Ring spinning

Ring spinning is a method of spinning fibres, such as cotton, flax or wool, to make a yarn. The ring frame developed from the throstle frame, which in its turn was a descendant of Arkwright's water frame. Ring spinning is a continuous process, unlike mule spinning which uses an intermittent action. In ring spinning, the roving is first attenuated by using drawing rollers, then spun and wound around a rotating spindle which in its turn is contained within an independently rotating ring flyer. Traditionally ring frames could only be used for the coarser counts, but they could be attended by semi-skilled labour.[1]

History

Early machines

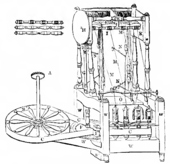

- The Saxony wheel was a double band treadle spinning wheel. The spindle rotated faster than the traveller in a ratio of 8:6, drawing was done by the spinners fingers.

- The water frame was developed and patented by Arkwright in the 1770s. The roving was attenuated (stretched) by draughting rollers and twisted by winding it onto a spindle. It was heavy large-scale machine that needed to be driven by power, which in the late 18th century meant by a water wheel.[2] Cotton mills were designed for the purpose by Arkwright, Jedediah Strutt and others along the River Derwent in Derbyshire. Water frames could only spin weft.[2]

- The throstle frame was a descendant of the water frame. It used the same principles, was better engineered and driven by steam. In 1828 the Danforth throstle frame was invented in the United States. The heavy flyer caused the spindle to vibrate, and the yarn snarled every time the frame was stopped. Not a success.[3]

- The Ring frame is credited to John Thorp in Rhode Island in 1828/9 and developed by Mr. Jencks of Pawtucket, Rhode Island, who Richard Marsden names as the inventor.[3]

Developments in the United States

Machine shops experimented with ring frames and components in the 1830s. The success of the ring frame, however, was dependent on the market it served and it was not until industry leaders like Whitin Machine Works in the 1840s and the Lowell Machine Shop in the 1850s began to manufacture ring frames that the technology started to take hold.[4]

At the time of the American Civil War, the American industry boasted 1,091 mills with 5,200,000 spindles processing 800,000 bales of cotton. The largest mill, Naumkeag Steam Cotton Co. in Salem, Mass.had 65,584 spindles. The average mill housed only 5,000 to 12,000 spindles, with mule spindles out-numbering ring spindles two-to-one.[5]

After the war, mill building started in the south, it was seen as a way of providing employment. Almost exclusively these mills used ring technology to produce coarse counts, and the New England mills moved into fine counts.

Jacob Sawyer vastly improved spindle for the ring frame in 1871, taking the speed from 5000rpm to 7500rpm and reducing the power needed, formerly 100 spindles would need 1 hp but now 125 could be driven. This also led to production of fine yarns.[6] During the next ten years, the Draper Corporation protected its patent through the courts. One infringee was Jenks, who was marketing a spindle known after its designer, Rabbeth. When they lost the case, Mssrs. Fales and Jenks, revealed a new patent free spindle also designed by Rabbeth, and also named the Rabbeth spindle.

The Rabbeth spindle was self-lubricating and capable of running without vibration at over 7500 rpm. The Draper Co. bought the patent and expanded the Sawyer Spindle Co. to manufacture it. They licensed it to Fales & Jenks Machine Co., the Hopedale Machine Co., and later, other machine builders. From 1883 to 1890 this was the standard spindle, and William Draper spent much of his time in court defending this patent.[6]

Adoption in Europe

The new method was compared with the self-acting spinning mule which was developed by Richard Roberts using the more advanced engineering techniques in Manchester. The ring frame was reliable for coarser counts while Lancashire spun fine counts as well. The ring frame was heavier, requiring structural alteration in the mills and needed more power. These were not problems in the antebellum cotton industry in New England. It fulfilled New England's difficulty in finding skilled spinners: skilled spinners were plentiful in Lancashire. In the main the requirements on the two continents were different, and the ring frame was not the method of choice for Europe at that moment.

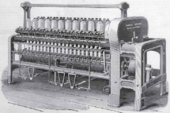

Mr Samuel Brooks of Brooks & Doxey Manchester was convinced of the viability of the method. After a fact-finding tour to the States by his agent Blakey, he started to work on improving the frame. It was still too primitive to compete with the highly developed mule frames, let alone supersede them. He first started on improving the doubling frame, constructing the necessary tooling needed to improve the precision of manufacture. This was profitable and machines offering 180,000 spindle were purchased by a sewing thread manufacturer.[7]

Brooks and other manufacturers now worked on improving the spinning frame. The principal cause for concern was the design of the Booth-Sawyer spindle. The bobbin did not fit tightly on the spindle and vibrated wildly at higher speeds. Howard & Bullough of Accrington used the Rabbath spindle, which solved these problems. Another problem was ballooning, where the thread built up in an uneven manner. This was addressed by Furniss and Young of Mellor Bottom Mill, Mellor by attaching an open ring to the traverse or ring rail. This device controlled the thread, and consequently a lighter traveller could be made which could operate at higher speeds. Another problem was the accumulation of fluff on the traveller breaking the thread - this was eliminated by a device called a traveller cleaner.[8]

A major time constraint was doffing, or changing the spindles. Three hundred or more spindles had to be removed, and replaced. The machine had to be stopped while the doffers, who were often very young boys, did this task. The ring frame was idle until it was completed.[9] Harold Partington (1906 - 1994) of Chadderton, England, patented a 'Means for Doffing Ring Frames' in September 1953 (US Patent 2,653,440). The machine removed full bobbins from the ring frame spindles, and placed empty bobbins onto the spindles in their place; eight spindles at a time. It was traversable along the front of the ring frame step by step through successive operations, and thereby reduced the period of stoppage of the ring frame as well as reducing the labour required for removing all the filled bobbins on a frame and replacing them with empty bobbins. The Partington autodoffer was developed with assistance from Platt Brothers (Oldham) and worked perfectly in ideal conditions: flat horizontal floor and ring frame parallel to the floor and standing vertically. Sadly, these conditions were unobtainable in most Lancashire cotton mills at the time and so the autodoffer did not go into production. The Partington autodoffer was unique and the only one to work properly as an add-on to a ring frame. A more modern mechanical doffer system fitted as an integral part of the ring frame, reduced the doffing time to 30–35 seconds.

Rings and mules

The ring frame was extensively used in the United States, where coarser counts were manufactured. Many of frame manufacturers were US affiliates of the Lancashire firms, such as Howard & Bullough and Tweedales and Smalley. They were constantly trying to improve the speed and quality of their product. The US market was relatively small, the total number of spindles in the entire United States was barely more than the number of spindles in one Lancashire town, Oldham. When production in Lancashire peaked in 1926 Oldham had 17.669 million spindles and the UK had 58.206 million.[10]

Technologically mules were more versatile. The mules were more easily changed to spin the larger variety of qualities of cotton then found in Lancashire. While Lancashire concentrated on "Fines" for export, it also spun a wider range, including the very coarse wastes. The existence of the Liverpool cotton exchange meant that mill owners had access to a wider selection of staples.

The wage cost per spindle is higher for ring spinning. In the states, where cotton staple was cheap, the additional labour costs of running mules could be absorbed, but Lancashire had to pay shipment costs. The critical factor was the availability of labour, when skilled labour was scarce then the ring became advantageous.[11] This had always been so in New England, and when it became so in Lancashire, ring frames started to be adopted.

The first known mill in Lancashire dedicated to ring spinning was built in Milnrow for the New Ladyhouse Cotton Spinning Company (registered 26 April 1877). A cluster of smaller mills developed which between 1884 and 1914 out performed the ring mills of Oldham.[12] After 1926, the Lancashire industry went into sharp decline, the Indian export market was lost, Japan was self-sufficient. Textile firms united to reduce capacity rather than to add to it. It wasn't until the late 1940s that some replacement spindles started to be ordered and ring frames became dominant. Debate still continues in academic papers on whether the Lancashire entrepreneurs made the right purchases decisions in the 1890s.[11] The engine house and steam engine of the Ellenroad Ring Mill are preserved.

New technologies

- The search for faster and more reliable ring spinning techniques continues. In 2005, a PhD paper was written at Auburn University, Alabama on using magnetic levitation to reduce friction, a techniques known as Magnetic ring spinning.[13]

- Open end spinning was developed in Czechoslovakia in the years preceding 1967. It was far faster than ring spinning, and did away with many preparatory processes. Put simply, the thread was ejected spinning from a nozzle, and on exiting hooked onto other loose fibres in the chamber behind. It was first introduced into the United Kingdom at the Maple Mill, Oldham.

How it works

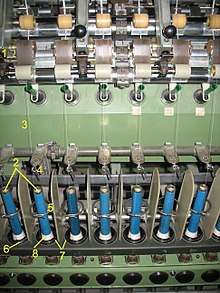

1 Drafting rollers

2 Spindle

3 Attenuated roving

4 Thread guides

5 Anti-ballooning ring

6 Traveller

7 Rings

8 Thread on bobbin

A ring frame was constructed from cast iron, and later pressed steel. On each side of the frame are the spindles, above them are draughting (drafting) rollers and on top is a creel loaded with bobbins of roving. The roving (unspun thread) passes downwards from the bobbins to the draughting rollers. Here the back roller steadied the incoming thread, while the front rollers rotated faster, pulling the roving out and making the fibres more parallel. The rollers are individually adjustable, originally by mean of levers and weights. The attenuated roving now passes through a thread guide that is adjusted to be centred above the spindle. Thread guides are on a thread rail which allows them to be hinged out of the way for doffing or piecing a broken thread. The attenuated roving passes down to the spindle assembly, where it is threaded though a small D ring called the traveller. The traveller moves along the ring. It is this that gives the ring frame its name. From here the thread is attached to the existing thread on the spindle.[14]

The traveller, and the spindle share the same axis but rotate at different speeds. The spindle is driven and the traveller drags behind thus distributing the rotation between winding up on the spindle and twist into the yarn. The bobbin is fixed on the spindle. In a ring frames, the different speed was achieved by drag caused by air resistance and friction (lubrication of the contact surface between the traveller and the ring was a necessity). Spindles could rotate at speeds up to 25,000 rpm, this spins the yarn. The up and down ring rail motion guides the thread onto the bobbin into the shape required: i.e. a cop. The lifting must be adjusted for different yarn counts.

Doffing is a separate process. An attendant (or robot in an automated system) winds down the ring rails to the bottom. The machine stops. The thread guides are hinged up. The completed bobbin coils (yarn packages) are removed from the spindles. The new bobbin tube is placed on the spindle trapping the thread between it and the cup in the wharf of the spindle, the thread guides are lowered and the machine restarted. Now all the processes are done automatically. The yarn is taken to a cone winder. Currently, machines are manufactured by Rieter (Switzerland), ToyoTa (Japan), Zinser, Suessen, (Germany) and Marzoli (Italy). The Rieter compact K45 system has 1632 spindles, while ToyoTa has a machine with 1824 spindles. All require controlled atmospheric conditions.

See also

- Carding

- Cotton mill

- Cotton-spinning machinery

- Dref Friction Spinning

- Magnetic ring spinning

- Open end spinning

- Spinning

- Spinning wheel

- Textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution

- Textile manufacturing

- Timeline of clothing and textiles technology

References

- Marsden 1884, p. 297

- Williams & Farnie 1992, p. 8

- Marsden 1884, p. 298

- "Investigating Disruptive Technology The Emergence Of Ring Spinning In The American Textile Industry". Harvard Business School, Baker Library. Retrieved 2009-04-30.

- Gilkerson, Yancy S. "Textile Industry Meets Demand Of Booming U.S. Population 1887–1900". Textile World. Retrieved 2009-04-30.

- "Hopedale inventors". Archived from the original on 2009-08-07. Retrieved 2009-04-30.

- Marsden 1884, p. 300

- Marsden 1884, p. 308

- Marsden 1884, p. 307

- Williams & Farnie 1992

- Leunig, Timothy (November 2002). "Can profitable arbitrage opportunities in the raw cotton market explain Britain's continued preference for mule spinning?" (PDF). London: London School of Economics. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Toms (1998). "Growth profit and Technological Choice. The case for the Lancashire Cotton Industry". Journal of Industrial History.

- "Ring-spinning-system-for-making-yarn-having-a-magnetically-elevated-ring". Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- Marsden 1884, p. 302

Bibliography

- Nasmith, Joseph (1895). Recent Cotton Mill Construction and Engineering (Elibron Classics ed.). London: John Heywood. ISBN 1-4021-4558-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marsden, Richard (1884). Cotton Spinning: its development, principles and practice. George Bell and Sons 1903. Retrieved 2009-04-26.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marsden, ed. (1910). Cotton Yearbook 1910. Manchester: Marsden and Co. Retrieved 2009-04-26.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Williams, Mike; Farnie (1992). Cotton Mills of Greater Manchester. Carnegie Publishing. ISBN 0-948789-89-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ring spinning. |

- A complete spinning website - Describes the blow room, carding, Ring spinning, OE, fibre testing, textile calculations etc.

- Ring Spinning - Articles on Ring Spinning machines, processes and technologies.

- Auto-doffing videos