Yama-uba

Yamauba (山姥 or 山うば), Yamamba or Yamanba are variations[1] on the name of a yōkai[2] found in Japanese folklore.

Description

They can also be written as 山母, 山姫, or 山女郎, and in the town of Masaeki, Nishimorokata District, Miyazaki Prefecture (now Ebino), a "yamahime" would wash her hair and sing in a lovely voice. Deep in the mountains of Shizuoka Prefecture, there is a tale that the "yamahime" would appear as a woman around twenty years of age and would have beautiful features, a small sleeve, and black hair, and that when a hunter encounters her and tries to shoot at it with a gun, she would repel the bullet with her hands. In Hokkaido, Shikoku, and the southern parts of Kyushu, there is also a yamajijii (mountain old man), and the yamauba would also appear together with a yamawaro (mountain child), and here the yamauba would be called "yamahaha" (mountain mother) and the yamajijii a "yamachichi" (mountain father). In Iwata District, Shizuoka Prefecture, the "yamababa" that would come and rest at a certain house was a gentle woman that wore clothes made of a tree's bark. She borrowed a cauldron to boil some rice, but the cauldron would become full with just two go of rice. There wasn't anything unusual about it, but it was said that when she sat to the side of it, the floor would creak. In Hachijō-jima, a "dejji" or "decchi" would perform kamikakushi by making people walk around places that should not exist for an entire night, but if one becomes friendly with her, she would lend you lintel, among other things. Sometimes she would also nurse children who go missing for three days. It is said that there are splotches on her body and she has her breasts attached to her shoulders as if there was a tasuki cord. In the Kagawa Prefecture, yamauba within rivers are called "kawajoro" (river lady),[3] and whenever a dike is about to break due to a great amount of water, she would say in a loud weeping voice, "My house is going to be washed away."[4] In Kumakiri, Haruno, Shūchi District, Shizuoka Prefecture (now Hamamatsu), there are legends of a yamauba called "hocchopaa", and it would appear in mountain roads during the evening. Mysterious phenomena, such as the sounds of festivals and curses coming from the mountains, were considered to be because of this hocchopaa.[5] In the Higashichikuma District, Nagano Prefecture, they are called "uba", and the legends there tell of a yokai with long hair and one eye,[6] and from its name, it is thought to be a kind of yamauba.[7]

In the tales, the ones that were attacked by yamauba were typically travelers and merchants, such as ox-drivers, horse-drivers, coopers, and notions keepers, who often walk along mountain paths and encounter people in the mountains, so they are thought to be the ones who had spread such tales.

Yamauba have been portrayed in two different ways. There were tales where men stocking ox with fish for delivery encountered yamauba at capes and got chased by them, such as the Ushikata Yamauba and the Kuwazu Jobo, as well as a tale where someone who was chased by the yamauba would climb a chain appearing from the skies in order to flee, and when the yamauba tried to make chase by climbing the chain too, she fell to her death into a field of buckwheat, called the "Tendo-san no Kin no Kusari." In these tales, the yamauba was a fearful monster trying to eat humans. On the other hand, there were tales such as the Nukafuku Komefuku (also called "Nukafuku Kurifukk"), where two sisters out gathering fruit met a yamauba who gave treasure to the kind older sister (who was tormented by her stepmother) and gave misfortune to the ill-mannered younger sister. There is also the "ubakawa" tale, where a yamaba would give a human good fortune. In Aichi Prefecture, there is a legend that a house possessed by a yamauba would quickly gain wealth and fortune, and some families have deified them as protective gods.

Appearance

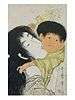

Depending on the text and translator, the Yamauba appears as a monstrous crone, "her unkempt hair long and golden white ... her kimono filthy and tattered",[8] with cannibalistic tendencies.[9] In one tale a mother traveling to her village is forced to give birth in a mountain hut assisted by a seemingly kind old woman, only to discover, when it is too late, that the stranger is actually Yamauba, with plans to eat the helpless Kintarō.[10] In another story the yōkai raises the orphan hero Kintarō, who goes on to become the famous warrior Sakata no Kintoki.[11]

Yamauba is said to have a mouth at the top of her head, hidden under her hair.[12] In one story it is related that her only weakness is a certain flower containing her soul.[13]

.jpg)

Noh drama

In one Noh drama, translated as, Yamauba, Dame of the Mountain, Konparu Zenchiku states the following:

- Yamauba is the fairy of the mountains, which have been under her care since the world began. She decks them with snow in winter, with blossoms in spring ... She has grown very old. Wild white hair hangs down her shoulders; her face is very thin. There was a courtesan of the Capital who made a dance representing the wanderings of Yamauba. It had such success that people called this courtesan Yamauba though her real name was Hyakuma.[14]

The play takes place one evening as Hyakuma is traveling to visit the Zenko Temple in Shinano, when she accepts the hospitality of a woman who turns out to be none other than the real Yamauba, herself.[14]

Western literature

Steve Berman's short story, “A Troll on a Mountain with a Girl”[15] features Yamauba.

Lafcadio Hearn, writing primarily for a Western audience, tells a tale like this:

- Then [they] saw the Yama-Uba,—the "Mountain Nurse." Legend says she catches little children and nurses them for awhile, and then devours them. The Yama-Uba did not clutch at us, because her hands were occupied with a nice little boy, whom she was just going to eat. The child had been made wonderfully pretty to heighten the effect. The spectre, hovering in the air above a tomb at some distance ... had no eyes; its long hair hung loose; its white robe floated light as smoke. I thought of a statement in a composition by one of my pupils about ghosts: "Their greatest peculiarity is that they have no feet." Then I jumped again, for the thing, quite soundlessly, but very swiftly, made through the air at me.[8]

See also

- Baba Yaga, a similar character to Yama-uba, in Russian folklore.

Notes

- Cavallaro, 132.

- Joly, 396.

- 武田明. "四国民俗 通巻10号 仲多度郡琴南町美合の聞書". 怪異・妖怪伝承データベース. 国際日本文化研究センター. Retrieved 2009-08-17.

- 村上健司編著 (2000). 妖怪事典. 毎日新聞社. pp. 124頁. ISBN 978-4-620-31428-0.

- 加藤恵 (1989). "県別日本妖怪事典". In 野村敏晴編 (ed.). 歴史読本 臨時増刊 特集 異界の日本史 鬼・天狗・妖怪の謎. 新人物往来社. pp. 319頁.

- 日野巌 (2006). "日本妖怪変化語彙". 動物妖怪譚. 中公文庫. 下. 中央公論新社. pp. 236頁. ISBN 978-4-12-204792-1.

- 妖怪事典. pp. 55頁.

- Hearn, 267.

- Ashkenazi, 294.

- Ozaki, 70.

- Ozaki, 67.

- Shirane, 558.

- Monaghan, 238.

- Waley, 247.

- Wallace, 184.

References

- Ashkenazi, Michael. Handbook of Japanese mythology. ABC-CLIO (2003)

- Cavallaro, Dani. The Fairy Tale and Anime: Traditional Themes, Images and Symbols at Play on Screen. McFarland. (2011)

- Hearn, Lafcadio. Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan. Houghton, Mifflin and company. (1894)

- Joly, Henri. Legend in Japanese art: a description of historical episodes, legendary characters, folk-lore, myths, religious symbolism, illustrated in the arts of old Japan. New York: J. Lane. (1908)

- Monaghan, Patricia. Encyclopedia of goddesses and heroines. ABC-CLIO. (2010)

- Ozaki, Yei Theodora. The Japanese fairy book. Archibald Constable & Co. (1903)

- Shirane, Haruo. Early Modern Japanese Literature: An Anthology, 1600-1900. Columbia University Press. (2004)

- Waley, Arthur. The Nō plays of Japan. New York: A. A. Knopf (1922)

- Wallace, Sean. Japanese Dreams. Lethe Press. (2009)