Internet access

Internet access has become a basic need for many leisure travelers. You may be glad to be free of it for a while, but keeping in contact with family and friends can be cumbersome without it. It is essential for most business travellers and for digital nomads who work while travelling. It may also be useful to access Wikivoyage and other travel-related sites wherever you are in the world.

Understand

Travellers have a wide variety of expectations and expertise regarding the Internet. Some will carry a device with them, such as a laptop or a smartphone, and they are just looking for a means to connect it. Some need to be online as much as possible, whereas others may be happy to check their email every week or so.

This article gives an overview of what options there are for travellers to connect to the Internet while travelling.

Access types

Wi-Fi

.jpg)

Virtually all laptops and PDAs manufactured since the mid-2000s, as well as most smart phones launched in the late 2000s, have Wi-Fi (WLAN) provisions. The downside of Wi-Fi is that even if it is wireless in nature, the coverage of a Wi-Fi access point or hotspot is limited compared to that of mobile Internet. Once you leave the building, you mostly lose the Wi-Fi signal provided to you.

Availability of Wi-Fi, especially free Wi-Fi, varies very much by region. In cities in developed countries there are usually lots of Wi-Fi access points, but finding free access points open to the public may require quite some searching. Local laws can hamper accessibility. In Germany a law that was worded in such a way that it could mean the owner of a WiFi connection was liable for any illegal acts done with it and only when this law changed did free open WiFi become common. In Turkey the government places heavy restrictions on the internet (including blocking Wikipedia but not Wikivoyage) and as such WiFi usually requires the user to be identified in some way.

Wi-Fi wireless access come in different types:

- Free and open public access points permit any device to access the Internet via Wi-Fi. These are sometimes provided by hotels, airports, restaurants, malls, libraries, or transportation networks. They are even sometimes available across entire city centres, such as Bristol, Cadiz, and Marseille. Often these require you to start up a browser to accept some terms and conditions before you can access the Internet. They may impose limits on the amount of time for which you can connect or the amount you can download in a day. They may limit access to browsing and email. They may require registration. Ironically, budget accommodations, including many hostels, are more likely to provide this service to guests at no additional charge than their 4- or 5-star luxury counterparts – which may charge ludicrous fees.

- Free but secured public access points work in the same way as free and open-access points, but will require a password (like a WEP or WPA-PSK key) to connect to the network. The passwords are in place to discourage non-patrons of the establishment from using it. These are more likely to be found in restaurants, budget accommodation and guest harbours. Openwifispots is a site where you can search for free Wi-Fi hotspots in cities all over the world.

- Private open access points left open by their owners, usually as a friendly gesture to the community. Using an inadvertently open connection is illegal in many countries, but more often legality problems arise from the Internet service provider forbidding sharing in its usage terms – which makes leaving it "inadvertently" open by purpose a serious option.

- Commercial public-access points. They usually charge per hour or day. Fees can be cheap, reasonable or very high, and can vary widely even within the same locale – even occurring alongside completely free service. A provider may provide free and fee-based Wi-Fi access at the same access point at the same time, with the fee-based access being faster. Such commercial access points are growing increasingly common, especially in areas where travellers are 'trapped' (airports for example). Payment can be by credit card at the time of use, or by prepaid card/voucher, or through an arrangement with your mobile/cell phone carrier.

- Community-access points. You become a member of a Wi-Fi community (usually by donating your own access point) and use the community's access points for free.

- Roaming gives you guest access to private or commercial access points on the basis of some contract or relationship that you have with an institution or company at home. An example is Eduroam, a service that gives members of universities access to the wireless networks of other universities (and sometimes those of cooperating institutions around the city).

Public-access computers

The simplest form of access for the broadest range of users are computers made available to the public, usually for a fee or included as a service for patrons of a hotel, restaurant, or café. These are often available even in the most remote regions of the world, often driven by local demand for access to the Internet. In fact, they are often most common in areas where private, individual access to the Internet is least common. However, there can be difficulties:

- The only application you can generally count on being fully functional is a web browser, and sometimes some of their plug-ins are disabled. They may lack support to connect your camera, to use Skype, or to read IMAP/POP based email. You will want to make sure your email is accessible with a web interface.

- In many places, language is an issue. Even if you know your own computer well, using software in Arabic or Chinese will probably pose problems. Usually you can get a web browser to work, but not much else. It's worth being familiar with the keyboard layout of the country you are in (and your own), since the position of some punctuation keys differ, even if their writing system or language is the same as in your home country. You may be able to switch to a keyboard layout where you find the keys you need, but at the cost of not having the engravings on the keys match.

- Security is an issue, as café computers could potentially have keyloggers and other nasty forms of spyware to capture passwords, or temporary files may be left for other customers to find. See Security concerns below.

Cellular phones

- See also: mobile telephones

For GSM phones, the worldwide standard pretty much everywhere except Japan and South Korea, GPRS (packet data) is common. The newer UMTS standard and its enhancements HSDPA and HSPA+ are also widely available. Yet another, even faster standard named LTE has become widespread since 2013. While GPRS offers basic modem speeds suitable for email and some browsing (particularly text-heavy rather than graphics-heavy sites), the newer technologies offer speeds comparable to fixed-line broadband. Most modern GSM phones, even very cheap models, are GPRS enabled, and current smartphones are at least HSDPA enabled. Using mobile internet services may require activation with the provider.

Additionally, most smartphones can use wireless Internet (Wi-Fi, see above) even if they are not subscribed to any mobile telephone provider. As long as a Wi-Fi access point is in range, this can be used to make very inexpensive telephone calls using voice-over-IP applications and an unbundled VoIP provider.

Smartphones and their apps may generate quite a lot of Internet traffic on their own, such as by checking status or downloading updates, or the web browser downloading content never actually shown. Thus, if you enable Internet access, you are not going to pay only for your conscious Internet use. It may be worth checking how to minimize the "extra" Internet access. When using the phone as modem, this applies also to programs on your laptop.

There are two basic ways of using Internet with your phone:

- Use mobile Internet to download mail directly to your phone and surf the web. While this can be done on most any modern phone, you will want an iPhone/Android/Windows Phone-type device with a large screen to make this practical.

- Use mobile Internet to connect another device, typically a laptop, to the Internet. This is normally done with a USB link ("tethering") or a Wi-Fi link ("hotspot"). Be sure to shut down any PC apps which download pointless and costly "updates" in the background; what's tolerable on a fixed broadband connection quickly gets annoying on a dime-a-megabyte local prepaid SIM or a roaming handset.

Using Internet with the phone itself will come in handy if you have a smart phone with apps that help you navigate around the city or check social messaging sites.

Note that international mobile Internet roaming can be ludicrously expensive, so check with your operator at home before you start downloading those multi-megabyte attachments (or enable roaming data connections at all). In EU there are maximum prices, as long as you use an EU based SIM card and network (be careful in border regions and at sea).

The frequencies in use in the Americas, in general, do not match those in the other ITU zones. 850/1900 MHz are common in the Americas, while 900MHz along with 1800 or 2100 are common elsewhere. Unless your handset has the local frequencies, it will not work even if unlocked.

In the USA, CDMA (the system used by Verizon and Sprint) is widespread, and arguably the most available service outside of metropolitan areas. AT&T and fourth-ranked T-Mobile use GSM; there is also a confusing array of regional carriers and mobile virtual network operators (branded resellers). The incumbent Canadian telephone companies have shut down their CDMA in favour of HSDPA. CDMA phones can frequently be used as a computer modem with the purchase of an adapter cable, or increasingly they can provide Internet access to your laptop via their built-in Bluetooth, but they are slower than their 3G UMTS (W-CDMA, HSPA, HSDPA) successors. While not part of their basic cell phone service package, Verizon's "Quick 2 Connect" service provides 14.4 kbit/s Internet access at no additional charge to their customers using the phone and cable combination, and their BroadbandAccess and NationalAccess packages with additional laptop tethering add-on can be used to provide Internet access through many of their current phones.

Prepaid mobile Internet

Prepaid Internet plans on mobile devices are increasingly becoming more affordable and a local one may be far cheaper than roaming Internet access by your normal provider. With two providers you will have two SIM cards, which means you need to change back and forth to be reachable by your normal phone number, unless you have two devices or a dual SIM phone.

If you have a laptop, you can buy a mobile broadband modem ("connect card", "USB dongle" or similar; see Wireless modems below) for the 3G SIM and leave the phone alone. Some smart phones may also be able to use such an external device for Internet connections. Otherwise you might consider buying a cheap second phone to use for calls from people at home (or all calls). In that case you want to find out how to transfer contact information between the phones (maybe by storing it on the SIM card).

If your phone is locked to your carrier back home, there are plenty of mobile phone shops that can unlock it for you at a reasonable price (the warranty may become void though). Dongles you got with an Internet connection can probably be unlocked in a similar fashion.

For best results, purchase a prepaid 3G SIM card in the country you are visiting. The prepaid Internet plans come in the form of purchasing data bundles for a fixed price good for a certain number of days. An example of a plan is 200 MB for 3 days available for $4. You usually need to key-in something on your mobile phone (via the dialling keypad) or send an SMS. The cost is immediately deducted from your prepaid credits and service becomes active instantly. Check with the mobile provider if one day is equivalent to 24 hours or is good until midnight. If the latter, you might want to wait until after midnight before you activate it, or purchase the plan first thing in the morning. If the data plan incurs any recurring charges, be sure to cancel it when you're done.

Most plans that feature more than 30 MB for at least one day is more than enough for mobile Internet surfing, just make sure you go easy on the graphics. If you however wish to use a mobile tablet computer like an iPad, you may want to go with a heavier data plan. A few specific models (mostly late-model Apple gadgets) require a micro-SIM or nano-SIM card (as opposed to the normally used "mini" size). This is the same card, but with the plastic frame slightly reduced in size.

Once a plan is purchased, the only thing you will have to worry about is to ensure your device has sufficient battery life. Some smart phones can run out of battery very quickly especially if 3G functionality is on. Finding a place to charge your mobile device can be very difficult outside your hotel and most restaurants/snack shops are not very open to the idea of patrons charging their device. Coffee shops like Starbucks are an exception and won't mind as long as you buy some food or a beverage from them. If free Wi-Fi is available and your device is capable of Wi-Fi, you can save battery by switching-off the 3G capabilities of your phone and turning-on Wi-Fi.

Public-access phones and tablets

Many shops that sell smartphones and tablets now have a selection of these devices available to the public to try out. Often they are connected to the Internet, allowing you to do a quick web search or two absolutely free, without a device of your own. Just remember not to use any sensitive private information (user names, passwords, credit card numbers).

Wired Ethernet

Virtually all laptops manufactured in the past decade have provisions for wired Ethernet. USB Ethernet sticks can be purchased from computer stores. Pack an Ethernet cable.

Some hotel rooms and some other locations will provide standard RJ-45 Ethernet jacks which you can plug your computer into, although these are becoming less common due to widespread Wi-Fi deployment. Usually a local DHCP server will tell your computer its IP address and other connection details, so that the connection is set up automatically.

Internet cafés and libraries often do not allow this kind of access, instead offering public access computers or Wi-Fi (see above).

Ironically, high-class business hotels are more likely to charge for wired Internet and at really high rates (the abusive "incidental fees" often also extend to local telephone calls, an issue for the few remaining dial-up users, and countless other amenities included in the base price of a more reasonably-priced lodging). Choose at least a 24-hour or one-day rate as hotels charge less than two to three times the hourly rate (e.g. the hotel may offer Internet of $15 good for 1 hour but also $25 good for 24 hours, in this case choose the latter). Savings by buying access for several days at once are smaller, but may be cost-effective if you are going to use the connection every day.

Modems for land lines

A decade ago, most common laptop PC manufacturers used to include a primitive dial-up modem in their products. If you had brought your laptop with you, you may have been able to use the phone socket in a hotel room or a residential landline to connect to the Internet or to obtain facsimile service.

As modern laptops (from at least 2009 onward) no longer include the modem or a RS232 serial port, you will need an external modem (either a USB one, or with a USB to serial adapter). The modem often comes with a few plugs for different telephone jacks, if you do not have a suitable one, you need an adapter plug between the modem and the line.

You'll also need both a telephone line and an Internet service provider (or a computer set up to act as one).

While a dying breed, monthly local ISP dialup accounts are inexpensive (sometimes US$10 per month or less, not including the cost of the line or the local call). National or regional ISPs (such as Bell in Canada) often have long lists of local numbers in various cities. International voyagers could possibly set up a "global roaming" dialup account that has local access numbers in numerous countries. A national freephone or toll-free data number, if provided, will be more expensive as an Internet provider passes on its cost to you.

Pre-paid dialup is a good solution; if you are not providing ongoing billing details, there is no risk of ongoing charges. Some flat-rate ISPs may be no contract; you can cancel at any time but you need to remember to cancel!

Connections over voice-grade landlines are slow, comparable to GPRS, even slower on bad lines. Many applications (such as streaming video or real-time audio) are simply unusable. Check the cost; paying per minute, your "call" can be quite expensive as some countries routinely charge for local calls, overpriced hotels add ludicrous "incidental fees" and bills add up quickly in places where a long-distance or international call is required to access your ISP.

If a hotel's private branch exchange is built only to work with phones designed for the same system, it's incompatible with standard modems. It may even damage equipment if the seemingly-standard RJ-45 connector delivers a non-standard voltage. Other phones may be hard-wired, or the sockets inaccessible. If the telephone system relies on voice over Internet, even if it supports standard analog extensions, any virtual "telephone lines" it generates will be too unstable (jitter, dropouts) to work.

The number of places using dial-up Internet is dwindling. Anywhere on the beaten path there will be broadband; many rural areas too distant for ADSL or CATV coverage are deploying fixed wireless links for fear of being left behind economically. A few remote villages like Black Tickle, Labrador (population 130) were still using landline modems as late as 2015 as areas with no terrestrial broadband and no mobile signal. Further afield, many points are completely off the grid with no landlines. Chicken, Alaska gets broadband Internet via satellite, as do many remote Labrador wilderness hunting outfitters camps. The only telephone in the bush may be running as a virtual line over the same satellite Internet feed.

Wireless modems

Wireless modems are also becoming widely available. These modems are plugged to a desktop or laptop computer via a USB port and will receive a signal from a mobile phone provider, in the same way as if you were using your mobile phone as a modem. A program to connect to the Internet usually starts-up automatically after plugging. If not, printed instructions to install software are provided. These modems should use standard USB protocols, though, and thus be usable with the operating system support alone (but you may have to explicitly enable the connection).

Oftentimes modems are locked to a particular mobile provider and you must purchase the modem and a data SIM card (either prepaid or plan) as a bundle. SIM cards and top-up/recharge chards are usually available at convenience stores, from the provider's service centre or authorised dealer. Mobile broadband plans on a PC are generally affordable and can come as either time-bound or data-bound plans or both. For instance time-bound plans will last you for several hours or days while data-bound plans give you allowance of several hundred megabytes or a few gigabytes. Once your time is up or you have consumed the allowed data of your plan, the service is terminated or you may be charged at the "pay as you go rate" which is much more expensive than the bundled rates.

If you have a modem from before (and it is unlocked or you can unlock it), you can use an ordinary SIM card with a generous enough data plan. In places like Finland you can get prepaid limitless 3G/4G data access for a week for €8.

Accessing email

In many countries it is easier to use email to keep in touch with friends and family back home than it is to call home regularly. Email has advantages over phone calls: it doesn't require you to account for time zone differences before contacting your family, it doesn't cost any more to send e-mail around the world than down the street, and it's possible to contact many people with a single email. Just make sure that the recipients check their email regularly or let them know you will be sending them email from time to time.

Another advantage of email is that messages are easy to document. This comes in handy when you need a written record of accommodations or other arrangements as you can just print it out from a shop or save it on your smart phone.

Webmail provides access to your email over a web interface, and is necessary if you are going to be accessing email from a variety of locations and equipment. An increasing number of email providers such as ISPs are setting up webmail interfaces for their users so that they can check their mail on the road. But many people choose to use one of the dedicated webmail providers, many of whom provide a free service. You may want to set up a separate account also for security reasons, see below.

Some web access points will restrict access to sites known to host webmail. Examples include some research libraries, universities and private businesses who wish to discourage users from checking their personal email during work hours. However, almost all Internet cafés and other access points aimed at the public will allow you to access your webmail: for many of their users, webmail is the reason they are there.

Using dedicated email software like Outlook, Lotus Notes or Thunderbird or the Mac's Mail.app may be restricted if your ISP or the access point blocks access or requires access through a proxy server. Sometimes you can use them through VPN or reading email before trying to send any (thus providing your password).

Security concerns

- See also: Common scams#Connection scams

Network security

If you are using your own device, but connecting to a public wireless or wired network (any unfamiliar network) the provider of the network can eavesdrop on any unencrypted communication and read confidential data, or steer the connection to their own servers. However, many websites where this might be a concern — such as banks and corporate sites — make use of encryption to prevent eavesdropping and make it possible for you to notice connection hijacking. Use https for any sensitive web connections (look for the ending "s" in "https:" at the start of the address and the padlock icon in your web browser conveying to you that your connection is encrypted and the address of the site your connected to is certified as being the one it claims to be). The web browser does not know where you want to connect, however, so note the real address at home and look out for similar looking but different ones, such as banking.example.net instead of banking.example.com or any misspellings in the name (including similar letters in foreign scripts, which may look like being in an odd font). Take seriously any warnings your browser may give about insecure certificates – check at home to know what warnings are due to misconfiguration at the website, and what the real certificates should look like.

One way to avoid local eavesdropping and manipulation of the connection is to use a VPN service. A VPN encrypts your Internet connection and routes it through a 'tunnel' to the VPN provider. The rest of the connection is treated as where you physically near the VPN server. The downside is the encryption overhead and that also connections to local sites are routed overseas, via the server (unless configured otherwise). There are many VPN services available, both free and paid ones. Many universities and bigger employers provide the service for their students and staff.

Although eavesdropping or tampering of content should not be possible with encrypted connections (https, VPN etc.), they do not hinder an intruder from blocking the connection. If encrypted connections cannot be established and you resort to unencrypted ones instead, that may be exactly what the intruder wanted. Do not send sensitive data over such a connection.

Public computer security

If you are using a public computer, a common threat to a traveler's Internet security is key loggers and other programs designed to monitor the user's activity for information that can be exploited, such as online banking passwords, credit card numbers, and other information that could be used for identity theft. For this reason public Internet terminals (such as those found at libraries, hotels, and Internet cafés) should preferably not be used to make online purchases, or access banking information.

Avoid using important passwords on a public computer. Online banking on a public PC is particularly risky, and you should think twice before having your TANs or other security sensitive data be visible as not only can the computer be unsafe, but there have also been cases of security camera footage being used to spy PINs and TANs. Public libraries are a good source of public-access computers that should be generally trustworthy.

If you have to have access to potentially sensitive information on your journey, such as your professional email account, discuss with the security staff. Probably you have to carry a trusted device for the purpose. One-time passwords or a temporary account can help with some, but not all, of the problems.

If you're saving or downloading private files, transfer them directly to your memory stick/thumb-drive if possible and delete the files on the computer's hard drive after use; while some computers automatically do this, others don't. This does not save you from spyware, but avoids having the files accessible by later customers.

If a traveler must use their online banking or send credit card information using a public terminal the following precautions should be taken:

- Check for virus and spyware scanning software on the computer, and ensure it is enabled.

- Talk to your bank ahead of time, many banks can enable limits on your online banking profile that, for example, restrict the ability to transfer money to third parties who have not been pre-approved.

- Obtain a credit card with a provider that can issue you temporary, one-shot credit card numbers specifically for use in online purchases.

- Always be certain you have logged out of your online banking, and shutdown/restart the computer before walking away.

Circumventing censorship

Types of censorship

Content filters

Some Internet cafés and Internet providers may restrict access to certain websites based on content. Common restricted content includes: sexual content, content unsuitable for children, commercial competitors and political content of certain types. The blocks can be wide-ranging, blocking for example, any site that includes the word "breast". With some misfortune any site might be blocked by mistake. They may also block access to certain types of traffic, for example web (HTTP or HTTPS), e-mail (POP or IMAP), remote shell (SSH).

Political firewalls

Several countries (for example China) have a policy of blocking access to different areas of the Internet at a country level. The description below is based on China's access policy, but applies to several other countries (such as Cuba, Myanmar, Syria, South Korea, North Korea, Iran, Thailand, Singapore, ...).

Typically the following sites may be blocked: human-rights NGOs' sites; opposition sites; universities; news outlets (BBC, CNN, etc.); blogging or discussion forums; webmail; social media; search engines; and proxy servers. Often they will duplicate the sites that have been blocked but (not so) subtly modify the content. Websites, pages, or URLs containing certain banned keywords may also be blocked. The firewalls may block non-political content such as pornography, and may also block some foreign websites as a form of economic protectionism to help domestic competitors. Some sites may not be blocked completely but instead slowed down to the point of being virtually unusable.

IP geofiltering

An increasing number of services on the Internet are restricted to IP address ranges corresponding to a certain country. If you try to access those services from outside that country, you will be blocked. Examples include video-on-demand (Movielink, BBC iplayer, Channel 4), web radio (Pandora), and News. Content providers want to make sure their service is only available to residents within its legislation, usually to avoid possible copyright breaches in other countries. IP geofiltering is a simple, if somewhat crude way of achieving this. For travellers this can be very frustrating, since the system discriminates based on where your computer is located, not on who you are and where you live. So even if you have legitimately signed up for a movie rental service in the US, you can no longer use it while you are spending a week in the UK. Youtube also blocks a lot of its content based on the location of its users and there are a variety of plugins and apps to circumvent this. You should consider getting one of those before going to Germany specifically, as it is one of the countries with the most blocked Youtube content (where Youtube is legal, that is).

Fortunately there are straightforward ways of getting around IP-geofiltering. Your best option is to re-route your Internet traffic via an IP address in your country of origin. The service will then think that your computer is located there and allow access. One way of doing this is to sign up with a VPN provider. See below for details.

VoIP blocking

Certain Internet providers and hotels around the world have started the practice of blocking all VoIP traffic from their networks. Though they usually justify this with esoteric explanations such as "to preserve network integrity", the real reason is normally much simpler: VoIP allows travellers to make free or very cheap phone calls, and the authority/company in question wants to force the user to make expensive phone calls over its plain old telephone land line. In the worst case, VoIP traffic can be blocked in a whole country (this tends to happen in countries with a state telephone monopoly). Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are known for blocking VoIP services.

The best anti-VoIP-blocking measure currently available to an average traveller is a VPN provider (see below). Make sure that you choose a VPN provider with sufficient bandwidth, otherwise your phone calls may suffer from poor quality/disconnects/delay.

Signal jamming

Some venues attempt to interfere with mobile telephones and their associated data services by willfully transmitting interference on the same frequencies. A more subtle variant transmits fraudulent data packets; a handset can be tricked into connecting to a bogus base station instead of a real carrier's towers, or a client-owned mobile Wi-Fi hotspot may be disrupted by sending bogus "dissociate" packets to disconnect the user. By their nature, the interfering signals don't abruptly stop at the edge of the offending vendor's property but fade gradually into free space at a rate based on the square of the distance to the interference source. For this reason, jamming devices are illegal to operate (and often illegal to sell) in most industrialised Western nations, with rare exceptions granted for prisons or sensitive government installations. In 2014, the US Federal Communications Commission levied a $600,000 fine against the Marriott hotel chain for jamming client-owned mobile Wi-Fi hotspots on the convention floor of one of its hotels in Nashville.

If the Wi-Fi connection between a mobile handset and a portable computer is being subjected to unlawful interference, replacing the wireless link with a USB "tether" cable will mitigate the problem; the same is not true if the signal from the upstream cellular telephone network is being jammed. In developed nations, complaints to federal broadcast regulators will usually get the interference shut down... eventually. By then, the traveller who reported the interference has most often already left. Putting as much distance as possible between the affected device and the interference source is the only effective solution in the short term.

Getting access

In general, if using someone else's connection you will need to be careful about evading their filters. Doing so will almost certainly end your contract to use it if you're discovered evading a firewall through a connection you're paying for, and might upset someone even if you aren't. In some areas evading firewalls may be a criminal offence; this even applies in some Western countries when evading content filters aimed at blocking pornographic content.

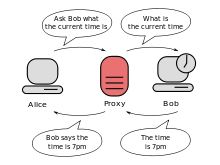

Proxy servers

The most common (and straight-forward) way to avoid blocks on certain websites is to connect to a proxy server and have that proxy server connect to the blocked site for you. However, the organisations doing the blocking know this, and regularly block access to the proxy servers themselves. If you are likely to need access to sites which are commonly blocked at your destination, it is most likely that you will be able to get access through an unadvertised proxy server you set up yourself or have a friend set up for you. There is a risk if you search for too many 'naughty' keywords (like 'counter revolution') you'll get the proxy taken down or blocked. Proxies that use encrypted protocol (such as https or ssh) are immune to this however, but the protocols themselves are sometimes blocked.

Some gateways (for example, that in China) are much more sophisticated than this: even when using a proxy server many sites are not accessible. One workaround is to use an ssh tunnel to connect to a proxy server outside the country via an ssh server, from a local port (e.g. 4321), then to connect to the proxy server like that.

If you're interested in seeing what might be blocked from inside the firewalls before you leave, it is sometimes possible to surf through a proxy server in the country you're going to be going to.

Personal VPN providers

Personal VPN (virtual private network) providers are an excellent way of circumventing both political censorship and commercial IP-geofiltering. They are superior to web proxies for several reasons: They re-route all Internet traffic, not only http. They normally offer higher bandwidth and better quality of service. They are encrypted and thus harder to spy on. They are less likely to be blocked than proxy servers.

Most VPN providers work like this: You sign up with the provider who gives you an account name and password. Then you use a VPN program to logon to their server. This creates an encrypted tunnel that re-routes your Internet traffic to that server. Prices range from €5 to €50 per month ($7–70), depending on bandwidth and quality. You might also have access to a VPN network of your workplace or university.

Loging on to a VPN is very straight forward on Windows machines since they have a built-in VPN program. As long as you know your username, password, and server address, you are likely to be able to use VPN from most Internet cafés. Since VPN is encrypted, there is no way for the connection provider to filter the sites you are accessing. However, VPN offers no protection against snooping software installed on the computer itself, so it's always a better idea to use it from your own laptop.

VPNs are routinely used by millions of business travellers to connect securely to their office computers or to access company documents. Therefore they are tolerated in all but the most repressive dictatorships. It is unlikely that simply connecting to a VPN will attract attention in China for instance. Since VPN providers are niche companies, it is also unlikely that their IP addresses are blocked. Warning: In a small number of autocratic regimes (Cuba, Iran) the mere usage of VPN is illegal and can land you in prison, no matter what you use it for.

Tor

Tor is a worldwide network of encrypted, anonymizing web proxies. It is designed primarily for the purpose of making an internet user untraceable by the owner of the site he/she visits. However, it can also be used for circumventing filters and firewalls. Unlike other methods explained in this section, Tor automatically rotates the servers used to access the internet, making it harder to discover your identity. However, there are only around 3000 Tor servers in the world, and their IP addresses are public knowledge, making it easy for governments and organizations to block them. Even so, new Tor servers join the network all the time, and if you wait patiently, you may connect to one that isn't blocked yet. Although the Tor Project introduced a function which allows for connection to unlisted bridges (no public database), preventing oppressive governments from easily blocking TOR.

Using Tor requires installation of software and usually also a plug-in for the browser.

SSH access

SSH (Secure Shell) is a good way of tunneling traffic other than http. However, you will normally need access to a server to use SSH. If not provided by your university, this can be expensive. Using your or your friend's home PC is not too difficult, but requires either a static IP address or a way to figure out the current dynamic one. The home PC should be on at any time when you want to connect (also after a power outage; have someone check it from time to time).

- if you control the server to which you want to connect, you can have your processes listen on ports that are unlikely to be blocked. A common technique is to have an SSH daemon listening on port 443, the secure HTTPS port, which is rarely blocked. This must be set up before going to the location with blocks on usual connections.

- if you have SSH access to a third server, connect via SSH to that server, and utilise SSH port forwarding to open up a tunnel connection to the target server.

Filtering junk

As your connections will be slow or expensive, at least from time to time, it may be worthwhile setting up some filtering mechanism, so that you get just the data you want. Some of the advice is easy to heed, some requires quite some know-how.

E-mail

For e-mail, most servers have junk mail filtering software at place. Often you can choose the level of filtering, sometimes set up your own filters. A common setup is that obvious junk is denied or deleted at sight, while possible junk is saved in a separate junk mail folder. If much junk gets through with your current settings, you could change the threshold, such that only real mail gets through, and check the folder for possible junk only when you have a good connection. You might want to temporarily unsubscribe from some high volume email lists.

With more elaborate options, you can direct non-urgent mail (such as that of many mailing list) to separate folders, likewise to be checked at a later occasion. If you are downloading all of the message when reading it (mostly, unless using a web interface), you could filter away large attachments (keep an unfiltered copy in a separate folder for later viewing). There is software to convert most documents to plain text, you might be able to use them to convert instead of delete the attachments in your filtered version. Configure your best friends' e-mail software such that they do not send HTML in addition to the plain text version of messages.

Any setup which uses amateur radio as a gateway to transfer e-mail from the open Internet will by necessity use a "whitelist" approach; any mail arriving at the Internet side from anyone not in an address book at the gateway is rejected. A "ham" radio gateway is an inherently-slow connection which is effective for getting small amounts of mail to disaster areas or watercraft at sea, but its operators are legally prohibited from sending commercial traffic on amateur frequencies — hence their zero-tolerance on gating advertising or spam.

If you use a web server for reading mail, you might want to limit the bells and whistles of the web interface. If this is impractical and you can filter your e-mail, you might want to use the web service only when normal e-mail access is blocked.

Proxies

There are proxy services providing filtered web content, mostly intended for web access with mobile phones, where heavy graphics, javascript and untidy HTML code can be a big problem. Some filters are available for personal computers, often targeted at advertisements and big brother features. With some browsers you can turn off images (especially third party images, which are mostly advertisements) and in some other ways restrict what pages are downloaded. A proxy is needed to filter unwanted content of the file to be downloaded, such as inline junk. To use a proxy is easily configured in the browser, but to choose and configure a proxy to your needs is more work.

The extreme lightweight solution is to use text based access (terminal emulator + SSH) to a computer with good connections (at home or wherever) running the e-mail and browser programs (e.g. alpine and elinks). This was the standard way to have Internet access in the old days of 14.4 kb/s, and still works at least for e-mail (some configuring may be necessary if you have friends writing their e-mail with office suites – and images have to be explicitly downloaded before view).