Whitesboro, New York

Whitesboro is a village in Oneida County, New York, United States. The population was 3,772 at the 2010 census. The village was named after Hugh White, an early settler who had been adopted into the Oneida tribe and built the first permanent settlement there in 1784-85.[5]

Whitesboro, New York | |

|---|---|

Commercial buildings on Main Street in Whitesboro | |

.png) Seal | |

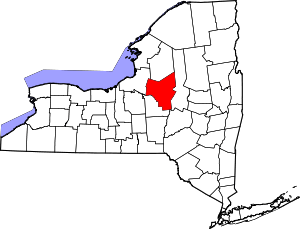

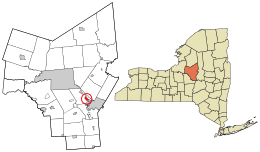

Location in Oneida County and the state of New York. | |

| Coordinates: 43°7′N 75°18′W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New York |

| County | Oneida |

| Founded by | Hugh White (New York) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1.05 sq mi (2.72 km2) |

| • Land | 1.05 sq mi (2.72 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 423 ft (129 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 3,772 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 3,612 |

| • Density | 3,440.00/sq mi (1,328.68/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 13492 |

| Area code(s) | 315 |

| FIPS code | 36-81710[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0971160[4] |

The Village of Whitesboro is inside the Town of Whitestown.

History

The village began to be settled in 1784, and was incorporated in 1813. An 1851 list gave the name Che-ga-quat-ka for Whitesboro in a language of the Iroquois people.[6]

The abolitionist Oneida Institute was located in Whitesboro from 1827 to 1843.

The older part of the village was bordered by the Erie Canal and the village's Main Street. When the canal was filled in the first half of the 20th century, Oriskany Boulevard was built over the filled-in canal. The streets that connect the two roads form the oldest part of the village.

The Whitestown Town Hall was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973.[7]

City seal controversy

.jpeg)

The Whitesboro seal, originating in the early 1900s, displays founder Hugh White wrestling an Oneida Native American.[8] The seal has been controversial because it has been interpreted as a settler choking the Native American; city officials contend it depicts a friendly wrestling match that White won, gaining the respect of the Oneida.[9] The current version of the seal was created in 1970, after a lawsuit by a Native American group: the version used before the suit showed the settler's hands on the Native American's neck instead of his shoulders.[10]

The seal attracted more controversy in 2016 when village residents voted 157 to 55 to keep the seal as-is rather than explore alternative images.[9] On January 21, 2016, Patrick O'Connor, the mayor of Whitesboro, called Jessica Williams, a correspondent for The Daily Show, and told her that the town would change the seal.[11]

An updated seal was adopted in the summer of 2017.[12] The new seal was created by Marina Richmond, a student at the PrattMWP College of Art and Design in Utica.[13] While the new seal depicts the same scene as the previous seal it has been changed so that it no longer depicts the Native American as being strangled.[14] Additionally, inaccuracies like the design of the headdress worn by the Oneida chief have been corrected as well as the attire of Hugh White. The skin tone of the Oneida chief has also been whitened.[15]

Geography

Whitesboro is located at 43°7′N 75°18′W (43.124, -75.296).[16]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the village has a total area of 1.1 square miles (2.8 km2), all land.[17] The Sauquoit Creek runs through the village.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1870 | 964 | — | |

| 1880 | 1,370 | 42.1% | |

| 1890 | 1,663 | 21.4% | |

| 1900 | 1,958 | 17.7% | |

| 1910 | 2,375 | 21.3% | |

| 1920 | 3,038 | 27.9% | |

| 1930 | 3,375 | 11.1% | |

| 1940 | 3,532 | 4.7% | |

| 1950 | 3,902 | 10.5% | |

| 1960 | 4,784 | 22.6% | |

| 1970 | 4,805 | 0.4% | |

| 1980 | 4,460 | −7.2% | |

| 1990 | 4,195 | −5.9% | |

| 2000 | 3,943 | −6.0% | |

| 2010 | 3,772 | −4.3% | |

| Est. 2019 | 3,612 | [2] | −4.2% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[18] | |||

As of the census[3] of 2000, there were 3,943 people, 1,778 households, and 992 families residing in the village. The population density was 3,675.4 people per square mile (1,422.8/km²). There were 1,921 housing units at an average density of 1,790.6 per square mile (693.2/km²). The racial makeup of the village was 97.69% White, 0.53% African American, 0.03% Native American, 0.33% Asian, 0.53% from other races, and 0.89% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.47% of the population.

There were 1,778 households out of which 27.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 36.9% were married couples living together, 15.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 44.2% were non-families. 39.0% of all households were made up of individuals and 18.7% had someone living alone who were 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.21 and the average family size was 2.98.

In the village, the population was spread out with 23.3% under the age of 18, 7.8% from 18 to 24, 31.7% from 25 to 44, 20.3% from 45 to 64, and 17.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females, there were 86.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 81.2 males.

The median income for a household in the village was $31,947, and the median income for a family was $42,741. Males had a median income of $29,408 versus $25,865 for females. The per capita income for the village was $17,386.

Notable people

- Robert Esche, former professional ice hockey goaltender, currently President of the Utica Comets

- George Washington Gale, founder of the Oneida Institute of Science and Industry, later the Oneida Institute

- Beriah Green, president of the Oneida Institute

- William A. Moseley, former US Congressman

- Mark Mowers, former professional ice hockey winger

- Mark Lemke, former Major League baseball player with the Atlanta Braves

- William Whipple Warren, 19th-century historian of the Ojibwe and Minnesota Territory legislator, attended school at the Oneida Institute

- Philo White, former Wisconsin state senator, U.S. diplomat

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- Transactions of the Oneida Historical Society at Utica, 1881–1884, p.73 et seq. (1885)

- Jones, Pomroy (1851). Annals and recollections of Oneida County. Rome, New York: Published by the author. p. 872.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- Katz, Brigit. "New York Village Changes Controversial Seal Showing a White Settler Wrestling a Native American". Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- Santora, Marc (January 12, 2016). "Residents in Whitesboro, N.Y., vote to keep a much-criticized village emblem". The New York Times.

- Potts, Courtney (January 4, 2009). "Whitesboro seal 'takes a little explaining'". Observer-Dispatch.

- "Wrestling with History in Whitesboro, NY". The Daily Show. 21 January 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- "Whitesboro officially replaces controversial seal". September 25, 2017.

- Koren, Cindiana. “Solving Racism – Whitesboro – UPDATE.” http://meetinghouse.co/solving-racism-whitesboro-ny-update/ Accessed 30 Sept. 2017.

- Maya Salam (27 September 2017). "New York Village's Seal, Widely Criticized as Racist, Has Been Changed". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 September 2017 – via www.nytimes.com.

- http://www.uticaod.com/news/20170926/after-past-uproar-whitesboro-has-new-village-seal

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- Bureau, US Census. "Search Results". www.census.gov. Retrieved 2017-09-29.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

External links

- Village of Whitesboro, NY