Zaida Ben-Yusuf

Zaida Ben-Yusuf (21 November 1869 – 27 September 1933) was a New York–based portrait photographer[1] noted for her artistic portraits of wealthy, fashionable, and famous Americans during the turn of the 19th–20th century.

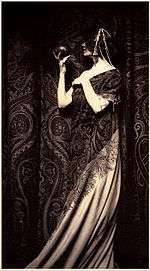

Zaida Ben-Yusuf | |

|---|---|

Self portrait, 1901 | |

| Born | Esther Zeghdda Ben Youseph Nathan 21 November 1869 London, England |

| Died | 27 September 1933 (aged 63) Brooklyn, New York |

| Known for | Photography |

In 1901, The Ladies Home Journal featured her and six other photographers as "The Foremost Women Photographers in America".[2][3] In 2008, the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery mounted an exhibition dedicated solely to Ben-Yusuf's work, re-establishing her as a key figure in the early development of fine art photography.[4][5]

Biography

Early life

Ben-Yusuf was born as Esther Zeghdda Ben Youseph Nathan in London, England, on 21 November 1869, the eldest daughter of a German mother, Anna Kind Ben-Youseph Nathan and an Algerian father, Mustapha Moussa Ben Youseph Nathan.[6] By 1881, her mother was living in Ramsgate and working as a governess[6] after separating from her husband and four daughters {Zaida (aged 11), Heidi (8), Leila (4) and Pearl (3)}.

Later in 1888, Anna Ben-Yusuf emigrated to Boston, Massachusetts where she had established a milliner's shop on Washington Street in Boston[6] by 1891.

In 1895, Ben-Yusuf followed in her mother's footsteps and emigrated to the United States where she worked as a milliner at 251 Fifth Avenue, New York.[6] She continued this for some time after becoming a photographer, writing occasional articles for Harpers Bazaar and The Ladies Home Journal on millinery.[6][7][8]

Photography career

In 1896, Ben-Yusuf began to be known as a photographer. In April 1896, two of her pictures were reproduced in The Cosmopolitan Magazine, and another study was exhibited in London as part of an exhibition put on by The Linked Ring.[6] She traveled to Europe later that year, where she met with George Davison, one of the co-founders of The Linked Ring, who encouraged her to continue her photography. She exhibited at their annual exhibitions until 1902.

In the spring of 1897, Ben-Yusuf opened her portrait photography studio at 124 Fifth Avenue, New York.[6] On 7 November 1897, the New York Daily Tribune ran an article about Ben-Yusuf's studio and her work creating advertising posters, which was followed by another profile in Frank Leslie's Weekly on 30 December.[6] Through 1898, she became increasingly popular as a photographer, with ten of her works in the National Academy of Design-hosted 67th Annual Fair of the American Institute. This was where her portrait of actress Virginia Earle won her third place in the Portraits and Groups class.[7][9] During November 1898, Ben-Yusuf and Frances Benjamin Johnston held a two-woman show with their works at the Camera Club of New York.[7]

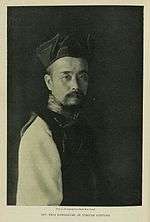

_by_Zaida_Ben-Yusuf.jpg)

In 1899, Ben-Yusuf met with F. Holland Day in Boston, and was photographed by him.[7] She relocated her studio to 578 Fifth Avenue, and exhibited in a number of exhibitions, including the second Philadelphia Photographic Salon.[7] She was also profiled in a number of publications, including an article on female photographers in The American Amateur Photographer, and a long piece in The Photographic Times in which Sadakichi Hartmann described her as an "interesting exponent of portrait photography".[7] In 1896 Ben-Yusuf was included in an exhibition organized by Linked Ring, Brotherhood of the London and continued to exhibit with them until 1902.[10]

In 1900, Ben-Yusuf corresponded with Johnston about an exhibition of American women photographers in Paris timed to coincide with the Universal Exposition. Ben-Yusuf had five portraits in the show, which traveled to Saint Petersburg, Moscow, and Washington, D.C.[7] She was also exhibited in Holland Day's exhibition, The New School of American Photography, for the Royal Photographic Society in London, and had four photographs selected by Alfred Stieglitz for the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1901, Scotland.[3][7]

In 1901, Ben-Yusuf wrote an article, "Celebrities Under the Camera", for the Saturday Evening Post, where she described her experiences with her sitters. By this stage she had photographed Grover Cleveland, Franklin Roosevelt, and Leonard Wood, amongst others.[3][7] For the September issue of Metropolitan Magazine she wrote another article, "The New Photography – What It Has Done and Is Doing for Modern Portraiture", where she described her work as being more artistic than most commercial photographers, but less radical than some of the better-known art photographers.[3] The Ladies Home Journal that November declared her to be one of the "foremost women photographers in America", as she began the first of a series of six illustrated articles on "Advanced Photography for Amateurs" in the Saturday Evening Post.[3]

Ben-Yusuf was listed as a member of the first American Photographic Salon when it opened in December 1904, although her participation in exhibitions was beginning to drop off. In 1906, she showed one portrait in the third annual exhibition of photographs at Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts, the last known exhibition of her work in her lifetime.[3]

Travels to Japan

In 1903, Ben-Yusuf traveled to Japan, where she toured Yokohama, Kobe, Nagasaki, Kyoto( where she rented a house), Tokyo and Nikkō.[3] This tour formed the basis for a series of four illustrated articles, "Japan Through My Camera", published in the Saturday Evening Post from 23 April 1904.[3] In February 1905, her essay on Kyoto appeared in Booklovers Magazine and Leslie's Monthly Magazine published an illustrated article on "Women in Japan". She also wrote about Japanese architecture and lectured on the subject, with some of her photographs illustrating a January 1906 article by Katharine Budd in Architectural Record, for which she submitted an article, "The Period of Daikan", which appeared the next month.[3]

In 1906, she published three photographs from a visit to Capri in the September issue of Photo Era, and in 1908, wrote three essays on life in England for the Saturday Evening Post.[3] She returned to New York in November 1908, but was back in London the following year. The London phone book for 1911 listed her as a photographer in Chelsea.[11] In 1912, Sadakichi Hartmann wrote that Ben-Yusuf had given up photography, and was living in the South Sea Islands.[11]

On 15 September, following the outbreak of World War I and the German invasion of France, Ben-Yusuf returned to New York from Paris, where she had been living at the time.[11] She applied for naturalization in 1919, describing herself as a photographer, and taking ten years off her age.[11] She continued to travel, visiting Cuba in 1920 and Jamaica in 1921.[11]

Later life

Ben-Yusuf took a post with the Reed Fashion Service in New York City in 1924, and lectured at local department stores on fashion related subjects.[11] In 1926, she was appointed style director for the Retail Millinery Association of New York, an organisation for which she later became director.[11]

By 1930, census records showed that Ben-Yusuf had married a textile designer, Frederick J. Norris. She died three years later on 27 September in the Methodist Episcopal Hospital in Brooklyn.[11]

Exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery

Ben-Yusuf's work was the subject of an exhibition, Zaida Ben-Yusuf: New York Portrait Photographer at the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery, which ran from 11 April through 1 September 2008. The curator, Frank H. Goodyear III, first learned about Ben-Yusuf when he discovered two of her photographs in 2003, depicting Daniel Chester French and Everett Shinn, and set forth to discover more about a photographer who had been almost completely forgotten.[5]

Goodyear suggested that gender discrimination might have led to Ben-Yusuf being forgotten, despite her significant contributions towards developing photography as a medium of artistic expression.[5] Photographic history had tended to focus on male photographers such as Stieglitz, and less so on the female photographers, even though it was one of the few occupations considered a respectable career for a single woman in late 19th and early 20th century New York.[5] Even in relatively progressive New York, where innovators in the arts, science, journalism and politics gathered, it was difficult for a single professional woman to support herself.[5]

Another reason for Ben-Yusuf's obscurity was that she had not bequeathed a significant archive of her work to a single institution, making it difficult to pull together enough examples to give her career the appropriate historical assessment.[5] Goodyear's exhibition at the Smithsonian acted as a showcase for Ben-Yusuf's work, re-establishing her as a key figure in fine art photographic history.[5]

References

- Crompton, Sarah (6 May 2016). "She takes a good picture: six forgotten female pioneers of photography". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- Ladies Home Journal November 1901

- Chronology of Zaida Ben-Yusuf, 1901–1906 on the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery website, accessed 30 March 2009. "Chronology of Zaida Ben-Yusuf, 1898–1900", 31 October 2018

- Zaida Ben Yusuf exhibition at the Smithsonian Archived 3 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Monsen, Lauren. "New Exhibition Resurrects Legacy of Groundbreaking Photographer: Ben-Yusuf produced memorable portraits that captured an era". America.gov. Archived from the original on 24 July 2010. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- Chronology of Zaida Ben-Yusuf, 1869–1898 on the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery website, accessed 30 March 2009 Archived 21 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Chronology of Zaida Ben-Yusuf, 1898–1900 on the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery website, accessed 30 March 2009 Archived 2 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Harpers Bazaar, Vol. 30 No. 5, published 30 January 1897

- "The 1898 American Institute Exhibition of Photographs". The American Amateur Photographer: 457. 1898.

She won a third bronze prize medal (class i. Portraits) on a full length portrait of Miss Virginia Earle

- Schwendener, Martha. "Ben-Yusuf, Zaida." Grove Art Online. 11 Feb. 2013; Accessed 26 Mar. 2020. https://www-oxfordartonline-com.ezproxy.ithaca.edu/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7002229182.

- Chronology of Zaida Ben-Yusuf, 1907–1933 on the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery website, accessed 30 March 2009 Archived 2 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- Goodyear, Frank H.; Wiley, Elizabeth O.; and Boone, Jobyl A.; Zaida Ben-Yusuf: New York portrait photographer (London, New York: Merrell; Washington: In association with National Portrait Gallery, 2008). ISBN 978-1-85894-439-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zaida Ben-Yusuf. |