Conservation issues of Pompeii and Herculaneum

Pompeii and Herculaneum were once thriving towns, 2,000 years ago, in the Bay of Naples. Though both cities have rich histories influenced by Greeks, Oscans, Etruscans, Samnites and finally the Romans, they are most renowned for their destruction: both were buried in the AD 79 eruption of Mount Vesuvius.[1] For over 1,500 years, these cities were left in remarkable states of preservation underneath volcanic ash, mud and rubble. The eruption completely obliterated the towns but ironically was the cause of their longevity and survival over the centuries.

However, for both cities, excavation has brought with it deterioration, as both natural forces and human activity (whether accidental or deliberate) have played their part in the slow disintegration of the sites.[2] Problems range from paintings being exposed to light and buildings being worn away by weathering, erosion and water damage to inappropriate excavation and reconstruction methods to outright theft and vandalism. As stated by Henri de Saint-Blanquat:

The city's second existence began with its gradual rediscovery in the 18th century. But just when Pompeii was being rediscovered, it began to die its second death. Not only because the early excavations, carried out over two hundred years ago and again in the 19th century, often turned out to be more of a massacre — what fun to carry off statues and fling around inscribed bronze plaques! — but also because all the remains preserved by the catastrophic explosion, were now exposed to the extremes of the weather, to vegetation and to man... Pompeii suffers from pollution, the worst forms of damage are of human origin.

— Henri de Saint-Blanquat, Science et Avenir

The ancient city was included in the 1996 World Monuments Watch by the World Monuments Fund, and again in 1998 and in 2000. In 1996, the organization claimed that Pompeii "desperately need[ed] repair" and called for the drafting of a general plan of restoration and interpretation.[3]

Problems of conservation

While the excavation of the cities has led to a wealth of information on the two towns and on Roman life in general, it has also allowed the sites to come under the attack of the elements. Some of this is unpreventable; however, much of it can be slowed or completely stopped through human intervention. Unfortunately, funding is in such a state that not everything can be saved. An estimated US$335 million is needed to carry out all the works necessary in Pompeii alone.

Weathering and erosion

Pompeii and Herculaneum have been excavated for centuries (excavations began in 1738 in Herculaneum, and later in 1748), and all exposed structures have been affected by general deterioration over time. In particular, since the eruption disrupted many of the buildings, excavation has left them unstable and vulnerable to collapse, such as the town wall of Pompeii. In many places, walls have partially collapsed, and much of the site is closed to visitors because of the danger it poses to them.

Many artifacts themselves are also damaged by natural processes. In Herculaneum, the carbonised remains of objects, once exposed to the air, deteriorated within days. Only when a substance (lampblack) was applied were they able to survive in the open. Also in Herculaneum, the bones of hundreds of victims found at the beach have been left in the open air due to a lack of funding, and are steadily disintegrating.

Light exposure

The frescoes, sculptures and paintings prevalent in both towns were highly preserved, retaining a large amount of detail, colour and vibrancy. Unfortunately, on excavation, they began to fade due to exposure to natural light, as well as beginning to crumble and pull away from the walls. However, these issues can be resolved through simple conservation techniques: earlier organic methods of preservation proved effective, and a more modern method using aluminium and plastic has had even better results. In addition, detailed reproductions have been made of many of the artworks, such as the Alexander Mosaic in the House of the Faun.

Not all actions taken to preserve structures and artefacts have been effective, however, and some have caused more damage. For example, perspex cases have been constructed to protect frescoes and graffiti, however this creates a humidity trap and causes damage to the plaster.

Plants and animals

The region of Campania in which both sites lie is very temperate and fertile, so many plants thrive even inside the archaeological site. Henri de Saint-Blanquat identifies thirty-one plants in Pompeii, which, after growing in patches of bare earth, grow outward and attack the surrounding buildings, as well as dislodging tiles and mosaics. In particular, ivy grows along the walls, making parts crumble, and the roots undermine the foundations of the buildings. In regions traversed by tourists, their feet trample the plants; in closed-off areas, particularly those closest to unexcavated parts of the cities, this severely damages the buildings.

Feral dogs were particularly an issue in Pompeii. The dogs which occupied buildings around the Forum in the 1980s have been removed. Hundreds lived on the site, inadvertently damaging footpaths, roads and walls, as well as proving aggressive towards some tourists.

In Herculaneum, pigeons are a particular problem; the acidic nature of their feces wears away the roofs and walls of many structures. Italian law prohibits them from being shot.

Human activity

Early excavations

Particularly in Herculaneum, the earliest excavations revolved around collecting valuable artifacts and antiquities rather than systematic excavation. By merely digging for objects with aesthetic and commercial value, they were taken from being in situ to private collections, and thus much of the information on them was lost. Additionally, other objects not considered worthy by pursuers of Antiquarianism were destroyed, or damaged in the process of retrieving other items.

These valuable objects, once discovered, were also disorganised and lost all historical meaning: a collection of bronze letters originally fixed on a wall in Herculaneum, once removed by the Bourbon kings, were taken out of order without recording the original placement or meaning. Visitors were invited to re-arrange them to form their own messages. A similar usage was made of bones: they would often be arranged together as composites of bones of several individuals, even combining those of children with adults and giving some literally two left feet. These would then be displayed for dramatic effect. Some of these remain today, but there is little hope of re-forming the original skeletons or using them to discover information on the inhabitants of Pompeii or Herculaneum.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bazzani Watercolors of Pompeii. |

Gallery of Luigi Bazzani's Watercolors of Pompeii when first excavated

(See more on Wikimedia Commons)

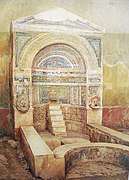

Summer Triclinium of House V, 2, 15, 1914

Summer Triclinium of House V, 2, 15, 1914 Pompeii Bath

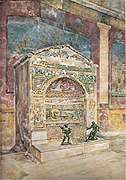

Pompeii Bath Lararium of the House of Dioscuri, 1902

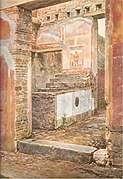

Lararium of the House of Dioscuri, 1902 House of the Great Fountain

House of the Great Fountain Atrium of the House of the Centenary, 1901

Atrium of the House of the Centenary, 1901.jpg) Peristyle with fountain in the House of Marcus Lucretius

Peristyle with fountain in the House of Marcus Lucretius Peristyle with fountain in the House of Marcus Lucretius (Detail)

Peristyle with fountain in the House of Marcus Lucretius (Detail).jpg) Pompeii Interior

Pompeii Interior.jpg) Pompeii theater

Pompeii theater.jpg) Lararium of the House IX,1,7, Pompeii,1903

Lararium of the House IX,1,7, Pompeii,1903 Nymphaeum at the House of the Bull, 1901

Nymphaeum at the House of the Bull, 1901 Atrium of the House of the Mariner

Atrium of the House of the Mariner_before_1927.jpg) House of the Vetti

House of the Vetti House of the Small Fountain

House of the Small Fountain House with impluvium and marble table

House with impluvium and marble table Insula in Region IX, V, 18

Insula in Region IX, V, 18 Temple of Isis

Temple of Isis Thermopolion (fast food stall) in the alley of the rooster

Thermopolion (fast food stall) in the alley of the rooster Fountain with head of Mercury on Mercury Street

Fountain with head of Mercury on Mercury Street House of the Hanging Balcony

House of the Hanging Balcony Portal of a patrician house on Augustus Street

Portal of a patrician house on Augustus Street Tomb in the necropolis

Tomb in the necropolis Tomb with covered niche and planter with garland

Tomb with covered niche and planter with garland Lararium in the House of L Caecilius Jucundus

Lararium in the House of L Caecilius Jucundus Pompeii Atrium

Pompeii Atrium Arches of Nero in the Forum

Arches of Nero in the Forum Pompeian red interior

Pompeian red interior_of_the_House_of_Sallust_(VI_2%2C_4)_in_Pompei_watercolor_by_Luigi_Bazzani.jpg) The Genaeceum (Women's Quarters) of the House of Sallust (VI 2, 4)

The Genaeceum (Women's Quarters) of the House of Sallust (VI 2, 4) Thermopolium in the Alley of the Pharmacist

Thermopolium in the Alley of the Pharmacist Atrium of the House of the Ancient Hunt

Atrium of the House of the Ancient Hunt_in_Pompeii_watercolor_by_Luigi_Bazzani.jpg) Atrium of the House of the Ancient Hunt (Detail)

Atrium of the House of the Ancient Hunt (Detail) Atrium in Pompeii

Atrium in Pompeii Atrium of the House of the Vetti VI.15.1

Atrium of the House of the Vetti VI.15.1 Entry to a Roman domus

Entry to a Roman domus Atrium of the House of the Prince of Naples

Atrium of the House of the Prince of Naples_in_Pompeii_watercolor_by_Luigi_Bazzani.jpg) Fountain of the House of C. Virnius Modestus (IX 7, 16)

Fountain of the House of C. Virnius Modestus (IX 7, 16) Atrium of the House of Cornelius Rufus

Atrium of the House of Cornelius Rufus Colonnade of the House of Cornelius Rufus

Colonnade of the House of Cornelius Rufus House of the Silver Wedding

House of the Silver Wedding Lararium of a family altar, seen in situ after excavation, House of Aulus Vettius, Pompeii, c36-39 CE, 1895

Lararium of a family altar, seen in situ after excavation, House of Aulus Vettius, Pompeii, c36-39 CE, 1895 Lararium of the House of Paccius Alexander (IX 1, 7)

Lararium of the House of Paccius Alexander (IX 1, 7) Large theater in Pompeii, 1910,

Large theater in Pompeii, 1910, Pompeii forum

Pompeii forum The Temple of Fortuna Augusta

The Temple of Fortuna Augusta

Reconstruction efforts

Amedeo Maiuri, director of Pompeii and Herculaneum from 1924 to 1961, was intent on re-creating the "atmosphere" of the two towns as they were just prior to the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius. Though some directors before him had taken limited steps towards this, Maiuri was motivated to reconstruct much of the infrastructure of the two towns. This meant rebuilding walls and roofs that had been knocked down by the eruption to reproduce the facade of the towns. This was particularly important in Pompeii, where the roofs and anything more than two metres above ground level were destroyed by the eruptions.

Unfortunately, the materials used in this reconstruction were mostly concrete and steel. The mix of the cement was particularly bad in many places, and the alkaline in the masonry reacted with the ancient stones, causing crumbling and erosion to walls of structures such as the House of the Coloured Capitals, as well as peeling off any existing paint.

After the 1980s, these materials used in reconstruction were replaced by more modern ones which would not react badly with the original work, and the old reconstructions are being gradually replaced; however, the damage has already been done in most places, and the replacement endeavours will take many more years to complete.

Tourism

Tourism has been a mixed blessing for the site. As there are 2.5 million visitors to both cities every year, their presence allows for education on the conservation issues on the site. Additionally, a law was passed in Italy in 1997, which allowed for all money raised from these tourists to be directly channeled to helping with the conservation of the site.

However, the massive number of tourists also causes many problems. The general movement of them causes the gradual wearing down of the roads and pavements, particularly in the more frequented areas like the Pompeiian Forum complex. Tourists also might take chips of rock or stone from the site, as well as accidentally brushing against the walls and frescoes, further increasing their rate of deterioration. The open nature of both sites to tourists is also a leading cause in vandalism and theft.

Vandalism and war

Vandalism, particularly graffiti, is a problematic issue for Pompeii and Herculaneum. Tourists and others often break off parts of the city's structures to take home as mementos or souvenirs. Graffiti appears inscribed in the walls (often alongside their ancient counterparts) as well as on paintings and frescoes, particularly the less damaged or unsullied works of art. The site was also bombed by Allied air forces during the Second World War, and many of its buildings needed to be reconstructed in the postwar period.[4]

Theft

While both areas are guarded, many artifacts still find their way to the illicit antiquities market. Often these acts of theft also cause accidental damage to surrounding objects, and the thieved antiquities are no longer in situ and lose their context and cultural associations.

In 2003, two frescoes were hacked off a wall in the House of the Chaste Lovers in Pompeii. This act of theft also damaged several other frescoes in the house, and, though a camera system exists in Pompeii, it had been out of operation for several months when the event took place. These frescoes were recovered some months later, but many others have disappeared from the site, never to be returned.

House of the Gladiators collapse

The 2,000-year-old “House of the Gladiators” in the ruins of ancient Pompeii collapsed on 6 November 2010. Known officially by its Latin name “Schola Armatorum ” the structure was not open to visitors but was visible from the outside as tourists walked along one of the ancient city's main streets. There was no immediate word on what caused the building to collapse, although reports suggested water infiltration following heavy rains might be responsible. There has been fierce controversy regarding the collapse.[5] [6]

Conservation projects

There are many conservation projects, endeavours and enterprises associated with both cities in an attempt to prevent further deterioration. These focus on removing the forces that attack the sites, as well as restoring the damaged artefacts and preventing further destruction.

Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli e Pompeii

The Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli e Pompeii is the major administrative body of both sites and others in the Naples and Vesuvuian area. It has overall responsibility for caring for both ancient cities, managing the sites, conserving them, working towards the removal of plants, providing security to prevent further theft, administering tourist entry into the site and reconstructing various buildings. It also directs many other subsidiary projects, and controls all funding and access to the two cities. Projects such as the restoration of frescoes and sculptures in Pompeii are run by the institute. Additionally, modern technology is used to help in conservation; in 2006, a laser survey was created of the Forum complex, allowing a three-dimensional, digital reconstruction.

Moratorium

In 1999, Pietro Giovanni Guzzo declared a moratorium on all further excavations of both sites. As then superintendent, he decided that all funds should be diverted into preserving the remains of both cities, rather than excavating more when massive amounts of work is still needed on the areas already unearthed. This has caused controversy amongst historians and archaeologists, and has become the centre of the debate on whether to focus on conservation or excavation. Classicists argue that only by continuing excavations can more ancient texts be found to reveal more about ancient Roman life. In particular, they pin their hopes on the unexcavated chamber of the Villa of the Papyri, where over 1,800 carbonised papyrus rolls have been discovered containing works of Epicurean philosophy by Philodemus. However, those in favour of conservation argue that the texts are much safer underground than exposed and we still have much to draw from what has already been excavated.

Minor excavations, such as that of the House of the Surgeon currently being undertaken by the Anglo-American Project at Pompeii at a cost of 10 million euro a year, are still allowed. However, no new sites are open to be excavated.

Herculaneum Conservation Project

As a joint project led by the Packard Humanities Institute and the Soprintendenza Speciale per I Beni Archaeologici di Napoli e Pompeii with the British School at Rome, the project has worked since 2001 to halt the serious decay conditions which were found at the site. Initially the work focused on an emergency campaign which then transformed into works to ensure the long-term maintenance of the site. A major emphasis has been placed on ensuring that infrastructures work effectively so that when the project is completed, the Soprintendenza will be in a good position to manage the continuous care of the site. In addition scientific research is under way so that suitable methodologies can be identified to conserve Herculaneum's wall paintings, plasters, mosaics, wooden features, structures, etc.[7]

References

- Roberts, Paul (2013). Life and Death in Pompeii and Herculaneum. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199987436.

- Amery, Colin; Curran, Brian (2002). The Lost World of Pompeii. Getty Publications. p. 35. ISBN 9780892366873.

- World Monuments Fund, List of 100 Most Endangered Sites - 1996 Archived 2013-03-20 at the Wayback Machine, New York, NY: 1996, p. 31.]

- "The Last Days of Pompeii (Getty Villa Exhibitions)". www.getty.edu.

- "World News - Breaking International Headlines & Exclusives | Toronto Sun".

- "Pompeii Gladiator Training Centre Collapses". Archived from the original on 2010-11-13.

- Hammer, Joshua. "The Fall and Rise and Fall of Pompeii". Retrieved 2015-07-01.

Other sources

- Allison, Penelope (2004). Pompeian Households: An Analysis of the Material Culture. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology. ISBN 0-917956-96-6. Archived from the original on 2007-02-11. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- Hurley, Toni; et al. (2005). Antiquity 3. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-551687-7. Archived from the original on 2006-09-17. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- Zarmati, Louise (2005). Heinemann ancient and medieval history: Pompeii and Herculaneum. Heinemann. ISBN 1-74081-195-X. Archived from the original on 2006-09-04. Retrieved 2019-11-14.