York and Doncaster branch

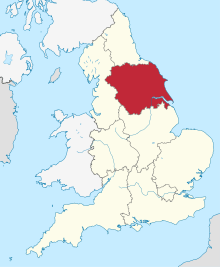

The York and Doncaster branch was a railway line that opened in 1871 connecting Doncaster with York via Selby in Yorkshire, England. This line later became part of the East Coast Main Line (ECML) and was the route that express trains took between London King's Cross, the north of England and Scotland. It was opened by the North Eastern Railway (NER) between York and Shaftholme Junction, some 4.5 miles (7.2 km) north of Doncaster railway station. Between its opening in 1871 and the grouping in 1923, the line was used by both the NER, and the Great Northern Railway (GNR). All of the intermediate local stations that had opened with the line in 1871 closed down in the 1950s and 1960s leaving just Selby open between the town of Doncaster and the city of York.

| York and Doncaster branch | |

|---|---|

The roadbridge over the Trans-Pennine Trail at Escrick | |

| Overview | |

| Other name(s) | York and Doncaster branch line East Coast Main Line (old route) |

| Type | Heavy rail High speed rail |

| Status | Partially closed |

| Locale | Yorkshire |

| Termini | York (historical) Selby (current) Doncaster |

| Stations | 11/12[note 1] |

| Operation | |

| Opened | 2 January 1871 |

| Owner | Network Rail |

| Operator(s) | |

| Technical | |

| Line length | 33.5 mi (53.9 km) |

| Track length | 27 mi (43 km) |

| Number of tracks | 2 |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge |

| Electrification | 25 kV overhead (partial) |

| York and Doncaster Line | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In the 1970s, a plan for extracting the coal from underneath the northern section of the line between Selby and York, led to British Rail building an avoiding line, the Selby Diversion, which fully opened to traffic in October 1983.[note 2] The southern section of the line between Doncaster and Selby is still open to enable trains from Doncaster to access the East Riding of Yorkshire and Lincolnshire.[note 3]

The trackbed of the line between Selby and York is now used partly by the A19 (as a bypass at Riccall), whilst the rest of the route forms part of the Trans-Pennine Trail and National Cycle Route 65.

History

At least two routes were available from the region of South Yorkshire[note 4] northwards into York by the time that the York to Doncaster Branch was opened in January 1871. George Hudson had already promoted his venture, the York and North Midland Railway, whilst the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway (L&Y) had their line which went through Knottingley.[1] The L&Y were against the NER building what would be a shorter line (by 10.5 miles (16.9 km)),[2] between Doncaster and York as it would take traffic away from their line. Nevertheless, the plan was approved in March 1864, and despite some financial problems, the line opened to traffic in January 1871.[3]

The Great Northern Railway achieved running powers over the line from the NER which allowed a mutually beneficial service for both companies. The GNR would run the long distance trains and the NER would operate the local services.[2] As the new line connected with Shaftholme Junction, the section south from there to Doncaster was controlled by the GNR, so the NER needed their permission to run into Doncaster.[4]

The works included an entirely new section of railway south from Chaloners Whin Junction, south of York, to Barlby Junction on the eastern side of Selby. The route then used the Hull and Selby line across the River Ouse on Selby Swing Bridge and into Selby railway station. The second part of the route was another new build going due south from Selby to Shaftholme Junction north of Doncaster. The whole route between York and Doncaster consisted of 2 miles (3.2 km) from York to Chaloners Whin Junction (already in existence), 12.5 miles (20.1 km) of new railway to Barlby Junction at Selby, 14.5 miles (23.3 km) from Selby to Shaftholme Junction, and then the last 4.5 miles (7.2 km) section to Doncaster on the existing GNR metals.[5] The cost of the new railway was £239,500 in 1871.[3]

There were no major engineering obstacles on the line apart from a swing bridge over the River Ouse at Naburn, just to the north of Naburn station.[6] Built to a design by Thomas Elliott Harrison, it was constructed of wrought iron which had two sections spanning 176 feet (54 m).[7] Only one of the spans was able to swing, this being the one that had a control tower on top of it.[8] In the first few years of operation, the bridge would be swung open to allow the passage of river traffic, and would only be moved into alignment with the railway when a train was due to pass.[9] During the National Railway strike of 1911, the bridge and its signal box were overrun with striking railwaymen. The military were sent in to retake the bridge.[10] The span was fixed in place by British Rail in 1956 as river traffic lessened in favour of ports downstream.[11]

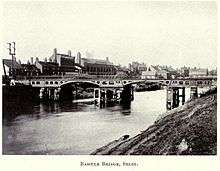

Another bridge spanned the River Ouse at Selby, just east of the station. This was originally a bascule bridge,[12] that was replaced in 1891 with a swing bridge.[13] The 1871 line also brought a new build station and Selby became an important junction on the routes between London and Edinburgh, and also on the Transpennine route to and from Hull.[14] The station at Selby had four through tracks, with the middle tracks having no platforms. The westbound and eastbound tracks were gauntletted over the bridge and were reformed from two lines over the bridge, to four on either side.[15] The gauntletting was removed in 1960, 23 years before the old ECML branch through Riccall was closed because of the Selby Diversion.[16]

Railway swing bridge, Naburn

Railway swing bridge, Naburn The original bascule bridge at Selby

The original bascule bridge at Selby.jpg) The replacement swing bridge at Selby

The replacement swing bridge at Selby

In 1989, the route northwards via the Selby Diversion was electrified,[17] whilst the former line to Selby northwards from Temple Hirst Junction remains un-electrified.[18]

Stations

The York to Doncaster line served the following stations;

| Name | Coordinates | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| York | 53.9583°N 1.0930°W | The original formation had trains that used the old York railway station. In 1877, a through station at York was built.[19] |

| Naburn | 53.9089°N 1.0859°W | New build station opened by the NER 2 January 1871.[20] Closed in June 1953.[21] |

| Escrick | 53.8697°N 1.0467°W | New build station opened by the NER 2 January 1871.[22] Closed in June 1953.[23] |

| Riccall | 53.8314°N 1.0531°W | New build station opened by the NER 2 January 1871.[24] Closed in September 1958.[21] |

| Selby | 53.7830°N 1.0634°W | First station on the west bank of the River Ouse opened in 1834, replaced by a new station with tracks across the Ouse in 1840.[12] The opening of the new York and Doncaster Branch line led to a new station being built to a design by Thomas Prosser in January 1871. |

| Temple Hirst | 53.7179°N 1.0893°W | New build station opened by the NER in 1871.[25] Closed to passengers in June 1961,[26] goods traffic ceased in 1964.[27] |

| Heck | 53.6828°N 1.0994°W | New build station opened by the NER in 1871.[28] Closed in September 1958.[26] |

| Balne | 53.6641°N 1.1056°W | New build station opened by the NER in 1871.[29] Closed in September 1958.[26] |

| Moss | 53.6220°N 1.1131°W | New build station opened by the NER in 1871.[30] Closed in June 1953.[26] |

| Joan Croft Halt | 53.5878°N 1.1218°W | Non-public station in use by crossing keepers and their families. Quick states the halt was in use between 1920 and 1955, but that it only appeared in the Working Timetable (WTT) in 1939, 1940 and lastly in June 1955.[31] |

| Arksey | 53.5515°N 1.1331°W | Opened by the Great Northern Railway 6 June 1848; closed to passenger traffic 5 August 1952.[32] |

| Doncaster | 53.5225°N 1.1395°W | Opened between 1850 and 1852.[33] |

Aside from the express trains that used the route, the timetable from 1910 shows that the section north of Selby had eight stopping services per day,[34] this had dropped by the 1930s shows three trains per day calling at all stations.[35] In 1946, the Bradshaws timetable shows some six local trains per day each way, though only one stopped at all of the stations on the line.[36]

Accidents

- 18 May 1883 - The station master at Escrick station was crossing the line as a freight train was engaged in the shunting of the goods sidings. The driver of the train whistled and threw the engine into reverse, but it knocked the station master down and removed both his legs below the knee. A passing express was stopped and took the injured man to York, but he died before it reached its destination.[37]

- 8 September 1896 - The signalman at the Naburn Bridge control cabin, was found dead on the track with his body "horribly mangled". A resultant inquiry surmised that as he was walking to work along the railway track, he crossed to the other line to avoid a train when he was hit by another train coming the other way.[38]

- 16 July 1952 - Riccall Gates Crossing was worked by one man who opened and closed the gates as well as setting the signals. The job was demanding because of the traffic, but also because the busy A19 was the road that used the crossing. The crossing keeper also had to communicate with the signal boxes which were next up and down the line and to manage the demands of the busy road traffic on the A19, who were impatient to get on their way. One car driver who parped his horn after a goods train had passed, was killed along with his wife when the confused signalman allowed him to start across the level crossing. On realising that a train was approaching from the north, the signalman waved his arms in a gesture which one witness said was encouraging the driver to speed up. Instead, the driver stopped on the level crossing and his car was crushed. The signalman was later found to have been negligent in his duties as he was discussing the cricket with a friend in the signal box whilst working the signals and the gates across the busy road. He was later jailed for manslaughter.[39]

- 15 November 1980 - a car drove around the automatic half Barriers of Riccall Turnhead Crossing just after midnight. An overnight container train heading south from Edinburgh was approaching the crossing and the driver of the locomotive testified that he saw the red lights of the crossing flashing and the barriers were down. For some reason, the car was driven around the barriers and the driver of the train observed the cars' headlights shine towards him, and then away from him, as it tried to negotiate its way around the barriers. The two occupants of the car were killed.[40]

- 28 February 2001 - the Great Heck rail crash. A Land Rover vehicle crashed off of the M62 motorway and onto the railway line at Great Heck. The vehicle was hit by a southbound passenger train, which derailed the train. The wreckage was then hit by a freight train carrying a load of coal weighing 1,800 tonnes (2,000 tons) going northwards. Ten people died with over 80 being injured. The Land Rover driver was later sentenced to five years in prison on ten counts of causing death by dangerous driving, as it was proven in court that he had fallen asleep at the wheel.[41]

Partial closure

In the 1970s, British Coal set about developing a working coalfield (the Selby Coalfield) to the north of Selby. To avoid subsidence on this section of line, a 14.5-mile (23.3 km) diversion (the Selby Diversion) was opened between Temple Hirst Junction, just south of Temple Hirst railway station and Colton Junction, some 6 miles (9.7 km) south of York railway station.[42] Both junctions were new to the railway and the whole cost of the project was £60 million, which was paid for entirely by British Coal.[43] This was seen as a good compromise as the estimated value of the coal underneath the railway was thought to have been worth over £1,000 million.[44]

At its furthest point away from the original formation, the Selby Diversion was still only 5 miles (8 km) west of Riccall.[45]

The stretch of trackbed between the sites of Riccall railway station and Barlby Junction is now the site of at the widened A19 road.[46] The section between Riccall and York now forms part of the Trans-Pennine Trail, and the National Route 65 which Sustrans purchased for the price of £1.[47] The route has a scale model of the solar system, with each planet staggered along the path at the correct proportional distances from each other. The swing bridge at Naburn also has a sculpture of a man fishing on the top of it; he is known as The Fisher of Dreams,[48][49] and is constructed of galvanised steel.[50]

The section of line between York and Riccall, was featured on the TV series Walks Around Britain in 2017, complete with a CGI film of how the railway would have looked in the days of steam.[51]

Notes

- See the stations section; Joan Croft Halt was not officially a public station.

- The northern section of the line between York and Hambleton Junction opened earlier in 1983 to allow for York to Hull trains to traverse the section.

- There is another line between Doncaster and the East Riding of Yorkshire which goes via Goole (the Hull and Doncaster Branch). Hull Trains services use the former York and Doncaster line via Selby

- At that time, the area was in the West Riding of Yorkshire.

References

- Hoole 1985, p. 47.

- Hoole 1983, p. 20.

- Batty 1991, p. 41.

- Joy 1984, p. 213.

- Allen, Cecil J (1964). The North Eastern Railway. London: Ian Allan. p. 137. OCLC 1068170488.

- Taylor, J P G (2015). Riccall : a village history. Wetherby: Oblong Creative. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-9575992-6-0.

- Tomlinson 1914, p. 644.

- Welbourn, Nigel (2018). Lost Lines Railway Treasures. Manchester: Crecy. p. 39. ISBN 9780860936916.

- "History of Naburn Swing Bridge - Railway to Greenway". railwaytogreenway.org. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Lewis, Stephen (15 April 2019). "The 1911 rail strike that almost caused a disaster at Scarborough Bridge". infoweb.newsbank.com. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Appleby 1993, p. 75.

- Body 1989, p. 152.

- "A booklet to mark the 175th anniversary of the opening of the Hull to Selby railway" (PDF). scs.statementcms.co.uk. July 2015. p. 8. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- Historic England. "Selby Railway Station building on Up Platform, Canopies on Both PLatforms Footbridge and Benches (Grade II) (1365687)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Brailsford, Martyn, ed. (2016). Railway track diagrams. Book 2, Eastern (4 ed.). Frome: Trackmaps. 38A. ISBN 978-0-9549866-8-1.

- Chapman 2002, p. 33.

- "ECML: Electrification as it used to be". railengineer.co.uk. 27 November 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Brailsford, Martyn, ed. (2016). Railway track diagrams. Book 2, Eastern (4 ed.). Frome: Trackmaps. 18A. ISBN 978-0-9549866-8-1.

- "England's oldest railway stations as they used to look". The Telegraph. 26 March 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- Quick 2009, p. 284.

- Burgess, Neil (2011). The lost railways of Yorkshire's East Riding. Catrine: Stenlake. p. 43. ISBN 9781840335521.

- Quick 2009, p. 166.

- Ellis, Norman (1995). North Yorkshire railway stations. Ochiltree: Stenlake. p. 53. ISBN 1-872074-63-4.

- Quick 2009, p. 330.

- Hoole 1985, p. 192.

- Burgess, Neil (2014). The lost railways of Yorkshire's West Riding. The central section : Bradford, Halifax, Huddersfield, Leeds, Wakefield. Catrine: Stenlake. p. 83. ISBN 9781840336573.

- Body 1989, p. 169.

- Hoole 1985, p. 169.

- Hoole 1985, p. 152.

- Hoole 1985, p. 177.

- Quick 2009, p. 227.

- Young, Alan (2015). Lost stations of Yorkshire; the West Riding. Kettering: Silver Link. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-85794-438-9.

- Body, Geoffrey (1986). Railways of the Eastern Region. Vol. 1, Southern operating area. London: Guild. p. 55. ISBN 0850597129.

- Suggitt 2007, p. 119.

- Body 1989, p. 154.

- 1946 June Bradshaw's Railway Timetable - British Isles at the Internet Archive

- "The Escrick Railway Station Fatality". The York Herald (9, 979). Col F. 22 May 1883. p. 3. OCLC 877360086.

- "Fatalities to Signalmen". The York Herald (14, 125). Col F. 12 September 1896. p. 13. OCLC 877360086.

- Gray 2013, pp. 79–80.

- Gray 2013, p. 88.

- "Rail deaths driver blames 'fate'". BBC News. 28 February 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- Brailsford, Martyn, ed. (2016). Railway track diagrams. Book 2, Eastern (4 ed.). Frome: Trackmaps. 18–19. ISBN 978-0-9549866-8-1.

- Suggitt 2007, p. 118.

- Hoole 1983, p. 22.

- Taylor, J P G (2015). Riccall : a village history. Wetherby: Oblong Creative. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-9575992-6-0.

- Appleby 1993, p. 74.

- "York to Selby". sustrans.org.uk. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- Suggitt 2007, p. 120.

- "Sculpture dream comes true". York Press. 2 August 2001. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- "Cycle guide: York to Selby". The Guardian. 3 March 2007. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Laycock, Mike (5 December 2016). "Film-maker recreates age of steam on closed York-Selby rail line". infoweb.newsbank.com. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

Sources

- Appleby, Ken (1993). Britain's Rail Super Centres: York. Shepperton: Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-2072-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Batty, Stephen R (1991). Rail Centres: Doncaster. Shepperton: Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-2004-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Body, Geoffrey (1989). Railways of the Eastern Region Volume 2: Northern Operating Area. Wellingborough: Patrick Stephens. ISBN 1-85260-072-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chapman, Stephen (2002). Railway Memories No. 14; Selby and Goole. Todmorden: Bellcode Books. ISBN 1-871233-14-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gray, Adrian (2013). East Coast Main Line Disasters. Easingwold: Pendragon. ISBN 978-1-899816-19-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hoole, Ken (1985). Railway Stations of the North East. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-8527-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hoole, Ken (1983). Rail Centres: York. Shepperton: Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-1320-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Joy, David (1984). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain Volume 8: South and West Yorkshire (2 ed.). Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-946537-11-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Quick, Michael (2009). Railway Passenger Stations in Great Britain (4 ed.). Oxford: Railway and Canal Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-901461-57-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Suggitt, Gordon (2007). Lost Railways of North & East Yorkshire. Newbury: Countryside Books. ISBN 978-1-85306-918-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tomlinson, William Weaver (1914). The North Eastern Railway; its Rise and Development. London: Longmans & Co. OCLC 1049905072.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)