Woolsthorpe by Belvoir

Woolsthorpe by Belvoir, also known as Woolsthorpe is a village and civil parish in the South Kesteven district of Lincolnshire, England. The population of the civil parish at the 2011 census was 415.[1] It is situated approximately 5 miles (8 km) west from Grantham, and adjoins the county border with Leicestershire. The neighbouring village of Belvoir lies on the other side of the border. Grantham Canal is situated 1 mile (1.6 km) to the north-east at its closest point.

| Woolsthorpe by Belvoir | |

|---|---|

Bottom Lock, Woolsthorpe | |

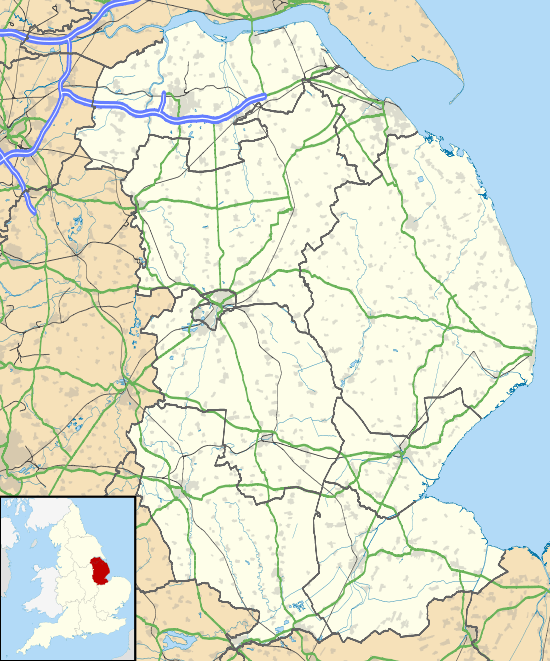

Woolsthorpe by Belvoir Location within Lincolnshire | |

| Population | 415 (2011) |

| OS grid reference | SK837340 |

| • London | 100 mi (160 km) SSE |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Grantham |

| Postcode district | NG32 |

| Police | Lincolnshire |

| Fire | Lincolnshire |

| Ambulance | East Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

History

Etymology

According to A Dictionary of British Place Names, the name Woolsthorpe means "an outlying farmstead or hamlet (Old Scandinavian 'thorp') of a man called Wulfstan (Old English person name)".[2]

Early history

In the 1086 Domesday account Woolsthorpe is referred to as "Ulestanestorp",[3] in the Kesteven Hundred of Winnibriggs and Threo. It comprised 29 households, 6 villagers, 3 smallholders and 8 freemen, with 4 ploughlands and 3 mills. In 1066 Leofric of Bottesford was Lord of the Manor, this transferred in 1086 to Robert of Tosny, who also became Tenant-in-chief.[4]

A possible deserted medieval village lies at the southern edge of the present village just to the east off Woolsthorpe Lane,[5] on the same site of a previous St James church destroyed in 1643 by Parliamentary forces.[6] Of the destruction Kelly's Directory wrote in 1885: "the original church of St. James, of which some fragments of the tower remain, was burned down by soldiers of the Parliamentary Army who bivouacked there during the siege of Belvoir Castle".[7][8]

Further evidence of medieval and earlier occupation are finds of a stone macehead at the centre of the village,[9] Roman coins and a Middle Bronze Age cinerary urn to the south-west,[10][11] and medieval ridge and furrow earthworks, and a trackway seen through cropmarks, to the north.[12][13] Approximately 1 mile (1.6 km) north from Woolsthorpe is the deserted medieval village of Stenwith, defined by moat, ditch, enclosure, hollow way and croft (homestead with land) earthworks.[14] Stenwith is recorded in the Domesday account as "Stanwald" or "Stanwalt".[15] in the Lincolnshire Hundred of Winnibriggs and Threo. It was part of the manor of Barrowby and comprised 21 households, 2 smallholders and 19 freemen, with 4 ploughlands, 15 acres (0.1 km2) of meadow and one mill. In 1066 Godwin of Barrowby was Lord of the Manor, this transferred in 1086 to Robert Malet, who also became Tenant-in-chief.[16]

19th. century

In 1885 Kelly's describes Woolsthorpe as situated on the River Devon, close to the borders of Leicestershire. It was in the wapentake of Winnibriggs and Threo, the petty sessional division of Spittlegate, the union and county court district of South Grantham, and in the Archdeaconry and Diocese of Lincoln. The nearest railway station was noted as 3.5 miles (5.6 km) away at Sedgebrook, on the Great Northern Railway line. Parts of the "plantations and pleasure grounds of Belvoir Castle... are in this parish"; Belvoir castle was supplied with water from the parish's Holywell spring. The parish area of 2,600 acres (11 km2) had a rateable value of £2,983. Crops grown were chiefly wheat, barley and oats. Parish population in 1881 was 598.[7]

In 1879 the Stanton Iron Company began quarrying for marl ironstone at Woolsthorpe, on land leased from the Duke of Rutland. The ore was taken by horse and cart to the Grantham Canal. The Great Northern Railway built a branch to Woolsthorpe in 1883. At first ironstone to be transported by trains run by the Stanton company via the Grantham to Nottingham mainline. Later this line was operated by the Great Northern. A 3 ft (914 mm) gauge tramway carried the ore from the quarries to the Great Northern branch. The northern end of the tramway was a cable-worked incline. Horses were used to pull the wagons on the upper section of the tramway until the first steam locomotive arrived in November 1883. The first quarry was at Brewer's Grave to the north of the Denton Road and west of Longmoor Lane. The quarries were extended to the east, north and south of this and then into the parish of Harston in Leicestershire to the south. The quarries at Woolsthorpe were worked out by 1923 but quarrying carried on at Harston and later Knipton and Denton for many years.[17][18] The Woolsthorpe tramway was abandoned around 1918 by which time the Woolsthorpe branch of the Great Northern branch had been extended to a point in Denton Parish just north of the Denton to Harston Road to serve the quarries. Another tramway linked the southernmost Woolsthope quarries to the new branch terminus. The mainline branch was still used to carry ironstone until the closure of the Denton quarries in 1974.[17]

One steam locomotive used on the tramway survived. Nancy was built in 1908 for the Stanton Ironworks Company. She is now preserved in working order at the Cavan and Leitrim Railway in Ireland.[19]

Kellys in 1885 also recorded the Duke of Rutland KG as lord of the manor and chief landowner. Within the village were a boot-and-shoe maker, two shopkeepers-cum-carriers, a shoemakers with post office, a butcher-cum-grocer, two carpenters, two tailors, two shopkeepers, a blacksmith, a baker-cum-beer retailer, two farmers, a butcher-cum-farmer, and a homoeopathist. There were two public houses, the Rutland Arms and the Chequers, and a ladies boarding and day school. Living in the village was a gamekeeper and a farm bailiff, both in the employ of the Duke of Rutland, and a surgeon medical officer who was public vaccinator for the Denton district and Grantham Union. Five carriers from the village delivered to Grantham's Blue Man, Blue Ram, and Blue Bull public houses.[7]

20th.century

The village was designated a conservation area by South Kesteven Council in 1997.[20]

Landmarks

Woolsthorpe Grade II listed Anglican church is dedicated to St James.[21] It was built of ironstone in 1845-47 by G. G. Place, replacing an earlier 1793 church on the same site.[8][22] Kellys wrote of the church and its history:

The church of St. James is a building of stone, in the Decorated style, erected in 1845-6 from designs by Mr. G. G. Place, of Nottingham, and consisting of chancel, nave, aisles and a tower, as yet unfinished: it has a very elaborately carved Perpendicular font, and the east window and some others are stained... [following the destruction of the earlier church in 1643] services were afterwards held in the Chapel of St. Mary, a small building in the middle of the village, which was taken down in 1793, and a church erected on the same site: the present edifice will seat 400 persons. The register of baptisms date from 1663; marriages, 1662; burials, 1661. The living is a rectory, tithe rent-charge £80, net yearly value £230, including 38 acres of glebe with residence, in the gift of the Duke of Rutland K.G. and held since 1879 by the Rev. Edward Alfred Gillett M.A. of Exeter College, Oxford.[7]

On Village Street is a Grade II listed former County Primary School and schoolmaster's house.[23] It was built in the style of St James' Church.[22] In 1885 Kellys described the school as an "elementary School (mixed), built in 1871, at a cost of £1,200, for 120 children, with an average attendance of 112; & supported by voluntary subscriptions, school pence & government grant."[7]

Further listed buildings include the red-brick mid-18th-century Woolsthorpe House on Belvoir Lane, and the red-brick Rectory on Rectory Lane, dating from the late 18th century.[24][25] Pevsner mentions the wharf on the Grantham Canal which was used to unload stone, and "charming lock cottages".[22]

Of the ironstone workings little can be seen today except for the remains of the cable worked incline and the remains of the branch railway. In places it can be seen that the level of the fields and lanes has been lowered.[26]

References

- "Civil Parish population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- Mills, Anthony David (2003); A Dictionary of British Place Names, pp.509, 524, Oxford University Press, revised edition (2011). ISBN 019960908X

- "Documents Online: Woolsthorpe, Lincolnshire", Great Domesday Book, Folios: 353r, 377r; The National Archives. Retrieved 19 July 2012

- "Woolsthorpe-by-Belvoir", Domesdaymap.co.uk. Retrieved 19 July 2012

- Historic England. "Woolsthorpe (871903)". PastScape. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- Historic England. "St James Church (323846)". PastScape. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- Kelly's Directory of Lincolnshire with the port of Hull 1885, p. 716

- Cox, J. Charles (1916) Lincolnshire p. 343, 344; Methuen & Co. Ltd.

- Historic England. "Monument No. 323852". PastScape. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- Historic England. "Monument No. 323837". PastScape. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- Historic England. "Monument No. 323840". PastScape. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- Historic England. "Monument No. 1068888". PastScape. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- Historic England. "Monument No. 1068650". PastScape. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- Historic England. "Stenwith (323744)". PastScape. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- "Documents Online: Stenwith, Lincolnshire", Great Domesday Book, Folios: 368r, 377r; The National Archives. Retrieved 19 July 2012

- "Stenwith", Domesdaymap.co.uk. Retrieved 19 July 2012

- Tonks 1992, pp. 146–150.

- Wright, Neil R. (1982); Lincolnshire Towns and Industry 1700-1914; pp. 170, 171. History of Lincolnshire Committee for the Society for Lincolnshire History and Archaeology. ISBN 0902668102

- "One in, One out at Cavan & Leitrim as Nancy steams". Steam Railway. 26 April 2019.

- "Woolsthorpe-by-Belvoir"; Lincshar.org. Retrieved 19 July 2012

- Historic England. "Church of St James (1168645)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Harris, John; The Buildings of England: Lincolnshire p. 715; Penguin, (1964); revised by Nicholas Antram (1989), Yale University Press. ISBN 0300096208

- Historic England. "County Primary School and Schoolmaster's House (1360357)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- Historic England. "Woolsthorpe House (1306937)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- Historic England. "Rectory, Rectory Lane (1062298)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- Tonks 1992, p. 150.

Bibliography

- Tonks, Eric (1992). The Ironstone Quarries of the Midlands Part 9: Leicestershire. Cheltenham: Runpast Publishing. ISBN 1-870-754-085.

External links

- "Woolsthorpe (or Woolsthorpe by Belvoir)"; Genuki. Retrieved 19 July 2012