American yellow warbler

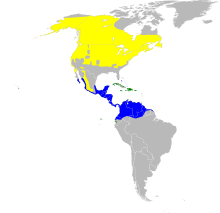

The yellow warbler (Setophaga petechia, formerly Dendroica petechia) is a New World warbler species. Yellow warblers are the most widespread species in the diverse genus Setophaga, breeding in almost the whole of North America, the Caribbean, and down to northern South America.

| Yellow warbler | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male in breeding plumage, Canada | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Parulidae |

| Genus: | Setophaga |

| Species: | S. petechia |

| Binomial name | |

| Setophaga petechia | |

| Subspecies | |

|

About 35 (but see text) | |

| |

| Distribution of the yellow warbler Breeding range Year-round range Wintering range | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Etymology

The genus name Setophaga is from Ancient Greek ses, "moth", and phagos, "eating", and the specific petechia is from Italian petecchia, a small red spot on the skin.[2] The American yellow warbler is sometimes colloquially called the "summer yellowbird".[3]

Description and taxonomy

Other than in male breeding plumage and body size, all warbler subspecies are very similar. Winter, female and immature birds all have similarly greenish-yellow uppersides and are a duller yellow below. Young males soon acquire breast and, where appropriate, head coloration. Females are somewhat duller, most notably on the head. In all, the remiges and rectrices are blackish olive with yellow edges, sometimes appearing as an indistinct wing-band on the former. The eyes and the short thin beak are dark, while the feet are lighter or darker olive-buff.[4][5]

The 35 subspecies of D. petechia can be divided into three main groups according to the males' head color in the breeding season.[5] Each of these groups is sometimes considered a separate species, or the aestiva group (yellow warbler) is considered a species different from D. petechia (mangrove warbler, including golden warbler); the latter option is the one currently accepted by the International Ornithological Congress World Bird List.[6]

Depending on subspecies, the American yellow warbler may be between 10 and 18 cm (3.9 and 7.1 in) long, with a wingspan from 16 to 22 cm (6.3 to 8.7 in). They weigh 7–25 g (0.25–0.88 oz), varying between subspecies and whether on migration or not, globally averaging about 16 g (0.56 oz) but only 9–10 g (0.32–0.35 oz) in most breeding adults of the United States populations. Among standard measurements throughout the subspecies, the wing chord is 5.5 to 7 cm (2.2 to 2.8 in), the tail is 3.9 to 5.6 cm (1.5 to 2.2 in), the bill is 0.8 to 1.3 cm (0.31 to 0.51 in) and the tarsus is 1.7 to 2.2 cm (0.67 to 0.87 in).[5] The summer males of this species are generally the yellowest warblers wherever they occur. They are brilliant yellow below and greenish-golden above. There are usually a few wide, somewhat washed-out rusty-red streaks on the breast and flanks. These markings are the reason for the scientific name petechia, which roughly translates to "liver spotted".[7] The subspecies in this group mostly vary in brightness and size according to Bergmann's and Gloger's Rule.[8]

The golden warbler (petechia group; 17 subspecies[5]) is generally resident in the mangrove swamps of the West Indies. Local seasonal migrations may occur. On the Cayman Islands for example, D. p. eoa was found to be "decidedly scarce" on Grand Cayman and apparently absent from Cayman Brac in November 1979, while it had been a "very common" breeder in the group some 10 years before, and not frequently seen in the winters of 1972/1973; apparently, the birds disperse elsewhere outside the breeding season. The Cuban golden warbler (D. p. gundlachi) barely reached the Florida Keys where it was first noted in 1941, and by the mid-20th century a breeding population was resident.[9] Though individual birds may stray farther north, their distribution is restricted by the absence of mangrove habitat.

They are generally smallish, usually weighing about 10 g (0.35 oz) or less and sometimes[10] as little as 6.5 g (0.23 oz). The summer males differs from those of the yellow warbler in that they have a rufous crown, hood or mask. The races in this group vary in the extent and hue of the head patch.

The mangrove warbler (erithachorides group; 12 subspecies[5]) tends to be larger than other yellow warbler subspecies groups, averaging 12.5 cm (4.9 in) in length and 11 g (0.39 oz) in weight. It is resident in the mangrove swamps of coastal Middle America and northern South America; D. p. aureola is found on the oceanic Galápagos Islands.[5] The summer males differ from those of the yellow warbler in having a rufous hood or crown. The races in this group vary in the extent and hue of the hood, overlapping extensively with the golden warbler group in this character.[5]

The American yellow warbler (aestiva group; 6 subspecies)[5] breeds in the whole of temperate North America as far south as central Mexico in open, often wet, woods or shrub. It is migratory, wintering in Central and South America. They are very rare vagrants to western Europe.[4]

- Resident adult male mangrove warbler, S. p. bryanti, Quepos, Costa Rica

Breeding male golden warbler, Washington-Slagbaai National Park, Bonaire, (Netherlands Antilles)

Breeding male golden warbler, Washington-Slagbaai National Park, Bonaire, (Netherlands Antilles)_-Santa_Cruz_-Puerto_Ayorto_c.jpg) Breeding male S. p. aureola mangrove warbler at Puerto Ayora, Santa Cruz (Galápagos Islands)

Breeding male S. p. aureola mangrove warbler at Puerto Ayora, Santa Cruz (Galápagos Islands) Breeding female Dendroica aestiva, Horicon Marsh, Wisconsin (United States)

Breeding female Dendroica aestiva, Horicon Marsh, Wisconsin (United States)- Yellow warbler S. p. gundlachi male resident, Cuba

Vocalizations

The song is a musical strophe that can be rendered sweet sweet sweet, I'm so sweet, although it varies considerably between populations. The call is a soft or harder chip or ship. This is particularly frequently given by females after a male has finished his song. In territorial defence, they give hissing calls, while seet seems to be a kind of specialized cowbird alert (see below). Other calls are given in communication between pair-members, neighbors, or by young begging for food. These birds also communicate with postures and perhaps with touch.[4]

Ecology

American yellow warblers breed in most of North America from the tundra southwards, except for the far Southwest and the Gulf of Mexico coast.[4] American yellow warblers winter to the south of their breeding range, from southern California to the Amazon region, Bolivia and Peru.[4] The mangrove and golden warblers occur to the south of it, to the northern reaches of the Andes.

American yellow warblers arrive in their breeding range in late spring – generally about April/May – and move to winter quarters again starting as early as July, as soon as the young are fledged. Most, however, stay a bit longer; by the end of August, the bulk of the northern populations has moved south, though some may linger almost until fall. At least in northern Ohio, yellow warblers do not linger, leaving as they did 100 years ago.[11]

The breeding habitat of American yellow warblers is typically riparian or otherwise moist land with ample growth of small trees, in particular willows (Salix). The other groups, as well as wintering birds, chiefly inhabit mangrove swamps and similar dense woody growth. Less preferred habitat are shrubland, farmlands and forest edges. In particular American yellow warblers will come to suburban or less densely settled areas, orchards and parks, and may well breed there. Outside the breeding season, these warblers are usually encountered in small groups, but while breeding they are fiercely territorial and will try to chase away any conspecific intruder that comes along.[4]

These birds feed mainly on arthropods, in particular insects. They acquire prey by gleaning in shrubs and on tree branches, and by hawking prey that tries to fly away. Other invertebrates and some berries and similar small juicy fruits[12] are also eaten, the latter especially by American yellow warblers in their winter quarters. The yellow warbler is one of several insectivorous bird species that reduce the number of coffee berry borer beetles in Costa Rica coffee plantations by 50%. Caterpillars are the staple food for nestlings, with some – e.g. those of geometer moths (Geometridae) – preferred over others.[13]

The predators of yellow and mangrove warblers are those – snakes, foxes, birds of prey, and many others – typical of such smallish tree-nesting passerines. The odds of an adult American yellow warbler to survive from one year to the next are on average 50%; in the southern populations, by contrast, about two-thirds of the adults survive each year. Conversely, less than one American yellow warbler nest in three on average suffers from predation in one way or another, while two out of three mangrove and golden warbler nests are affected.[14]

Snakes, including the blue racer (Coluber constrictor foxii) and common garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis),[15] are significant nest predators, taking nestlings and fledglings as well as sick or distracted adults. Likewise corvids such as the American crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos) and blue jay (Cyanocitta cristata),[16] and large climbing rodents, notably the American red squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus).[16] Carnivores, in particular members of the Musteloidea, including the striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis), long-tailed weasel (Mustela frenata) and common raccoon (Procyon lotor);[4] the red fox (Vulpes vulpes); and domestic or feral cats, are similarly opportunistic predators. All these pose little threat to the nimble, non-nesting adults, which are taken by certain smallish and agile birds such as the American kestrel (Falco sparverius) and Cooper's hawk (Accipiter cooperii), and the sharp-shinned hawk (A. striatus). Other avian predators of adults have included peregrine falcons (Falco peregrinus) and merlins (Falco columbarius). Owls such as great horned owls (Bubo virginianus) and eastern screech owls (Megascops asio) have been known to assault yellow warblers of all ages during night.[4][17]

These New World warblers seem to mob predators only rarely. An exception are cowbirds, which are significant brood parasites. The yellow warbler is a regular host of the brown-headed cowbird (Molothrus ater), with about 40% of all nests suffering attempted or successful parasitism. By contrast, the tropical populations are less frequent hosts to the shiny cowbird (M. bonariensis), with only 10% of nests affected. This may be due to the slightly larger size of shiny cowbirds, which are less likely to survive being feed by the much smaller warbler, compared to brown-headed cowbirds.[17] The yellow warbler is one of the few passerine proven to be able to recognize the presence of cowbird eggs in its nest.[17] Upon recognizing one the warbler will often smother it with a new layer of nesting material. It will usually not try to save any of its own eggs that have already been laid, but produce a replacement clutch. Sometimes, the parents desert a parasitized nest altogether and build a new one. Unlike some cuckoos, cowbird nestlings will not actively kill the nestlings of the host bird; mixed broods of Setophaga and Molothrus may fledge successfully.[14] However, success of fledging in yellow warbler nests is usually decreased by the parasitism of cowbirds due to the pressures of raising a much larger bird.[17]

Other than predation, causes of mortality are not well known. The maximum recorded ages[18] of wild yellow warblers are around 10 years. A wintering American yellow warbler examined near Turbo, Colombia was not infected with blood parasites, unlike other species in the study. It is unclear whether this significant, but wintering birds in that region generally lacked such parasites.[19]

Breeding

As usual for members of the Parulidae, yellow warblers nest in trees, building a small but very sturdy cup nest. Females and males rear the young about equally, but emphasize different tasks: females are more involved with building and maintaining the nest, and incubating and brooding the offspring. Males are more involved in guarding the nest site and procuring food, bringing it to the nest and passing it to the waiting mother, which does most of the actual feeding. As the young approach fledging, the male's workload becomes proportionally higher.[4]

The American yellow and mangrove (including golden) warblers differ in some other reproductive parameters. While the former is somewhat more of an r-strategist, the actual differences are complex and adapted to different environmental conditions. The yellow warbler starts breeding in May/June, while the mangrove warbler breeds all year round. American yellow warblers have been known to raise a brood of young in as little as 45 days, with 75 the norm. Tropical populations, by contrast, need more than 100 days per breeding. Males court the females with songs, singing 3,200 or more per day. They are, like most songbirds, generally serially monogamous; some 10% of mangrove warbler and about half as many American yellow warbler males are bigamous. Very few if any American yellow warblers breed more than once per year, with just 5% of female mangrove warblers doing so. If a breeding attempt fails, either parent will usually try to raise a second brood.[14]

The clutch of the American yellow warbler is 3–6 (typically 4–5, rarely 1–2) eggs. Incubation usually takes 11 days, sometimes up to 14. The nestlings weigh 1.3 g (0.046 oz) on average, are brooded for an average 8–9 days after hatching, and leave the nest the following day or the one thereafter. The mangrove warbler, on the other hand, has only 3 eggs per clutch on average and incubates some 2 days longer. Its average post-hatching brooding time is 11 days. Almost half of the parents (moreso in the mangrove warbler than the American yellow warbler) attend the fledglings for two weeks or more after these leave the nest. Sometimes the adults separate early, each accompanied by one to three of the young.[20]

Some 3–4 weeks after hatching, the young are fully independent of their parents. They become sexually mature at one year of age, and attempt to breed right away. Some 55% of all American yellow warbler nestings are successful in raising at least one young.[20] In contrast, only 25% of mangrove warbler nests successfully fledge any offspring, with accidents and predation frequently causing total loss of the clutch.

Status and conservation

Yellow warblers, in particular the young, devour many pest insects during the breeding season. The plumage and song of the breeding males have been described[4] as "lovely" and "musical", encouraging ecotourism. No significant negative effects of American yellow and mangrove warblers on humans have been recorded.[4]

Being generally common and occurring over a wide range, the yellow warbler is not considered a threatened species by the IUCN.[21] Some local decline in numbers has been found in areas, mainly due to habitat destruction and pollution. The chief causes are land clearance, the agricultural overuse of and herbicide and pesticide, and sometimes overgrazing. However, stocks will usually rebound quickly if riparian habitat is allowed to recover, particularly among the prolific American yellow warbler.[1][4]

The North American populations are legally protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. The Barbados golden warbler[22] (D. p. petechia) has been listed as "endangered foreign wildlife" by the United States' Endangered Species Act (ESA) since 1970; other than for specially permitted scientific, educational or conservation purposes, importing it into the USA is illegal. The Californian yellow warbler (D. p./a. brewsteri) and Sonoran yellow warbler (D.p./a. sonorana) are listed as "species of concern" by the ESA.[23]

Footnotes

- BirdLife International (2012). "Dendroica petechia". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 299, 355. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Grant, John Beveridge (1891). Our Common Birds and How to Know Them. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 112. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- Bachynski & Kadlec (2003)

- Curson et al. (1994)

- IOC World Bird List Family Parulidae

- Yezerinac, S. M., & Weatherhead, P. J. (1997). Extra–pair mating, male plumage coloration and sexual selection in yellow warblers (Dendroica petechia). Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 264(1381), 527-532.

- Bachynski & Kadlec (2003), AnAge (2009)

- Cunningham (1966)

- Olson et al. (1981)

- Henninger (1906), Bachynski & Kadlec (2003), OOS (2004)

- E.g. of Trophis racemosa (Moraceae): Foster (2007)

- Bachynski & Kadlec (2003), Foster (2007)

- Bachynski & Kadlec (2003), Salgado-Ortiz et al. (2008)

- E.g.Bachynski & Kadlec (2003)

- E.g. : Bachynski & Kadlec (2003)

- Lowther, P. E.; C. Celada; N. K. Klein; C. C. Rimmer & D. A. Spector. "Yellow Warbler- Birds of North America Online". The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 2013-12-13.

- "Average lifespan (wild) 131 months" in Bachynski & Kadlec (2003) is a lapsus

- Bachynski & Kadlec (2003), Londono et al. (2007), AnAge [2009]

- Bachynski & Kadlec (2003), Salgado-Ortiz et al. (2008), AnAge [2009]

- CITES and State of Michigan List listing are lapsus in Bachynski & Kadlec (2003)

- As "Barbados yellow warbler", but being the nominate subspecies it belongs to the golden/mangrove warbler group

- Bachynski & Kadlec (2003), USFWS (1970, 2009abc)

References

- AnAge [2009]: Dendroica petechia (sensu lato) life history data. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- Bachynski, K. & Kadlec, M. (2003): Animal Diversity Web – Dendroica petechia (sensu lato). Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- Cunningham, Richard L. (1966). "A Florida winter specimen of Dendroiva petechia gundlachi" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 78 (2): 232.

- Curson, Jon; Quinn, David & Beadle David (1994): New World Warblers. Christopher Helm, London. ISBN 978-0-7136-3932-2.

- Foster, Mercedes S. (2007). "The potential of fruiting trees to enhance converted habitats for migrating birds in southern Mexico". Bird Conservation International. 17 (1): 45–61. doi:10.1017/S0959270906000554.

- Henninger, W. F. (1906). "A preliminary list of the birds of Seneca County, Ohio" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 18 (2): 47–60.

- Londono, Aurora; Pulgarin-R., Paulo C.; Blair, Silva (2007). "Blood Parasites in Birds From the Lowlands of Northern Colombia" (PDF). Caribbean Journal of Science. 43 (1): 87–93.

- Ohio Ornithological Society (OOS) (2004): Annotated Ohio state checklist. Version of April 2004.

- Salgado-Ortiz, J.; Marra, P. P.; Sillett, T. S.; Robertson, R. J. (2008). "Breeding Ecology of the Mangrove Warbler (Dendroica petechia bryanti) and Comparative Life History of the Yellow Warbler Subspecies Complex". The Auk. 125 (2): 402–410. doi:10.1525/auk.2008.07012.

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) (1970): Conservation of Endangered Species and Other Fish or Wildlife. Federal Register 35(106): 8491–8498. PDF

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) [2009a]: Species Profile – Dendroica petechia brewsteri. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) [2009b]: Species Profile – Dendroica petechia petechia. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) [2009c]: Species Profile – Dendroica petechia sonorana. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

Further reading

- D. W. Snow (1966). "Annual cycle of the Yellow Warbler in the Galapagos". Bird-Banding. 37 (1): 44–49. doi:10.2307/4511232. JSTOR 4511232.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Setophaga aestiva. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Setophaga petechia |

- Mangrove warbler breeding ecology

- Yellow warbler species account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Yellow warbler – Dendroia petechia – USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Grizzlyrun.com Yellow warbler general information and photos

- Stamps at bird-stamps.org

- "Yellow warbler media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Yellow warbler photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)