to be known as the C&O Canal Association in 1957, which would draft plans to preserve and protect the Canal.[18] Serving as the chairman of this group, his commitment to the park proved successful.

Towpath

In 1958, the entire path was cleared for hiking and a 12-mile bicycle trail was built on the towpath, from Georgetown's Mule Bridge at 34th Street in Washington, DC to Widewater, MD.[19] The bicycle trail was built by laying crushed blue stone over the muddy towpath and opened on November 22, 1958.[20] Cyclists were biking the full route by 1960.[21]

National monument, then national park

In 1961, President Dwight Eisenhower made the canal a national monument under the Antiquities Act, but that hardened the opposition to making the canal a national park. There was some support for making the Potomac River a national river instead.[22] Within ten years, the political climate had changed, and realizing that the national river plan was unsupportable, the idea of turning the canal into a historic park had little opposition. The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park Act [23] established the canal as a National Historical Park and President Richard Nixon signed it into law on January 8, 1971.[22][24]

Floods of 1996

The winter and summer of 1996 saw two separate floods. Following a blizzard in January, heavy rains washed away the snow and caused extreme flooding and run-off. This major winter flood swept across 80 to 90 percent of the canal and towpath, causing high waters, along with the adjacent Potomac River. Erosion due to the floods lead to heavy damages to the towpath and much of the infrastructure of the canal and park. Following the winter flood, there was an overwhelming need for volunteers in response to the damages caused. Unfortunately, in September, Hurricane Fran caused even more damage to the canal in multiple parts, requiring workers and volunteers to restore and reconstruct the towpath and re-water the canal, several major projects that would take a large amount of time and money to complete.[25]

Restoration efforts

Today, several organizations work to preserve and restore the park's beauty and history. The C&O Canal Trust,[26] founded in 2007, is the official non-profit partner of the National Park Service. The C&O Canal Association [27] is an all-volunteer citizens organization established in 1954 to help conserve of the natural and historical environment of the C&O Canal and the Potomac River Basin. Together they are making progress in restoration efforts of Canal infrastructure, fixing eroded sections of the towpath and re-watering sections of the Canal to keep it beautiful for both visitors and wildlife, as well as educating the community on the Canal's rich history in interactive ways at the six different visitor centers along the canal: Georgetown, Great Falls Tavern, Brunswick, Williamsport, Hancock, and Cumberland, operated by the National Park Service and its rangers.[28]

Current restoration and construction efforts include restoring and rewatering the Conococheague Aqueduct,[29] restoring Locks 3 and 4,[30] repairs at Great Falls (Lock 20) and Swain's Lock (Lock 21).[31] A second phase of work at the Paw Paw tunnel started on May 13, 2019.[32]

Today

Extent

The park includes nearly 20,000 acres (80 km2) in a strip along the Potomac River. A small portion of the towpath near Harpers Ferry National Historical Park doubles as a section of the Appalachian Trail.

The canal begins at its zero mile marker (accessible only via Thompson's Boat House), directly on the Potomac, opposite the Watergate complex. Author John Kelly, writing for the Washington Post in 2004, suggested that the name of the Watergate complex may derive from its location directly adjacent to the canal's zero milepost, where to this day, the canal's large wooden gate sits directly on the Potomac and adjacent to the complex.[33] Kelly wrote, a canal lock is "quite literally, a water gate." [33][34]

In Allegany County, Maryland, the park includes the Western Maryland Railroad Right-of-Way, Milepost 126 to Milepost 160, listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1981.[35][36]

Flooding continues to threaten historical structures on the canal and attempts at restoration. The Park Service has re-watered portions of the canal, but the majority of the canal does not have water in it.

Usage

Varied in its geography, the canal and its towpath along with the adjacent Potomac offers activities including running, hiking, biking, fishing, boating and kayaking, as well as rock climbing in certain locations. The Canal also offers a variety of wildlife and birdwatching opportunities.

The seven National Park Service visitor centers have displays and interpretive exhibits on the history of the canal.[37] The park offers rides on two reproduction canal boats — the Georgetown and the Charles F. Mercer (named after the first president of the Canal corporation, and not the first boat on the canal named Charles F. Mercer) — during the spring, summer and autumn. The boats are pulled by mules, and park rangers in historical dress work the locks and boat while presenting a historical program.

Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park receives around five million recreation visits annually.[38] Access through the Great Falls Tavern Visitor Center requires payment, but access anywhere else in the park is free.[37] In January 2015, the National Park Service proposed adding entrance fees to virtually all access points along the towpath; the proposal was rescinded in February, amid backlash from communities along the canal.[39]

Hiker biker campsites

The National Park Service maintains a number of hiker/biker campsites, about every 5–7 miles (8–11 km) along the towpath.[40] These are available for free on a first come first served basis. Each site has a water pump (mid-April to mid-November), picnic area, firepit, and latrine;[40] nearest vehicular access points vary from 0.2 miles (0.3 km) to "remote".[41] Here is a list of the hiker biker campsites (data from NPS):[40]

Other camping

The C&O Canal NHP also offers tent and primitive RV campsites for individuals and group as large as 35.[42] Not all campsites have all amenities; campsites may have some or all of parking, restrooms, picnic tables, boat ramp, and nearby shopping.[42] Hiker-biker campsites are free of charge to use for a maximum of one night per trip.[42] They are used under a first-come, first-served basis. As of December 1, 2016 all drive-in (car) campsites moved from a first-come, first served system to a reservation system on Recreation.gov.[43] Group campsites are $40 during peak season and $20 during off season. Here is a list of the drive-in, reservation campsites: (data from NPS):[40]

| Towpath Mileage | Campsite | Type | Fee per Night | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11.0 | Marsden Tract | Group | $40/20 | Permit required |

| 69.9 | Antietam Creek | Car | $20 | |

| 110.4 | McCoys Ferry | Car, Group | $20 | |

| 140.9 | Fifteenmile Creek | Car, Group | $20 | |

| 156.1 | Paw Paw Tunnel | Car, Group | $20 | |

| 173.3 | Spring Gap | Car, Group | $20 | |

Gallery

Going 184.5 miles (296.9 km) upstream from Georgetown to Cumberland, Maryland.

Mile marker 0 (behind Thompson's Boat House) at the start of the canal, where it meets the Potomac River. Note the remains of the waste weir in the background.

Mile marker 0 (behind Thompson's Boat House) at the start of the canal, where it meets the Potomac River. Note the remains of the waste weir in the background. The Rock Creek Basin, just before the Tidewater Lock

The Rock Creek Basin, just before the Tidewater Lock Remains for a Mill Water Intake on the 4 mile level (Georgetown) just below Key Bridge. The canal sold water to several mills.

Remains for a Mill Water Intake on the 4 mile level (Georgetown) just below Key Bridge. The canal sold water to several mills. Remains of stop gate at 2.18 miles on 4 mile level. Only visible when canal is drained

Remains of stop gate at 2.18 miles on 4 mile level. Only visible when canal is drained The NPS built this spillway (also on the 4 mile level) in 1936.[44] Note the Chain Bridge in background

The NPS built this spillway (also on the 4 mile level) in 1936.[44] Note the Chain Bridge in background Historic mile marker 4, just after second spillway

Historic mile marker 4, just after second spillway Hydroelectric plant on 4 mile level of Georgetown

Hydroelectric plant on 4 mile level of Georgetown George Washington's Patowmack Canal, used as a feeder, goes to the left, the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal goes to the right.

George Washington's Patowmack Canal, used as a feeder, goes to the left, the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal goes to the right. Lock 6. Groundbreaking was near this spot

Lock 6. Groundbreaking was near this spot Historic mile marker 9, by Lock 11 (Seven Locks area).

Historic mile marker 9, by Lock 11 (Seven Locks area). This spot here was called the "Log Wall": builders put a log wall here, filled with rubble, to make the canal. Hurricane Agnes washed it out completely in 1972, and the NPS erected this retaining wall without logs.

This spot here was called the "Log Wall": builders put a log wall here, filled with rubble, to make the canal. Hurricane Agnes washed it out completely in 1972, and the NPS erected this retaining wall without logs. Kayak lessons at Widewater (near Anglers Inn, below Lock 15).

Kayak lessons at Widewater (near Anglers Inn, below Lock 15). Widewater in winter

Widewater in winter Lock 15 at the end of Widewater

Lock 15 at the end of Widewater Cliff face at the Billy Goat Trail in Maryland

Cliff face at the Billy Goat Trail in Maryland Great Falls Tavern on the C&O canal in Potomac, Maryland

Great Falls Tavern on the C&O canal in Potomac, Maryland Canal Clipper boat (since retired) at Lock 20

Canal Clipper boat (since retired) at Lock 20 Snubbing Charles F. Mercer at Lock 20.

Snubbing Charles F. Mercer at Lock 20. Canal at Swain's Lock (Lock 21)

Canal at Swain's Lock (Lock 21) Mile marker 17, with stump of broken historic mile marker on left

Mile marker 17, with stump of broken historic mile marker on left Mile marker 22, just before Violette's Lock and the Seneca Feeder

Mile marker 22, just before Violette's Lock and the Seneca Feeder Horsepen Branch Hiker/Biker campsite.

Horsepen Branch Hiker/Biker campsite. Chisel Branch Hiker/Biker campsite sign.

Chisel Branch Hiker/Biker campsite sign. Turtle Run Hiker/Biker campsite, below White's Ferry

Turtle Run Hiker/Biker campsite, below White's Ferry Canal prism by White's Ferry. Note ruins of abandoned grainery on left.

Canal prism by White's Ferry. Note ruins of abandoned grainery on left. A typical hiker/biker campsite along the Canal. This one is the Marble Quarry Campsite, near mile 38, below Lock 26.

A typical hiker/biker campsite along the Canal. This one is the Marble Quarry Campsite, near mile 38, below Lock 26. Ruins of an abandoned granary, below the Monocacy Aqueduct

Ruins of an abandoned granary, below the Monocacy Aqueduct Indian Flats Hiker/Biker campsite, just above the Monocacy Aqueduct

Indian Flats Hiker/Biker campsite, just above the Monocacy Aqueduct Lock 28 near Point of Rocks, Maryland

Lock 28 near Point of Rocks, Maryland Lock 33 near Harpers Ferry, West Virginia

Lock 33 near Harpers Ferry, West Virginia The Patowmack Canal's House Falls canal here was reused for the C&O.

The Patowmack Canal's House Falls canal here was reused for the C&O. Mowing the grass along the canal, near Guard Lock 3

Mowing the grass along the canal, near Guard Lock 3 Big Slackwater. Here the boats navigated in the slackwater behind Dam 4, hence there is only a towpath. It was repaired and reopened in 2012.

Big Slackwater. Here the boats navigated in the slackwater behind Dam 4, hence there is only a towpath. It was repaired and reopened in 2012. McMahon's mill, along Big Slackwater

McMahon's mill, along Big Slackwater More Big Slackwater, above McMahon's Mill.

More Big Slackwater, above McMahon's Mill. Lift bridge (abandoned) for Railroad crossing canal.

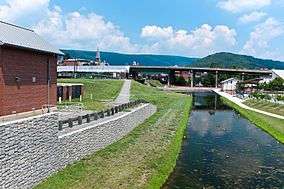

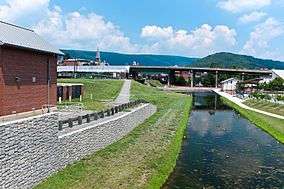

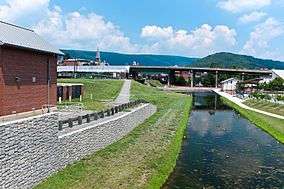

Lift bridge (abandoned) for Railroad crossing canal. Cushwa Basin and Visitor Center at Williamsport, Maryland

Cushwa Basin and Visitor Center at Williamsport, Maryland

Dam 5, which makes Little Slackwater.

Dam 5, which makes Little Slackwater. Little Slackwater, above Dam 5. This is one of the most dangerous areas for cyclists, with only a narrow towpath, no guardrail, and a long drop to the river below.

Little Slackwater, above Dam 5. This is one of the most dangerous areas for cyclists, with only a narrow towpath, no guardrail, and a long drop to the river below. Lock 49 at Four Locks.

Lock 49 at Four Locks. Lockkeeper's shanty, to look out for boats. Lock 50, with Locks 49 and 48 in the background. This is at the Four Locks area.

Lockkeeper's shanty, to look out for boats. Lock 50, with Locks 49 and 48 in the background. This is at the Four Locks area. Big Pool on the 14 mile level.

Big Pool on the 14 mile level. Park Service maintenance area for the Allegheny Division/Four Locks Subdivision of the Canal

Park Service maintenance area for the Allegheny Division/Four Locks Subdivision of the Canal

The canal at Hancock, Maryland

The canal at Hancock, Maryland

Division superintendent's house, about half a mile (0.8 km) above Paw Paw Tunnel

Division superintendent's house, about half a mile (0.8 km) above Paw Paw Tunnel Maryland Route 51 crosses the canal about 0.6 miles (0.97 km) above the tunnel, on the 8 mile level.

Maryland Route 51 crosses the canal about 0.6 miles (0.97 km) above the tunnel, on the 8 mile level.

Lock 69 pool at Oldtown, Maryland

Lock 69 pool at Oldtown, Maryland Lock 70 at Oldtown, Maryland

Lock 70 at Oldtown, Maryland Looking downstream at Spring Gap; canal towpath and prism to the left, and Spring Gap campground to the right.

Looking downstream at Spring Gap; canal towpath and prism to the left, and Spring Gap campground to the right. Dilapidated canal prism at Spring Gap (to the left of the previous photo)

Dilapidated canal prism at Spring Gap (to the left of the previous photo) Lock 74, with Lock 73 in background.

Lock 74, with Lock 73 in background. Lock 75, the last lock on the Canal before Cumberland.

Lock 75, the last lock on the Canal before Cumberland.

Canal just above Lock 75 on 9 mile level at mile marker 176.

Canal just above Lock 75 on 9 mile level at mile marker 176. One of the various culverts (No. 239) on the 9 mile level.

One of the various culverts (No. 239) on the 9 mile level. Canal around mile marker 184, looking downstream. Potomac River is on the right side.

Canal around mile marker 184, looking downstream. Potomac River is on the right side. Evitts Creek Aqueduct, the final aqueduct on the C&O Canal.

Evitts Creek Aqueduct, the final aqueduct on the C&O Canal.

Looking at the end of the canal. Guard Lock 8 is on the left side at the end. Highway bridge in background is I-68.

Looking at the end of the canal. Guard Lock 8 is on the left side at the end. Highway bridge in background is I-68. Looking at Guard Lock 8 today. Red brick building behind highway is the Canal Place museum and the Western Maryland Railroad Station.

Looking at Guard Lock 8 today. Red brick building behind highway is the Canal Place museum and the Western Maryland Railroad Station. Guard Lock 8, which was actually two locks. Downstream lock is filled in. Upstream lock has a water pump to supply water to the basin.

Guard Lock 8, which was actually two locks. Downstream lock is filled in. Upstream lock has a water pump to supply water to the basin. Mile marker 184.5 at end of canal, with Guard Lock 8 in the background.

Mile marker 184.5 at end of canal, with Guard Lock 8 in the background.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park. |

See also

- Bear Island

- Billy Goat Trail

- Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Association

- Great Falls of the Potomac River

- Olmsted Island

References

- "National Park Service Visitor Use Statistics". National Park Service. Retrieved October 5, 2012.

- Vitale, Marty (October 28, 2013). "Meeting Minutes for October 17, 2013, and Report to SCOH October 18, 2013 (Addendum October 28, 2013)" (PDF). Denver, Colorado: Special Committee on U.S. Route Numbering, American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-05. Retrieved June 9, 2014.

- "New U.S. Bicycle Routes Approved in Maryland and Tennessee". adventurecycling.org. Missoula, Montana: Adventure Cycling Association. 2013-11-05. Retrieved 2013-11-05.

- Mackintosh, Barry (1991). C&O Canal: The Making of A Park. Washington, DC: National Park Service, Department of the Interior.

- Hahn, Pathway. 257

- Davies, William E. (1999). The Geology and Engineering Structures of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal: An Engineering Geologist's Descriptions and Drawings (PDF). Glen Echo, Md.: C&O Canal Association. Retrieved 2014-07-21. p. ix. Davies does not indicate if this tunnel was ever used, nor its location.

- Davies, p. ix

- Hahn, Thomas (1984). The Chesapeake & Ohio Canal: Pathway to the Nation's Capital. Metuchen, New Jersey: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-1732-2.

- National Park Service. "Canal Operations". Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historic Park. Nps.gov. Retrieved 2010-05-11.

- Lynch, John A. "Justice Douglas, the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal, and Maryland Legal History". University of Baltimore Law Forum. 35 (Spring 2005): 104–125.

- Shaffer p. 71

- "CHAPTER TEN: USING THE PARK". Archived from the original on 2013-06-21.

- Shaffer, p. 70

- Shaffer p. 73

- Shaffer p. 76

- Shaffer p. 78

- Shaffer p. 79

- "Associate Justice William O.Douglas". National Park Service. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- "Canal's Path Cleared for Full Length". The Washington Post. 6 September 1958.

- Carper, Elsie (23 November 1958). "Group of 40 Cyclists Pioneers New 12-Mi. C&O Canal Path". The Washington Post.

- Jordan, Jane (20 March 1960). "Bike Club to Take 180-Mile Spin". The Washington Post.

- "The Battle to Save the Canal, Part V (from December 2011 Along The Towpath)" (PDF). Candocanal.org. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park Act, Pub.L. 91–664, January 8, 1971.

- "16 USC Chapter 1, Subchapter LVI: Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park". Office of Law Revision Council. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- "Teams Assess C&O Canal Damage On the Potomac: Last Weekend's Floods Washed out Sections of the Historic Park's Towpath and Walkways. Many Areas Will Be Closed Indefinitely". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- "The C&O Canal Trust: About Us". C&O Canal Trust. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- "About the C&O Canal Association". C&O Canal Association. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- "Plan Your Visit". NPS. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- https://www.nps.gov/choh/planyourvisit/conococheague-groundbreaking.htm

- "Construction Updates - Georgetown - Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov.

- "Repair Watered Structures Project - Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- "Paw Paw Tunnel Scaling Project - Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- Kelly, John (December 13, 2004). "Answer Man: A Gate to Summers Past". The Washington Post. p. C11.

- Moeller, Gerard Martin and Weeks, Christopher. AIA Guide to the Architecture of Washington, D.C. 4th ed. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-8018-8468-3

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- "Maryland Historical Trust". National Register of Historic Places: Western Maryland Railroad Right-of-Way, Milepost 126 to Milepost 160. Maryland Historical Trust. 2008-10-05.

- "Basic Information". Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park - DC, MD, WV. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved November 29, 2016.

- "Chesapeake & Ohio Canal NHP: Annual Park Recreation Visitation (1904 - Last Calendar Year)". NPS Stats: National Park Service Visitor Use Statistics. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved November 29, 2016.

- "Park service rescinds C&O Canal entrance fee proposal". The Journal. Hagerstown, Maryland. Associated Press. February 6, 2015. Archived from the original on February 11, 2015. Retrieved February 11, 2015.

- Park Planner: Chesapeake and Ohio Canal (PDF), National Park Service, Department of the Interior, 2014-11-27

- "Camping". C&O Canal Bicycling Guide. Bike Washington. Archived from the original on November 30, 2016. Retrieved November 29, 2016.

- "Camping - Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov.

- "Recreation.gov recreation area details - Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park - Recreation.gov". www.recreation.gov.

- Hahn, Thomas F. Swiftwater (1993). Towpath Guide to the C&O Canal: Georgetown Tidelock to Cumberland, Revised Combined Edition. Shepherdstown, WV: American Canal and Transportation Center. ISBN 0-933788-66-5. p. 24

- Butcher, Russell D. (1997). Exploring Our National Historic Parks and Sites. Roberts Rinehart Publishers

- National Park Service. Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park. Retrieved 2010-05-11.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park. |

- Chesapeake & Ohio Canal NHP - Official site

- CanalBird.com - "About The Chesapeake & Ohio Canal"

- C&O Canal is part of the Chesapeake Bay Gateways and Watertrails Network

- The Building of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal - A National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan