Zoraptera

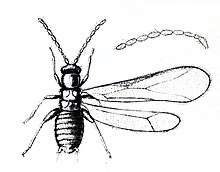

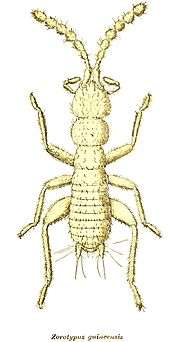

The insect order Zoraptera, commonly known as angel insects, contains a single family, the Zorotypidae, which in turn contains one extant genus Zorotypus with 44 extant species and 11 species known from fossils. They are small and soft bodied insects with two forms: winged with wings sheddable as in termites, dark and with eyes (compound) and ocelli (simple); or wingless, pale and without eyes or ocelli. They have a characteristic nine-segmented beaded (moniliform) antenna. They have mouthparts adapted for chewing and are mostly found under bark, in dry wood or in leaf litter.[1]

| Zoraptera | |

|---|---|

| |

| Female of winged form with antenna of male | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | Zoraptera Silvestri, 1913 |

| Family: | Zorotypidae Silvestri, 1913 |

| Genus: | Zorotypus Silvestri, 1913 |

| Species | |

|

See text | |

Description

The name Zoraptera, given by Filippo Silvestri in 1913,[2] is misnamed and potentially misleading: "zor" is Greek for pure and "aptera" means wingless. "Pure wingless" clearly does not fit the winged alate forms, which were discovered several years after the wingless forms had been described.

The members of this order are small insects, 3 millimetres (0.12 in) or less in length, that resemble termites in appearance and in their gregarious behavior. They are short and swollen in appearance. They belong to the hemimetabolous insects. They possess mandibulated biting mouthparts, short cerci (usually 1 segment only), and short antennae with 9 segments. The abdomen is segmented in 11 sections.[3] The maxillary palps have five segments, labial palps three, in both the most distal segment is enlarged. Immature nymphs resemble small adults. Each species shows polymorphism. Most individuals are the apterous form or "morph", with no wings, no eyes, and no or little pigmentation. A few females and even fewer males are in the alate form with relatively large membranous wings that can be shed at a basal fracture line. Alates also have compound eyes and ocelli, and more pigmentation. This polymorphism can be observed already as two forms of nymphs. Wingspan can be up to 7 millimetres (0.28 in), and the wings can be shed spontaneously. When observed, wings have simple venation.[3] Under good conditions the blind and wingless form predominates, but if their surroundings become too tough, they produce offspring which develop into winged adults with eyes. The wings are paddle shaped, and have reduced venation.

Phylogeny

The phylogenetic relationship of the order remains controversial and elusive. At present the best supported position based on morphological traits recognizes the Zoraptera as polyneopterous insects related to the webspinners of the order Embioptera. However, molecular analysis of 18s ribosomal DNA supports a close relationship with the superorder Dictyoptera.[4][5][6][7][8]

Behavior and ecology

Zorapterans live in small colonies beneath rotting wood, lacking in mouthparts able to tunnel into wood, but feeding on fungal spores and detritus. These insects can also hunt smaller arthropods like mites and collembolans.[9]

Zorotypus gurneyi lives in colonies consisting of up to several hundred of individuals. Most commonly the colonies have a size of around 30 individuals, of which about 30% are nymphs, the remainder adults. Zoraptera spend most of their time grooming one another. The grooming process is thought to be a way of removing fungal pathogens.[10]

When two colonies of Z. hubbardi are brought together experimentally, there is no difference in behavior towards members of the own or new colony. Therefore, colonies in the wild might merge easily. Winged forms are rare. The males in such average colonies establish a linear dominance hierarchy in which age or duration of colony membership is the prime factor determining dominance. Males appearing later in colonies are at the bottom of the hierarchical ladder, regardless of their body size. By continually attacking other males, the dominant male monopolizes a harem of females. The members of this harem stay clumped together. There is a high correlation between rank and reproductive success of the males.[11][12]

Z. barberi lack such a dominance structure but display complex courtship behavior including nuptial feeding. The males possess a cephalic gland that opens in the middle of their head. During courtship they secrete a fluid from this gland and offer it to the female. Acceptance of this droplet by the female acts as behavioral releaser and immediately leads to copulation.[9]

In Z. impolitus, copulation does not occur, but fertilization is accomplished instead by transfer of a spermatophore from the male to the female. This 0.1-millimetre (0.0039 in) spermatophore contains a single giant sperm cell, which unravels to about the same length as the female herself, 3 millimetres (0.12 in). It is thought that this large sperm cell prevents fertilization by other males, by physically blocking the female's genital tract.[13][14]

Effects on ecosystem

Zoraptera are thought to provide some important services to ecosystems. By consuming detritus, such as dead arthropods, they assist in decomposition and nutrient cycling.[15]

Species

55 living and fossil species are found worldwide, mainly in tropical and subtropical regions around the world. Four species occur north of the Tropic of Cancer, two in the United States and two in Tibet.

There are 44 extant and 11 extinct species known as of 2017, many of the fossil species are known from Burmese amber.[16][17]

- †Zorotypus absonus Engel 2008 - Dominican Republic (Miocene) (fossil)

- †Zorotypus acanthothorax Engel & Grimaldi 2002 - Myanmar (Cretaceous) (fossil)

- Zorotypus amazonensis Rafael & Engel 2006 - Brazil (Amazonas)

- Zorotypus asymmetricus Kocarek 2017 - Brunei

- Zorotypus asymmetristernum Mashimo 2018 - Kenya

- Zorotypus barberi Gurney 1938 - Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, French Guiana, Panama, Trinidad and Tobago, Venezuela

- Zorotypus brasiliensis Silvestri 1947 - Brazil (Minas Gerais, Parana, Rio de Janeiro, Santa Catarina, São Paulo)

- Zorotypus buxtoni Karny 1932 - Samoa

- Zorotypus caudelli Karny 1922 - Indonesia (Sumatra), Malaysia (peninsular)

- Zorotypus caxiuana Rafael, Godoi & Engel 2008 - Brazil (Para)

- †Zorotypus cenomanianus Yin, Cai & Huang 2017 - Myanmar (Cretaceous) (fossil)

- Zorotypus cervicornis Mashimo, Yoshizawa & Engel 2013 - Malaysia (peninsular)

- Zorotypus ceylonicus Silvestri 1913 - Sri Lanka

- Zorotypus congensis van Ryn-Tournel 1971 - Congo (Dem.Rep.)

- Zorotypus cramptoni Gurney 1938 - Guatemala

- †Zorotypus cretatus Engel & Grimaldi 2002 - Myanmar (Cretaceous)

- Zorotypus delamarei Paulian 1949 - Madagascar

- †Zorotypus denticulatus Yin, Cai & Huang 2017 - Myanmar (Cretaceous) (fossil)

- †Zorotypus goeleti Engel & Grimaldi 2000 - Dominican Republic (Miocene)

- Zorotypus guineensis Silvestri 1913 - Ghana, Guinea, Ivory Coast

- Zorotypus gurneyi Choe 1989 - Costa Rica, Panama

- Zorotypus hainanensis Yin & Li 2015 - China (Hainan Island)

- Zorotypus hamiltoni New 1978 - Colombia

- Zorotypus huangi Yin & Li 2017 - China (Yunnan)

- Zorotypus hubbardi Caudell 1918 - United States (mainland)

- †Zorotypus hudae (Kaddumi 2005) - Jordan (Cretaceous)

- Zorotypus huxleyi Bolivar y Pieltain & Coronado 1963 - Brazil (Amazonas), Peru

- Zorotypus impolitus Mashimo, Engel, Dallai, Beutel & Machida 2013 - Malaysia (peninsular)

- Zorotypus javanicus Silvestri 1913 - Indonesia (Java)

- Zorotypus juninensis Engel 2000 - Peru

- Zorotypus lawrencei New 1995 - Christmas Island

- Zorotypus leleupi Weidner 1976 - Ecuador (Galapagos Islands)

- Zorotypus longicercatus Caudell 1927 - Jamaica

- Zorotypus magnicaudelli Mashimo, Engel, Dallai, Beutel & Machida 2013 - Malaysia (peninsular)

- Zorotypus manni Caudell 1923 - Bolivia, Peru

- Zorotypus medoensis Huang 1978 - China (Xizang)

- Zorotypus mexicanus Bolivar y Pieltain 1940 - Mexico

- †Zorotypus mnemosyne Engel 2008 - Dominican Republic (Miocene)

- †Zorotypus nascimbenei Engel & Grimaldi 2002 - Myanmar (Cretaceous)

- Zorotypus neotropicus Silvestri 1916 - Costa Rica

- Zorotypus newi Chao & Chen 2000 - Taiwan

- Zorotypus novobritannicus Terry & Whiting 2012 - Papua New Guinea (New Britain)

- † Zorotypus oligophleps Liu, Zhang, Cai & Li, 2018

- †Zorotypus palaeus Poinar 1988 - Dominican Republic (Eocene)

- Zorotypus philippinensis Gurney 1938 - Philippines

- † Zorotypus robustus Liu, Zhang, Cai & Li, 2018

- Zorotypus sechellensis Zompro 2005 - Seychelles

- Zorotypus shannoni Gurney 1938 - Brazil (Amazonas, Mato Grosso)

- Zorotypus silvestrii Karny 1927 - Indonesia (Mentawai Islands)

- Zorotypus sinensis Huang 1974 - China (Xizang)

- Zorotypus snyderi Caudell 1920 - Jamaica, United States (Florida)

- Zorotypus swezeyi Caudell 1922 - United States (Hawaii)

- Zorotypus vinsoni Paulian 1951 - Mauritius

- Zorotypus weidneri New 1978 - Brazil (Amazonas)

- Zorotypus weiweii Wang, Li & Cai 2015 - Malaysia (Sabah)

- Zorotypus zimmermani Gurney 1939 - Fiji

- †Xenozorotypus burmiticus Engel & Grimaldi 2002 - Myanmar (Cretaceous)

Uses

Zoraptera are also used in the production of amber jewelry.[18]

References

- Rafael, JA; Godoi, FDP; Engel, MS (2008). "A new species of Zorotypus from eastern Amazonia, Brazil (Zoraptera: Zorotypidae)". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 111 (3 &, 4): 193–202. doi:10.1660/0022-8443-111.3.193.

- Silvestri, F (1913). "Descrizione di un nuovo ordine di insetti". Bol. Lab. Zool. Gen. Agric. Portici. 7: 193–209.

- Gullan; Granston (2005). The Insects: An Outline of Entomology.

- Yoshizawa (2007). "The Zoraptera problem: evidence for Zoraptera + Embiodea from the wing base" (PDF). Systematic Entomology. 32 (2): 197–204. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3113.2007.00379.x. hdl:2115/33766.

- Yoshizawa, K; Johnson, KP (2005). "Aligned 18S for Zoraptera (Insecta): Phylogenetic position and molecular evolution". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 37 (2): 572–580. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.05.008. hdl:2115/43133. PMID 16005647.

- Engel, MS; Grimaldi, DA (2002). "The first mesozoic Zoraptera (Insecta)". American Museum Novitates. 3362: 1–20. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.571.3443. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2002)362<0001:tfmzi>2.0.co;2.

- Ishiwata, K; Sasaki, G; Ogawa, J; Miyata, T; Su, Z-H (2011). "Phylogenetic relationships among insect orders based on three nuclear protein-coding gene sequences". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 58 (2): 169–180. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.11.001. PMID 21075208.

- Wang, X.; Engel, M.S.; Rafael, J.A.; Dang, K.; Wu, H.; Wang, Y.; Xie, Q.; Bu, W. (2013). "A unique box in 28S rRNA is shared by the enigmatic insect order Zoraptera and Dictyoptera". PLOS ONE. 8 (1): e53679. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...853679W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0053679. PMC 3536744. PMID 23301099.

- Choe, Jae C. (1997). "The evolution of mating systems in the Zoraptera: mating variations and sexual conflicts". In Choe, Jae C.; Crespi, Bernard J. (eds.). The Evolution of Mating Systems in Insects and Arachnids. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 130–145. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511721946.008. ISBN 978-0-511-72194-6.

- "Zoraptera (Insects)". what-when-how.com. Retrieved 2016-02-22.

- Choe, Jae C. (1994). "Sexual selection and mating system in Zorotypus gurneyi Choe (Insecta: Zoraptera)" (PDF). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, II. Determinants and Dynamics of Dominance. 34 (4): 233–237. doi:10.1007/bf00183473. hdl:2027.42/46900. ISSN 0340-5443.

- Choel, Jae C. (1994). "Sexual selection and mating system in Zorotypus gurneyi Choe (Insecta : Zoraptera), I. Dominance hierarchy and mating success". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 34 (2): 87–93. doi:10.1007/bf00164179. hdl:2027.42/46900. ISSN 0340-5443.

- Dallai, R.; et al. (12 May 2013). "Divergent mating patterns and a unique mode of external sperm transfer in Zoraptera: an enigmatic group of pterygote insects". Naturwissenschaften. 100 (6): 581–594. Bibcode:2013NW....100..581D. doi:10.1007/s00114-013-1055-0. ISSN 0028-1042. PMID 23666111.

- "The tiny insect with the massive sperm". New Scientist. No. 2919. 1 June 2013. p. 17.

- Engel, Michael (2007). "The Zorotypidae of Fiji (Zoraptera)" (PDF). Bishop Museum Occasional Papers.

- Yin, Ziwei; Cai, Chenyang; Huang, Diying (2018). "New zorapterans (Zoraptera) from Burmese amber suggest higher paleodiversity of the order in tropical forests". Cretaceous Research. 84: 168–172. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2017.11.028.

- MASHIMO, YUTA; MATSUMURA, YOKO; BEUTEL, ROLF G.; NJOROGE, LABAN; MACHIDA, RYUICHIRO (2018-03-04). "A remarkable new species of Zoraptera, Zorotypus asymmetristernum sp. n., from Kenya (Insecta, Zoraptera, Zorotypidae)". Zootaxa. 4388 (3): 407–416. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4388.3.6. ISSN 1175-5334. PMID 29690444.

- G O Poinar, Jr (1993-01-01). "Insects in Amber". Annual Review of Entomology. 38 (1): 145–159. doi:10.1146/annurev.en.38.010193.001045.

General references

- Costa JT 2006 Psocopera and Zoraptera. In: Costa JT The other Insect Societies. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA and London, UK pp 193–211

- Grimaldi, David; Engel, Michael S. (16 May 2005). Evolution of the Insects. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-26877-7. OCLC 56057971.

- Hubbard, Michael D. (1990). "A Catalog of the Order Zoraptera (Insecta)". Insecta Mundi. 4 (1–4).

- Rafael, José Albertino; Engel, Michael S. (2006). "A new species of Zorotypus from Central Amazonia, Brazil (Zoraptera: Zorotypidae)". American Museum Novitates. 3528: 1–11. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2006)3528[1:ANSOZF]2.0.CO;2. hdl:2246/5806.

- Kaddumi, Hani F. (2005). "Amber of Jordan, the Oldest Prehistoric Insects in Fossilized Resin". Publications of the Eternal River. Amman.: Museum of Natural History: 168. OCLC 235969870.

External links

- Tree of Life Zoraptera

- "Zorotypidae Silvestri, 1913". Zorapotera Species File.