Word processor (electronic device)

A word processor is an electric device or computer software application that performs the task of composing, editing, formatting, and printing of documents.

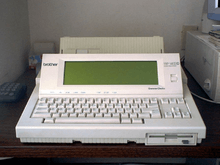

The word processor was a stand-alone office machine in the 1960s, combining the keyboard text-entry and printing functions of an electric typewriter with a recording unit, either tape or floppy disk (as used by the Wang machine) with a simple dedicated computer processor for the editing of text.[1] Although features and designs varied among manufacturers and models, and new features were added as technology advanced, the first word processors typically featured a monochrome display and the ability to save documents on memory cards or diskettes. Later models introduced innovations such as spell-checking programs, and improved formatting options.

As the more versatile combination of personal computers and printers became commonplace, and computer software applications for word processing became popular, most business machine companies stopped manufacturing dedicated word processor machines. As of 2009 there were only two U.S. companies, Classic and AlphaSmart, which still made them.[2] Many older machines, however, remain in use. Since 2009, Sentinel has offered a machine described as a "word processor", but it is more accurately a highly specialised microcomputer used for accounting and publishing.[3]

Word processing was one of the earliest applications for the personal computer in office productivity, and was the most widely used application on personal computers until the World Wide Web rose to prominence in the mid-1990s.

Although the early word processors evolved to use tag-based markup for document formatting, most modern word processors take advantage of a graphical user interface providing some form of what-you-see-is-what-you-get ("WYSIWYG") editing. Most are powerful systems consisting of one or more programs that can produce a combination of images, graphics and text, the latter handled with type-setting capability. Typical features of a modern word processor include multiple font sets, spell checking, grammar checking, a built-in thesaurus, automatic text correction, web integration, HTML conversion, pre-formatted publication projects such as newsletters and to-do lists, and much more.

Microsoft Word is the most widely used word processing software according to a user tracking system built into the software. Microsoft estimates that roughly half a billion people use the Microsoft Office suite,[4] which includes Word. Many other word processing applications exist, including WordPerfect (which dominated the market from the mid-1980s to early-1990s on computers running Microsoft's MS-DOS operating system, and still (2014) is favored for legal applications), Apple's Pages application, and open source applications such as OpenOffice.org Writer, LibreOffice Writer, AbiWord, KWord, and LyX. Web-based word processors such as Office Online or Google Docs are a relatively new category.

Characteristics

Word processors evolved dramatically once they became software programs rather than dedicated machines. They can usefully be distinguished from text editors, the category of software they evolved from.[5][6]

A text editor is a program that is used for typing, copying, pasting, and printing text (a single character, or strings of characters). Text editors do not format lines or pages. (There are extensions of text editors which can perform formatting of lines and pages: batch document processing systems, starting with TJ-2 and RUNOFF and still available in such systems as LaTeX, as well as programs that implement the paged-media extensions to HTML and CSS). Text editors are now used mainly by programmers, website designers, computer system administrators, and, in the case of LaTeX, by mathematicians and scientists (for complex formulas and for citations in rare languages). They are also useful when fast startup times, small file sizes, editing speed, and simplicity of operation are valued, and when formatting is unimportant. Due to their use in managing complex software projects, text editors can sometimes provide better facilities for managing large writing projects than a word processor.[7]

Word processing added to the text editor the ability to control type style and size, to manage lines (word wrap), to format documents into pages, and to number pages. Functions now taken for granted were added incrementally, sometimes by purchase of independent providers of add-on programs. Spell checking, grammar checking and mail merge were some of the most popular add-ons for early word processors. Word processors are also capable of hyphenation, and the management and correct positioning of footnotes and endnotes.

More advanced features found in recent word processors include:

- Collaborative editing, allowing multiple users to work on the same document.

- Indexing assistance. (True indexing, as performed by a professional human indexer, is far beyond current technology, for the same reasons that fully automated, literary-quality machine translation is.)

- Creation of tables of contents.

- Management, editing, and positioning of visual material (illustrations, diagrams), and sometimes sound files.

- Automatically managed (updated) cross-references to pages or notes.

- Version control of a document, permitting reconstruction of its evolution.

- Non-printing comments and annotations.

- Generation of document statistics (characters, words, readability level, time spent editing by each user).

- "Styles", which automate consistent formatting of text body, titles, subtitles, highlighted text, and so on.

Later desktop publishing programs were specifically designed with elaborate pre-formatted layouts for publication, offering only limited options for changing the layout, while allowing users to import text that was written using a text editor or word processor, or type the text in themselves.

Typical usage

Word processors have a variety of uses and applications within the business world, home, education, journalism, publishing, and the literary arts.

Use in business

Within the business world, word processors are extremely useful tools. Some typical uses include: creating legal documents, company reports, publications for clients, letters, and internal memos. Businesses tend to have their own format and style for any of these, and additions such as company letterhead. Thus, modern word processors with layout editing and similar capabilities find widespread use in most business.

Use in home

While many homes have a word processor on their computers, word processing in the home tends to be educational, planning or business related, dealing with school assignments or work being completed at home. Occasionally word processors are used for recreational purposes, e.g. writing short stories, poems or personal correspondence. Some use word processors to create résumés and greeting cards, but many of these home publishing processes have been taken over by web apps or desktop publishing programs specifically oriented toward home uses. The rise of email and social networks has also reduced the home role of the word processor as uses that formerly required printed output can now be done entirely online.

History

Word processors are descended from the Friden Flexowriter, which had two punched tape stations and permitted switching from one to the other (thus enabling what was called the "chain" or "form letter", one tape containing names and addresses, and the other the body of the letter to be sent). It did not wrap words, which was begun by IBM's Magnetic Tape Selectric Typewriter (later, Magnetic Card Selectric Typewriter).

IBM Selectric

Expensive Typewriter, written and improved between 1961 and 1962 by Steve Piner and L. Peter Deutsch, was a text editing program that ran on a DEC PDP-1 computer at MIT. Since it could drive an IBM Selectric typewriter (a letter-quality printer), it may be considered the first-word processing program, but the term word processing itself was only introduced, by IBM's Böblingen Laboratory in the late 1960s.

In 1969, two software based text editing products (Astrotype and Astrocomp) were developed and marketed by Information Control Systems (Ann Arbor Michigan).[8][9][10] Both products used the Digital Equipment Corporation PDP-8 mini computer, DECtape (4” reel) randomly accessible tape drives, and a modified version of the IBM Selectric typewriter (the IBM 2741 Terminal). These 1969 products preceded CRT display-based word processors. Text editing was done using a line numbering system viewed on a paper copy inserted in the Selectric typewriter.

Evelyn Berezin invented a Selectric-based word processor in 1969, and founded the Redactron Corporation to market the $8,000 machine.[11] Redactron was sold to Burroughs Corporation in 1976.[12]

By 1971 word processing was recognized by the New York Times as a "buzz word".[13] A 1974 Times article referred to "the brave new world of Word Processing or W/P. That's International Business Machines talk ... I.B.M. introduced W/P about five years ago for its Magnetic Tape Selectric Typewriter and other electronic razzle-dazzle."[14]

IBM defined the term in a broad and vague way as "the combination of people, procedures, and equipment which transforms ideas into printed communications," and originally used it to include dictating machines and ordinary, manually operated Selectric typewriters.[15] By the early seventies, however, the term was generally understood to mean semiautomated typewriters affording at least some form of editing and correction, and the ability to produce perfect "originals". Thus, the Times headlined a 1974 Xerox product as a "speedier electronic typewriter", but went on to describe the product, which had no screen,[16] as "a word processor rather than strictly a typewriter, in that it stores copy on magnetic tape or magnetic cards for retyping, corrections, and subsequent printout".[17]

Mainframe systems

In the late 1960s IBM provided a program called FORMAT for generating printed documents on any computer capable of running Fortran IV. Written by Gerald M. Berns, FORMAT was described in his paper "Description of FORMAT, a Text-Processing Program" (Communications of the ACM, Volume 12, Number 3, March, 1969) as "a production program which facilitates the editing and printing of 'finished' documents directly on the printer of a relatively small (64k) computer system. It features good performance, totally free-form input, very flexible formatting capabilities including up to eight columns per page, automatic capitalization, aids for index construction, and a minimum of nontext [control elements] items." Input was normally on punched cards or magnetic tape, with up to 80capital letters and non-alphabetic characters per card. The limited typographical controls available were implemented by control sequences; for example, letters were automatically converted to lower case unless they followed a full stop, that is, the "period" character. Output could be printed on a typical line printer in all-capitals — or in upper and lower case using a special ("TN") printer chain — or could be punched as a paper tape which could be printed, in better than line printer quality, on a Flexowriter. A workalike program with some improvements, DORMAT, was developed and used at University College London.

Electromechanical paper-tape-based equipment such as the Friden Flexowriter had long been available; the Flexowriter allowed for operations such as repetitive typing of form letters (with a pause for the operator to manually type in the variable information),[18] and when equipped with an auxiliary reader, could perform an early version of "mail merge". Circa 1970 it began to be feasible to apply electronic computers to office automation tasks. IBM's Mag Tape Selectric Typewriter (MT/ST) and later Mag Card Selectric (MCST) were early devices of this kind, which allowed editing, simple revision, and repetitive typing, with a one-line display for editing single lines.[19] The first novel to be written on a word processor, the IBM MT/ST, was Len Deighton's Bomber, published in 1970.[20]

Effect on office administration

The New York Times, reporting on a 1971 business equipment trade show, said

- The "buzz word" for this year's show was "word processing", or the use of electronic equipment, such as typewriters; procedures and trained personnel to maximize office efficiency. At the IBM exhibition a girl typed on an electronic typewriter. The copy was received on a magnetic tape cassette which accepted corrections, deletions, and additions and then produced a perfect letter for the boss's signature ...[13]

In 1971, a third of all working women in the United States were secretaries, and they could see that word processing would affect their careers. Some manufacturers, according to a Times article, urged that "the concept of 'word processing' could be the answer to Women's Lib advocates' prayers. Word processing will replace the 'traditional' secretary and give women new administrative roles in business and industry."[13]

The 1970s word processing concept did not refer merely to equipment, but, explicitly, to the use of equipment for "breaking down secretarial labor into distinct components, with some staff members handling typing exclusively while others supply administrative support. A typical operation would leave most executives without private secretaries. Instead one secretary would perform various administrative tasks for three or more secretaries."[21] A 1971 article said that "Some [secretaries] see W/P as a career ladder into management; others see it as a dead-end into the automated ghetto; others predict it will lead straight to the picket line." The National Secretaries Association, which defined secretaries as people who "can assume responsibility without direct supervision", feared that W/P would transform secretaries into "space-age typing pools". The article considered only the organizational changes resulting from secretaries operating word processors rather than typewriters; the possibility that word processors might result in managers creating documents without the intervention of secretaries was not considered—not surprising in an era when few managers, but most secretaries, possessed keyboarding skills.[14]

Dedicated models

In 1972, Stephen Bernard Dorsey, Founder and President of Canadian company Automatic Electronic Systems (AES), introduced the world’s first programmable word processor with a video screen. The real breakthrough by Dorsey’s AES team was that their machine stored the operator’s texts on magnetic disks. Texts could be retrieved from the disks simply by entering their names at the keyboard. More importantly, a text could be edited, for instance a paragraph moved to a new place, or a spelling error corrected, and these changes were recorded on the magnetic disk.

The AES machine was actually a sophisticated computer that could be reprogrammed by changing the instructions contained within a few chips.[22][23]

In 1975, Dorsey started Micom Data Systems and introduced the Micom 2000 word processor. The Micom 2000 improved on the AES design by using the Intel 8080 single-chip microprocessor, which made the word processor smaller, less costly to build and supported multiple languages.[24]

Around this time, DeltaData and Wang word processors also appeared, again with a video screen and a magnetic storage disk.

The competitive edge for Dorsey's Micom 2000 was that, unlike many other machines, it was truly programmable. The Micom machine countered the problem of obsolescence by avoiding the limitations of a hard-wired system of program storage. The Micom 2000 utilized RAM, which was mass-produced and totally programmable.[25] The Micom 2000 was said to be a year ahead of its time when it was introduced into a marketplace that represented some pretty serious competition such as IBM, Xerox and Wang Laboratories.[26]

In 1978, Micom partnered with Dutch multinational Philips and Dorsey grew Micom's sales position to number three among major word processor manufacturers, behind only IBM and Wang.[27]

Software models

In the early 1970s, computer scientist Harold Koplow was hired by Wang Laboratories to program calculators. One of his programs permitted a Wang calculator to interface with an IBM Selectric typewriter, which was at the time used to calculate and print the paperwork for auto sales.

In 1974, Koplow's interface program was developed into the Wang 1200 Word Processor, an IBM Selectric-based text-storage device. The operator of this machine typed text on a conventional IBM Selectric; when the Return key was pressed, the line of text was stored on a cassette tape. One cassette held roughly 20 pages of text, and could be "played back" (i.e., the text retrieved) by printing the contents on continuous-form paper in the 1200 typewriter's "print" mode. The stored text could also be edited, using keys on a simple, six-key array. Basic editing functions included Insert, Delete, Skip (character, line), and so on.

The labor and cost savings of this device were immediate, and remarkable: pages of text no longer had to be retyped to correct simple errors, and projects could be worked on, stored, and then retrieved for use later on. The rudimentary Wang 1200 machine was the precursor of the Wang Office Information System (OIS), introduced in 1976. It was a true office machine, affordable by organizations such as medium-sized law firms, and easily learned and operated by secretarial staff.

The Wang was not the first CRT-based machine nor were all of its innovations unique to Wang. In the early 1970s Linolex, Lexitron and Vydec introduced pioneering word-processing systems with CRT display editing. A Canadian electronics company, Automatic Electronic Systems, had introduced a product in 1972, but went into receivership a year later. In 1976, refinanced by the Canada Development Corporation, it returned to operation as AES Data, and went on to successfully market its brand of word processors worldwide until its demise in the mid-1980s. Its first office product, the AES-90,[28] combined for the first time a CRT-screen, a floppy-disk and a microprocessor,[22][23] that is, the very same winning combination that would be used by IBM for its PC seven years later. The AES-90 software was able to handle French and English typing from the start, displaying and printing the texts side-by-side, a Canadian government requirement. The first eight units were delivered to the office of the then Prime Minister, Pierre Elliot Trudeau, in February 1974. Despite these predecessors, Wang's product was a standout, and by 1978 it had sold more of these systems than any other vendor.[29]

The phrase "word processor" rapidly came to refer to CRT-based machines similar to the AES 90. Numerous machines of this kind emerged, typically marketed by traditional office-equipment companies such as IBM, Lanier (marketing AES Data machines, re-badged), CPT, and NBI.[30] All were specialized, dedicated, proprietary systems, priced around $10,000. Cheap general-purpose computers were still for hobbyists.

Some of the earliest CRT-based machines used cassette tapes for removable-memory storage until floppy diskettes became available for this purpose - first the 8-inch floppy, then the 5¼-inch (drives by Shugart Associates and diskettes by Dysan).

Printing of documents was initially accomplished using IBM Selectric typewriters modified for ASCII-character input. These were later replaced by application-specific daisy wheel printers, first developed by Diablo, which became a Xerox company, and later by Qume. For quicker "draft" printing, dot-matrix line printers were optional alternatives with some word processors.

WYSIWYG models

Electric Pencil, released in December 1976, was the first word processor software for microcomputers.[31][32][33][34][35] Software-based word processors running on general-purpose personal computers gradually displaced dedicated word processors, and the term came to refer to software rather than hardware. Some programs were modeled after particular dedicated WP hardware. MultiMate, for example, was written for an insurance company that had hundreds of typists using Wang systems, and spread from there to other Wang customers. To adapt to the smaller, more generic PC keyboard, MultiMate used stick-on labels and a large plastic clip-on template to remind users of its dozens of Wang-like functions, using the shift, alt and ctrl keys with the 10 IBM function keys and many of the alphabet keys.

Other early word-processing software required users to memorize semi-mnemonic key combinations rather than pressing keys labelled "copy" or "bold". (In fact, many early PCs lacked cursor keys; WordStar famously used the E-S-D-X-centered "diamond" for cursor navigation, and modern vi-like editors encourage use of hjkl for navigation.) However, the price differences between dedicated word processors and general-purpose PCs, and the value added to the latter by software such as VisiCalc, were so compelling that personal computers and word processing software soon became serious competition for the dedicated machines. Word processing became the most popular use for personal computers, and unlike the spreadsheet (dominated by Lotus 1-2-3) and database (dBase) markets, WordPerfect, XyWrite, Microsoft Word, pfs:Write, and dozens of other word processing software brands competed in the 1980s; PC Magazine reviewed 57 different programs in one January 1986 issue.[32] Development of higher-resolution monitors allowed them to provide limited WYSIWYG—What You See Is What You Get, to the extent that typographical features like bold and italics, indentation, justification and margins were approximated on screen.

The mid-to-late 1980s saw the spread of laser printers, a "typographic" approach to word processing, and of true WYSIWYG bitmap displays with multiple fonts (pioneered by the Xerox Alto computer and Bravo word processing program), PostScript, and graphical user interfaces (another Xerox PARC innovation, with the Gypsy word processor which was commercialised in the Xerox Star product range). Standalone word processors adapted by getting smaller and replacing their CRTs with small character-oriented LCD displays. Some models also had computer-like features such as floppy disk drives and the ability to output to an external printer. They also got a name change, now being called "electronic typewriters" and typically occupying a lower end of the market, selling for under $200 USD.

During the late 1980s and into the 1990s the predominant word processing program was WordPerfect.[36] It had more than 50% of the worldwide market as late as 1995, but by 2000 Microsoft Word had up to 95% market share.[37]

MacWrite, Microsoft Word, and other word processing programs for the bit-mapped Apple Macintosh screen, introduced in 1984, were probably the first true WYSIWYG word processors to become known to many people until the introduction of Microsoft Windows. Dedicated word processors eventually became museum pieces.

See also

- Amstrad PCW

- Authoring systems

- Canon Cat

- Comparison of word processors

- Content management system

- CPT Word Processors

- Document collaboration

- List of word processors

- IBM MT/ST

- Microwriter

- Office suite

- TeX

- Typography

Literature

- Matthew G. Kirschenbaum Track Changes - A Literary History of Word Processing Harvard University Press 2016 ISBN 9780674417076

References

- "TECHNOWRITERS" Popular Mechanics, June 1989, pp. 71-73.

- Mark Newhall, Farm Show

- StarLux Illumination catalog

- "Microsoft Office Is Right at Home". Microsoft. January 8, 2009. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

- "InfoWorld Jan 1 1990". January 1990.

- Reilly, Edwin D. (2003). Milestones in Computer Science and Information Technology. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 256. ISBN 9781573565219.

- UNIX Text Processing, O'Reilly.

Nonetheless, the text editors used in program development environments can provide much better facilities for managing large writing projects than their office word-processing counterparts.

- "Information Control Systems Inc. (ICS) | Ann Arbor District Library".

- "Secretaries Get a Computer of their Own to Automate Typing" (PDF). Computers and Automation. January 1969. p. 59. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- "Computer Aided Typists Produce Perfect Copies". Computer World. November 13, 1968. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- Pozzi, Sandro (12 December 2018). "Muere Evelyn Berezin, creadora del primer procesador digital de textos" [Evelyn Berezin dies, creator of the first digital text processor]. El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 12 December 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

Berezin diseñó el primer sistema central de reservas de United Airlines cuando trabajaba para Teleregister y otro similar para gestionar la contabilidad de la banca a nivel nacional. En 1968 empezó a trabajar en la idea de un ordenador que procesara textos, utilizando pequeños circuitos integrados. Al año decidió dejar la empresa para crear la suya propia, que llamó Redactron Corporation.

- McFadden, Robert D. (2018-12-10). "Evelyn Berezin, 93, Dies; Built the First True Word Processor". The New York Times. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

- Smith, William D. (October 26, 1971). "Lag Persists for Business Equipment". The New York Times. p. 59.

- Dullea, Georgia (February 5, 1974). "Is It a Boon for Secretaries—Or Just an Automated Ghetto?". The New York Times. p. 32.

- "IBM Adds to Line of Dictation Items". The New York Times. September 12, 1972. p. 72. reports introduction of "five new models of 'input word processing equipment', better known in the past as dictation equipment" and gives IBM's definition of WP as "the combination of people, procedures, and equipment which transforms ideas into printed communications". The machines described were of course ordinary dictation machines recording onto magnetic belts, not voice typewriters.

- Miller, Diane Fisher (1997) "My Life with the Machine": "By Sunday afternoon, I urgently want to throw the Xerox 800 through the window, then run over it with the company van. It seems that the instructor forgot to tell me a few things about doing multi-page documents ... To do any serious editing, I must use both tape drives, and, without a display, I must visualize and mentally track what is going onto the tapes."

- Smith, William D. (October 8, 1974). "Xerox Is Introducing a Speedier Electric Typewriter". The New York Times. p. 57.

- O'Kane, Lawrence (May 22, 1966). "Computer a Help to 'Friendly Doc'; Automated Letter Writer Can Dispense a Cheery Word". The New York Times. p. 348.

Automated cordiality will be one of the services offered to physicians and dentists who take space in a new medical center.... The typist will insert the homey touch in the appropriate place as the Friden automated, programmed "Flexowriter" rattles off the form letters requesting payment... or informing that the X-ray's of the patient (kidney) (arm) (stomach) (chest) came out negative.

- Rostky, Georgy (2000). "The word processor: cumbersome, but great". EETimes. Retrieved 2006-05-29.

- Kirschenbaum, Matthew (March 1, 2013). "The Book-Writing Machine: What was the first novel ever written on a word processor?". Slate. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

- Smith, William D. (December 16, 1974). "Electric Typewriter Sales Are Bolstered by Efficiency". The New York Times. p. 57.

- Thomas, David (1983). Knights of the New Technology. Toronto: Key Porter Books. p. 94. ISBN 0-919493-16-5.

- CBC Television, Venture, "AES: A Canadian Cautionary Tale" http://archives.cbc.ca/economy_business/business/clips/14928/ . Broadcast date February 4, 1985, minute 3:50.

- Thomas, David "Knights of the New Technology". Key Porter Books, 1983, p. 97 & p. 98.

- “Will success spoil Steve Dorsey?”, Industrial Management magazine, Clifford/Elliot & Associates, May 1979, pp. 8 & 9.

- “Will success spoil Steve Dorsey?”, Industrial Management magazine, Clifford/Elliot & Associates, May 1979, p. 7.

- Thomas, David "Knights of the New Technology". Key Porter Books, 1983, p. 102 & p. 103.

- "1970–1979 C.E.: Media History Project". University of Minnesota. May 18, 2007. Retrieved 2008-03-29.

- Schuyten, Peter J. (1978): "Wang Labs: Healthy Survivor" The New York Times December 6, 1978 p. D1: "[Market research analyst] Amy Wohl... said... 'Since then, the company has installed more of these systems than any other vendor in the business."

- "NBI INC Securities Registration, Form SB-2, Filing Date Sep 8, 1998". secdatabase.com. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- Pea, Roy D. and D. Midian Kurland (1987). "Cognitive Technologies for Writing". Review of Research in Education. 14: 277–326. JSTOR 1167314.

- Bergin, Thomas J. (Oct–Dec 2006). "The Origins of Word Processing Software for Personal Computers: 1976–1985". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 28 (4): 32–47. doi:10.1109/MAHC.2006.76.

- Freiberger, Paul (1982-05-10). "Electric Pencil, first micro word processor". InfoWorld. p. 12. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- Freiberger, Paul; Swaine, Michael (2000). Fire in the Valley: The Making of the Personal Computer (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. pp. 186–187. ISBN 0-07-135892-7.

- Shrayer, Michael (November 1984). "Confessions of a naked programmer". Creative Computing. p. 130. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- Eisenberg, Daniel (1992). "Word Processing (History of)". Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science (PDF). 49. New York: Dekker. pp. 268–78. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 21, 2019.

- Brinkley, Joel (2000-09-21). "It's a Word World, Or Is It?". The New York Times.

External links

| Wikiversity has learning resources about Word processing challenges |

- FOSS word processors compared: OOo Writer, AbiWord, and KWord by Bruce Byfield

- History of Word Processing

- "Remembering the Office of the Future: Word Processing and Office Automation before the Personal Computer" - A comprehensive history of early word processing concepts, hardware, software, and use. By Thomas Haigh, IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 28:4 (October–December 2006):6-31.

- "A Brief History of Word Processing (Through 1986)" by Brian Kunde (December, 1986)

- "AES: A Canadian Cautionary Tale" by CBC Television (Broadcast date: February 4, 1985, link updated Nov. 2, 2012)