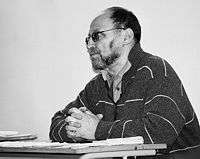

Dmitri Prigov

Dmitri Aleksandrovich Prigov (Russian: Дми́трий Алекса́ндрович При́гов, 5 November 1940 in Moscow – 16 July 2007 in Moscow[1]) was a Russian writer and artist. Prigov was a dissident during the era of the Soviet Union and was briefly sent to a psychiatric hospital in 1986.[2]

Dmitri Aleksandrovich Prigov | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | Дмитрий Александрович Пригов |

| Born | 5 November 1940 Moscow, Soviet Union |

| Died | 16 July 2007 (aged 66) Moscow, Russian Federation |

| Occupation | Writer, artist |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Citizenship | |

Early life and career

Born in Moscow, Russian SFSR, Prigov started writing poetry as a teenager. He was trained as a sculptor, however, at the Stroganov Art Institute in Moscow and later worked as an architect as well as designing sculptures for municipal parks.[2]

Artistic career

Prigov and his friend Lev Rubinstein were leaders of the conceptual art school started in the 1960s viewing performance as a form of art. He was also known for writing verse on tin cans.[2]

He was a prolific poet having written nearly 36,000 poems by 2005.[2] For most of the Soviet Era, his poetry was circulated underground as Samizdat. It was not officially published until the end of the Communist era.[1] His work was widely published in émigré publications and Slavic studies journals well before it was officially distributed.

In 1986, the K.G.B arrested Prigov, who performed a street action by handing poetic texts to passers-by, and sent him to a psychiatric institution before he was freed after protests by poets such as Bella Akhmadulina.[2]

From 1987 he started to be published and exhibited officially, and in 1991 he joined the Writers' Union. He had been a member of the Artists' Union from 1975.

Prigov took part in an exhibition in the USSR in 1987: his works were presented in the framework of the Moscow projects "Unofficial Art" and "Modern Art". In 1988 his personal exhibition took place in the USA, in Struve's Gallery in Chicago. Afterwards his works were many times exhibited in Russia and abroad.

Prigov also wrote the novels Live in Moscow and Only My Japan, and was an artist with works at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art.[3] He had many strings to his bow writing plays and essays, creating drawings, video art and installations and even performing music.[2]

Prigov, together with philosopher Mikhail Epstein, is credited with introducing the concept of "new sincerity" (novaia iskrennost' ) as a response to the dominant sense of absurdity in late Soviet and post-Soviet culture.[4][5] Prigov referred to a "shimmering aesthetics" that (as explained by Epstein) "is defined not by the sincerity of the author or the quotedness of his style, but by the mutual interaction of the two."[4]

In 1993 Prigov was awarded Pushkin Prize of Alfred Toepfer Stiftung F.V.S. and in 2002 he won Boris Pasternak Prize.

Dmitri Prigov died from a heart attack in 2007, aged 66, in Moscow. He had been planning an event where he would sit in a wardrobe reading poetry while being carried up 22 flights of stairs at Moscow State University by members of Voina Group.[1]

In 2011 Hermitage Museum presented an important monographic exhibition of Prigov's art in Venice during 54th Biennale.

Spelling of his name

Prigov's name in his native Russian Cyrillic lettering, Дми́трий Алекса́ндрович При́гов, has been rendered in English in various ways, with variations in the spelling of his first and middle names:

- Dimitri Prigov – Associated Press,[6] The New York Times

- Dimitrii Aleksandrovich Prigov[7]

- Dimitrij Aleksandrovich Prikov, Russian Literature, a periodical[8]

- Dmitry Aleksandrovich Prigov – Encyclopædia Britannica[9]

- Dimitry Prigov – The St. Petersburg Times (English language, Russia)[10] The Moscow Times[11]

Selected filmography

- Khrustalyov, My Car! (1998)

- Taxi Blues (1990)

References

- Dmitri Prigov, leader of conceptualist school, dies at age 66 news agency AP via International Herald Tribune, 16 July 2007

- New York Times "Dmitri Prigov, 66, Poet Who Challenged Soviet Authority, Dies" 20 July 2007

- Russian Culture Navigator Archived 17 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Mikhail Epstein, "On the Place of Postmodernism in Postmodernity," in Mikhail Epstein, Aleksandr Genis, Slobodanka Vladiv-Glover, eds., Russian Postmodernism: New Perspectives on Post-Soviet Culture (Berghahn Books, 1999), ISBN 978-1-57181-098-4, p. 457, excerpt available at Google Books.

- Alexei Yurchak, "Post-Post-Communist Sincerity: Pioneers, Cosmonauts, and Other Soviet Heroes Born Today," in Thomas Lahusen and Peter H. Solomon, eds., What Is Soviet Now?: Identities, Legacies, Memories (LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster, 2008), ISBN 978-3-8258-0640-8, p.258-59, excerpt available at Google Books.

- "Obituaries in the News", USA Today, Associated Press wire stories, including "Dimitri Prigov" brief obituary; see also "Russian poet Dmitri Prigov dies, age 66", version of same AP article at The Free Online Library website; both retrieved 14 January 2009

- Lipovetsky, Mark, and Eliot Borenstein, Russian Postmodernist Fiction: Dialogue with Chaos, p 302, published by M.E. Sharpe, 1999, ISBN 978-0-7656-0177-3

- as noted in a bibliographic listing in Reference Guide to Russian Literature, p 663, Neil Cornwell, Nicole Christian, editors, published by Taylor & Francis, 1998, ISBN 978-1-884964-10-7; the Reference Guide itself uses "Dimitrii Aleksandrovich Prigov"; retrieved 14 January 2009

- "Russia" section of "Literature" article in Britannica Book of the Year 2007, published by Encyclopædia Britannica, 2008, online version retrieved 14 January 2009

- Kishkovsky, Sophia, "Dmitry Prigov 1940–2007: A Russian poet and performance artist whose work was respected in the west", 27 July, 2007reprint of New York Times obituary; retrieved 14 January 2009

- Peter, Thomas, "Artists Mock Establishment With Sense of Absurd", Reuters article as printed in The Moscow Times, 24 July 2008, retrieved 14 January 2009

External links

- The End(s) of Russian Poetry: An Interview with Dmitry Prigov by Philip Metres

- Dimitry Alexandrovich Prigov, Soviet-Era Avant-Garde Poet and Artist, Rest in Peace an overview that includes some Prigov poems

- Russia’s leading conceptualist poet has died poet Ron Silliman provides a useful memento to Prigov, with links to pieces on Prigov, including Silliman's own blog-essay from 22 March 2006

- Biography of Dmitri Prigov (in English)

- Bibliography of poetry in English translation

- Prigov PennSound page with sound recording of "Alphabets"

- Prigov poems tr. into English at Jacket