Yevgeny Zamyatin

Yevgeny Ivanovich Zamyatin[1] (Russian: Евге́ний Ива́нович Замя́тин, IPA: [jɪvˈɡʲenʲɪj ɪˈvanəvʲɪtɕ zɐˈmʲætʲɪn]; 20 January (Julian) / 1 February (Gregorian), 1884 – 10 March 1937), sometimes anglicized as Eugene Zamyatin, was a Russian author of science fiction and political satire. He is most famous for his 1921 novel We, a story set in a dystopian future police state.

Yevgeny Zamyatin | |

|---|---|

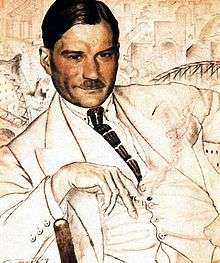

Yevgeny Zamyatin by Boris Kustodiev (1923). | |

| Born | Yevgeny Ivanovich Zamyatin 1 February 1884 Lebedyan, Russian Empire |

| Died | 10 March 1937 (aged 53) Paris, Third French Republic |

| Occupation | Novelist, journalist |

| Genre | Science fiction, Satire |

| Notable works | We |

Despite having been a prominent Old Bolshevik, Zamyatin was deeply disturbed by the policies pursued by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) following the October Revolution. In 1921, We became the first work banned by the Soviet censorship board. Ultimately, Zamyatin arranged for We to be smuggled to the West for publication. The subsequent outrage this sparked within the Party and the Union of Soviet Writers led directly to Zamyatin's successful request for exile from his homeland. Due to his use of literature to criticize Soviet society, Zamyatin has been referred to as one of the first Soviet dissidents.

Early life

Zamyatin was born in Lebedyan, Tambov Governorate, 300 km (186 mi) south of Moscow. His father was a Russian Orthodox priest and schoolmaster, and his mother a musician. In a 1922 essay, Zamyatin recalled, "You will see a very lonely child, without companions of his own age, on his stomach, over a book, or under the piano, on which his mother is playing Chopin."[2]

He may have had synesthesia since he gave letters and sounds qualities. For instance, he saw the letter Л as having pale, cold and light blue qualities.[3]

He studied engineering for the Imperial Russian Navy in Saint Petersburg, from 1902 until 1908. During this time, Zamyatin joined the Marxist-Leninist, or Bolshevik, faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party.[4] He was arrested by the Okhrana during the Russian Revolution of 1905 and sent into internal exile in Siberia. However, he escaped and returned to Saint Petersburg where he lived illegally before moving to the Grand Duchy of Finland in 1906 to finish his studies.

After returning to Russia, he began to write fiction as a hobby. He was arrested and exiled a second time in 1911, but amnestied in 1913. His Uyezdnoye (A Provincial Tale) in 1913, which satirized life in a small Russian town, brought him a degree of fame. The next year he was tried for defaming the Imperial Russian Army in his story Na Kulichkakh (At the world's end).[5] He continued to contribute articles to various Marxist newspapers.

After graduating as an engineer for the Imperial Russian Navy, Zamyatin worked professionally at home and abroad. In 1916 he was sent to the United Kingdom to supervise the construction of icebreakers[6] at the shipyards in Walker and Wallsend while living in Newcastle upon Tyne.

Zamyatin later recalled, "In England, I built ships, looked at ruined castles, listened to the thud of bombs dropped by German zeppelins, and wrote The Islanders. I regret that I did not see the February Revolution, and know only the October Revolution (I returned to Petersburg, past German submarines, in a ship with lights out, wearing a life belt the whole time, just in time for October). This is the same as never having been in love and waking up one morning already married for ten years or so."[7]

Soviet Dissident

Zamyatin's The Islanders, satirizing English life, and the similarly themed A Fisher of Men, were both published after his return to Russia in late 1917. After the Russian Revolution of 1917 he edited several journals, lectured on writing, and edited Russian translations of works by Jack London, O. Henry, H. G. Wells, and others.

His works became increasingly satirical and critical toward the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Even though he was an Old Bolshevik, Zamyatin came to disagree more and more with the Party's policies, particularly regarding the suppression of freedom of speech, and the censorship of literature,the media, and the arts.

In his 1921 essay I Am Afraid, Zamyatin wrote: "True literature can exist only when it is created, not by diligent and reliable officials, but by madmen, hermits, heretics, dreamers, rebels and skeptics." [8]

In his 1923 essay, On Literatute, Revolution, Entropy, and Other Matters, Zamyatin wrote, "The law of revolution is red, fiery, deadly; but this death means the birth of a new life, a new star. And the law of entropy is cold, ice blue, like the icy interplanetary infinities. The flame turns from red to an even, warm pink, no longer deadly, but comfortable. The sun ages into a planet, convenient for highways, stores, beds, prostitutes, prisons; this is the law. And if the planet is to be kindled into youth again, it must be set on fire, it must be thrown off the smooth highway of evolution: this is the law. The flame will cool tomorrow, or the day after tomorrow (in the Book of Genesis days are equal to years, ages). But someone must see this already, and speak heretically today about tomorrow. Heretics are the only (bitter) remedy against the entropy of human thought. When the flaming, seething sphere (in science, religion, social life, art) cools, the fiery magma becomes coated with dogma - a rigid, ossified, motionless crust. Dogmatization in science, religion, social life, or art is the entropy of thought. What has become dogma no longer burns; it only gives off warmth - it is tepid, it is cool. Instead of the Sermon on the Mount, under the scorching sun, to upraised-arms and sobbing people, there there is drowsy prayer in a magnificent abbey. Instead of Galileo's, 'Be still, it turns!' there are disspasionate computations in a well-heated room in an observatory. On the Galileos, the epigones build their own structures, slowly, bit by bit, like corals. This is the path of evolution - until a new heresy explodes the crush of dogma and all the edifices of the most enduring which have been raised upon it. Explosions are not very comfortable. And therefore the exploders, the heretics, are justly exterminated by fire, by axes, by words. To every today, to every civilization, to the laborious, slow, useful, most useful, creative, coral-building work, heretics are a threat. Stupidly, recklessly, they burst into today from tomorrow; they are romantics. Babeuf was justly beheaded in 1797; he leaped into 1797 across 150 years. It is just to chop off the head of a heretical literature which challenges dogma; this literature is harmful. But harmful literature is more useful than useful literature, for it is anti-entropic, it is a means of challenging calcification, sclerosis, crust, moss, quiescence. It is Utopian, absurd - like Babeuf in 1797. It is right 150 years later."[9]

These attitudes, which the Party considered Deviationism made Zamyatin's position increasingly difficult as the 1920s wore on.

Zamyatin also wrote a number of short stories, in fairy tale form, that constituted satirical criticism of Communist ideology. In one story, the mayor of a city decides that to make everyone happy he must make everyone equal. The mayor then forces everyone, himself included, to live in a big barrack, then to shave their heads to be equal to the bald, and then to become mentally disabled to equate intelligence downward. This plot is very similar to that of The New Utopia (1891) by Jerome K. Jerome whose collected works were published three times in Russia before 1917.[10] In its turn, Kurt Vonnegut's short story "Harrison Bergeron" (1961) bears distinct resemblances to Zamyatin's tale.

In 1923, Zamyatin arranged for the manuscript of his dystopian science fiction novel We to be smuggled to E.P. Dutton and Company in New York City. After being translated into English by Russian refugee Gregory Zilboorg, the novel was published in 1924.

Then, in 1927, Zamyatin went much further. He smuggled the original Russian text to Marc Lvovich Slonim (1894–1976), the editor of an anti-communist Russian émigré magazine and publishing house based in Prague. To the fury of the Soviet State, copies of the Czechoslovakian edition began being smuggled back to the USSR and secretly passed from hand to hand. Zamyatin's secret dealings with Western publishers triggered a mass offensive by the Soviet State against him. As a result, he was blacklisted from publishing anything in his homeland.

Max Eastman, an American Communist who had similarly broken with his former beliefs, described the Politburo's war against Zamyatin in his book Artists in Uniform.[11]

In 1931, Zamyatin appealed directly to Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin, requesting permission to leave the Soviet Union. In this letter Zamyatin wrote, "I do not wish to conceal that the basic reason for my request for permission to go abroad with my wife is my hopeless position here as a writer, the death sentence that has been pronounced upon me as a writer here at home.".[12]

During the spring of 1931, Zamyatin asked Maxim Gorky, to intercede with Stalin on his behalf.[13][14]

After Gorky's death, Zamyatin wrote, "One day, Gorky's secretary telephoned to say that Gorky wished me to have dinner with him at his country home. I remember clearly that extraordinarily hot day and the rainstorm - a tropical downpour- in Moscow. Gorky's car sped through a wall of water, bringing me and several other invited guests to dinner at his home. It was a literary dinner, and close to twenty people sat around the table. At first Gorky was silent, visibly tired. Everybody drank wine, but his glass contained water - he was not allowed to drink wine. After a while, he rebelled, poured himself a glass of wine,then another and another, and became the old Gorky. The storm ended, and I walked out onto the large stone terrace. Gorky followed me immediately and said to me, 'The affair of your passport is settled. But if you wish, you can return the passport and stay.' I said I would go. Gorky frowned and went back to the other guests in the dining room. It was late. Some of the guests remained overnight; others, including myself, were returning to Moscow. In parting, Gorky said, 'When shall we meet again? If not in Moscow, then perhaps in Italy? If I go there, you must come to see me! In any case, until we meet again, eh?' This was the last time I saw Gorky."[15]

Emigration and death

After their emigration, Zamyatin and his wife settled in Paris. The screenplay to French film maker Jean Renoir's 1936 adaptation of Maxim Gorky's stage play The Lower Depths was co-written by Zamyatin.

Zamyatin later wrote, "Gorky was informed of this, and wrote that he was pleased at my participation in the project, that he would like to see the adaptation of his play, and would wait to receive the manuscript. The manuscript was never sent: by the time it was ready for mailing, Gorky was dead."[16]

Yevgeny Zamyatin died in poverty[17] of a heart attack in 1937. Only a small group of friends were present for his burial. However, one of the mourners was his Russian language publisher Marc Lvovich Slonim, who had befriended the Zamyatins after their arrival in the West. Yevgeny Zamyatin's grave can be found in Cimetière de Thiais, in the Paris suburb of the same name.

Legacy

We has often been discussed as a political satire aimed at the police state of the Soviet Union. There are many other dimensions, however. It may variously be examined as (1) a polemic against the optimistic scientific socialism of H. G. Wells, whose works Zamyatin had previously published, and with the heroic verses of the (Russian) Proletarian Poets, (2) as an example of Expressionist theory, and (3) as an illustration of the archetype theories of Carl Jung as applied to literature. George Orwell believed that Aldous Huxley's Brave New World (1932) must be partly derived from We.[18] However, in a 1962 letter to Christopher Collins, Huxley says that he wrote Brave New World as a reaction to H.G. Wells' utopias long before he had heard of We.[19][20] Kurt Vonnegut said that in writing Player Piano (1952) he "cheerfully ripped off the plot of Brave New World, whose plot had been cheerfully ripped off from Yevgeny Zamyatin's We."[21] In 1994, We received a Prometheus Award in the Libertarian Futurist Society's "Hall of Fame" category.[22]

We, the 1921 Russian novel, directly inspired:

- Aldous Huxley's Brave New World (1932)[23]

- Ayn Rand's Anthem (1938)[24]

- George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949)[25]

- Kurt Vonnegut's Player Piano (1952)[26]

- Ursula K. Le Guin's The Dispossessed (1974)[27]

Major writings

- Uezdnoe (Уездное), 1913 – 'A Provincial Tale' (tr. Mirra Ginsburg, in The Dragon: Fifteen Stories, 1966)

- Na kulichkakh (На куличках), 1914 – A Godforsaken Hole (tr. Walker Foard, 1988)

- Ostrovitiane (Островитяне), 1918 – 'The Islanders' (tr. T.S. Berczynski, 1978) / 'Islanders' (tr. Sophie Fuller and Julian Sacchi, in Islanders and the Fisher of Men, 1984)

- Mamai (Мамай), 1921 – 'Mamai' (tr. Neil Cornwell, in Stand, 4. 1976)

- Lovets chelovekov (Ловец человеков), 1921 – 'The Fisher of Men' (tr. Sophie Fuller and Julian Sacchi, in Islanders and the Fisher of Men, 1984)

- Peshchera (Пещера), 1922 – 'The Cave' (tr. Mirra Ginsburg, Fantasy and Science Fiction, 1969) – The House in the Snow-Drifts (Dom v sugrobakh), film adaptation in 1927, prod. Sovkino, dir. Friedrich *Ermler, starring Fyodor Nikitin, Tatyana Okova, Valeri Solovtsov, A. Bastunova

- Ogni sviatogo Dominika (Огни святого Доминика), 1922 (play)

- Bol'shim detiam skazki (Большим детям сказки), 1922

- Robert Maier (Роберт Майер), 1922

- Gerbert Uells (Герберт Уэллс), 1922 [H.G. Wells]

- On Literature, Revolution, and Entropy, 1924

- Rasskaz o samom glavnom (Рассказ о самом главном), 1924 – 'A Story about the Most Important Thing' (tr. Mirra Ginsburg, in *The Dragon: Fifteen Stories, 1966)

- Blokha (Блоха), 1926 (play, based on Leskov's folk-story 'Levsha, translated as 'The Left-Handed Craftsman')

- Obshchestvo pochotnykh zvonarei (Общество почетных звонарей), 1926 (play)

- Attila (Аттила), 1925–27

- My: Roman (Мы: Роман), 'We: A Novel' 1927 (translations: Gregory Zilboorg, 1924; Bernard Guilbert Guerney, 1970, Mirra Ginsburg, 1972; Alex Miller, 1991; Clarence Brown, 1993; Natasha Randall, 2006; first Russian-language book publication 1952, U.S.) – Wir, TV film in 1982, dir. Vojtěch Jasný, teleplay Claus Hubalek, starring Dieter Laser, Sabine von Maydell, Susanne nAltschul, Giovanni Früh, Gert Haucke

- Nechestivye rasskazy (Нечестивые рассказы), 1927

- Severnaia liubov' (Северная любовь), 1928

- Sobranie sochinenii (Собрание сочинений), 1929 (4 vols.)

- Zhitie blokhi ot dnia chudesnogo ee rozhdeniia (Житие блохи от дня чудесного ее рождения), 1929

- 'Navodnenie', 1929 – The Flood (tr. Mirra Ginsburg, in The Dragon: Fifteen Stories, 1966) – Film adaptation in 1994, dir. Igor Minayev, starring Isabelle Huppert, Boris Nevzorov, Svetlana Kryuchkova, Mariya Lipkina

- Sensatsiia, 1930 (from the play The Front Page, by Ben Hecht and Charles Mac Arthur)

- Dead Man's Sole, 1932 tr. unknown

- Nos: opera v 3-kh aktakh po N.V. Gogoliu, 1930 (libretto, with others) – The Nose: Based on a Tale by Gogol (music by Dmitri Shostakovich; tr. Merle and Deena Puffer, 1965)

- Les Bas-Fonds / The Lower Depths, 1936 (screenplay based on Gorky's play) – Film produced by Films Albatros, screenplay Yevgeni Zamyatin (as E. Zamiatine), Jacques Companéez, Jean Renoir, Charles Spaak, dir. Jean Renoir, starring Jean Gabin, Junie Astor, Suzy Prim, Louis Jouvet

- Bich Bozhii, 1937

- Litsa, 1955 – A Soviet Heretic: Essays (tr. Mirra Ginsburg, 1970)

- The Dragon: Fifteen Stories, 1966 (tr. Mirra Ginsburg, reprinted as The Dragon and Other Stories)

- Povesti i rasskazy, 1969 (introd. by D.J. Richards)

- Sochineniia, 1970–88 (4 vols.)

- Islanders and the Fisher of Men, 1984 (tr. Sophie Fuller and Julian Sacchi)

- Povesti. Rasskazy, 1986

- Sochineniia, 1988 (ed. T.V. Gromov)

- My: Romany, povesti, rasskazy, skazki, 1989

- Izbrannye proizvedeniia: povesti, rasskazy, skazki, roman, pesy, 1989 (ed. A.Iu. Galushkin)

- Izbrannye proizvedeniia, 1990 (ed. E. Skorosnelova)

- Izbrannye proizvedeniia, 1990 (2 vols., ed. O. Mikhailov)

- Ia boius': literaturnaia kritika, publitsistika, vospominaniia, 1999 (ed. A.Iu. Galushkin)

- Sobranie sochinenii, 2003–04 (3 vols., ed. St. Nikonenko and A. Tiurina)

Notes

- His last name is often transliterated as Zamiatin or Zamjatin. His first name is sometimes translated as Eugene.

- A Soviet Heretic: Essays by Yevgeny Zamyatin, Edited and translated by Mirra Ginsburg, University of Chicago Press 1970. Page 3.

- Introduction to Randall's translation of We.

- https://www.hesperuspress.com/yevgeny-zamyatin.html

- https://www.hesperuspress.com/yevgeny-zamyatin.html

- The Russian writer who inspired Orwell and Huxley, Russia Beyond The Headlines

- A Soviet Heretic, page 4.

- "I Am Afraid" (1921) p. 57, in: A Soviet Heretic. trans. Mirra Ginsberg (London: Quartet Books, 1991). p. 53-58

- Yevgeny Zamyatin (1970), A Soviet Heretic: Essays by Yevgeny Zamyatin, University of Chicago Press. Pages 108-109.

- "The New Utopia" (PDF). Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- Max Eastman, Artists in Uniform: A Study of Literature and Bureaucratism, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1934) pp. 82–93

- Yevgeny Zamyatin: Letter to Stalin. A Soviet Heretic: Essays Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press, 1970; pg. xii.

- http://spartacus-educational.com/RUSzamyatin.htm

- Yevgeny Zamyatin: A Soviet Heretic: Essays by Yevgeny Zamyatin Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press, 1970; pg. 257.

- Yevgeny Zamyatin: A Soviet Heretic: Essays by Yevgeny Zamyatin Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press, 1970; pg. 257.

- Yevgeny Zamyatin (1970), A Soviet Heretic: Essays Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press, pg. 258.

- https://www.hesperuspress.com/yevgeny-zamyatin.html

- Orwell (1946).

- Russell, p. 13.

- "Leonard Lopate Show". WNYC. 18 August 2006. Archived from the original on 22 August 2006. (radio interview with We translator Natasha Randall)

- Playboy interview with Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. Archived 10 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine, July 1973.

- "Libertarian Futurist Society: Prometheus Awards". Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- Blair E. 2007. Literary St. Petersburg: a guide to the city and its writers. Little Bookroom, p.75

- Mayhew R, Milgram S. 2005. Essays on Ayn Rand's Anthem: Anthem in the Context of Related Literary Works. Lexington Books, p.134

- Bowker, Gordon (2003). Inside George Orwell: A Biography. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 340. ISBN 0-312-23841-X.

- Staff (1973). "Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. Playboy Interview". Playboy Magazine Archived 7 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Le Guin UK. 1989. The Language of the Night. Harper Perennial, p.218

References

- Collins, Christopher. Evgenij Zamjatin: An Interpretive Study. The Hague and Paris, Mouton & Co. 1973. Examines his work as a whole and includes articles earlier published elsewhere by the author: We as Myth, Zamyatin, Wells and the Utopian Literary Tradition, and Islanders.

- Cooke, Brett (2002). Human Nature in Utopia: Zamyatin's We. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

- Fischer, Peter A. (Autumn 1971). "Review of The Life and Works of Evgenij Zamjatin by Alex M. Shane". Slavic and East European Journal. 15 (3): 388–390. doi:10.2307/306850. JSTOR 306850.

- Kern, Gary, "Evgenii Ivanovich Zamiatin (1884–1937)," Dictionary of Literary Biography, vol. 272: Russian Prose Writers Between the World Wars, Thomson-Gale, 2003, 454–474.

- Kern, Gary, ed (1988). Zamyatin's We. A Collection of Critical Essays. Ann Arbor, MI: Ardis. ISBN 0-88233-804-8.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Myers, Alan (1993). "Zamiatin in Newcastle: The Green Wall and The Pink Ticket". The Slavonic and East European Review. 71 (3): 417–427. Archived from the original on 18 June 2013.

- Richards, D.J. (1962). Zamyatin: A Soviet Heretic. London: Bowes & Bowes.

- Russell, Robert (1999). Zamiatin's We. Bristol: Bristol Classical Press.

- Shane, Alex M. (1968). The Life and Works of Evgenij Zamjatin. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Zamiatin, Evgenii Ivanovich (1988). Selections (in Russian). sostaviteli T.V. Gromova, M.O. Chudakova, avtor stati M.O. Chudakova, kommentarii Evg. Barabanova. Moskva: Kniga. ISBN 5-212-00084-X. (bibrec) (bibrec (in Russian))

- We was first published in the USSR in this collection of Zamyatin's works.

- Zamyatin, Yevgeny (1966). The Dragon: Fifteen Stories. Mirra Ginsburg (trans. and ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Zamyatin, Yevgeny (1970). A Soviet Heretic : Essays by Yevgeny Zamyatin. Mirra Ginsburg (trans. and ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Zamyatin, Yevgeny (1984). Islanders & The Fisher of Men. Sophie Fuller and Julian Sacchi (trans.). Edinburgh: Salamander Press.

- Zamyatin, Evgeny (1988). A Godforsaken Hole. Walker Foard (trans.). Ann Arbor, MI: Ardis.

- Zamyatin, Yevgeny (2006). We. Natasha Randall (trans.). NY: Modern Library. ISBN 0-8129-7462-X.

- Zamyatin, Yevgeny (2015). The Sign: And Other Stories. John Dewey (trans.). Gillingham: Brimstone Press. ISBN 9781906385545.

- Zamyatin, Yevgeny. We. List of translations.

- Zamyatin, Yevgeny. Collected works (in Russian) including his Autobiography (1929) and Letter to Stalin (1931)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Yevgeny Zamyatin |

- We (1924) Zamyatin's novel, as translated by Gregory Zilboorg.

- The Sign: And Other Stories A collection of stories by Zamyatin (1913–28), as translated by John Dewey.

- A Godforsaken Hole (1914) Zamyatin's novella, as translated by Walker Foard.

- Mamai (1920) Zamyatin's short story, as translated by Neil Cornwell.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2004.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: unfit url (link) (1935) Zamyatin's short story, as translated by Eric Konkol.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: unfit url (link) Zamyatin's short story, as translated by Andrew Glikin-Gusinsky.

- Petri Liukkonen. "Yevgeny Zamyatin". Books and Writers

- Encyclopedia of Soviet Writers biography of Yevgeny Zamyatin

- Yevgeny Zamyatin at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Zamyatin in Newcastle updates articles by Alan Myers published in Slavonic and East European Review.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original on 19 March 2009. Retrieved 9 September 2006.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: unfit url (link) brief, illustrated biography by Tatyana Kukushkina

- Riggenbach, Jeff (10 March 2010). "Yevgeny Zamyatin: Libertarian Novelist". Mises Daily. Ludwig von Mises Institute.

- Yevgeny Zamyatin Spartacus Educational website by John Simkin