Richborough Castle

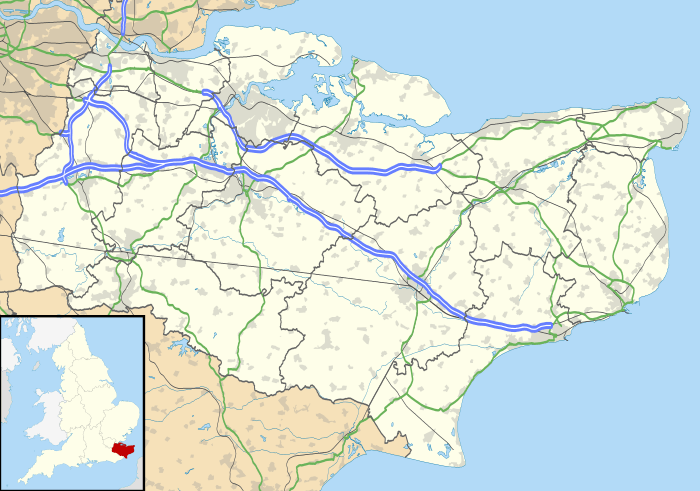

Richborough Castle contains the ruins of a Roman Saxon Shore fort, collectively known as Richborough Fort or Richborough Roman Fort. It is situated in Richborough near Sandwich, Kent, in the United Kingdom.

| Richborough Castle | |

|---|---|

Rutupiæ | |

| Richborough, Kent in England | |

Richborough Roman Fort | |

Richborough Castle | |

| Coordinates | 51.294°N 1.332°E |

| Grid reference | TR324602 |

| Type | Roman fort |

Rutupiae or Portus Ritupis was founded by the Romans after their invasion of Britain in AD 43. Because of its position near the mouth of the Stour, Rutupiae was the major British port under the Romans and the starting point for the road now known as Watling Street. Additional routes connected Durovernum (Canterbury) with further ports at Dubris (Dover), Lemanis (Lympne), and Regulbium (Reculver). Earth fortifications were first dug on the site in the 1st century, probably as a storage depot and bridgehead for the Roman army. This transformed into a civilian and commercial town, which was later replaced by a Saxon Shore fort around the year 277. The later fort is believed to have been constructed by the rebel Carausius.[1] The site is now under the care of English Heritage.

Etymology

The meaning of the name Rutupiae is uncertain, although the first element may derive from the British Celtic *rutu- meaning "rust; mud" (cf. Welsh rhwd). An alternative attested name for the fort, Ritupiae, may represent a clearer British form, containing the word *ritus "ford" (Welsh rhyd), referring to a crossing point between the then island and the mainland. The meaning of the -piae element remains unknown.

History

Roman Invasion

It has commonly been accepted that Richborough Castle was the landing site for the Claudian invasion in 43 AD. This is because of the existence of mid-1st century ditches and fortifications on the site, and because such a crossing would have exploited the shortest route over the English Channel. The ditches and fortifications are assumed to have been built to protect the Roman bridgehead and supply depot. However, explicit details on the site of the Claudian invasion have not survived and its location is a matter of scholarly debate.

Civilian town

As the fighting moved north, Rutupiae became an increasingly large civilian settlement. There were temples, an amphitheatre (visible as a hummock in the grass 5 minutes' walk from the main site), and a mansio (first built in 100, it was a building that went through several phases, being a guest house for visiting officials, bath house and administration building).

As a port, the town always competed with Portus Dubris (modern Dover), about 15 mi (24 km) south along the coast. However, Richborough was widely regarded throughout the Roman Empire for the quality of its oysters. They are mentioned as on a par with those from the Italian Lucrine Lake in Juvenal.[2] "Rutupine shore" was used as a common metonymy for Britain in Latin writers.[3]

Triumphal arch

A major quadrifrons triumphal arch was erected straddling Watling Street, the main road from Richborough to London. Its position and size suggest it may have been built to celebrate the final conquest of Britain after Agricola’s victory at the Battle of Mons Graupius.[4] Almost 25 m (82 ft) high, it had a facade of high quality, Italian granite. Standing as it did between the port and the province, passage through the arch signified formal entry into Britannia (cf the similarly maritime Arch of Trajan at Ancona). Only the foundations and mound of the Richborough arch are still visible. It was demolished by the Romans themselves, apparently to provide building materials for the later Saxon Shore fort on the site.

Saxon Shore fort

.jpg)

During the late 3rd century this (by now large) civilian town was remilitarized by its conversion into a Saxon Shore fort. The Saxon Shore forts were a series of forts built by the Romans along the Channel on the English and French sides to guard against invading Saxon pirates. Construction of the fort here is believed to have started in 277 and completed in 285. This involved the demolition and reuse as spolia of the triumphal arch, and numismatic evidence suggests it occurred during the reign of Carausius.[1]

The fort was 5 acres (2.0 ha) in area and was surrounded by massive walls, forming an almost perfect square. However, the north and south walls were constructed differently. The north wall was built by separate gangs of laborers, while the south wall seems to have been built as a single unit. This suggests that the north wall of the fort was built sometime after the construction of the south wall. In some places, the walls reached over 25 feet (8 m) in height, and were built of small ashlar and double-tile courses. The main entrance of the fort was in the west wall. The walls stand to a great height and were of such high quality that they only recently needed repointing.

Though some stone buildings existed in the interior of the fort, most of its buildings were made of timber. There existed a central rectangular building built of stone, which was probably the principia (headquarters). Small, stone-built baths were also present at Richborough.[5]

Church at Richborough

There exists an unexplained structure at Richborough that is believed to be a font. Today, this structure is almost entirely destroyed. The hexagonal font discovered during the excavations at Richborough suggests that baptisms could have been a function of this church. The church was probably built at the end of the 4th century or at the beginning of the 5th century. It seems plausible that the church was built of wood.[6]

Roman withdrawal

During the decline of the Roman Empire, Richborough was eventually abandoned by the Romans and after this, the site was occupied by a Saxon religious settlement.

Excavations

Excavations carried out in late 2008 of a 90 m (300 ft) section of Roman wall uncovered the original Roman coastline along with the remains of a medieval dock. The discovery and excavation of the beach itself has pinpointed its geographical relationship to the site's earthworks, proving that the earthworks were a beachhead defence, protecting around 700 m (2,300 ft) of coast. The site is now two and half miles inland from the current coastline.[7][8] In 2020, excavations by English Heritage were to have explored the amphitheatre. Senior Properties Historian Paul Pattison explained that the investigation was to find out "what did the amphitheatre look like, how was it constructed and what happened after it fell out of use?".[9]

References

- White, Donald. Litus Saxonicum; The British Saxon Shore in Scholarship and History, page 36. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin for Dept. of History, University of Wisconsin, 1961.

- Satires 4.141.

- p. 39, Victoria County History of Kent: Romano-British Kent, 1932. Retrieved on 10 May 2007

- Stillwell, Richard; William Lloyd MacDonald; Marian Holland McAllister (1976). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton University Press. p. 778. Retrieved 10 May 2007.

- Johnson, J.S. (1970). "The Date of the Construction of the Saxon Shore Fort at Richborough". Britannia. Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies. 1: 240–248. doi:10.2307/525843. JSTOR 525843.

- Brown, P.D.C (1971). "The Church at Richborough". Britannia. Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies. 2: 225–231. doi:10.2307/525812. JSTOR 525812.

- BBC News - Dig Uncovers Roman Invasion Coast.

- The Independent - Roman Invasion Beach Found In Kent.

- "Archaeologists to dig up secrets of Roman amphitheatre in Kent". The Guardian. 9 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rutupiæ. |

- Richborough Roman Fort page at English Heritage

- 'Gateway to Britannia' on Google Arts & Culture