William Zorach

William Zorach (February 28, 1889 – November 15, 1966)[1] was a Lithuanian-born American sculptor, painter, printmaker, and writer. He won the Logan Medal of the arts. He is notable for being at the forefront of American Artists embracing cubism, as well as for his sculpture.

William Zorach | |

|---|---|

William Zorach circa 1917, photographed by Man Ray | |

| Born | Zorach Gorfinkel February 28, 1887 Jurbarkas, Lithuania, Russian Empire |

| Died | November 15, 1966 (aged 79) Bath, Maine, U.S. |

| Known for | Sculpture, painting, printmaking |

| Elected | American Academy of Arts and Letters (1953) |

He is the husband of Marguerite Thompson Zorach and father of Dahlov Ipcar, both artists in their own right.

Early life

Zorach Gorfinkel was born in 1889 into a Lithuanian Jewish family, the son of a barge owner[2], in Jurbarkas (Russian: Eurburg) in Lithuania (then a part of the Russian Empire) As the eighth of ten children, Zorach (then his given name) emigrated with his family to the United States in 1894. They settled in Cleveland, Ohio under the name "Finkelstein". In school, his first name was changed to "William" by a teacher. Zorach stayed in Ohio for almost 15 years pursuing his artistic endeavors. He apprenticed with a lithographer as a teenager and went on to study painting with Henry G. Keller in night school at the Cleveland School of Art from 1905 to 1907.[3] In 1908, Zorach moved to New York in enroll in the National Academy of Design.[4] In 1910, Zorach moved to Paris with Cleveland artist and lithographer, Elmer Brubeck, to continue his artistic training at the La Palette art school.[5]

Career

While in Paris, Zorach met Marguerite Thompson (1887–1968), a fellow art student of American nationality, whom he would marry on December 24, 1912, in New York City.[6] The couple adopted his original given name, Zorach, as a common surname. Zorach and his wife returned to America where they continued to experiment with different media.[5] In 1913, works by both Zorach and Marguerite, were included in the now famous Armory Show, introducing his work to the general public as well as art critics and collectors.[7] Both William and Marguerite were heavily influenced by cubism and fauvism. They are credited as being among the premiere artists to introduce European modernist styles to American modernism.[5] During the next seven years, Zorach established himself as a painter, frequently displaying his paintings in gallery shows as venues such as the Society of Independent Artists and the Whitney Studio Club.[8] While Marguerite began to experiment with textiles and created large, fine art tapestries and hooked rugs, William began to experiment with sculpture, which would become his primary medium.[5]

In 1915, William and Marguerite started their family with the birth of their son, Tessim.[1] Their daughter, Dahlov Ipcar, was born in 1917, and would later also work as an artist.[5] While the Zorach family spent their winters in New York, their summers were divided between New Hampshire and Massachusetts.[5] Notably, they spent a few summers in Plainfield, New Hampshire at the Cornish Art Colony, renting Echo Farm which was owned by their friend and fellow artist Henry Fitch Taylor. It was here that their daughter was born, all the while producing various prints depicting country life.[9] He was also a member of the Provincetown Printers art colony in Massachusetts.[10]

In 1923 the Zorach family purchased a farm on Georgetown Island, Maine where they resided, worked, and entertained guests.[5] Zorach was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1953,[11] and received a D.F.A. from Bates College in 1964. He taught at the Art Students League of New York, between 1929 and 1960. He continued to actively work as an artist until his death in Bath, Maine, on November 15, 1966.

Works

Zorach's works can be found in numerous private, corporate, and public collections across the country including such acclaimed locales as the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, Radio City Music Hall, the Currier Museum of Art, Joslyn Art Museum, as well as numerous college and university collections.[12] His work was also part of the sculpture event in the art competition at the 1932 Summer Olympics.[13]

Puma, in the National Gallery of Art

Puma, in the National Gallery of Art- Puma

- Moses

- Dimitri Mitriopoulos, International Music Competition Medal

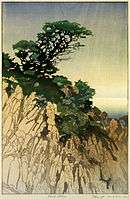

Brooklyn Museum - Tree - Yosemite - William Zorach - overall

Brooklyn Museum - Tree - Yosemite - William Zorach - overall_and_Figures_in_Landscape_(verso)_-_Marguerite_Thompson_Zorach_-_framed.jpg) Brooklyn Museum - Skiff in Waves (recto) and Figures in Landscape (verso) - Marguerite Thompson Zorach - framed

Brooklyn Museum - Skiff in Waves (recto) and Figures in Landscape (verso) - Marguerite Thompson Zorach - framed New Horizons. Bronze sculpture, 1951, approximately 42 inches high.

New Horizons. Bronze sculpture, 1951, approximately 42 inches high. William Zorach, Floating Figure. 1922. Bronze. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Georgia.

William Zorach, Floating Figure. 1922. Bronze. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Georgia.

References

- "William Zorach". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved October 22, 2009.

- Milwaukee Art Center (1976). From Foreign Shores: Three Centuries of Art by Foreign Born American Masters. Milwaukee: Milwaukee Art Center.

- Hoopes, Donelson F. (1968). William Zorach. Brooklyn: Brooklyn Museum.

- Wingert, Paul S. (1938). The Sculpture of William Zorach. New York: Pitman Publishing Corporation. p. 10.

- Hanson, Jayna. "A Finding Aid to the Zorach Family Papers, 1900–1987, in the Archives of American Art". Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- "Marguerite Thompson Zorach (1887-1968)". Hollis Taggart Galleries. 2008. Archived from the original on October 13, 2012.

- Wingert, Paul S. (1938). The Sculpture of William Zorach. New York: Pitman Publishing Corporation. p. 12.

- Wingert, Paul S. (1938). The Sculpture of William Zorach. New York: Pitman Publishing Corporation.

- "Impressionist & Modern Art - Sale 14PT03 - Lot 88 - Doyle New York". www.doylenewyork.com. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- "Provincetown Printers/A Woodcut Tradition". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- "Deceased Members". American Academy of Arts and Letters. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- "Inventory". wiscassetbaygallery.com.

- "William Zorach". Olympedia. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to William Zorach. |

- Official website run by some of Zorach's grandchildren, dedicated to the work of their grandparents.

- "To Be Modern: The Origins of Marguerite and William Zorach's Creative Partnership, 1911–1922", Jessica Nicoll, Portland Museum of Art

- "Works of William Zorach" at the Wiscasset Bay Gallery

- swope.org

- ilovefiguresculpture.com

- Biographies on art.com: short, long