Common scams

There are common scams that occur in many places that the traveller should be aware of. These are designed to get your money or business from you under false pretenses. They fall into three categories: overcharging you, deceiving you or coercing you into paying for a service you don't want, and outright theft.

A scam is not necessarily a crime, and police might not have the will or legal ability to help out victims. In the worst case they may even be in on it and some ways of local law enforcement may indeed work with various forms of entrapment or trickery that might fall into a moral category not all that unlike some scams on this list.

Prevention is based on knowledge: researching your destination will both alert you in advance to scams in the area and let you know what the usual prices and truly good sights are so you will be less reliant on the approaches of helpful individuals when you're vulnerable.

At the same time, if you do get stung, don't be too hard on yourself: you were dealing with people who knew the location a lot better than you and with people who were out to deceive you. In some cases, you were dealing with hardened criminals. If you think what happened to you was illegal and the police are trustworthy, report it; otherwise, just chalk it up to experience. If you wish to make a theft-related claim against an insurance policy, you will generally need to make a police report within 24 hours and keep a copy for your insurance company. You will also need a police report to replace some stolen identity documents, such as passports.

The US State Department has a page warning of scams practised on travellers.

Avoiding scams

| “ | Fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, shame on me. | ” |

—English proverb | ||

Several bits of common sense may help you stay out of trouble without your needing to know exactly what scams are practiced in what areas:

Preparation

- If you have travelling companions, keep each other informed of the general outlines of your plans for the day

- Don't carry unnecessary amounts of cash or expensive items (e.g., Louis Vuitton purses, iPhones, etc.) around with you

- In high-risk areas, don't draw attention to the fact that you are non-local. Travel light, lose the string of cameras around your neck, dress as the locals do. Avoid typical "tourist" accessories, such as maps or backpacks. Don't be surprised if a vehicle with number plates from some faraway place and prominent rental car firm logos is targeted for break-in or theft as villains realize you have a long trip to come back to testify against them, or even a language barrier.

- Don't have your name printed on the outside of your bags in case someone approaches you using your name pretending to know you (use an opaque luggage tag if you must)

- Alcohol and other drugs affect your judgment and should be indulged in only among people you have good reason to trust.

- Research into your destination, its general layout, and the usual price ranges are helpful in avoiding many scams. When arriving in a new city, have a plan of where to go and be aware that airports, railway stations and the like are often places where touts and conmen wait for newcomers they can offer their "help" to.

- Knowing where you want to go and what you want to do and then sticking to that plan is a good way to avoid getting ripped off

- Knowing the language — even just basics — will make you look less "foreign" and be helpful in getting the help of locals when you're the victim of some malfeasance

Warning signs

- Each country has different high-crime areas. In general, low-income areas, touristed areas, stations for rail and other public transport and nightlife districts have higher crime risk than other areas. While airports themselves are often safe enough, the surrounding community may be dodgy; it's also likely to be far from the heart of the city. Many destinations have a motel strip on what used to be the main road into town; as these roads are bypassed by motorways, the lodgings (or even the local area) may go into decline or become a crime magnet. As each community is different, check the "stay safe" section of the Wikivoyage city article before deciding where to stay.

- Remember that astounding deals and amazing winnings are as unlikely as they seem and likely to be part of a scam.

- Be wary of any stranger who seems to be singling you out for extended special attention, especially if they are trying to persuade you to leave your friends or accompany them to an unknown area.

- Avoid anyone begging, particularly if they're using children to beg on their behalf (a common scam). In China, if you see a child begging, please post a picture of them online, as those children are often victims of kidnapping, and posting a picture online can make it easier for the children to be located.

- Being in any situation where you are among a group of strangers who all know one another, but not youself, provides them a great deal of power over you.

- Avoid sending money via Western Union or similar services to people or businesses you don't know.

- Be wary of attractive-looking strangers trying to raise your sexual emotions, including strippers, prostitutes and touts.

Reaction

- Always discuss and agree a price before you accept any products, services, or accommodation, and always have some proof of payment

- You are not required to be polite or friendly to anyone who refuses to leave you alone when you request it

- Nor are you required to answer getting-to-know-you questions from random people. These may just be friendly locals, but they might also be scammers looking for information useful to them.

- Walking on when offered some "incredible deal" might seem rude but really is par for the course and many locals have it down pat. Try to learn from them.

"Helpful" locals

These scams are based upon the idea of offering you help or advice that is actually deceptive, trusting that you will rely on the scammer's "local knowledge". They usually involve giving advice that results in you paying for something that you otherwise wouldn't or going somewhere you don't want to go. Some scams in which a helpful local offers to cut you a good deal can be outright fraudulent such as convincing you to buy fake gems for example but many simply get you to pay for something that you wouldn't pay for if you knew the area better.

One of the biggest traps of these kinds of scams is the desire to be polite to people who are polite and friendly to you; and the scammers know this. While you shouldn't become a hard-nosed nasty person, you should receive unsolicited offers of help with polite caution, and, when you are reasonably certain that you're being scammed, there's no need to be polite in fending it off: feel free to walk away or speak firmly at the person. Yelling for help could be necessary, but it will often just attract more (unwanted) attention. Pretending they don't exist, which entails not making eye contact, not walking faster, not saying 'hello' or 'no', will often humiliate them or tire them out without frustration on your part. Do not respond if they call you racist to attract your attention. Another common mistake is to say 'no thank you', in which case they have their 'foot in the door' tactic up and running and feel that they can engage in a conversation with you.

Another trap is the "too good to be true" offers: they are almost certainly not true.

Accommodation recommendations

Your driver or guide will tell you that the place you're heading to is closed, no good or too expensive and that he knows somewhere better. While this may be true, it's likely that the 'better' place is giving him a commission for referrals, and his commission is just going to increase your room rate.

You must insist on going to your planned destination. In some cases the driver will not drive you to your hotel even if you insist. In some places, taxi drivers will take you to the wrong hotel and insist it is the one you requested! Get the correct name because there are a lot of copies and similarities in their names.

To avoid being held hostage by a mercenary taxi, keep your luggage with you on the back seat so you can credibly threaten to walk out and not pay. They'll usually back down by the time you start opening the door—and if they don't, get a new driver.

The best thing you can do is avoid using taxis whenever possible. Before arriving in a new location have your accommodation pre booked, find out where it is on the map and see if there is alternative transport such as local buses to get to or near your accommodation. If you do need to book accommodation after arrival, book from a reputable source such as local travel agency or tourism office.

Attraction closed

You may arrive at a major tourist destination only to find a very helpful local near the entrance explaining that there's a riot/holiday/official visit at the place you want to go and it is closed. (Sometimes, taxi drivers are in cahoots with these helpful locals and will purposely drop you off to be received by them.) The local will then offer to take you to a lesser known but infinitely more beautiful sight or to a nice shop. Generally, the destination is in fact open for business: simply refuse the offer and go and have a look. Even on the very rare occasions that they are telling the truth, they may not be as helpful as they seem so it would be better to pursue your own backup plan. Just walk away from them and walk towards the main tourist entrance where they stop following you.

The opposite might in fact take place when arriving by car, especially in places like Rio de Janeiro, where scammers might ask for a fee to "keep your car safe" (a widespread scam in Brazil). While sometimes tourist attractions are in fact closed or under maintenance, scammers will state those are open, and demand a small fee in advance. Taxi drivers will also sometimes take a long route to a place and "forget" to mention the place is closed, then suggest an alternative attraction far away from the original place.

Art school

You are met in the street by people who say they are art students. They speak English well and invite you to visit their school. Then they will try to get you to buy one of their works for an excessive price. The "students" are usually attractive young women who are employed by the gallery to attract customers and to make the customers feel obliged to purchase "their" works to encourage them and repay them for their friendliness.

This scam is practiced in China, particularly in Beijing and Xi'an.

Insistent help

Sometimes locals will simply try to force themselves on you to help with a ticket machine, a subway map or directions. They might just be overly helpful but they may also be looking for and demand a small tip for their forced help. In general, be wary of anyone who forces their way into your personal space, and who starts doing things for you without asking you if you need them. If you have received help and then some coinage is demanded, it's probably easier to pay it. However, this kind of situation can also leave you vulnerable to substantial theft so be polite but firm, and then simply firm, by telling the person that you are fine now and that they should leave you alone.

A local eagerly offering to "help" take a photo of you might be unwilling to give your camera back, or might demand money for its return; likewise, anyone too eager to "help" you with your luggage may be intending to steal your valuables for themselves. A local may also offer to pose for a photo; only after you take the photo, they demand money.

Just been robbed

This scam involves persons approaching you and asking you if you know where the police station is. They will seem frightened and shaken and inform you that they have just been robbed of the money he needed to get back home which is very likely to be in a different city or even country. Again, they will get emotional and say the police perhaps won't be of much assistance and they will turn to you for help. Although they only expect you to happily hand over a small amount, the more people they con the more money they make themselves. This scam also takes the form of refugees escaping a war-torn country, a father who needs to get to a hospital to see his sick child and many other variants.

Border crossings

.jpg)

Poipet (on the border between Thailand and Cambodia) is a classic example of the border crossing scam. "Helpful" people will charge you for doing a useless service (like filling out your application form); "friendly" people will charge you twice the normal fee for obtaining a visa (which you can do yourself), crooks will tell you that you must change money at their horrible exchange rates (they will also tell you that there are no ATMs anywhere in the country), and tuk-tuk drivers will charge you some idiotic amount for taking you 100 meters.

The cure is simple: read up on any border crossing before you cross it, know the charges in advance, and don't believe or pay anyone not in uniform. Even then, try to ask another person in uniform to see if you get the same story.

Usually the Wikivoyage country articles have a description of the common procedures at all (major) border crossings in the "get in" section. In the case of huge countries, you may want to look in region and city articles as well.

"Official" asks for souvenir

After an official or someone dressed as one assists you at a transit station such as an airport or train station, that person will ask you for money from your home country as a souvenir. If you pull out less than what they want, they will use an overly friendly yet insistent manner to demand a higher amount, generally in notes. In some countries giving money to an official can be misconstrued as a bribe and can get you in deep water. It's best to limit conversation as much as possible and when asked for money, to feign ignorance or lack of cash. This has occurred in Malaysia and China.

Solicitation of money by photographic subjects

A local in a colorful costume offers to pose for a photo with a traveller, persistently asking "Want to take a picture?". The visitor takes one picture. The local then starts aggressively demanding money. The traveller objects, only to be met with a string of obscenities at best and physical force at worst.

The scam is that neither the price nor the intent to demand money is disclosed up front. Payment is only demanded after the visitor has taken the photo and it's "too late".

The operators are not licensed street vendors (they evade regulations by mischaracterizing their fee for service as a "tip" or gratuity, only to become rude, aggressive or violent when the victim refuses to pay). While they may appear as anything from bogus Sesame Street characters (who typically demand $2-5) to scantily clad women wearing little other than a thong and body paint (who take $10-20), they invariably do not have permission from the creators of any trademarked, copyrighted characters they're impersonating. As solicitations occur most often in high-traffic, touristed areas like New York City whose visitors are already subjected to begging, aggressive panhandling and various scams, their conduct reflects poorly on the city to outsiders.

While the best response to "Want to take a picture?" in some places is simply to walk away, parents travelling with children may find it very awkward to explain to tiny tots why the Cookie Monster was arrested in Times Square for pushing a two-year-old child to the ground (his mother refused to pay for a photo) or why officers carried an emotionally disturbed Elmo out of Central Park Zoo screaming obscenities (he was ejected for begging from the zoo's visitors).

Gifts from beggars

A beggar stops you on the street and gives you a "present", like tying a "lucky charm" around your wrist. Alternatively, they "find" something like a ring on the street and give it you. After a few moments of chit-chat, they start demanding money and follow you until you give them money.

Avoiding this scam is easy enough: remember what your mother told you when you were in kindergarten, and don't accept "free" gifts from strangers. This scam is particularly common in Egypt and Spain. In one variant occasionally seen in particularly large Canadian, American and Japanese cities, the beggars dress as fake monks to solicit these "donations".

Another similar scam involves overly pushy people who pose as collecting money for charity. This is particularly common in developed countries. Usually an old woman will approach you, tie a small flower to your shirt and expect you to "donate" money. They never say the specific charity, they often say "for the children." Inquiring about the specifics of their "charity" may help scare them off. Typically, if they have no name badges or even a charity name, it's probably not a real charity.

Before entering a situation where you might get hassled, set rules with yourself for how and when you will spend money, stick to the rules, and let other people know.

Dirty shoes scam

A shoe cleaner says your shoes need cleaning, and he points out that there is dirt on your shoes. When you take a look, there really is feces or any other kind of dirt on your shoe (a lot usually). He offers to get them clean again for a very high price. What you most probably did not recognize is that a few meters before that cleaner or a helper has thrown that very dirt onto your shoes.

This scam can also be combined with pickpocketing or distraction theft, as has been observed in Cairo and Delhi. A variant in Buenos Aires involves someone throwing mustard or some other paste on your coat and then the helper or a third person pickpocketing you and occasionally stealing your bag.

Begging for medicine to sick family members

This scam is practiced in parts of Africa, where it's well known that tourists travel with their own medicine such as penicillin or anti-malarial drugs. Beggars will approach on the street, telling a sad tale about their little daughter or son who is dying with malaria or some other disease. They will then ask you if they can have your medicine to save them. The sobbing story makes it difficult to refuse the request and they may accuse you of everything from racism to willingly letting an innocent child die. As soon as they receive your medications they will run away, presumably to save their daughter but in reality they will run to the local pharmacy to sell your medications. Expensive drugs such as Malarone may fetch up to $10 US per tablet.

This scam places a lot of emotional stress on the victims, but remember that if a child really was sick, it's highly unlikely that the father would be running around in the streets begging tourists for medicine. The child would have been brought to the local dispensary, and, if there really was a scarcity in drugs, you would probably be approached in quite a different manner. Also, remember that giving up hard-to replace prescription drugs might put yourself at risk if you were to contract any illness yourself. The cure is to not get soft-hearted so simply ignore the person and walk away.

Fake cops

You are pulled over by a vehicle that appears to be a police car, often unmarked. The supposed officer says you are about to receive a large fine and points on your license, but you can avoid this by paying a much smaller fee up front in cash. This is not a tactic used by law enforcement agencies almost anywhere. In countries without high levels of corruption, legitimate police officers care that the law is obeyed, not about the money they will receive. Police will either issue a real ticket that must be paid directly by mail or in person to the department, a warning in which no money needs to be paid at all, or they will let you go completely free. If you are in doubt, you have the right to request for another officer to come to the scene.

In another variant, a stranger at an airport asks an unsuspecting bystander to watch their bag or purse. The stranger leaves, returning with a police officer (or someone posing as one) who claims the bag contains drugs or contraband and demands a bribe to evade criminal prosecution.

It is quite easy to impersonate a police officer. Police vehicles are typically models that are also sold to civilians, and many of these models have not been redesigned in many years, so older ones can be purchased cheaply. Rotating lights like those found on the dashboards of unmarked police vehicles can be purchased easily in electronics or hobby shops, and police uniforms and badges can be purchased from uniform stores. Though a real officer knows the difference, a naive civilian (let alone a foreign visitor) does not.

In Serbia, at least, it is indeed possible and legal in some cases to pay 50% on the spot in cash to a traffic police officer or to pay 100% later in a bank or post office. On the other hand, in countries where police corruption is known to be a serious issue, a real police officer pulling you over may well be trying to extort a bribe—if you believe this is the case, you'll have to use your judgement and knowledge of the country to decide what to do.

"Better" exchange rate

Locals may offer better currency exchange rate than official banks or authorized currency exchange stores. It is best to avoid these offers since you may not know if you are receiving counterfeit bills or obsolete currencies that the government has phased out and no longer has any value.

Overcharging

These scams are based on your ignorance of the area and rely on getting you to pay well over the market rate for goods or services. Some will rely on a helpful local steering you to the goods, but others will simply involve quoting a high price to you. In some countries this is institutionalized: foreigners have to pay more even for genuine sights.

Getting a general sense of accommodation price ranges and the like is the best way to prevent being overcharged. In some places, it's assumed that you'll bargain down overcharged prices, in others, you will just have to walk away or pay up for goods although you should still challenge the amount in the case of a service if it is clearly overpriced.

Rental car claims of damage

When you rent a car, you are rushed through the process of checking for prior damage, including scratches; the agent may not be so happy about you taking your time to do it. The vehicle already has plenty of scratches or dents, so it is impossible for your eyes to catch all of them.

When you return the vehicle, you are hit with a rude awakening. The agency is accusing you of having caused damage to the vehicle, and is now holding you responsible. The agency has pointed out to you damage to a part of the vehicle it is difficult to notice, and it was probably there before. But they will not tell you that. You are charged hundreds, even thousands of dollars for it onto your credit card on the spot. They have probably charged this to multiple customers, even though the money is needed only once to repair it, and the amount they charge greatly exceeds the actual repair cost. In fact, they most likely will never repair it and will sell or trade the vehicle once their time with it is up.

Variants include charging clients for repairs which were never made, or charging for repairs at inflated prices. In some cases, the repair shop and the hire car agent conveniently turn out to both be controlled by the same person or entity, allowing claims such as $1000 for a windscreen replacement which was never done.

Tolls

Legitimate tolls use existing structures. But in some rural areas, primitive makeshift gates are set up on little traveled roads frequented by tourists, and money is demanded in exchange for passage. The appearance is given that it could be a "toll" or park entrance fee. In many cases you have few options besides paying and grumbling, but the mere threat of reporting the situation to authorities might do wonders in some cases.

No-change trick

If you make a payment that requires change, they will refuse it and demand that you pay the exact amount. If you are not very attentive however, they will "forget" to return your initial payment. It may seem strange not to notice this, but in a fast moving and confusing setting, it happens more easily than you think, especially if you are somewhat tired or intoxicated. Incidents like this do also happen in decent looking establishments, such as shopping malls and airport stores. A telltale sign of impending trouble is that the cashier will suddenly lose the ability to speak or understand a single word of English. If you still have all your money in hand, the best course of action is to abandon your goods and walk away.

In another variation, a seller will insist that he does not have change for the item you purchased and that you should accept goods (often of low-quality) in place of your change. If you ask to "cancel" the sale and get your money back, the seller may become quite pushy in insisting that you take the goods or try to make you feel guilty because he needs the money for his family or business is not going well. If paying with large bills, it is best to ask if the seller has change before handing over your money.

Yet another variation involves ticket windows at tourist sites. Ticket sellers will take your money, take a long time stamping your tickets and talking to colleagues, taking your ID as security for audio guides, etc., and simply "forget" to give you your change. They may give you some brief information, smile, and say "okay!" to distract you and send you on your way. Once you leave the window you have no chance of getting your change, so be sure to ask for it and not be distracted by their "helpful information".

Coin collector

While you're waiting in a public place such as a restaurant or bus stop, a friendly well-spoken local approaches you to engage in conversation. After some chit-chat, the individual then shares with you that he is a coin collector and asks if you would like to see his collection. The individual produces from his pocket a small collection of coins and explains with great feigned interest the country of origin of each of his coins. Mixed into the conversation will be questions about the type of money that you use in your home country and a seeming desire to know more. The intended outcome is that the unwitting tourist will show the pocket change they have with them from home and, if sufficiently fooled by the conversation, offer that the local person can keep it for their collection. After the conversation, the 'coin collector' will exchange the money for local currency.

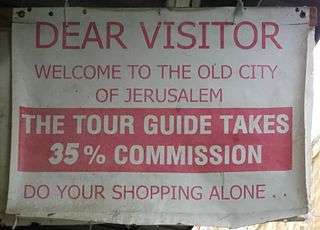

Commission shops

All over the world, but especially Asia, are shops that will give your driver or tour guide a commission to bring in tourists; some tours waste more time at these shops than they spend at actual sights. Often, these shops sell low-quality goods at exorbitant prices; they may claim to be selling handmade cottage industry products or to be child-labor free, but such claims are often false. It is strongly recommended to avoid buying anything from them, especially if you have been directed to the shop by someone.

Alternatively, decide what you want and then come back without a driver and bargain for a substantial discount. In Jerusalem this should be at least 35%, roughly the amount the driver gets. In some Chinese tourist trap stores, it should be at least 60%; the items are marked with "fixed prices" but the clerks are allowed to give up to 20% off and the guide gets 50% of the selling price so the "real" price is 40% of the marked one.

These places often have clean, western-style bathrooms, which can be hard to come by otherwise.

See the Shopping article for some alternatives that are often better than these shops.

Currency swap

If you are persuaded to buy souvenirs or other items from people selling on the street, look at the change you are given from the sale before putting it in your wallet: it may be in a different currency of similar appearance. For example, in China, a street-vendor may hand you a 50 ruble note in change instead of 50 yuan; the former is worth one tenth as much as the latter. In some areas, you may get outright counterfeit currency. Also be careful that the notes you receive are not ripped or damaged as these may not be accepted elsewhere. It is also possible for the vendor to outright steal bills from you in the process of "exchanging" money.

Often, bad money drives out good. Many obsolete currencies which are similarly-named to the modern currency look official but are worthless; governments fuel inflation by printing too much money, then create a "new" currency which merely lops a few trailing zeroes off the denominations of the worthless "old" currency. Governments have also "demonitised" specific notes, deliberately rendering them no longer valid. There are also some countries (such as Cuba) which officially have (or had) two currencies – the Cuban convertible peso (CUC) is more valuable than the regular Cuban peso (CUP), creating opportunities for bait-and-switch on the hapless voyager.

Calculated price

Precious metal items such as gold bracelets are sold as 'dollars per gram' in some countries. Comparing the price between shops and then against the current gold price makes the practice appear open and transparent, so much so that you may rely on the seller to do the calculation. It won't be till later, if at all, that you will realize that the price you were charged is much more than the calculated price.

Fair exchange

A vendor may claim to be willing to accept your home currency for a purchase (and most travel venues on an international boundary do so) but their exchange rate is at least 10% worse than any local bank or a dedicated bureau de change. For instance, "US dollars accepted here" by a merchant at $1.10 (when the local currency is trading below eighty cents on the open market) is no bargain. Sub-prime cheque cashing businesses are also infamous for deliberately unfavorable rates on currency exchange.

One pitfall in this respect is dynamic currency exchange: the vendor on a card-paid transaction offers to do the conversion for you and bill your card in your home currency. In most cases, it's best to say "no" and refuse to complete the transaction if the vendor insists, as the exchange rate offered by the merchant is almost invariably worse than whatever's offered by default by your card's issuing bank or credit union. This is a common scam in Europe. The card terminal may be handed to you with the choice of local or your home currency. Always pay in the local currency as your credit card company will invariably provide the better exchange rate. If the vendor has already selected your home currency, cancel the transaction (red key) and ask them to enter again in local currency.

Gem and other resale scams

You are taken to a jewelry shop and offered a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to purchase gemstones or jewels at special discount prices. Another customer in the shop, well-dressed and perhaps from the same country as you, tells how he made incredible profits last year by reselling the gems and is now back for more but to hurry as the sale ends today and you have to pay cash.

Of course, once you get back home and try to sell your booty, it turns out to be low-grade and worth only a fraction of what you paid for it. This scam is particularly prevalent in Bangkok, but variations on the theme with other products that can supposedly be resold for vast profits are common elsewhere too. Another variation involves you exporting the gems for a supposed 'commission' in exchange for the scammer taking a photocopy of your ID cards and/or credit cards, which can of course be used to make a tidy profit via identity theft.

Counterfeit items

Unfortunately for the traveller, counterfeiting isn't limited to the manufacture of "Relox" watches or knock-offs of random overpriced luxury goods from CD's and DVD's to watches, clothing, bags and cosmetics. In some regions, branded prescription medicines are prone to being copied by rival manufacturers. Knock-offs vary from legitimately useful generics to poor copies with the wrong amount of an active ingredient; many are diluted and some don't work at all. Outdated medications, which can be unreliable, have a knack for turning up at inopportune moments in out-of-the-way places. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates indicate one million deaths are tied to bogus medicine, with fake anti-malaria tablets in Africa of particular concern.

American import law prohibits bringing more than one of any counterfeit item into the country and requires the items be declared. This is especially important when travelling back from Asia, where most counterfeit goods originate. It's assumed that if you are buying more than one, it's for illegal resale. One counterfeit Rolex for your possession is legal, but two fake Rolexes are illegal and subject to thousands of dollars in fines.

Counterfeit currency is also an issue in some regions, particularly in Asia. North Korea is accused by the CIA of printing very convincing (but bogus) US currency, known as "supernotes", for export within the region.

Cruise ship art auctions

Passengers are lured to auctions of supposedly investment-grade, collector art. Free champagne flows like water. The auctions may or may not be conducted by licensed auctioneers and may not adhere to standard auction practices. Since the sales take place at sea, making claims under consumer protection laws is difficult. Buyers may have little recourse if the art is misrepresented. Furthermore, in traditional auctions a bidder buys merchandise which is for sale right-here, right-now. Cruise ship auctions sell the art on display, but the winning bidder actually receives a different (but supposedly equivalent) piece which is shipped from the auction company's warehouse. Many art buyers at cruise ship auctions have later found that their shipboard masterpieces were worth only a fraction of the purchase price.

Non-exportable antiques

Buying expensive antiques anywhere is risky. Even experts can sometimes be deceived by fakes, and a naive buyer is at great risk of being overcharged nearly anywhere. An additional complication arises in the many countries which, quite understandably, have various restrictions on export of relics of their culture. Egypt and India, for example, have strict rules on export of antiquities and China requires a license for antiques. In Peru it is forbidden to export relics and to buy a relic requires a license of the Ministry of Culture, so always check in the official tourist information office (iperu).

Check the laws in any country you visit before buying antiques. Otherwise, you might have your purchases confiscated at the border and be hit with a hefty fine as well. In some countries, licensed dealers can provide paperwork that allows export for some items, but bogus documents are sometimes provided. Try to deal with someone respectable and traceable.

In some countries, the whole thing becomes a scam. Instead of preserving the confiscated "heritage" items, corrupt border police may sell them right back to the tourist shops so that the shops then sell them to another unsuspecting traveler.

Your own country may also apply import restrictions to items such as animal pelts (for a long list of species, some of which are not actually endangered) or anything containing ivory. Know before you go.

Plastic bag code

In some countries where haggling is common, people at markets may have an arrangement where they will put purchases in different colored bags to signal how much a customer has paid, allowing other vendors to charge accordingly. For instance, at a certain market, a white bag may indicate that a customer paid the usual price whereas a blue bag may indicate that they paid a higher amount - vendors will ask a higher price if they see someone carrying a lot of blue bags. Different markets have different color codes, and some may have several stages of overcharging.

To avoid this, try to figure out how much the usual prices for things are before making your purchase and haggling the price aggressively if they are charging too much, and putting purchases in a backpack or durable shopping bag rather than using the plastic bags provided.

"Low cost" airlines

While low cost airlines are legitimate and often genuinely cheaper operations, some of their (usually totally legal) business practices are similar to scams. A thing that is so common that it shouldn't surprise you is the quoting of prices "from" a certain amount of money. Sure the ticket for London to Milano "from" 19 Euros sounds tempting, but those prices usually refer to a small contingent of tickets that you have to be quite lucky to ever see, let alone get. Besides that prices are almost always quoted for one-way fares (whereas traditional airlines often quote round trip ticket prices) and don't include a variety of fees and taxes. If you really want to go one way on a day of the week that sees little traffic and have little or no luggage and are willing to take it with you carry-on, you may well get the fabled low rates, but otherwise you should read the fine print very carefully.

Some low cost airlines are notorious for outrageous fees, such as 50€ for printing a boarding pass or $100 for half a pound of excess baggage. Another common trick is for "low cost" airlines to fly out of secondary or tertiary "airports" (often converted former military airbases) that - especially in Europe - are not well connected to any sort of public transport and more or less in the middle of nowhere and then proceed to give them deceptive names like "Barcelona"-Girona, "Düsseldorf"-Weeze, "München"-Memmingen, or "Frankfurt"-Hahn, even though those cities are a hundred or more kilometers from "their" low cost airports. In the US low cost airlines often fly to airports closer to the city they are named after, but ridiculous surcharges may apply as well. That being said "legacy" airlines have now copied several of the low cost airlines' business practices, especially on short distance routes and especially in the US.

In short: read the fine print carefully, don't order any "extra services" you won't need (a 10€ insurance for a 20€ flight is getting ripped off and 15€ seat reservation for a 50 minute flight is most likely not worth it) and for god's sake jump through all the hoops the airline makes you jump through, lest you be charged ridiculous amounts for paying with the wrong kind of debit card or sitting in the wrong seat or failing to print out a boarding pass in the right format on the right type of paper.

Coercion

These scams rely on trapping you in a bad situation and forcing you to pay money to get out of it. They're best prevented by avoiding the situation; once you're in it, you may well have no option but to pay whatever it takes to get out of it safely. Many of these scams are bordering on illegal.

Free tours

You are offered a "free tour" of a shop or factory way out of town. Your driver may then suggest that you'll need to buy something if you want a ride back. The best prevention is avoidance as if you're stuck out there you might well be compelled to do as he 'suggests'. Don't accept any kind of lift or offer of a tour without having a basic idea of where you're going and how you will be able to get back if your driver deserts you. Of course, if you are strong and assertive from the beginning in dealing with any suspicious characters, you can limit your chances of being involved in this kind of sting. However, always bear in mind that the perpetrator may be carrying a knife or be willing to assault you if the situation arises.

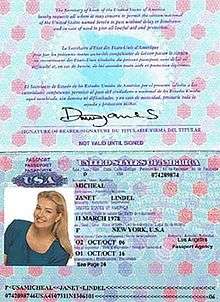

Passport as security for debt or rental

- See also Theft#Passport and identity theft

You rent equipment like a jet ski or motorbike. You are asked to give your passport as a security guarantee. After returning the rented goods, the owner claims you damaged them and will ask for exaggerated prices to compensate or claim to have "lost" your passport (later the police or lost property office want a substantial "donation" for its return). If you do not agree, they threaten to keep your passport. This scam is used in almost all tourist resorts in Thailand and is very effective.

Never hand over your passport as a security or guarantee in any circumstances. Pay cash (and get a receipt), or hand over something comparatively worthless, like your library card. You can also try going elsewhere (often the threat will be enough).

Note that most passports include wording such as this (direct quote): "This passport is the property of the government of Canada ... If your passport is surrendered to any person or agency outside the Canadian government (e.g. to obtain a visa) and is not promptly returned, report the facts to [an embassy or consulate]." At least in principle, no-one — except a foreign government, a travel agent or an employer who needs it to arrange a visa, or someone like a hotel or airline who want it briefly to check you in — can take a passport away, and anyone who does is in violation of international law. Your government can press the host government to fix the problem, and that government in theory has no choice but to do so. Of course, in reality it is far more complex; your government may not be helpful, the host government may ignore them, local cops may ignore a request from the capital, or they may not have an effective way to pressure whoever has the passport.

Overpriced street vendors

You decide on a whim to buy a piece of one of the massive cakes covered in nuts and fruits that are a fairly common sight in the tourist-laden parts of cities in China. You ask the price, and the man tending to the cake tells you it depends on how much you want. You show him how much. Immediately, he slices the cake, weighs it out, and gives you an extremely high price. He tells you that since he already sliced the cake, you have to buy it.

The best thing to do in this or any similar situation is probably to leave your purchase and just walk away. If they hassle you, threaten to call the police. Like the art school scam, this ruse depends on using your guilt to coerce you out of your money.

Rigged gambling games

This comes in many forms, from the three-card monte cup shufflers of Europe's city streets to dodgy gambling dens in the backstreets of South-East Asia. In most cases, the target is alone. The conman strikes up a conversation and then claims to have family in the target's home country. After some "friendly" conversation, the target is then invited to a card game or other some type of gambling: just for "fun" of course.

The target is taken somewhere far from the tourist area. After doing a few "practice" games, then they start to play for real. Of course, the game is totally rigged. After losing, the target will find his "friend" not so friendly anymore, and then a massive amount of money will be demanded (often totaling in the thousands of dollars). Violence might be used to settle the debts. In some jurisdictions gambling of any kind is illegal.

Tourists are by no means the only targets for this. Professional Chinese-Canadian scammers routinely take huge amounts from Chinese overseas students in crooked mah jong games, for example.

Do not gamble for money with strangers or outside of licensed and well-regarded gambling venues.

Cash on the sidewalk

As you stand on the sidewalk studying your map or guidebook, a passerby will point to a roll of bills, wallet, or gold jewelry on the ground nearby and ask if it is yours. They pick it up and offer to split the stuff with you. If you agree, a couple of heavies will soon appear demanding their money back, much more than you originally "found" of course. This scam is most common in Russia and Ukraine but it's also used in France.

Free hair salon treatment

Most commonly in Asian countries, a good-looking hair dresser would stand outside the salon and pass out coupons for a "free" shampoo hair wash and "free" head massage. Even if you decline, they will continue to be persistent. As soon as they succeed in seating you down in a salon chair and start wetting your hair, they'll explain how damaged your hair is and which specific products will help. The prices are absurdly set and often 2 to 3 times more expensive than in the US for a similar salon treatment. It will be much more difficult to refuse then after they've stroked up a friendly conversation and compliments. The best way to avoid this is simply tell them you've just had a haircut and are not interested.

Theft

Various scams are outright theft:

- Distraction theft, in its various forms, usually involves one villain distracting the victim while an accomplice steals items of value.

- Payment card thefts include various schemes to steal credit card numbers (card skimming) or copy the PINs and magnetic strips of ATM/cash-point cards. In some schemes the card itself is stolen, in others the card information is stolen and used to make fraudulent transactions.

- Pickpockets steal items (usually wallets, passports or other valuables) from people's clothing and bags as they walk in a public place.

See the main articles on pickpockets and theft.

A few scams involve putting you in a position where someone can take your money by force.

Friendly locals wanting to go out for a drink

While walking down the street you may be approached by attractive friendly locals wanting to go out for a beer or a drink. Then they tell you the drink costs way more than it actually does. Or worse, they just wait for you to become inebriated (or tamper with your drink to drug you in some manner) and take your money. See also clip joints, below.

Maradona

The Maradona is a scam that is very common in Romania, especially in the capital Bucharest. Someone will approach you and attempt to engage you in a conversation (in English), usually about something vaguely illicit. Seconds later, two men will appear in plain clothes but flashing legitimate-looking police badges. They will accuse you and your "new acquaintance" of some illegal activity (usually 'currency swapping'), and demand to see your wallet and/or passport.

Do not hand them these things! Keep your documents and belongings in your pocket and out of sight.

Walk away, or yell, or tell them outright that you do not believe that they are the police or suggest that you all walk to the lobby of a nearby hotel (or police station) because you are not comfortable taking out your wallet or papers in the street. These conmen thrive because the police fail to enforce laws against nonviolent crime and some foreigners are easily fooled. They will not physically attack you: the treatment of violent offenders is severe (these men are professionals, and they would never be foolish enough to chance a physical attack). Do not threaten or try to fight them.

There is a more violent variant of this, observed in Cartagena (Colombia), where you are offered drugs to buy. If you do so, fake police officers emerge immediately and will demand for you to pay a huge fine. They will take you to the nearest ATM and make you withdraw as much money as you can and may even kidnap you.

Car trouble

People will approach you on the street and tell you that their car just ran out of fuel or is broken down and is only a few blocks away. They'll usually first ask for money for gas. If you don't believe them or try to walk away, they may beg you to come with them to the car to see that they are telling the truth. They may offer you some kind of security such as their jewelry and be well-dressed and plausible seeming.

Do not give people money in these and similar scenarios. Do not follow them to where they claim their car is. If you suspect they are really in trouble, you could report their predicament to police.

Street brawl

You are walking down the street alone and all of a sudden you see many people attacking one person (sometimes an old man or a woman). When you want to help, people will make photos of you and will blackmail you afterwards to go to the police. Now you find out that the attacked person, the attackers and the photographer are a group. They will blackmail you for large amounts of money, because if they go to the police, you most likely need to leave the country (for example in China).

Avoid this scam by following this piece of common sense: It is never wise to engage in fights. If you witness a fight, your best bet is to either walk away or alert the police if they're trustworthy. NEVER get involved yourself. Laying your hand on a local may result in deportation in some countries.

Payment card scams

- See also: Theft#Payment card theft

Your credit card number, your debit card PIN, or even the card itself is an obvious target for theft and fraud. Some of these scams are distraction thefts (one person distracts you while the other steals your card), some switch a merchant's debit keypad for a tampered or fake version, some add extra hardware to ATM cashpoints to skim the magnetic stripe from payment cards.

In one variant (which appears occasionally as a taxi scam) a vendor asks for payment by debit card and presents a keypad to enter a PIN. The vendor then hands back a card that looks like the one the voyager originally provided... but it's the wrong card. The scammer now has your card, the keypad was rigged to steal your PIN and the thieves go on a spree from cashpoint to cashpoint, emptying your account. Another variant is the restaurateur who wanders off with your credit card, either to secretly copy your card number or to take out a cash advance at your expense.

Counterfeit tickets and stolen goods

There are multiple variants; someone on-line claims "50% off" WestJet tickets to attendees of a particular convention, but the tickets were purchased with a stolen credit card which is quickly red-flagged by the airline; someone lists hard-to-find tickets to a rock star's concert on Craiglist, but these were printed as an elaborate forgery and fifty other unhappy fans are gathered outside the stadium with their equally worthless "tickets"; someone lists a mobile telephone on Kijiji which a mobile carrier soon places on a national blacklist, so that its electronic serial number (IMEI) can't be subscribed anywhere. If the item was purchased from a web listing and handed off in a public place, the seller is later conveniently nowhere to be found. Another variant is an otherwise-valid ticket which the original issuer won't allow the original buyer to transfer (such as a Disneyland multi-day pass with a few days left, which turn up outside the parks often). The items don't have to actually be stolen; it is not unheard of for a mobile provider to place an IMEI on a blacklist in an attempt to get leverage against a subscriber in a billing dispute, with the subsequent owner of the handset victimized.

Event scams

Scammers don't rest during the holidays. Sometimes an event organiser will pop up just long enough to announce a big Halloween or New Year's Eve bash, with pricey tickets for admission sold in advance. The buyers of these tickets only find the event doesn't exist, isn't as advertised or that the tickets are counterfeit on the day of the event; at that point, because the vendor was a short-lived seasonal, pop-up operation, they're nowhere to be found. Another variant is a mail order vendor peddling seasonal merchandise (such as Halloween costumes) that either doesn't arrive, are not as advertised or only turn up after the event is over. Try to return the two sizes too small Halloween garb that didn't arrive until November, and the seasonal pop-up merchant is conveniently gone — closed for the season.

There's nothing inherently tying these scams to one specific time of year; the various holidays just provide convenient marketing opportunities.

Prostitutes

Sexually attractive people are a fine distraction, and conspicuously available ones even more so.

However, sampling the local streetwalkers puts you at risk of crime. Prostitutes can be used as bait for a variety of scams:

- leading you into an armed robbery

- having a confederate go through your clothes while you are out of them

- taking your hotel room key, which is turned over to burglars or thieves

- "cash and dash", where a provider accepts payment for services that are never provided, then leaves

- advance fee scams, where the pimp (or a thug) arrives without the service provider and demands the cash up front - before vanishing with the victim's money in pocket and no service provided

- a bogus "outraged family member" (or cop) appearing and needing to be bought off; alternately, this person's arrival is carefully timed to occur immediately after the provider has accepted payment and before any service is rendered, as effectively a "cash and dash" scheme

- hidden cameras and eventual blackmail

In many instances, the prostitutes themselves are not there of their own free will, but are victims of people traffickers, organized crime, or under the influence of street drugs.

In almost all cases, the presumption is that victims will not call police; the clients are either ashamed to have to pay for a 'companion', afraid to be outed to a spouse on whom they are cheating, fearful of violent retribution by those running the scams or afraid of legal prosecution as even jurisdictions which nominally do not criminalize prostitution may still outlaw a long and arbitrary list of related activities.

Even if you do not allow one to lead you anywhere, streetwalkers can be dangerous. A person who brings one to his hotel is quite likely to miss his watch or wallet in the morning. In some countries, such as China or 48 states of the USA, prostitution is illegal and hotel staff may have the local police arrive at your room door not long after you check in with one.

In countries where prostitution is not fully legalized (and even in some cases where it is), such establishments may have links with other forms of criminal activity, notably various types of gangs, drug dealers and money laundering. A few are clip joints; as legal restrictions in many jurisdictions make providers claim to sell "massage", "companionship" or just about anything except actual "full-service" prostitution, these folks will gladly take the victim's money, then claim the payment was "just for the massage" and demand more money repeatedly. The mark is unceremoniously ejected from the premises (with no actual service provided) once his wallet is empty.

Taxi scams

- See also: Taxis

Airports, stations and other places where people arrive in a new city are favorite places for all kinds of touts offering their (often overpriced) services. This includes taxi drivers and people pretending to be taxi drivers and if you're dealing with a dishonest person, the least bad thing that could happen is that you'll be driven to your destination but at an outrageous price. Therefore; if you need to travel by taxi from there, go to the official taxi line.

Scenic taxi rides

Since you don't know the area, taxi drivers can take advantage of you by taking a long route to your hotel and getting a large metered fare. The best prevention is knowledge: it's hard to learn a new city well enough to know a good route before you arrive for the first time. Always ask your hotel roughly what the taxi fare should be when you book or to arrange a pickup with them if they offer the service. Often you can negotiate a fixed price with a taxi before you get in and ask what the range of fare to your hotel will be. Good taxi drivers are on the route to your hotel every day and can give you a very accurate price before you or your luggage get into a cab.

Taxis not using the meter

In cities where the taxis have fare meters, drivers will often try to drive off with tourists without turning the meter on. When you arrive they'll try and charge fares from the merely expensive (2 or 3 times the usual fare) to fares of hundreds of US dollars, depending on how ambitious they are. If you're in an area known for this scam and you know where you're going and want them to use the meter (rather than arrange a fixed fare), ask them to turn the meter on just before you get in. If they say that it is broken or similar, walk away and try another taxi. They will often concede: a metered fare is better than no fare.

However, an ambitious traveler can actually work this scam in their favor, as in certain countries where meters are required (China) the passenger cannot be forced to pay for an "informal" (that is, unmetered) taxi ride. A tourist is therefore free to walk away after the ride without paying anything at all: once you step out of his vehicle, the driver will have no proof of transaction to show the police. This tactic is, however, not recommended for use by the weak of heart but can save you money as a last resort.

Using the wrong metered rate

A related scam is using the wrong metered rate: setting it to a more expensive late-night setting during the day. You need location-specific information to prevent this one. A typical rip-off scenario involves a device known as "turbine". By pressing specially installed button (usually on the left of the steering wheel, or next to the clutch pedal) the driver starts the "turbine" and fools the meter to charge much faster than the usual speed. The change in the charging speed is obvious, so dishonest drivers talk and show around a lot, to make their passengers keep an eye off the taxi meter. The best way to prevent the driver from starting the turbine is to keep an eye on the meter at all times.

When suspicious, ask the taxi to drop you off at your (or any) hotel lobby. Security at most hotels can intervene if you are being overcharged.

Luggage held hostage

Watch your luggage as it is loaded! Get into the cab after your luggage is loaded and out before it is out of the trunk. If you put your luggage in the trunk, they might refuse to give you your luggage back unless you pay a much higher price the actual fare. Remember to always write down or remember the taxi number or driver's number in case of problems and keep your luggage in your hand at all times if possible. Often, just writing down the taxi number will make them back down if they are keeping your luggage hostage, but be careful that they are not armed or are trying to rob you by other means than just driving away with your luggage.

"Per person" taxi charge

Taxi, tuk-tuk, or auto-rickshaw drivers will agree on a price. When you arrive at your destination, they may or may not tell you that the vehicle is a share vehicle, and they will tell you that the price quoted is per person. The tricky thing is that a per-person charge (or a flat rate plus a per person charge) is standard in some cities and countries, so it's important to research the destination beforehand and make sure you and the driver are both clear on what the price means before you start riding. If you know the driver is trying to scam you, you can almost always just give them the agreed-upon fare and walk away. Just make sure that you have the correct change before departing as in many places drivers are known to come up with any excuse it takes to charge you extra.

Food and beverage scams

From the barkeeper who charges full price for watered-down drinks to the restaurateurs who give themselves generous tips using their diner's payment cards, there are various schemes in which travellers are overcharged for food and beverage service.

Dual menus

A bar or restaurant gives you a menu with reasonable prices and takes it away with your order. Later they present a bill with much higher prices. If you argue, they produce a menu with those higher prices on it. This scam is known in Romania and in bars in China among other places. The best way to avoid this is to stay out of sleazy tourist bars. Another option is to take a picture of the menu with your phone camera. If the restaurant argues, you can always tell them that you want to send it to your friends because they otherwise wouldn't believe the prices are so low. You can then proceed to take a picture of the food for your foodie-blog (which might come in handy if the items on your bill don't match the items you ordered or were served).

You could also try hanging on to your menu or paying when your drinks or food are delivered, preferably with the right change. Watch out for asking for a menu in English, as the prices on the menu are sometimes higher than the menu in the native language, although because of the difficulty of navigating a foreign-language menu and the likelihood that the price even with the foreigner surcharge is still pretty low, non-Mandarin-readers may want to write this off as a translation fee. Another variant is the venue which lists an absurdly-inflated price, then claims to offer a "discount for locals". In some places where there is a common parallel currency (usually US Dollars or Euros) there might be a menu with prices quoted both in local currency and the parallel currency. Prices in the local currency may be significantly lower, especially if there is high inflation, so know the up to date exchange rate. A general rule of thumb is: unless inflation is rampant you will be better off paying lower prices and using local money. In some rare cases "hard" currency may get you things that local money can't buy, but in some of those countries using foreign money or exchanging at the black market rate may be various shades of illegal.

A variation of this scam is ordering off the menu, where your waiter will offer you a "special" that is not shown on the menu. The meal will not be very special but will come with a price considerably higher than anything else on the menu. Also, touts and barkers might advertise low-price offers - or an attractive discount is prominently announced by signage outside the restaurant, but then the bill is calculated with normal prices. If an offer seems suspiciously cheap, read the fine print and once again: If it sounds too good to be true, it probably isn't.

Pane e coperto

.jpg)

A restaurant indicates one price on the menu, but when the bill arrives there's an extra undisclosed cover charge. Restaurants in Italy, where cover charges are common, call them "pane e coperto", an extra charge for bread ("pane") and service ("coperto" or "servizio"). Cover charges are normal in some countries, but they should be disclosed up front. Otherwise, they're generally illegal (and some restaurateurs will try to slip this past by burying a one-line "service not included" in a lengthy menu); it also never hurts to check whether the restaurant is giving you a proper receipt for this extra money (and, presumably, paying the taxes on it). Often, a restaurant will attempt to slip extra charges onto the bill for visitors, but not for locals.

Unlisted cover charges

A fast-talking man (or attractive woman) standing outside a strip club will offer you free entry, complimentary drinks and/or lap dances to get you inside the club. They'll often speak very fluent English, are able to pick your accent, and be very convincing. Of course, they are good to their word with the free drinks and dances, but what they won't tell you (and what you won't know until you try to leave) is that there's a "membership fee" or "exit fee" of at least €100. There'll also be security waiting at the door for non-payers.

A variant of this is practiced in Bangkok, where touts with laminated menus offer sex shows and cheap beer. The beer may indeed be cheap, but they'll add a stiff surcharge for the show. Similarly in Brazil, expect to pay an extra 'artistic couvert' if live music is playing. No-one will warn you of this because it's considered normal there. Ask how much it is before you get seated.

Clip joints

You're approached by an attractive, well-dressed, local gentleman or woman, who suggests going for a drink in a favorite nightspot. When you arrive, the joint is nearly deserted, but as soon as you sit down some scantily clad girls plop down next to you and order a few bottles of champagne. Your "friend" disappears, the bill runs into hundreds or even thousands of dollars, and heavies block the door and flex their muscles until you pay up. A variant is the "B-girl" or bar girl scam, where organized crime recruits attractive women to go into legitimate bars, seek out rich men who display expensive shoes and watches and lure them into "after-hours clubs" which are not licensed (or not otherwise open to the public) and which charge thousands of dollars to the drunken victims' payment cards. Often, the victims are too intoxicated to remember exactly what happened.

This is particularly common in Europe's larger cities, including London, Istanbul and Budapest. Florida is problematic due to a state law which directs police to arbitrarily force victims to pay all disputed charges and then attempt to recover the money by filing a dispute with the credit card issuers—an uphill battle. The best defense is not to end up in this situation: avoid going to bars with people you just met, pick the bar yourself, or at least back out immediately if they want to go somewhere that is not packed with locals. In Istanbul this scam is also common with places packed with locals, where they scam the tourists, but not the locals, as it is a difficult and time consuming process to get the police to do anything. It is best to pay by credit card, so have one ready so that if you do end up in this situation, you can pay by credit card to get out and then cancel your card and dispute the bill immediately. While police in some jurisdictions are unlikely to be of much assistance, filing a report may make it easier to get the charges reversed.

A variety of this scam is extortionate tea ceremonies in Beijing and other cities in China. You will be approached by women who speak very good English, spend 30 minutes in conversation with you and invite you to have tea with them. The tea house they take you to will be empty, and you will end up in a situation of having to pay a huge amount of money for a few cups of tea. This is incredibly easy to fall into, as the scammers are often willing to spend considerable time "chatting you up" before suggesting going for tea. The best way to avoid this would be to not engage in conversation in the first place. Failing that, refuse to go with them to have tea, or if you find yourself having been fooled as far into going to the tea house with them, insist on leaving as soon as you can (e.g. fake receiving an urgent phone call from your friend), and ask for the bill (as each different variety of tea you drink will doubtless add up to the final cost).

Lodging scams

Some hotels and motels may be unscrupulous. While independent establishments may be a higher risk (there is no franchiser to whom to complain), there are cases of individually owned franchises of large companies engaging in unscrupulous practices. More rarely, the chain itself is problematic or turns a blind eye to questionable hidden charges; in one 2014 incident, the US Federal Communications Commission fined Marriott International US$600,000 for unlawful, willful jamming of client-owned Wi-Fi networks in one of its convention centres.

Most hotels are honest, and you will not encounter these problems. These are the minority, but the customer should be watchful, and should be aware of what signs to look out for.

It is not uncommon for a guest to check into a hotel when they are tired after many hours of travel, or to check out when they are in a hurry to catch a plane or get to another destination. At these times, a customer is unlikely to argue and therefore more likely to be suggestible or to cave. Guests in the middle of a stay are also unlikely to argue about being cheated due to fear of retaliation from management.

Advance fee scams

You book a room in advance, presuming that you will pay for it on arrival. Soon after, an inquiry arrives - presumably from the hotel - asking that you pay in advance, usually by wire money transfer. You pay, you later show up to find that the hotel denies all knowledge of having requested the wire transfer and demands to be paid again, in full. A less extreme form is that even when you book the hotel in advance, the hotel may attempt to charge for more nights than originally agreed to. They may also insist on payment in cash.

Odds are the hotel or middleman has breached confidential data, either through deficient security or a dishonest worker, giving a scammer the opportunity to hit travellers up for money in advance, take the cash and run. The scammer, officially, does not represent the hotel and the hotel glibly denies that it was their (or their reseller's) negligence which compromised the data; the longer they deny everything, the lower the chance of their being sued. Not only are you out the money, but some scammer likely has your home-country address and info (maybe even the payment card used to make the initial reservation) and can steal from you knowing that you are abroad and unable to do anything about a theft from your home or your payment cards until you return.

In another variant, you see an attractive cottage for rent in an on-line advert, pay to reserve it in advance and then show up - luggage in hand - to see Papa Bear, Mama Bear and Baby Bear seated at their breakfast table wondering why some scammer on Kijiji just rented the cottage they're living in to Goldilocks (you, the unsuspecting traveller) in an advance fee scam. As the scammer placing the ads has no tie to the property, they conveniently are suddenly nowhere to be found and the money is gone. Somewhat more audacious scammers rent out nonexistent cottages, often next to such small roads that they don't show up on Google Street View. Once you're there, you'll find out that there's only wilderness where the cottage is supposed to be, and the photo of the cottage was copied from somewhere else.

Amenity fees

It is the norm to receive amenities already in the room at the quoted rate, regardless of whether or not they are used. But some facilities have been known to charge customers additional fees for use of certain amenities, such as a refrigerator, microwave oven, coffeemaker, iron, or safe by surprise. Often WiFi access is advertised on the website, but its high fee is not mentioned. Some will charge if it has been used; others will charge even if it has not been used. In any case, this is a way to nickel-and-dime the customer. This should be clearly advertised before the reservation has been made; unfortunately, groups representing hoteliers (such as the American Hotel & Lodging Association) have lobbied governments aggressively to avoid a crackdown on so-called "resort fees".

Hoteliers are infamous for padding invoices with "incidentals", hidden charges for anything from telephone calls at inflated prices, to high charges for parking, to overpriced pay-per-view television programming to single servings of bottled water at a few dollars each. It is not unheard of for a hotel to charge high fees to call toll-free numbers or block services like "Canada Direct" that let you reach an operator in your home country; some even redirect the number to a competing provider who immediately asks for a credit card number. Some venues may illegally jam mobile telephone data connections to force you to use their overpriced services.

Services ordered from external vendors through the hotel desk, such as car rental, can be from less reputable vendors that overcharge the customer or practice bait-and-switch.

Claims of damage

At check-in, you are required to provide a credit card, and you sign a contract that you can be held accountable for any damages. You do not think anything of this. It seems like routine procedure anywhere. But long after you check out, you find your card has been heftily billed by the hotel. You contact your credit card company to dispute this, but the hotel responds by sending the credit card company a picture of supposed damage, and a supposed bill from a contractor to repair it. This could easily be fictitiously produced with today's printers, but the credit card company accepts this as valid evidence, and sides with the hotel. You are stuck to pony up the charges, plus any interest that may have accrued during the dispute period.

Another variant is for the hotelier to accuse travellers of stealing towels or other small items; instead of making the accusation to the client's face, the charge is merely silently added to the credit card bill. When the traveller disputes it, the hotel backs off... only to try the same scam against subsequent travellers.

Disposal of possessions

You return to your motel for the final night of your stay, only to find the key will not work. You go to the office, and you've been informed you paid for one less night. You are also told the management cleaned out the room and disposed of your possessions you left behind. Management, in reality, has kept your possessions and is planning to sell those which are valuable, all while you are angry and helpless.

Early eviction

You have paid for a lengthy stay at a hotel, but before you have stayed many of those nights, management informs you that you are evicted for some minor offense that you did not know was wrong, did not expect to be enforced, or did not commit at all. But management is adamant and insists you must leave or you are trespassing. Management refuses to refund the remainder of your stay. It is their trick to obtain money from you without rendering services. Perhaps you may contact law enforcement about being refused the refund, but they cannot help. A remedy can be to pay one night at a time unless you know you're staying in a reputable hotel or if booked as part of a packaged deal from a reputable company.

Fake booking site

Online booking sites have become a common method of reserving hotels these days. Commonly known sites include hotels.com, Expedia, and CheapTickets.

But other lesser known sites will advertise the very same hotels, and upon making the reservation, will give you everything that appears normal, including a confirmation number, and will take your money. But upon arrival, the facility will tell you they do not have a reservation made by you, and they do not do business with such a company. Your reservation will not be honored, and your money is lost.

To prevent this, only book through the sites of reputable booking companies – or, better yet, contact the property directly before booking anything. Type the booking company's web address directly into the browser address bar rather than following a link from another site, where the link may direct to a nefarious website.

Common red flags are that you have never heard of the company before and prices lower than reputable booking companies for the same property that are too good to be true. Nonetheless, even major booking companies (which appear prominently in Internet search results) may abuse their position in subtle but harmful ways. Tripadvisor routinely removes a property's direct contact information from user-submitted reviews; a few innkeepers report Expedia displays a description of their property but reports no room in the inn or inability to determine whether any rooms are available when these rooms are indeed vacant. The booking sites, as middleman, bait-and-switch the voyager away from contacting the property directly or even switch the user away to some other hotel willing to pay them a commission or fee for referrals.

Another variant is the hidden middleman, where you think that you've contacted the hotel but you're actually talking to a reseller who is taking a commission for themselves. For instance, +1-800-HOLIDAY (465-4329) is a major hotel chain; +1-800-H0LIDAY (405-4329) is not the hotel chain but an unaffiliated reseller. The reservations created are real, either in the original hotel or a direct competitor, but dealing with a typosquatter instead of someone advertising for business by legit and conventional means might not get the best available rate as it's one more middleman to pay.

The middleman who goes broke after accepting payment but before paying the hotelier can also create a huge problem for the traveller. In one such incident, Canada's Conquest Vacations went bankrupt in 2009, effectively leaving its travellers in Mexican hotels physically held hostage by private security until they paid for the rooms again at a cost of thousands of dollars.

Home stay networks

The Internet has fueled massive growth in hospitality exchange and vacation rentals by allowing homeowners to list rooms or entire apartments for rent with relative ease. These can be an excellent money saver if used cautiously and honestly, but there are risks and pitfalls both for the voyager and the home owner.

The major sites make a token attempt to curb abuse by allowing users to rate their hosts (or their guests) and by handling payments through the platform's own website. These precautions can be circumvented using various schemes.

Scammers often steal login information of a legitimate user and change the profile to make it their own, giving the appearance of an established user with positive feedback. They then list a home for rent, responding to inquiries by directing users away from the original site onto a fake site (so their e-mails in response to your inquiry on airbnb.com send you to airbnb.some-bogus-domain.com, which looks official but contains bogus assurances that any bank transfer you send is "100% secure and protected"). If you make a payment outside the system provided by the real home stay site? Nothing's protected, the scammer has your cash and is gone. Good luck finding them if the entire transaction was carried out using someone else's stolen identity, right down to using a stolen payment card to pay to host the fake website.