Yeavering

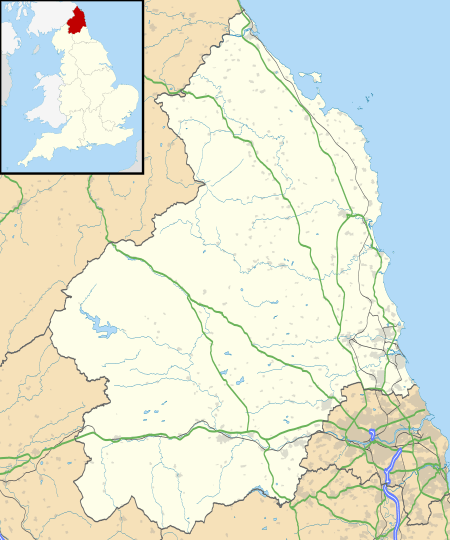

Yeavering (/ˈjɛvəriŋ/) is a very small hamlet in the north-east corner of the civil parish of Kirknewton in the English county of Northumberland. It is located on the River Glen at the northern edge of the Cheviot Hills. It is noteworthy as the site of a large Anglo-Saxon settlement that archaeologists have interpreted as being one of the seats of royal power held by the kings of Bernicia in the 7th century CE.

Evidence for human activity in the vicinity has been found from the Mesolithic, Neolithic and Bronze Age periods, although it would be in the Iron Age that significant settlement first occurred at Yeavering. In this period, a heavily inhabited hillfort was constructed on Yeavering Bell which appears to have been a major settlement centre at the time.

According to Book 2 Chapter 14 of the Ecclesiastical History of the Venerable Bede (680–735), in the year 627 Bishop Paulinus of York accompanied the Northumbrian king Edwin and his queen Æthelburg to their royal vill (the Latin term is villa regia), Adgefrin, where Paulinus spent 36 days preaching and baptising converts in the river Glen. The placename Gefrin, which is a Brittonic name meaning 'hill of the goats', survives as the modern Yeavering.

Landscape

Yeavering is situated at the western end of a valley known as Glendale, Northumberland, where the Cheviots foothills give way to the Tweed Valley, an area of fertile plain.[1] Yeavering's most prominent feature is the twin-peaked hill, Yeavering Bell (1158 feet/361 metres above sea level), which was used as a hillfort in the Iron Age. To the north of the Bell, the land drops off to a terrace 72 metres above sea level (usually known as the 'whaleback'), which is where the Anglo-Saxon settlement was located. The River Glen cuts through the whaleback, creating a relatively wide but shallow channel that lies 50 metres above sea level.[2] The Glen made large areas of neighbouring land around the whaleback waterlogged and boggy, and thereby difficult for human habitation, but modern drainage systems have largely removed this problem, simply leaving some marshy areas on the north and east sides of the Yeavering whaleback.[3]

Strong winds persistently blow through the area from a west or south-westerly direction, often reaching level 8 (gale) and sometimes 12 (hurricane force) on the Beaufort Scale.[4]

Prehistoric settlement

Mesolithic, Neolithic and Bronze Age settlement

Archaeological discoveries have shown that humans were living in the Glen Valley during the Mesolithic period. Such Mesolithic Britons were hunter-gatherers, moving around the landscape in small family or tribal groups in search of food and other natural resources. They made use of stone tools such as microliths, some of which have been found in the Glen Valley, indicating their presence during this period.[5]

In the later Neolithic and Bronze Age periods, humans living in Britain settled down in permanent communities and began farming to produce food. There is evidence of human activity in the valley dating from this period too, namely several 'ritual' pits and cremation burials.[5]

Iron Age and Romano-British settlement

The Yeavering site had seen human settlement before the Early Mediaeval period. The area was settled during the British Iron Age, when a hill fort was constructed on the Yeavering Bell hill. This fort was the largest of its kind in Northumberland, and had dry stone walls constructed around both of the Bell's peaks.[6] On the hill, over a hundred Iron Age roundhouses had been constructed, supporting a large local population.[7] The tribal group in the area was, according to later written sources, a group known as the Votadini.[6]

In the 1st century CE, southern and central Britain was invaded by the forces of the Roman Empire, who took this area under their dominion. The period of Roman occupation, known as Roman Britain or the Roman Iron Age, lasted until circa 410 CE, when the Roman armies and administration left Britain. Romano-British artefacts have also been found in relation to these roundhouses, including two late Roman minimi and several shards of Samian ware.[6]

Archaeologist Brian Hope-Taylor believed it likely that by the 1st century CE, the settlement at Yeavering Bell had become "a major political (tribal or sub-tribal) centre, either of the immediately surrounding area or of the whole region between the rivers Tyne and Tweed (in which there is no other monument of comparable character and size.)"[8]

Anglo-Saxon settlement

In the Early Mediaeval period, Yeavering was situated in the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Bernicia.[9]

Foundation

Archaeologist Brian Hope-Taylor believed that the monarchs of Bernicia had to rule over a kingdom in which there were populations belonging to two separate cultural and ethnic groups: the native Britons who were the descendants of the Romano-British population, and the Anglo-Saxons who were migrant colonists from continental Europe. He speculated that the Anglo-Saxon communities were primarily settled around the coastal areas of Bernicia, where trade and other links would have been going on with other Anglo-Saxon populations elsewhere in Britain. He argued that this was evidenced by the heavily Anglicised place name evidence in that area.[10] On the other hand, he thought that the British populations were larger in the central regions of Bernicia, where very few Anglo-Saxon artefacts have been discovered in Early Mediaeval burials. For this reason, he suspected that the Bernician rulers, in an attempt to administer both ethnic groups, decided to have two royal seats of government, one of which was at Bamburgh on the coast, and the other which was at Yeavering, which was in the British-dominated central area of their kingdom.[10]

Hope-Taylor also theorised that the Anglo-Saxon settlement at Yeavering had been situated there because the site had been important in the preceding Iron Age and Romano-British periods, and that its construction was therefore "a direct and deliberate reference to the traditional native institutions of the area."[8] Accompanying this symbolic reason for maintaining the seat of power in the vicinity, Hope-Taylor also noted that the area had some of the most easily cultivatable soil in the region, making it ideal for agriculture and the settlement of agricultural communities.[8]

Buildings

There were a series of timber buildings constructed on the site that were excavated by archaeologists in the mid 20th century.

Building A1 was initially a "plain, aisled hall, devoid of annexes" which had a doorway situated on every wall. It was a large building, with wall timbers that were 5.5 to 6 inches thick set in trenches that varied from between 36 and 42 inches deep. After burning down in a fire, it was rebuilt "more robustly and precisely", with additional eastern and western annexes being added. Excavators found that daub had apparently been used on the walls, being plastered on to the timber. This too burned down at some point, following which a third version of Building A1 was erected, containing only one annexe, on the eastern side. This final building would in time come to rot away where it stood.[11]

Building A2 was a Great Hall with partitioning palisades that created ante-chambers at its two ends. Rather than being destroyed in a fire, it is apparent that the building was intentionally demolished most likely because "in a new phase of construction" at the site, "it had ceased to be useful."[12] Archaeological excavators discovered that this building had been built on top of an earlier prehistoric burial pit.[13] Building A3 was also a Great Hall, and resembled a "larger and more elaborate version" of the second construction of Building A1. It was apparently destroyed in a fire, before being rebuilt and although some repairs were made in subsequent years, it gradually decayed in situ.[14] Building A4 was similar to A2 in most respects, but had only one partition, located on its eastern end.[15] However, Building A5 differed from these Great Halls, being described as "a house or even a cottage" by Hope-Taylor, and it apparently had a door on each of its walls.[16] Buildings A6 and A7 were identified as being older than A5, but were of a similar size.[17] Building B was another hall, this time with a western annexe.[18]

Building C1 was a rectangular pit, leading archaeologists to speculate that it was the site of a water tank or cistern, and the presence of a layer of white ash led them to surmise that it had burnt down.[19] Building C2 was another rectangular building like most of those at Yeavering, and had four doors, although unlike many of the others showed no evidence of having been damaged or destroyed by fire.[20] Building C3 was also a rectangular timber hall, although was larger than C2 and was of "unusual construction", having double rows of external post-holes.[21] Building C4 was the largest hall in this group, having seen two structural phases, the former of which had apparently been heavily damaged or destroyed by fire.[22]

Building D1 was described by Hope-Taylor as being an example of "strange incompetence" due to the various mistakes that apparently occurred during its construction. Although likely intended to be rectangular, from the post hole evidence it is apparent that the finished result was rhomboidal, and it appears that not long after construction, the building collapsed or was demolished, to be replaced by another hall, which also exhibited various structural problems such as wonky walls.[23]

Building D2 was designed as "the exact counterpart of Building D1 in size, form and orientation", and the two were positioned in a precise alignment. It was however at some point demolished, and a new "massive and elaborate" version was built in its place.[24] Building D2 has been widely interpreted as a temple or shrine room dedicated to one or more of the gods of Anglo-Saxon paganism, making it the only known example of such a site yet found by archaeologists in England.[25][26] Archaeologists came to this conclusion due to the complete lack of any objects associated with normal domestic use, such as a scatter of animal bones of broken pot sherds. Accompanying this was a large pit filled with animal bones, the majority of which were oxen skulls.[27]

Building E was situated in the centre of the township, and consisted of nine foundation trenches that were each concentric in shape. From the positioning, depth and width of the post holes, the excavators came to the conclusion that the building was a large tiered seating area facing a platform that may have carried a throne.[28]

There is also a feature referred to as the Great Enclosure by Hope-Taylor, consisting of a circular earthwork with an entrance at the southern end. In the middle of this enclosure was a rectangular timber building, known as Building BC, which the excavators believed was contemporary with the rest of the enclosure.[29]

Burials

An Anglo-Saxon burial dated to the early 7th century, known as Grave AX, was found located amidst the buildings at Yeavering. Hope-Taylor characterised it as "one of the strangest and most interesting minor features of the site" and it contained the diffuse outline of an adult body which had been interned in an east-west alignment. Various oxidised remnants of what were originally metal objects were found with the body, as was the remnants of a goat skull, which had been positioned to face eastward.[30] Further examining the metal objects located in the grave, Hope-Taylor came to the conclusion that one of them, a seven-foot long bronze-bound wooden pole, was most likely a staff or perhaps standard used for ceremonial purposes.[31]

Archaeologists have also identified a series of graves at the eastern end of the site, leading them to refer to this area as the Eastern Cemetery. Hope-Taylor's team identified these burials as having undergone five separate phases, indicating that it had been used for a relatively long time.[32]

Bede's account

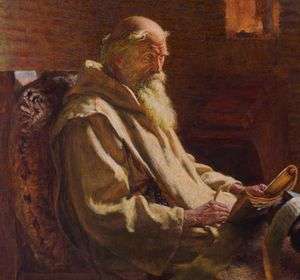

One of the best sources of information that contemporary historians have about the Anglo-Saxon period of English history are the records made by an Anglo-Saxon monk named Bede (672/673-735) who lived at the monastery in Jarrow. Considered to be "the Father of English History", Bede wrote a number of texts dealing with the Anglo-Saxon migration and conversion, most notable the Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of the English People), completed circa 731 and divided up into various books. It was in the second book of the Historia ecclesiastica that Bede mentioned a royal township, Ad Gefrin, which he located as being at a point along the River Glen.[33] He described how King Edwin of Bernicia, shortly after converting to Christianity, brought a Christian preacher named Paulinas to his royal township at Ad Gefrin where the priest proceeded to convert the local people from their original pagan religion to Christianity. This passage goes thus:

- So great was then the fervour of the faith [Christianity], as is reported and the desire of the washing of salvation among the nation of the Northumbrians, that Paulinas at a certain time coming with the king and queen to the royal country-seat, which is called Ad Gefrin, stayed with them thirty-six days, fully occupied in catechising and baptising; during which days, from morning till night, he did nothing else but instruct the people resorting from all villages and places, in Christ's saving word; and when instructed, he washed them with the water of absolution in the river Glen which is close. This town, under the following kings, was abandoned, and another was built instead of it, at the place called Melmin.[34]

Archaeologist Brian Hope-Taylor believed that it was "beyond reasonable doubt" that Yeavering was indeed Bede's Ad Gefrin.[35]

Excavations by Brian Hope-Taylor

The components of the site, as revealed by the cropmarks and Hope-Taylor's excavations, are:

- A double-palisaded enclosure, the Great Enclosure, on the terrace edge at the east end of the complex. This was not a fortification in a military sense but acted as a meeting place or cattle corral.

- A sequence of rectangular buildings west of the Great Enclosure (Area A) with massive foundation trenches (in some cases, more than two metres deep). Four buildings in the set (A2, A4, A3a, A3b) had floor areas of up to about 300 square metres. Hope-Taylor called these Great Halls.

- A set of nine concentric foundation trenches west of the set of halls, whose outline forms a wedge shape. Hope-Taylor interpreted this as a tiered auditorium with a capacity to seat some three hundred people.

- Other rectangular buildings, broadly similar to the first set of Great Halls though smaller, at the west end of the site (Area D) and to the north (Area C).

- Inhumation burials at the east and west ends of the site including, among these, graves set into already-existing prehistoric burial monuments, the Eastern and Western Ring Ditches.

These, then, are the principal features of this royal palace; and it is the buildings which have attracted most attention in secondary literature, as royal halls of the sort which the poet of Beowulf had in mind when he wrote of Heorot, the hall of King Hrothgar. Typically the halls are rectangular buildings, massive in construction with (in A4, for example) square-section timbers of 140mm placed upright side-by-side along the wall lines; twice as long as their width, arranged as a single large room or, sometimes, with a small space partitioned off at one or both ends. In the later stages (A3a and A3b) annexes appear at the ends and the interior space becomes divided into rooms. Here then, at Yeavering, was demonstrated the reality of the poet's creation. The buildings were constructed to high standards, with timbers carefully measured and shaped to standard sizes. Hope-Taylor argued that a standard unit of measurement was employed in the buildings and also in the overall lay-out of the site. The 'Yeavering foot' (300 mm) was slightly shorter than the modern imperial unit.

Hope-Taylor understood Yeavering as a place of contact between an indigenous British population and an incoming Anglian elite, few in number: an Anglo-British centre, as he expressed it in his monograph title. He developed this view from the complex archaeological stratification which, he judged, could not be compressed into the seventh century but which implied a much longer period of use at the site. This led him to a wider thesis on the origins of the kingdom of Bernicia. The then current view (as expressed, for instance, in the final (1971) edition of Sir Frank Stenton's Anglo-Saxon England) was that the early Bernician kings were hemmed into their coastal stronghold at Bamburgh by aggressive British neighbours until Æthelfrith (592–616) succeeded in overcoming the Britons and expanding the kingdom. Yeavering convinced Hope-Taylor that the Bernician kings had developed interests inland from Bamburgh through peaceful collaboration with the Britons at an earlier date. The archaeological underpinning of this thesis has three elements:

- The building sequence at Yeavering showed a progression from a British style of building with walls of post-and-panel construction, through to a hybrid style which drew on both continental Germanic traditions and those of Roman Britain. The solid, load-bearing walls of his Styles II, III, and IV, he termed ‘Yeavering Style’.

- The burials show a continuity of ritual tradition from the Bronze Age through to the 7th century.

- The Great Enclosure, which in its most developed state took the form of a double palisade, had evolved through a series of palisades constructed according to local traditions. Its first stage was the earliest feature of the site and, as such, it gave a link with the old tribal centre on Yeavering Bell.

No other structure comparable to the auditorium has been observed in post-Roman Britain and Hope-Taylor suggested that its affinities lay with the Roman world; it was a realisation in timber (the normal building material of Germanic Europe) of the architecture of the Roman theatre, with the wedge shape being one segment of the theatre's semi-circular form. Roman influence, or an evocation of Roman forms, was evident also in the render which was applied to the outer surfaces of the walls of the principal halls.

In Building D2a, one of the group of buildings at the west end of the site, cattle bones were piled up alongside one wall in a way which led the excavator to suggest that this was a temple, used in cult practice. Numerous inhumation burials occupied the site, and amongst them, the grave of a child, tightly trussed up in foetal position. The body occupied only half of the grave area, while in the other half was placed a cow's tooth, another hint of cult practice involving cattle. A grave on the threshold of the Great Hall A4 contained a goat's skull which might indicate another animal cult associated with the name of the place, the goat's hill. The two prehistoric burial monuments which were already on the site, the Western and Eastern Ring Ditches were brought back into use. The centre of each was marked with a post (a totem pole) and burials were set out around these. Some of the burials are undoubtedly of pagan tradition, but Yeavering runs into the Christian era: Bede’s text is the narrative of a conversion episode in 627. It is suggested that the refurbishment of the ‘temple’ building D2a (re-built in the same position as D2b) was a Christianisation as recommended by Pope Gregory I (see Bede's Ecclesiastical History, Book 1 Chapter 30). Building B, associated with the cemetery, was initially interpreted as a church. However, this has since been criticised on the basis that burials did not become associated with churches until the 9th century, and building B is thought to be earlier than this. An alternative explanation since offered is that this was a building dedicated not to worship, but to mortuary preparations.

The chronology for the excavated features is not securely established. Hope-Taylor found few closely datable objects (a belt-buckle of 570/80 – 630/40 and a coin 630/40) and there are no radiocarbon dates. He constructed a relative sequence for the site from the stratigraphic connections for the Area A complex and the Great Enclosure and he drew other areas of the site into this scheme through a typology of building styles. He established a fixed chronology for the scheme by arguing that a fire which destroyed the Great Hall A4, the auditorium and other buildings was the result of an attack following the death of King Edwin in 633. A later fire is attributed to an attack by Penda, King of Mercia, in the 650s. The set of four Great Halls of Area A, which are shown by excavation to have succeeded one after another, are judged to be the halls of four successive kings, Æthelfrith (592–616), Edwin (616–633), Oswald (635–642) and Oswiu (642–670) (numbers A2, A4, A3a and A3b respectively). Critics have noted that there is no confirmation in written records that Yeavering was sacked in 633 or the 650s. It would be reasonable to say that Hope-Taylor's chronology is a working construct founded on secure stratigraphic sequences and extended beyond that.

Scholarly critique

Critical commentary on Yeavering since Hope-Taylor has challenged some of his ideas and developed his thoughts in other respects. Two elements of his culture contact thesis (the Anglo-British centre) have come under review.

First, the buildings. Roger Miket (1980) questioned the identity of the Style I post-and-panel buildings (A5, A6, A7, D6) as British and then Christopher Scull (1991) developed a more extensive critique of Phase I: the post-and-panel buildings are much like those from Anglo-Saxon settlements anywhere else in England. Hope-Taylor gives them a date around 550 but there is no reason why they should not be much nearer 600, and therefore in an Anglo-Saxon cultural context. Hope-Taylor pushes them back to 550 to accommodate the needs of the building typology which he has constructed, which calls for a Style II (D1a, D1b, D2a) to intervene before Style III which begins with D2b and Æthelfrith's Great Hall A2. This leads to what might be called a minimalist view, as articulated recently by Tim Gates (2005), which sees the site originating as an ordinary Anglian farming settlement of the sixth century, subsequently elaborated.

Second, the burials. Richard Bradley (1987) drew on ideas developed in social anthropology to argue that the claim for ritual continuity cannot be sustained, depending as it does on treating as equivalents the linear time of an historical era (the Early Medieval) and the ritual time of prehistory. In place of a literal, chronological continuity, he proposed the idea of a 'creation of continuity' (akin, perhaps, to Eric Hobsbawn's idea of the 'invention of tradition') to suggest that the burials in the Eastern and Western Ring Ditches are a deliberate re-use (long after the original use) of these features as a strategy by a new elite group to appropriate to themselves the ideological power held in the memory of the traditional burial places. This use of burial practice is comparable, Bradley suggests, with the way in which Anglo-Saxon royal houses developed for themselves genealogies which showed their descent from the god Woden.

The Great Enclosure, the third element supporting the culture contact idea, has been less closely studied, despite the fact that for Hope-Taylor this was the first feature on the site, beginning when a Romano-British field system went out of use. Tim Gates (2005) has shown that there was no field system but that Hope-Taylor misunderstood some periglacial features which he interpreted as field boundaries. Colm O'Brien (2005) has analysed the stratigraphic linkages of the Great Enclosure, showing, in the light of the arguments of Scull and Gates, how uncertain is the chronology of this feature. In one comment, Hope-Taylor compared the Great Enclosure to a Scandinavian Thing, or folk meeting place and behind this lies the idea that the Great Enclosure carries forward into the Early Medieval era functions of assembly which had once belonged at the hillfort on Yeavering Bell. Thanks to recent the field survey by Stuart Pearson (1998; and see also Oswald and Pearson 2005) the stages of development of this hillfort and its 105 house-foundations are accurately defined, but it remains unclear when it was occupied and what role, if any, it had during the Roman Iron Age.

Hope-Taylor's thesis on culture contact can no longer be held in the terms in which he expressed it but Leslie Alcock (1988) has shown how a number of sites associated with Northumbrian kings in the 7th and 8th centuries, Yeavering among them, developed from earlier defended centres in what is now northern England and southern Scotland (England and Scotland had not at that time come into being as separate states). Similarly, Sam Lucy (2005) looked to the tradition of long cist burials in Scotland for affinities with those at Yeavering, as Hope-Taylor had done. So, as archaeological studies have developed, the idea that some aspects of Yeavering can be placed within a northern tradition has gained support.

In the first detailed study of the Auditorium since Hope-Taylor's, Paul Barnwell (2005) was persuaded of Hope-Taylor's understanding of its structure and also of its reference to the Roman world; the theatres is an instrument of Roman provincial governance rather than imperial presence. Barnwell has considered how the structure might be used in formal administrative functions and suggests that for these it draws upon practice from the Frankish world.

Paul Barnwell's analysis moves beyond the study of structure, phasing and chronology which have been the concern of much of the scholarship around Yeavering to a consideration of how a structure was used. Carolyn Ware (2005) has proposed a similar sort of approach to study of the Great Halls through an examination of openness and seclusion and of sight lines within the buildings. Together, these studies begin to suggest how a king may present himself at this place and how the architectural structures allow for formal behaviour and ceremonial.

The question of how Yeavering functioned in relation to its hinterland has been considered by Colm O'Brien (2002). The Latin term villa regia, which Bede used of the site, suggests an estate centre as the functional heart of a territory held in the king's demesne. The territory is the land whose surplus production is taken into the centre as food render to support the king and his retinue on their periodic visits as part of a progress around the kingdom. Other estates in the territory, such as nearby Thirlings, whose central settlement has been excavated (O'Brien and Miket 1991), stand in a relationship of dependency to the central estate, bound by obligations of service. This territorial model, known as a multiple estate or shire has been developed in a range of studies and O'Brien, in applying this to Yeavering, has proposed a geographical definition of the wider shire of Yeavering and also a geographical definition of the principal estate whose structures Hope-Taylor excavated.

Summary – the present state of knowledge

While there are still some large questions to resolve on matters of chronology, Yeavering offers a number of insights into the nature of early Northumbrian kingship. It sits within the wider Germanic tradition of a life centred around the hall and its occupants drew upon forms, practices and ideas from the Roman and Frankish worlds. But at the same time it drew on local, regional traditions for structures and in burial rites. Its importance for the Northumbrian kings was, perhaps, as the traditional place of local assembly and as a cult centre at which deep-rooted, traditional ideologies could be appropriated. It is not clear why it was abandoned: Bede says that it was replaced by Maelmin. This site is known from cropmarks at Milfield a few kilometres north-east (Gates and O'Brien 1988). Perhaps, as Rosemary Cramp suggested (1983), as the Northumbrian kings gained in authority they had no need of the traditional assembly and cult site in the hills.

The Gefrin Trust

In April 2000 archaeologist Roger Miket returned to north Northumberland after sixteen years living on Skye. While in Sale and Partners, an estate agent in Wooler, the secretary, knowing Roger's interest in the history of the area, informed him of their recent instruction to handle the sale of 'a funny bit of land at Yeavering with a history!'

The 'funny bit of land' was, in fact, the site of Ad Gefrin.

Northumberland County Council, Northumberland National Park and a number of private bidders all showed an interest in the site but the final successful bidder was Roger.

Roger's initial aim was to place the management of the site on an even footing before transferring ownership to an independent charitable trust. When this was in place Roger began contacting interested experts for guidance on the best way to establish the Gefrin Trust. It was decided that the trust should be made up from representatives of local government, English Heritage and the academic world with the ability to co-opt other members to address specific needs and issues should they arise. Community involvement was considered very important.

From its initial meeting in the spring of 2004 the trust has met every four months to discuss progress, planning and the way forward for the site.

Trust members are:

- Professor Rosemary Cramp (Chairperson)

- Roger Miket (Secretary)

- Dr Christopher Burgess (Northumberland County Council)

- Paul Frodsham (Archaeologist)

- Tom Johnston (Glendale Gateway Trust)

- Brian Cosgrove (Education and Media)

Co-opted:

- Kate Wilson (English Heritage)

- Chris Gerrard (Durham University)

Public access to the palace site has been granted. The site has been re-fenced and the stone walls have been repaired. New gates, kissing gates and paths have been installed to improve access, and information panels have been set up. The trust have entered a ten-year partnership agreement with DEFRA and now hold a 999-year lease for the site and all management decisions affecting it.

The magnificent goat-head gateposts and other carvings you will see today at the site are the work of local Northumbrian artist Eddie Robb. As well as the goat heads you can find a carving of the head of a Saxon warrior and representations of the 'Bamburgh Beast'. They are very much in the style and spirit of the illustrations done by Brian Hope-Taylor himself in the pages of his book Yeavering, An Anglo-British centre of early Northumbria.

The Trust has a website, www.gefrintrust.org, which gives news and information on the work it is currently undertaking in areas such as geophysical prospecting to identify additional structures at the site, new aerial photographs of the site (including some spectacular LIDAR imagery), and new work on the finds from Hope-Yaylor's excavation, thought lost but recently rediscovered following his death. The television programme made by Brian Hope-Taylor as part of The Lost Centuries series in which he describes the site in its wider context is available on the website for viewing, as well as access to a number of PDF downloads on publications about the site, including Brian Hope-Taylor's full excavation report, Yeavering; an Anglo-British Centre of Early Northumbria (1977; available through the kindness of English Heritage), a guide to a recent exhibition on new work undertaken by the Trust, as well as other specialist articles on aspects of the site. Also considerable information is to be found on Gefrin.com, maintained and developed voluntarily for the trust by Brian Cosgrove as the main information point for the project. This allows the Gefrin Trust website to concentrate on reporting news, comments and decisions relevant to the Trust.

The Trust organised the first Open Days at the site in June 2007. The main purpose, in the words of archaeologist Roger Miket, is simply to "create a presence for these two days and be on hand to meet and greet anyone who might wish to come to the site. We will also be there to demonstrate and explain how remote-sensing works, as well as carry out guided tours of the site. On the Sunday we are also offering a guided walk up Yeavering Bell."

Archaeological investigation

During the early 20th century, the University of Cambridge's Curator of Aerial Photography, Dr John Kenneth Sinclair St Joseph (then in the midst of photographing the Roman forts of northern England), flew over Yeavering and photographed a series of crop marks produced in local oat fields during a particularly severe drought.[36]

In 1951, the archaeologist Brian Hope-Taylor examined these aerial photographs to determine whether they could show the 7th century royal township described by Bede as Ad Gefrin. He decided that they probably did, and set about planning to excavate at the site.[37] Whilst he began to approach government bodies for funding, the site itself came under threat in 1952 from nearby quarrying on its south-western side, but was saved when Sir Walter de L. Aitchison informed St Joseph, who had risen to the position of Chief Inspector of Ancient Monuments at the Ministry of Works. St Joseph stepped in to protect the site, allowing Hope-Taylor to open up excavations in 1953.[38] His first excavations came to an end in 1957, when the landowner found that he could no longer afford to let the site be left agriculturally unproductive. He returned to re-excavate at the site from 1960 to 1962.[35]

Yeavering in popular culture

As an important centre of Anglo-Saxon royalty about which a lot of information is known, Yeavering occurs as a location in several books set in the Early Middle Ages.

In Ragnarok by Anne Thackery, set from the time of Ida of Bernicia to that of Aethelfrith of Northumbria, Yeavering is rarely mentioned save as the base of one of Ida's brothers. From the context the book would seem to refer to Yeavering Bell rather than the villa regis.

The Month of Swallows by C.P.R. Tisdale is set in the time of the conversion of Edwin of Northumbria. Gefrin is one of several settings which are visited regularly by the peripatetic court. It is held by Eanfrið son of Æðelfrið as a sworn vassal of Edwin and is also home to his sister Æbbe, later famous as the abbess of Coldingham.

Kathryn Tickell composed an instrumental piece called "Yeavering" inspired by Yeavering Bell, which appears on The Kathryn Tickell Band's 2007 album 'Yeavering'[39]

See also

- History of Northumberland

- Northumbria

- Battle of Humbleton Hill

- Wooler

- Edwin of Northumbria

- Paulinus of York

- Battle of Yeavering

References

Footnotes

- Hope-Taylor 1977. p. 05.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. pp. 06 and 09.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. p. 11.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. p. 15.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. p. 20.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. p. 06.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. pp. 06–07.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. p. 17.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. p. 16.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. pp. 26–27.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. pp. 49–50.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. pp. 51–53.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. p. 53.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. p. 55.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. pp. 60–62.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. pp. 62–63.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. p. 63.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. pp. 73–78.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. pp. 88–90.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. p. 91.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. pp. 91–92.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. pp. 92–94.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. pp. 95–96.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. p. 97.

- Branston 1957. p. 25.

- Wilson 1992. pp. 45–47.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. pp. 98–102.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. pp. 119–121.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. p. 78-88.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. p. 67-69.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. pp. 200–201.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. Pp. 70–73.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. p. 01.

- Bede c.731. Book II, Chapter XIV.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. p. xvii.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. p. 04.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. pp. 04–05.

- Hope-Taylor 1977. pp. xvii and 05.

- Strange, Philip (15 August 2015). "THE MUSIC OF PLACE, THE PLACE OF NATURE". Philip Strange Science and Nature Writing. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

Bibliography

- Historical texts

- Excavation report

- Hope-Taylor, Brian (1977). Yeavering: An Anglo-British centre of early Northumbria. London: Her Majesty's Stationery. ISBN 0-11-670552-3.

- Pearson S (1998) Yeavering Bell Hillfort, Northumberland. English Heritage: Archaeological Investigation Report Series AI/3/2001.

- Academic books

- Branston, Brian (1957). The Lost Gods of England. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Wilson, David (1992). Anglo-Saxon Paganism. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-01897-8.

- Alcock L (1988) Bede, Eddius and the Forts of the North Britons. Jarrow: Jarrow Lecture.

- Barnwell P (2005) Anglian Yeavering: a continental perspective. 174–184 in Frodsham and O’Brien (eds).

- Bradley R (1987) Time Regained: the creation of continuity. Journal of the British Archaeological Association 140, 1–17.

- Cramp R (1983) Anglo-Saxon Settlement. 263-97 in J C Chapman and H Mytum (eds) Settlement in North Britain 1000BC – AD1000. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports

- Frodsham P and O'Brien C (eds) (2005) Yeavering: people, power, place. Stroud: Tempus Publishing

- Gates T (2005) Yeavering and Air Photography: discovery and interpretation. 65–83 in Frodsham and O’Brien (eds).

- Gates T and O’Brien C (1988) Cropmarks at Milfield and New Bewick and the Recognition of Grubenhauser in Northumberland. Archaeologia Aeliana 5th Series, 16, 1–10.

- Lucy S (2005) Early Medieval Burial at Yeavering: a retrospective. 127–144 in Frodsham and O’Brien (eds).

- Miket R (1980) A Re-statement of Evidence from Bernician Burials. 289–305 in P. Rahtz, T. Dickinson and L. Watts (eds) Anglo-Saxon Cemeteries 1979. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports.

- O’Brien C (2002) The Early Medieval Shires of Yeavering, Bamburgh and Breamish. Archaeologia Aeliana 5th Series, 30, 53–73.

- O’Brien C (2005) The Great Enclosure. 145–152 in Frodsham and O’Brien (eds).

- O’Brien C and Miket R (1991) The Early Medieval Settlement of Thirlings. Durham Archaeological Journal 7, 57–91.

- Oswald A and Pearson S (2005) Yeavering Bell Hillfort. 98–126 in Frodsham and O’Brien.

- Scull C (1991) Post-Roman Phase 1 at Yeavering: a reconsideration. Medieval Archaeology 35, 51–63.

- Stenton F (1971) Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Clarendon Press

- Ware C (2005) The Social Use of Space at Gefrin. 153–160 in Frodsham and O’Brien (eds).

External links

![]()