Waterside Mill, Ashton-under-Lyne

Waterside Mill, Ashton-under-Lyne was a combined cotton spinning weaving mill in Whitelands, Ashton-under-Lyne, Greater Manchester, United Kingdom. It was built as two independent factories. The weaving sheds date from 1857; the four-storey spinning mill dates from 1863. The spinning was taken over by the Lancashire Cotton Corporation in the 1930s. Production finished in the 1950s. Waterside Mill was converted to electricity around 1911.[2]

| |

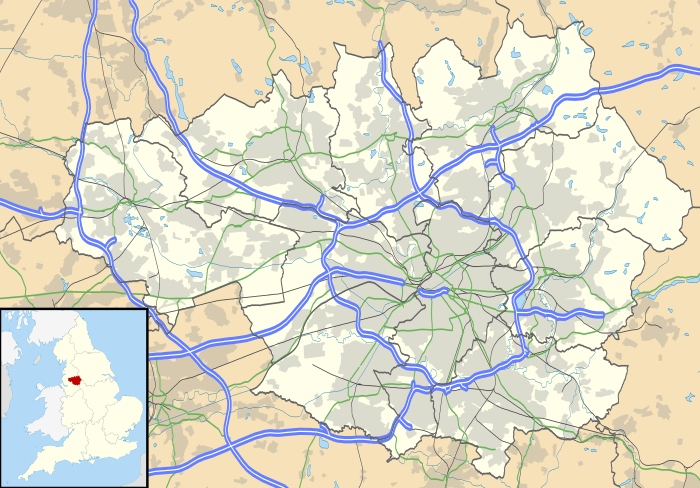

Location within Greater Manchester | |

| Cotton | |

|---|---|

| Spinning (mule mill) and Weaving shed | |

| Location | Ashton |

| Serving canal | Huddersfield Narrow Canal |

| Serving railway | Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway |

| Owner | Thomas Mellor & Sons |

| Further ownership |

|

| Coordinates | 53.4833°N 2.0861°W |

| Construction | |

| Built | 1863 (main mill) |

| Floor count | 4 |

| Power | |

| Date | 1880 |

| Engine maker | George Saxon & Co |

| Engine type | horizontal compound |

| Equipment | |

| No. of looms | 990(1911) |

| Mule Frames | 34,256 spindles (1884–1911) |

| References | |

| [1][2] | |

Location

Ashton-under-Lyne is a market town in the Metropolitan Borough of Tameside, Greater Manchester, England.[3] Historically a part of Lancashire, it lies on the north bank of the River Tame, on undulating land at the foothills of the Pennines. To the south of the river is the town of Dukinfield, which Historically a part of Cheshire. Ashton (as it is often shortened to) is 3.8 miles (6.1 km) south-southeast of Oldham, 6.1 miles (9.8 km) north-northeast of Stockport, and 6.2 miles (10.0 km) east of the city of Manchester. The Portland Basin in Ashton was the terminus of the Ashton Canal, and the start of both the Huddersfield Narrow Canal and the Peak Forest Canal. Ashton was served by the Ashton, Stalybridge and Liverpool Junction Railway from 1844, and then with further lines created by the Oldham, Ashton and Guide Bridge Railway in 1861.

History

Until the introduction of the cotton trade in 1769, Ashton was considered "bare, wet, and almost worthless".[4] The factory system, and textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution triggered a process of unplanned urbanisation in the area, and by the mid-19th century Ashton had emerged as an important mill town at a convergence of newly constructed canals and railways. Ashton-under-Lyne's transport network allowed for an economic boom in cotton spinning, weaving, and coal mining, which led to the granting of honorific borough status in 1847.

The engine of growth in the second half of the nineteenth century was the joint stock company, whereby capital could be raised for the construction of new mills. The first joint stock boom was in the early 1860s was cut short by the Lancashire Cotton Famine. During the second boom between 1873 and 1875 about a dozen companies were formed, half were 'Turn-over' companies which bought existing mills from private owners. New mills were built at Whitelands and Guide Bridge. The third wave was from 1880 to 1884; only five companies were formed in Ashton of which two built mills, one being a weaving shed. The fourth and last boom of 1889 to 1892 saw the building of seven substantial mills by the 'Ashton Syndicate'.[5]

Waterside Mill began as two independent manufactories. The earliest factory was a weaving shed erected by Thomas Mellor and Sons in 1857, at Sharp's Shrubberies in Whitelands, they already had a combined mill on Gas Street which could not be expanded. The Whitelands mill was a four-storey building built by George Harry Mellor, and leased to the Waterside Mill Company, who were registered with a capital of £20,000. It was equipped with 34,256 mule spindles. By 1896 both buildings were being operated by Thomas Mellor and Sons, and before the First World War the mills were physically joined. Waterside became a combined mill, weaving fancies from coarser cotton counts of American cottons.[2]

The industry peaked in 1912 when it produced 8 billion yards of cloth. The Great War of 1914–18 halted the supply of raw cotton, and the British government encouraged its colonies to build mills to spin and weave cotton. The war over, Lancashire never regained its markets. The independent mills were struggling. Waterside Mill was split into two units again. The Bank of England set up the Lancashire Cotton Corporation in 1929 to attempt to rationalise and save the industry.[6] The spinning side of Waterside Mill, Ashton-under-Lyne was one of 104 mills bought by the LCC, and one of the 53 mills that survived through to the early 1950s. The weaving sheds passed to Tattersall's Limited and closed in the 1930s.[2]

Architecture

Power

A pair of George Saxon & Co horizontal compound engines delivering 640 iHP. This was removed by 1911 when the mill was electrically driven. [2][7]

Equipment

- 34,256 mule spindles (1884–1911)

- 56,220 ring spindles (1911–1930s), 65,488 (1938)

- 774 looms (1903) 970 looms (1911)

Usage

Owners

- Thomas Mellor and Sons (1857) – Weaving Sheds

- George Mellor (1963) – Spinning

- Lancashire Cotton Corporation (1930s–1964) – Spinning

- Tattersalls – Weaving

See also

- Textile manufacturing

- Cotton Mill

References

- LCC 1951

- Haynes 1987, p. 42

- Greater Manchester Gazetteer, Greater Manchester County Record Office, Places names - A, archived from the original on 18 July 2011, retrieved 20 September 2008

- Wilson (1870–1872).

- Haynes 1987, p. 4

- Dunkerley

- Roberts 1921

Notes

Bibliography

- Dunkerley, Philip (2009). "Dunkerley-Tuson Family Website, The Regent Cotton Mill, Failsworth". Retrieved 9 January 2009.

- LCC (1951). The mills and organisation of the Lancashire Cotton Corporation Limited. Blackfriars House, Manchester: Lancashire Cotton Corporation Limited.

- Haynes, Ian (1987). Cotton in Ashton. Libraries and Arts Committee, Tameside Metropolitan Borough. ISBN 0-904506-14-2.

- Roberts, A S (1921), "Arthur Robert's Engine List", Arthur Roberts Black Book., One guy from Barlick-Book Transcription, retrieved 11 January 2009

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Textile mills in Greater Manchester. |