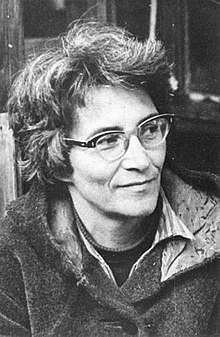

Tatyana Velikanova

Tatyana Mikhailovna Velikanova (Russian: Татья́на Миха́йловна Велика́нова, 3 February 1932 in Moscow – 19 September 2002 in Moscow) was a mathematician and Soviet dissident. A veteran of the human rights movement in the Soviet Union, she was an editor of A Chronicle of Current Events for most of that underground periodical's existence (1968-1983), bravely exposing her involvement with the anonymously edited and distributed bulletin at a press conference in May 1974.[1]

Tatyana M. Velikanova | |

|---|---|

Татьяна Михайловна Великанова | |

| |

| Born | 3 February 1932 |

| Died | 19 September 2002 (aged 70) |

| Citizenship | USSR, Russia |

| Alma mater | Moscow State University |

| Occupation | mathematician, teacher |

| Known for | human rights activism |

| Movement | dissident movement in the Soviet Union |

| Criminal charge(s) | Anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda (Article 70 of the RSFSR Criminal Code) |

| Criminal penalty | Four years in corrective-labour camps; five years internal exile. |

| Spouse(s) | Konstantin Babitsky |

She was also a founding member in 1969 of the Initiative Group on Human Rights in the USSR, the first human rights organization in the USSR since 1918. Arrested in November 1979, Velikanova was sentenced in August 1980[2] to four years in a prison camp and five years of internal exile. Turning down the offer of an amnesty from Mikhail Gorbachev in December 1987 as one of the last of two women convicted under Article 70 (the other was Elena Sannikova),[3] Velikanova voluntarily served her sentence of exile to the end.[4]

Biography

Born on 3 February 1932, Velikanova graduated from the Faculty of Mechanics and Mathematics of Moscow State University in 1954. A mathematician by training, she began work as a teacher in a school in the Urals. Then, from 1957 onwards, she was employed as a programmer in Moscow.[5]

The making of a dissident (1968–1969)

Velikanova became a dissident in 1968. That year she witnessed the 1968 Red Square demonstration, an open protest by seven people against the crushing of the Prague Spring reforms by the Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia.[4] She had gone to the Square with one of the demonstrators, her husband Konstantin Babitsky, so as to testify as a witness in court if needed. Like the other protestors Babitsky was arrested on the spot. He was sentenced to three years in exile in the Far Northern Komi Region.[5][6] Velikanova's experience at the trial where her testimony was distorted and used against Babitsky, led her to decide she would never again participate in such judicial proceedings.[6] (Nor did she, see below, when she was herself put on trial in 1980.)

In May 1969, with 14 other dissidents, Velikanova co-founded the Action Group for the Defense of Human Rights in the USSR.[7] Unusually for the dissident movement at the time, the organization tried to appeal to the international community. Speaking on behalf of the victims of political repression in the Soviet Union the Group wrote to the UN Commission on Human Rights.[8] (The appeal was almost instantly translated and republished in the West.[9]

In 1970, Velikanova began contributing to the samizdat periodical A Chronicle of Current Events.[10] The unofficial bi-monthly gathered reports from all over the USSR of violations by the Soviet authorities of civil rights and judicial procedure, and recorded the response to those violations. It soon became the principal uncensored Russian-language source of information about political repressions during Leonid Brezhnev's time as Party leader.[4][11] Velikanova eventually became one of its main organizers and editors.[12]:31–32

As the years passed similar journals came into existence in other Soviet republics, The Ukraine Herald and the Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania. Their information continued to flow to Moscow, however, for translation into Russian and inclusion in the Chronicle of Current Events.

Chronicle resumes publication (1974–1979)

In 1974, the KGB initiated a major crackdown on the bulletin, arresting several of its editors and distributors, threatening to make more arrests, regardless of authorship, for every published issue of the Chronicle.

In order to deflect pressure from other participants, and to stress that the Chronicle was in their view a legal publication, three of those involved decided to forsake anonymity. On 7 May, Tatyana Velikanova, Sergei Kovalev and Tatyana Khodorovich assumed public responsibility at a press conference in Moscow for the bulletin's future distribution. They then released three delayed issues, one for December 1972 and two covering 1973,[13] and a statement that "we regard it as our duty to facilitate as wide a circulation for [the Chronicle] as possible."[12]:32

Sergei Kovalev was arrested at the end of 1974 and given a long term of imprisonment and internal exile at his trial the next year; Tatyana Khodorovich emigrated from the USSR in 1977. In 1979, Velikanova along with Arina Ginzburg, Malva Landa, Viktor Nekipelov and Andrei Sakharov demanded a referendum in the Baltic States to allow them to determine their own political fate.[10] She was arrested that summer on charges of "anti-Soviet propaganda".[14] After her arrest, several prominent dissidents, among them Larisa Bogoraz, Elena Bonner, Sofiya Kalistratova and Lev Kopelev, formed a "Committee for the Defense of Velikanova". The Committee collected and disseminated information on her case in samizdat. A petition in defense of Velikanova was signed by almost five hundred people. Others who independently petitioned for her were Andrei Sakharov, the philosopher Grigory Pomerants, and the writer Vladimir Voinovich.[5]

Trial, sentence and return to Moscow (1980–1988)

At her trial in August 1980, Velikanova refused to defend herself[15], stating: "by participating in this trial, I would be collaborating in an unlawful act. I respect the law, and therefore, I refuse to take part in this trial."

When the verdict was handed down, Velikanova commented: "The farce is over. So that's that."[11]:81 She had been sentenced to four years in prison camp, followed by five years of exile.[4] Velikanova spent her camp term in Mordovia, east of Moscow, and in 1984 was sent into internal exile in western Kazakhstan.[4] An account of Velikanova's time in the Mordovian camps can be found in Grey Is the Color of Hope, written by fellow prisoner Irina Ratushinskaya.[16]

In December 1987 Gorbachev offered an amnesty to the last two women prisoners still serving a sentence under Article 70 (Anti-Soviet Agitation and Propaganda).Velikanova turned it down, demanding that she be rehabilitated and absolved of any crimes.[17]. Like a number of other political prisoners Velikanova refused to agree to such conditions, and she served her full term of exile.[11]:86

Documentary and death

In late 1989 Sergei Kovalyov, Tatiana Velikovanova and Alexander Lavut were interviewed about their dissident activities for the seven-part "Red Empire" TV series (Central TV), fronted by Robert Conquest.[18] Unfortunately, Granite Productions (CEO Simon Welfare, series director Gwyneth Hughes), the company which made the film, destroyed the tapes of this interview. Naturally, the recording ran for many minutes, and was much longer than the short excerpt which showed the three chatting round Alexander Lavut's kitchen table.

Kovalyov subsequently became a familiar figure on Russian TV as the country's first Human Rights Ombudsman and a member of successive convocations of parliament (Supreme Soviet, State Duma). Velikanova and Lavut lived the rest of their lives, known only to a few, and died in comparative obscurity. After her return to Moscow late in 1988, she took up work in the School 57, teaching math and Russian language and literature.[19] She died on 19 September 2002.[4]

References

- "To readers of the Chronicle", A Chronicle of Current Events (28.0), 31 December 1972 (May 1974).

- "The trial of Tatyana Velikanova", A Chronicle of Current Events (58.1), November 1980.

- "The release of political prisoners and the application of amnesties", USSR News Update (23-1), 15 December 1987 (in Russian).

- Kishkovsky, Sophia. "Tatyana M. Velikanova, 70, Soviet Human Rights Activist". New York Times., 17 October 2002.(Retrieved 14 August 2015.)

- "Алфавит инакомыслия. Великанова". svoboda.org (in Russian). 14 February 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ""Параллели, события, люди". Шестая серия. Татьяна Великанова". www.golos-ameriki.ru. Voice of America. 14 March 2014. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- "Tatyana Velikanova". The Times. 30 October 2002.

- "An Appeal to the UN Commission on Human Rights", A Chronicle of Current Events (8.10) 30 June 1969.

- Yakobson, Anatoly; Yakir, Pyotr; Khodorovich, Tatyana; Podyapolskiy, Gregory; Maltsev, Yuri; et al. (21 August 1969). "An Appeal to The UN Committee for Human Rights". The New York Review of Books.

- A Chronicle of Current Events (in English).

- Horvath, Robert (2005). "The rights-defenders". The Legacy of Soviet Dissent: Dissidents, Democratisation and Radical Nationalism in Russia. London; New York: RoutledgeCurzon. pp. 70–129. ISBN 9780203412855.

- Gilligan, Emma (2004). Defending Human Rights in Russia: Sergei Kovalyov, Dissident and Human Rights Commissioner, 1969–2003. London. ISBN 978-0415546119.

- A Chronicle of Current Events Nos 28–30, 31 December 1972 to 31 December 1973.

- A Chronicle of Current Events No 55, 31 December 1979 — 55.2 "Arrests".

- "The Trial of T. Velikanova", A Chronicle of Current Events (58.1), 30 October 1980.

- Ratushunskaya, Irina (1989). Grey Is the Color of Hope. Vintage International. ISBN 978-0-679-72447-6.

- "The release of political prisoners and the application of amnesties", USSR News Update (23-1), 15 December 1987 (in Russian).

- Part 7: Conclusion (1990). Red Empire. Yorkshire Television, 1990/Vestron Video, 1992. Produced and directed by Mike Dormer, Gwyneth Hughes, and Jill Marshall.

- https://dissidenten.eu/laender/russland/biografien/tatjana-welikanowa/

External links

- ""Алфавит инакомыслия". Великанова" ["Alphabet of dissent". Velikanova] (in Russian). Radio Liberty. 4 February 2012.

- Natella Boltyanskaya (14 March 2014). "Шестая серия. Татьяна Великанова" [The sixth part. Tatyana Velikanova]. Voice of America (in Russian). Parallels, Events, People.