Zuffenhausen

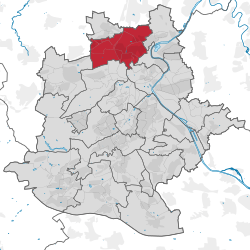

Zuffenhausen is one of three northernmost urban districts of the city of Stuttgart, capital of the German state of Baden-Württemberg. The district is primarily an incorporation of the formerly independent townships Zuffenhausen, Zazenhausen, Neuwirtshaus, and Rot, the latter is a historic town that gained importance in 1945 as a refugee camp for German refugees. As of 2009 around 35,000 people lived in Zuffenhausen's area of 1,200 ha (12 km2), making it the third largest of Stuttgart's outer urban districts. Zuffenhausen is also one of the oldest continuously inhabited places in Stuttgart with evidence of permanent settlements that can be traced back 7,500 years.

Zuffenhausen | |

|---|---|

Church of Saint Paul | |

Coat of arms | |

Location within Stuttgart  | |

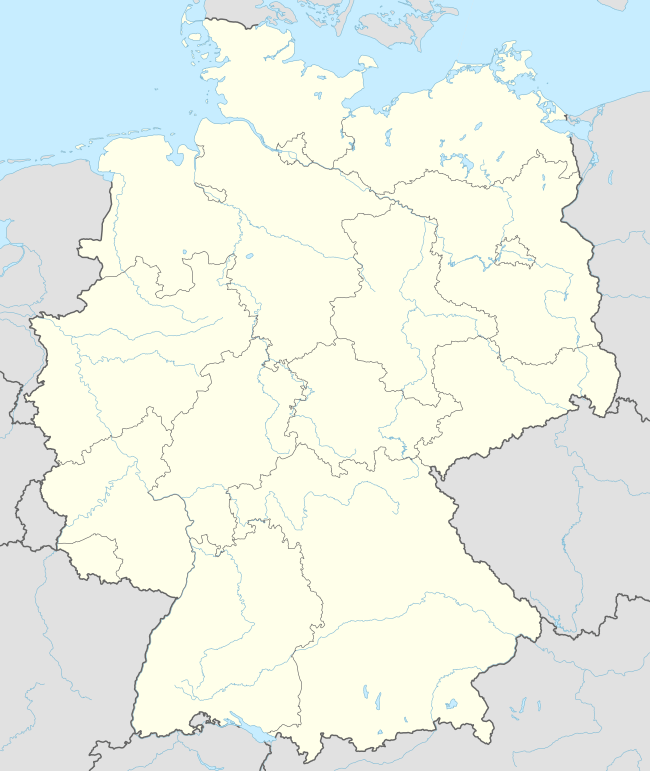

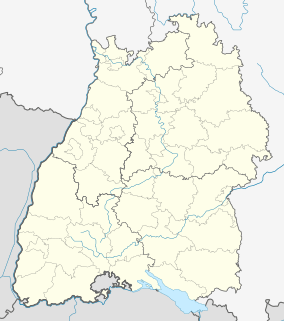

Zuffenhausen  Zuffenhausen | |

| Coordinates: 48°49′N 9°10′E | |

| Country | Germany |

| State | Baden-Württemberg |

| Admin. region | Stuttgart |

| District | Urban district |

| City | Stuttgart |

| Government | |

| • District Director | Gerhard Hanus[1] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 11.96 km2 (4.62 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 327 m (1,073 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 252 m (827 ft) |

| Population (2009-12-31) | |

| • Total | 35,568 |

| • Density | 3,000/km2 (7,700/sq mi) |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) |

| Postal codes | 70435, 70437, 70439 |

| Dialling codes | 0711 |

| Vehicle registration | S |

| Website | www.stuttgart.de |

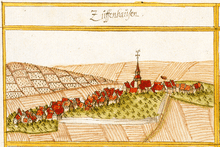

The etymological roots of "Zuffenhausen" are assumed to be found in the name of a seventh century Alemanni settler "Uffo" or "Offo". The oldest known official denotation as a property of Bebenhausen Abbey by Pope Innocent III dates to May 18, 1204. Zuffenhausen was proclaimed a city in 1907, yet soon financially badly affected by the Great Depression, Zuffenhausen and later Zazenhausen, agreed to the incorporation into Stuttgart city on 1 April 1931.

Stuttgart-Zuffenhausen station on the Franconia Railway is served by lines S4, S5, S6 and S60 of the Stuttgart S-Bahn. The headquarters of Porsche and the Porsche Museum are located in Zuffenhausen. Stuttgart Neuwirtshaus (Porscheplatz) station is nearby and served by lines S6 and S60.

Geography

Geography, Topography and Geology

Zuffenhausen's terrain, a river valley carved into existence by the Feuerbach river, has two distinct elevations: Zuffenhausen with an average of 255 m (837 ft) and Zazenhausen at 252 m (827 ft). To the north and northwest are the vast stretches of the Langes Feld rolling hills on a height of over 300 m (980 ft) that peak at (327 m (1,073 ft) near Neuwirtshaus, an area that constitutes the eastern Strohgäu, a rich farmland largely free of trees. To the south are the Stuttgart Mountains and the Neckar valley to the east, followed by the Schurwald mountains. Irregular ascents are characteristic for the Zuffenhausen region, of which Burgholzhof is the highest at 359 m (1,178 ft) above sea level.

Zuffenhausen's and the northern part of the Stuttgart Bay's topography are crucial for transport and settlement planning, as a central north-south axis of the city's most important transport hub (Pragsattel) has always traversed the area. On August 29, 1797 Johann Wolfgang von Goethe drove through Zuffenhausen on this road while on his third trip to Switzerland from Ludwigsburg.[2]

The location of settlements in the municipal area was determined by the quality of the soil, proximity to the river and the necessity to build high enough that the Feuerbach and its tributaries would not inundate the area in case of flooding, yet to be close enough to a water source and the major trade routes.[3]

Geology

The geology of Zuffenhausen is, by the nature of a cuesta landscape, determined by a topographically varied picture of the different layers of rock and sediment as they were deposited in the 240 to 145 million year span of time that Zuffenhausen was part of the bottom of a tropical ocean. This is manifested in the presence of countless quarries and the many fossil discoveries from a layer of Muschelkalk at the bottom of this formation, that surfaces on several locations. On top are layers of Lettenkeuper and Gipskeuper that indicate the area's height around sea level at the time of the Triassic period.[4] Following that is the Schilfsandstein; sediment deposited here, that originates from an old river delta of an ancient river system, of which the only remains are to be found on the highest areas of the Burgholzhof and the Lemberg. Higher layers are not expected to be found in the area due to the relatively low elevation and only occur in relation to local faultlines.

Zuffenhausen area is traversed by a huge faultline, called the "Schwieberdinger-Zuffenhäuser-Cannstatter rejection", which was formed 65 million years ago by the tectonic activities that created the nearby Alps. It has a fault height of about 110 m (360 ft), from which rise the mineral waters of nearby Cannstatt. In Zuffenhausen it led to the fact that, due to its irregular course, greatly disturbed by collapses of quarries, Muschelkalk and Gipskeuper alternately surfaced at about the same height and further to the west near Neuwirtshaus even elements of ragstone and the Löwenstein Formation.

Landscape, flora, and fauna

Landscape development:[5] The diverse landscape present in Zuffenhausen is the result of a disparate geological history the deposited various soils and rocks of differing density and solubility. The ice ages of the Pleistocene era completed the recent physiography, composed largely of Loess, Brown and Black soils, the prerequisites for later agricultural use, that began during the Neolithic Revolution with the Linear Pottery culture. Though these fertile soils were spread generously across the river valley, some areas were less fertile than others and were thus better suited for pastures. In the succeeding Holocene epoch, the landscape changed from Tundra into Deciduous forest, whose composition changed several times parallel to climate fluctuations. The Linear Pottery culture, established since the mid 6th Millennium BC started to slowly turn the area into a Cultural landscape around central settlements that featured patterns of pastures and fields for agriculture, as hunting accounted for only 10% of meat consumption.[5]

These settlements must be imagined as increasingly large settlement chambers enclosed in forest, which at that time covered Middle-Europe. Still, the forest remained economically irreplaceable for a long time by means of forest grazing, logging and gathering of fruit, as pastures and meadows in the present sense did not yet exist. However, especially in the Loess areas, the forests quickly faded by intensive use within decades and their composition also changed with Elm and Tilia disappearing almost completely. However, the settlements continued to be islands in a sea of forest.

Loosely wooded forests existed as far back as the 18th century, such as lush oak forests of the Burgholzhof, which were used for pig farming, and as pointed out by names such as Wannenwald, Kögelwald and Lorcher Mönchswald. The Lembergwald also stretched farther east than now and was a ducal hunting forest, which must have been so profitable that it was worthwhile to erect a hunting castle on the Schlotwiese. Today there are only a larger connected forest area in Zuffenhausen, namely on the Lviv, (a translation of Lemberg by Google Translate) a mountain range rising from east to west with the Feuerbach vineyards on the south side and the wooded northern slope on the north side of the Zuffenhausen side. However, pieces of that primordial forest still exist as the "Hofkammerwald" (named after the man who once owned the land), an area of over 58 hectares (0.58 km2) that has been operated by the City of Stuttgart as a community forest since 1968. The eastern part of the forest is the present city park, the northern section near Neuwirtshaus is now Schützenwies Forest, the westernmost part in Weilimdorf is now called the Maierwald.[6]

The modern course and the valley marshes of the Feuerbach exist since the Holocene, which created large deposits of fine material during high tides of up to 8 m (26 ft) as the one near the old village, nicknamed the Alte Flecken (German: old stain, or old spot). In modern times, the entire water network is oriented on the Neckar, but the Feuerbach is still an important part of it featuring several tributaries of its own coming mostly from the west. The old town center was hardly affected by floods because of its location on the elevated west bank. A few old creeks and streams would later become city streets. The water network depended on the density and composition of the bedrock as Muschelkalk with its many crevices permits percolation that causes superficial outflows.

Since the 19th century, people have also considerably changed the geographical features of Zuffenhausen via the development of railway lines and roads, the excavated material was used to fill depressions and drain local ponds. Until very recently, the settlement of Zuffenhausen itself was confined to the valley created by the Feuerbach eons ago. The landscape changed during the massive expansion of settlements beyond the Feuerbach valley, especially during the second half of the 19th century to the west and to the east, after 1945, with the introduction of Sealed roads and the rerouting of streams in unprecedented scale. Further profound changes on the landscape took place after the Second World War as agricultural lands were leveled with debris and overburden. Miscellaneous changes to the landscape includes the filling in of a few old quarries and clay pits in the Feuerbach river valley, and the creation of a high plateau of an old ditch that came down from Stammheim, which now serves as an expansion of Zuffenhausen's cemetery.

The flora and fauna are quite diverse, even though the fauna have declined in number since the introduction of sealed roads.[7] Birds, however, are less affected by the loss of habitat thanks to generously sized home gardens and the Hofkammerwald. Located west of Zuffenhausen are larger forests and different types of semi-arid grassland between increasingly marginal fields and by now almost totally absent pastures and orchards, that were the most important assets of Zuffenhausen's economy until 1907, still visible on the Coat of Arms of Zazenhausen. Since the emergence of a concern for the conservation of natural habitats and the creation of an association for local biospheres in 2003, nature reserves have been declared as conservation areas by the local government. Most of the vineyards on the western slope of the Feuerbach river in the region were made fully operational between 1976 and 1979.

Environmental protection:[8] In response to prolonged pollution with nitrogen oxide and particulates from the relatively heavy traffic nearby that caused forest damage and the ongoing disruptions of the formation of the water table a comprehensive environmental protection program has been established.[9] Noise pollution in the area is attributed to the Bundesautobahn 81, Bundesstraße 10, 27, 27a, the Stuttgart S-Bahn and the Stuttgarter Straßenbahnen. Measures have been made to improve the situation faced by the landscape of Zuffenhausen, such as land restoration, the creation of wildlife corridors, and the establishment of green development plans.

History

Overview

Stuttgart-Zuffenhausen has been consistently inhabited for about 7500 years. Paleo-Humans, such as Neanderthals and Homo erectus have stalked the rich and abundant wildlife present for roughly 300,000 years, as evidenced by the discovery of early tools typically made of mammoth bones at Travertine quarries in nearby Cannstatt and Ludwigsburg.

During the Middle Ages, Zuffenhausen was often mistakenly referred to as "Offenhausen" and "Ottohausen" due to differences in Alemannic German and later German tongues. For most of its history, Zuffenhausen has served as valuable farmland for its owners. On April 23, 1907, during the reign of King William II of Württemberg, Zuffenhausen became a city and would later be incorporated into Stuttgart on March 31, 1931, following financial difficulties symptomatic of the Great Depression.[10] The convenient location of Zuffenhausen on the bank of the Neckar River led to a sharp incline in population during the Industrial Revolution, when the purely rural character of Zuffenhausen was finally phased out.[10]

On May 1, 1933 Zazenhausen, Neuwirtshaus, and Zuffenhausen were united in one district. Starting in 1949, Zuffenhausen became increasingly important to Stuttgart as an industrial district. The "Rotwegsiedlung", called the SS siedlung had already been founded in 1938. In the course of the plans for re-division of 1956, all administration in Stuttgart was completely restructured.

Since January 1, 2001, after yet another administrative reorganization of the municipalities of Stuttgart, Zuffenhausen is endowed with 11 municipalities. Zuffenhausen remains an important local and international industrial center, as the locality of the headquarter of Porsche automobiles.[10]

Prehistory and Early History

The prehistoric finds made in Zuffenhausen district and surrounding areas (Lemburg, Burgholzhof, Stammheim, and Viesenhäuser Hof) date back to the Neolithic and rank among some of the oldest and most diverse of the Urban districts of Stuttgart. Though many settlements from the Neolithic to the Iron Age have existed, Zuffenhausen entered the era of recorded history during the period of the Alemanni tribes.

Paleolithic and Mesolithic Zuffenhausen

Paleolithic:[11] Numerous findings and excavations in the area suggest the usage of hills in the region as paleolithic rest stops as far back as the Middle Paleolithic (300,000 years ago), suggesting that early peoples came through the region frequently. Further substantiation is corroborated by tools and processed bones discovered at travertine quarries in nearby Bad Cannstatt.[12][13]

The first finds made in Zuffenhausen itself originate only from the Upper Paleolithic. In 1879, four hand scrapers and pieces of flint and mammoth bone pieces were discovered at Hofäcker brickyard. Whether they can be attributed to Neanderthals or early modern humans is unknown. At this time, Europe's landscape was glacial tundra, where ancient hunter gatherer societies followed and hunted the large herds of Mammoths, Reindeer, and Wild horses that migrated around ancient Stuttgart.

Mesolithic:[14] Initially, humans living here during the Mesolithic era were nomadic. Several tool storage pits dating back to the Mesolithic period have been discovered in the Stuttgart area, primarily in Bad Cannstatt and Burgholzhof in the Zuffenhausen district, that contained microliths, characteristic for the Mesolithic.

Neolithic Zuffenhausen

Early Neolithic (Linear Pottery):[15] The primary discoveries dating back to this period include the remains of a settlement with its iconic banded ceramics in the northern and eastern areas of the district. Such settlements developed at the southern edge of the Long Field, where good loess was available. Since crop rotation was a yet unknown practice, early settlements and their residents had to practice Shifting cultivation (as evidenced by the aforementioned Linear Pottery culture) as the nutrients in the soil became depleted. Even with the practice of shifting cultivation, archaeological evidence shows that dimensions of the fields and the settlements were too large. After about three years of use, the field would deplete and require decades to regain the lost fertility (longhouses typically would stand for about 30 to 50 years).[16][17] Due to the existence of such types of soils it is implied that there used to be a warmer climate and open wooded steppes during the Holocene period that were suitable for clearing and could be found in valleys. A few "Stool tombs" from this period have been discovered in hollow ditches, complete with grave goods. One of these graves contained one of the oldest examples of prepared food (legumes, toasted bread, hazelnuts and flaxseed), which was intended likely for provision in the afterlife journey and allow conclusions regarding their religious ideas which probably included ancestor worship. They cultivated einkorn, emmer and wheat, but only after the cutting down and incineration of nearby mixed oak forests by early settlements in need of new lands for crops.

As is common knowledge, the Neolithic Revolution saw the birth of civilization and Zuffenhausen was no different. As the longhouses on the various farmsteads that would soon become small farming villages began to stand at a length of about 40 feet (12 m), man began to keep domesticated sheep, pigs, and goats. The remains of several of these early sites have been discovered in the Zuffenhausen area from many different phases of the Early Neolithic period. The largest of these sites, located in Rot, yielded many individual finds of flint tools (blades, scrapers, axes, Quern-stones) and even inkstones and ceramics. The large amount of flint tools, blades in particular, suggests that the production of the tools using techniques such as stone grinding had become traditional. Such findings are spread across the region between Neuwirtshaus, Friedrichswahl, Zazenhausen and Rot and even beyond the Feuerbach river valley. The site of the old town center was an unsuitable location for the longhouses of the Linear Pottery culture (usually about 20 to 40 m (66 to 131 ft) long, typically held up to 60 persons and their cattle) as it was a swampy floodplain (the average temperatures of the climate were about 2 to 3 degrees higher than they are now), so they built their villages (typically a cluster of 10 or so buildings) at more elevated locations that still had a decent amount of loess.[18][19] Another notable series of local discoveries are the about 200 tombs belonging to the Bandkeramik peoples in the 6th millennium BC have been unearthed. These findings, when combined with the roughly 4000 traces of prehistoric settlement like Hallstatt houses would indicate that this area was a favorite haunt of early civilization.[20]

Middle Neolithic:[21] Starting at the end of the 6th Millennium BC, the decoration on the pottery changed, stone axes began to actually have holes for the handle instead of the usage of glue or a splice. The dead were no longer buried in fetal position but instead lying on their backs as is the modern custom. In Southern Germany, the Mesolithic cultures at that point present were replaced by the Hinkelstein culture, the Großgartacher culture, the Planig-Friedberg culture, and the Rössen culture. These groups made little to no record of their existence in Zuffenhausen but a site belonging to the Großgartach culture was discovered in the district near Mühlhausen village.[22]

The Neolithic Age of south-western Germany begins with the Schwieberdinger culture that had developed into a distinct regional style during the 5th Millennium BC and was followed by the Schussenrieder culture.[21]

Late Neolithic, Chalcolithic:[23] Though hardly evident in Zuffenhausen, the usage and creation of copper tools by the Goldberg III culture and the Horgen culture with the earliest wheel discoveries had become widespread in Upper Swabia by the mid-4th Millennium BC. Settlers of the Beaker culture, another mid-4th Millennium culture in Neolithic Europe, left behind multiple examples of their typical pottery, flat graves and jewelry in a region stretching from Zuffenhausen to Kornwestheim. Other notable early Bronze Age items in the Zuffenhausen area are various pottery caches attributed to the Corded ware culture.

| Bronze Age |

| ↑ Chalcolithic |

|

Africa, Near East (c. 3300–1200 BC)

Indian subcontinent (c. 3300–1200 BC) Europe (c. 3200–600 BC)

East Asia (c. 3100–300 BC) |

|

| ↓Iron Age |

Bronze Age Zuffenhausen

Next to no barrows from the Bronze Age can be found in the area of Zuffenhausen, even though barrows from the Iron Age Hallstatt culture and later times are present. However, in nearby Ludwigsburg and Weilimdorf, Bronze Age barrows do exist, although the smaller tombs were all destroyed by farming and irrigation.

Artifacts of the Urnfield people were excavated at the Hohlgraben, Friedrichshaller Street in Zuffenhausen itself and in Neuwirtshaus, such as ceramics, bronze brooches and Rainbow cups, which are the only demonstrable pieces of evidence for the settlement of Zuffenhausen during the Bronze Age.[24]

Pre-Roman Iron Age Zuffenhausen

Inside the city district of Zuffenhausen, six hills inside Schelmenwasen city park have been identified as grave mounds. They stand at about 0.3 to 2 m (0.98 to 6.56 ft), above ground and have a diameter of 15 to 33 m (49 to 108 ft). Unfortunately, when the mounds were opened, they only wielded bone fragments and a few minor artifacts. Outside the city, another nine burial mounds have been identified, that seem to suggest a relationship to the late Hallstatt settlements of South-Stammheim, where waste pits and a storage cellars were found. Similarly such findings were made in Rot (a foot shackle made of bronze) and in Neuwirtshaus . By far the largest discovery in the region is a massive Iron Age fortification with several walls that occupied an area of about 6,000 m2 (65,000 sq ft).

Roman Zuffenhausen

The sparsely inhabited land north of the Danube river and east of the Rhine river that Roman geographer Claudius Ptolemy called the "Helvetii Wastelands" came under Roman administration in the late 1st century CE. Gradually, border fortresses and the Rhaetian Limes as well as towns and cities were established. Increasingly documented by written sources, a Roman provincial culture emerged in this Agri Decumates of Germania Superior with Mainz (then known as Mogontiacum) as the region's capital and seat of the governor. From 85 to 90 CE, one of the most important Roman forts north of the Alps was built on the Altenburg near Bad Cannstatt. This fortress, now known as Castrum Stuttgart Bad Cannstatt, spanned about 37,400 m2 (403,000 sq ft), housed 500 horsemen, and had about 20 towers. Civilian estates (mostly Villa rustica), while being nowhere near as gigantic as the Castrum, were still numerous throughout the region and existed to supply the plebeian soldiers and patrician officers alike. In Baden-Württemberg alone, at least a thousand such estates are known to exist and the majority thereof in the fertile Neckar river valley around Zuffenhausen, Bad Cannstatt, Ludwigsburg, and Heilbronn. With the Romans came horticulture, the vineyards that still blanket the hills around Stuttgart, the orchards, Roman roads, factory produced pottery (Terra sigillata), and culture of the Romans.[26] Overall, Roman archeological sites inside Stuttgart are extremely numerous.[20]

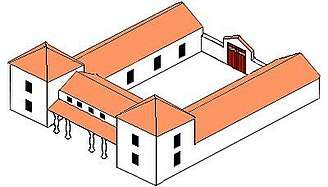

The area of Zuffenhausen contains numerous of these cultural testimonies, such as several estates spread across the south and southeastern parts of the river valley that made intensive use of the soil (regardless of its fertility), as the need for food was enormous and required an extensive road network. One of the main southwestern Roman roads in Germany, marked by Roman milestones, started at Mainz (Mogontiacum) and passed through Schwieberdingen, up the alps and finally to Heidenheim an der Brenz. Even 2,000 years later, this rectilinear route to Schwieberdingen is nearly identical to its modern counterpart. In Neuwirtshaus, a waystation where travelers could exchange their horses for fresh mounts existed on this highway.

By about 232/233 AD, Germanic peoples (the Alemanni especially) began to cause the destruction of the Empire from within and without. The cracks started showing in earnest when the Alemanni overran Agri Decumates in 260 and the wars of 353 to 378 AD (thus bringing Old High German into the region). Later, the Alemanni would also expand into Alsace before being conquered by Clovis and the Franks. As Roman central leadership slowly withered and died with the rest of the Empire, the Romans left the region to its own devices. When the Alemanni became the new masters of the region, they began to organize it into territories.[27]

Alemanni and Merovingian Zuffenhausen

With the Romans left written documents become sparse and knowledge of Zuffenhausen's history during the Migration Period is obtained by archaeological excavations.

In the so-called "Expansion Phase" of the 7th century the Alemanni experienced the introduction of Christianity and a small explosion of population under strong Franconian-Merovingian influence. Places using the suffixes -hausen and -hofen developed in the region, especially in the north, such as Zuffenhausen, Zazenhausen, Mühlhausen, Viesenhausen and Hofen. Without a doubt, the Alemanni period in Zuffenhusen's history was the most influential for the layout of the town and its municipalities.

Zuffenhausen's beginnings:[28] The plot of land that made up Zuffenhausen at the time had a size of about 10 km2 (3.9 sq mi) and was determined by landmarks like the Burgholzhof (now part of Bad Cannstatt), the Lemberg, Roman roads and old burial mounds. Initially, it is assumed that in 600 CE the settlement consisted of two estates - the first by the old Roman road near a large cemetery and the other on the site of a previous Pre-Roman settlement (likely built to protect an east-west river crossing) as marked by the existence of large Alemanni burial mounds which yielded rich caches of artifacts. By the mid-7th century, these two settlements were joined, thus creating early Zuffenhausen.

Middle Ages

Twin towns

Trivia

- "Zuffenhausen" is also a kennel name used by UK Dobermann enthusiasts.[29]

References

Notes

- Gerhard Hanus Bio

- "von Goethe's Journal: August, 1797". zeno.org. Zeno.org.

- Gühring/Kull, p. 19

- Gühring/Kull, pp. 19–28

- Gühring/Kull, pp. 28–32

- Gühring/Kull, pp. 181–193

- Gühring/Kull, pp. 32–36

- Gühring/Kull p. 36

- Gühring/Kull, p. 36

- Official Site

- Gühring/Kull, p. 41

- Müller-Beck, pp. 252, 257–260

- Schukraft, p. 12

- Gühring/Kull, p. 42

- Gühring, pp. 42–44

- Keefer, pp. 90–107

- Müller-Beck, p. 464

- Keefer, p. 90, 106

- Hoffmann, p. 236

- Schukraft, p. 14

- Gühring/Kull, p. 45

- Keefer, p. 126–139, 145

- Gühring/Kull, p. 46

- Gühring/Kull, p. 47

- Gühring/Kull, p. 48

- Waßner, p. 24

- Gühring/Kull, p. 52

- Gühring/Kull, p. 55

- Archive: Dobermann

Bibliography

- Bassler, Siegfried (1987). Mit uns für die Freiheit. 100 Jahre SPD in Stuttgart. Stuttgart: Thienemanns Verlag. ISBN 3-522-62570-6.

- Bedürftig, Freidemann (1997). Lexikon Drittes Reich. 2. Munich: Piper. ISBN 3-492-22369-9.

- Benz, Wolfgang; Graml, Hermann; Weiß, Hermann (2001). Enzyklopädie des Nationalsozialismus. Munich: dtv. ISBN 3-423-33007-4.

- Brockhaus Enzyklopädie (19 ed.). Mannheim: FA Brockhaus. 1994. ISBN 3-7653-1200-2. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Broszat, Martin; Frei, Norbert (1996). Das Dritte Reich im Überblick. Chronik – Ereignisse – Zusammenhänge. 5. Munich: Piper. ISBN 3-492-21091-0.

- Cunliffe, Barry (1996). Illustrierte Vor- und Frühgeschichte Europas. Frankfurt am Main: Campus Verlag. ISBN 3-593-35562-0.

- Chronik der Deutschen. 4. Gütersloh: Chronik Verlag. 1995. ISBN 3-577-14341-X.

- Chronik des 20. Jahrhunderts. 14. Chronik Verlag/Weltbild Verlag. 1996. ISBN 3-86047-130-9.

- "Auszug aus der Geschichte". Der Große Ploetz. Freiburg: Verlag Ploetz. 1981. ISBN 3-87640-170-4.

- Fritz, Eberhard (1980). Arbeit gegen das Dritte Reich. Berlin: Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Berlin.

- Fiedler, Lutz; Rosendahl, Gaëlle; Rosendahl, Wilifried (2011). Altsteinzeit von A bis Z. Darmstadt: WBG. ISBN 978-3-534-23050-1.

- Gühring, Albrecht; Beer, Mathias; Binder, Petra; Ehmer, Hermann; Friederich, Susanne; Glück, Manfred; Heinz, Reinhard; Juréwitz, Peter; Kull, Ulrich; Meyle, Wolfgang; Müller, Roland; Raberg, Frank; Rees, Werner; W., Hermann (2004). Zuffenhausen. Dorf – Stadt – Stadtbezirk. Zuffenhausen: Verein zur Förderung der Heimat- und Partnerschaftspflege sowie der Jugend- und Altenhilfe. ISBN 3-00-013395-X.

- Gutman, Israel; Jäckel, Eberhard; Longerich, Peter; Schoeps, Julius (1998). Enzyklopädie des Holocaust. Die Verfolgung und Ermordung der europäischen Juden. 2. Munich: Piper. ISBN 3-492-22700-7.

- Hirsch, Rudolf; Schuder, Rosemarie (1999). Der gelbe Fleck. Wurzeln und Wirkungen des Judenhasses in der deutschen Geschichte. Wiesbaden/Cologne: Fourier/PapyRossa-Verlag. ISBN 3-932412-86-9.

- Hoffmann, Emil (1999). Lexikon der Steinzeit. Munich: Verlag C. H. Beck. ISBN 3-406-42125-3.

- Hansjörg, Kammerer (2004). Amtsenthoben. Maßnahmen gegen württembergische Pfarrer unter dem Regiment Deutscher Christen im Herbst 1934. Stuttgart: Verein für württembergische Kirchengeschichte. ISBN 3-7722-3044-X.

- Keefer, Erwin (1993). Steinzeit. 1. Stuttgart: Theiss Verlag. ISBN 3-8062-1106-X.

- Kühnl, Reinhard (2000). Der deutsche Faschismus in Quellen und Dokumenten. Wiesbaden/Munich: PapyRossa/Fourier. ISBN 3-932412-85-0.

- Lamb, Hubert (1994). Klima und Kulturgeschichte. Der Einfluss des Wetters auf den Gang der Geschichte. Reinbek: Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag. ISBN 3-499-55478-X.

- Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg (Hrsg.): Taschenbuch Baden-Württemberg. Gesetze – Daten – Analysen. Kohlhammer Verlag. 1984. ISBN 3-17-008226-4.

- Lüning, Jens; Stelhi, Petar (1989). Die Bandkeramik in Mitteleuropa: von der Natur- zur Kulturlandschaft. Spektrum der Wissenschaft (Hrsg.): Siedlungen der Steinzeit. Heidelberg: Die Bandkeramik in Mitteleuropa: von der Natur- zur Kulturlandschaft. pp. 110–120. ISBN 3-922508-48-0.

- Mann, Golo (1986). Propyläen Weltgeschichte. Eine Universalgeschichte. Berlin, Ullstein, Frankfurt: Propyläen Verlag. ISBN 3-549-05731-8.

- Miller, Susanne; Potthof, Heinrich (1983). Kleine Geschichte der SPD. Darstellung und Dokumentation 1848–1983. 5. Bonn: Verlag Neue Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-87831-350-0.

- Mirow, Jürgen (1996). Geschichte des deutschen Volkes. Von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart. 2. Gernsbach: Casimir Katz Verlag. ISBN 3-925825-64-9.

- Müller-Beck, Hansjürgen (1983). Urgeschichte in Baden-Württemberg. Stuttgart: Konrad Theiss Verlag. ISBN 3-8062-0217-6.

- Schukraft, Harald (1999). Wie Stuttgart wurde, was es ist. Ein kleiner Gang durch die Stadtgeschichte. Stuttgart: Silberburg Verlag. ISBN 3-87407-222-3.

- 111 Jahre SPD Zuffenhausen 1889–2000. Sozialdemokratische Geschichte am Beispiel eines Stuttgarter Ortsvereins. Zuffenhausen: SPD-Ortsverein. 2000.

- Licht auf dunkle Zeit. Stuttgart in der Zeit von 1933 bis 1945. Stuttgart: Stadtjugendring Stuttgart. 2000.

- "Zuffenhausen". Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago. 1993.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stuttgart-Zuffenhausen. |

- Official site

- City site

- Porsche in Zuffenhausen

- "Zuffenhausen" (PDF) (in German). Statistisches Amt Stuttgart. 2009. Retrieved 2011-10-08.