Erotic art in Pompeii and Herculaneum

Erotic art in Pompeii and Herculaneum has been both exhibited as art and censored as pornography. The Roman cities around the bay of Naples were destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, thereby preserving their buildings and artefacts until extensive archaeological excavations began in the 18th century. These digs revealed the cities to be rich in erotic artefacts such as statues, frescoes, and household items decorated with sexual themes. The ubiquity of such imagery and items indicates that the treatment of sexuality in ancient Rome was more relaxed than current Western culture. (However, much of what might strike modern viewers as erotic imagery (e.g. oversized phalluses) could arguably be fertility imagery. Depictions of the phallus, for example, could be used in gardens to encourage the production of fertile plants.) This clash of cultures led to many erotic artefacts from Pompeii being locked away from the public for nearly 200 years.

In 1819, when King Francis I of Naples visited the Pompeii exhibition at the Naples National Archaeological Museum with his wife and daughter, he was embarrassed by the erotic artwork and ordered it to be locked away in a "secret cabinet", accessible only to "people of mature age and respected morals". Re-opened, closed, re-opened again and then closed again for nearly 100 years, the Secret Museum, Naples was briefly made accessible at the end of the 1960s (the time of the sexual revolution) and was finally re-opened for viewing in 2000. Minors are still only allowed entry to the once-secret cabinet in the presence of a guardian, or with written permission.

Phalluses

- Phallus relief from Pompeii, c. 1–50 AD

- Bronze 'flying phallus' amulet (1st C BC)

The phallus (the erect penis), whether on Pan, Priapus or a similar deity, or on its own, was a common image. It was not seen as threatening or even necessarily erotic, but as a ward against the evil eye.[1][2] The phallus was sculpted in bronze as tintinnabula (wind chimes). Phallus-animals were common household items. Note the child on one of the wind chimes.

Priapus

Wall mural of Mercury/Priapus

Wall mural of Mercury/Priapus Wall Painting of Priapus, House of the Vetti

Wall Painting of Priapus, House of the Vetti

A wall fresco which depicted Priapus, the god of sex and fertility, with his oversized erection, was covered with plaster (and, as Karl Schefold explains (p. 134), even the older reproduction below was locked away "out of prudishness" and only opened on request) and only rediscovered in 1998 due to rainfall.[3] The Romans believed that he was a talisman protecting the riches of the house.</ref>

The second image, from Schefold, Karl: Vergessenes Pompeji: Unveröffentlichte Bilder römischer Wanddekorationen in geschichtlicher Folge. München 1962., with its much more brilliant colors, has been used to retouch the younger, higher resolution image here.

Brothels

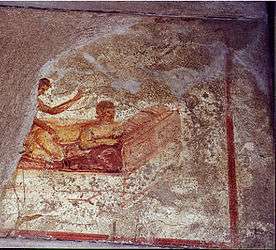

Fresco from the largest Pompeii brothel

Fresco from the largest Pompeii brothel An erotic wall painting on the walls of a small room at the side of the kitchen from The House of the Vettii, Pompeii.(cf. "Erotic Art in Pompeii" by Michael Grant, p. 52)

An erotic wall painting on the walls of a small room at the side of the kitchen from The House of the Vettii, Pompeii.(cf. "Erotic Art in Pompeii" by Michael Grant, p. 52)

It is unclear whether the images on the walls were advertisements for the services offered or merely intended to heighten the pleasure of the visitors. As previously mentioned, some of the paintings and frescoes became immediately famous because they represented erotic, sometimes explicit, sexual scenes.

One of the most curious buildings recovered was in fact a Lupanar (brothel), which had many erotic paintings and graffiti inside. The erotic paintings seem to present an idealised vision of sex at odds with the reality of the function of the lupanar. The Lupanare had 10 rooms (cubicula, 5 per floor), a balcony, and a latrina. It was not the only brothel. The town seems to have been oriented to a warm consideration of sensual matters: on a wall of the Basilica (sort of a civil tribunal, thus frequented by many Roman tourists and travelers), an immortal inscription tells the foreigner: If anyone is looking for some tender love in this town, keep in mind that here all the girls are very friendly (loose translation). Other inscriptions reveal some pricing information for various services: Athenais 2 As, Sabina 2 As (CIL IV, 4150), The house slave Logas, 8 As (CIL IV, 5203) or Maritimus licks your vulva for 4 As. He is ready to serve virgins as well. (CIL IV, 8940). The amounts vary from one to two As up to several Sesterces. In the lower price range the service was not more expensive than a loaf of bread.

Prostitution was relatively inexpensive for the Roman male but it is important to note that even a low priced prostitute earned more than three times the wages of an unskilled urban labourer. However, it was unlikely a freed woman would enter the profession in hopes for wealth because most women declined in their economic status and standard of living due to demands on their appearance as well as their health.

Prostitution was overwhelmingly an urban creation. Within the brothel it is said prostitutes worked in a small room usually with an entrance marked by a patchwork curtain. Sometimes the woman's name and price would be placed above her door. Sex was generally the cheapest in Pompeii, compared to other parts of the Empire. All services were paid for with cash.

Suburban baths

These frescoes are in the Suburban Baths of Pompeii, near the Marine Gate.[4]

These pictures were found in a changing room at one side of the newly excavated Suburban Baths in the early 1990s. The function of the pictures is not yet clear: some authors say that they indicate that the services of prostitutes were available on the upper floor of the bathhouse and could perhaps be a sort of advertising, while others prefer the hypothesis that their only purpose was to decorate the walls with joyful scenes (as these were in Roman culture). The most widely accepted theory, that of the original archaeologist, Luciana Jacobelli, is that they served as reminders of where one had left one's clothes.

Collected below are high-quality images of erotic frescoes, mosaics, statues and other objects from Pompeii and Herculaneum.

Fresco from the suburban baths of a 2 male and 1 female threesome.

Fresco from the suburban baths of a 2 male and 1 female threesome. Fresco from the suburban baths depicting cunnilingus.[5]

Fresco from the suburban baths depicting cunnilingus.[5] Fresco from the suburban baths in cowgirl position

Fresco from the suburban baths in cowgirl position

Venus

Mural of Venus

Mural of Venus

The mural of Venus from Pompeii was never seen by Botticelli, the painter of The Birth of Venus, but may have been a Roman copy of the then famous painting by Apelles which Lucian mentioned.

Gallery

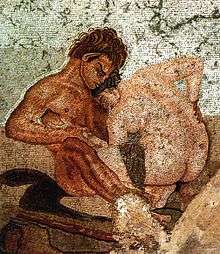

Tile mosaic, Satyr & Nymph, House of the Faun

Tile mosaic, Satyr & Nymph, House of the Faun Wall painting, House of the Epigrams, Reign of Nero

Wall painting, House of the Epigrams, Reign of Nero Marble bas-relief

Marble bas-relief Fresco from a Pompeii sleeping room

Fresco from a Pompeii sleeping room Erotic fresco

Erotic fresco

From the House of the Centenary; the woman is wearing a form of brassiere

From the House of the Centenary; the woman is wearing a form of brassiere

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ancient Roman erotic art. |

References

Notes

- Johns, C. "3: The Phallus and the Evil Eye". Sex or Symbol? Erotic Images of Greece and Rome. British Museum.

- Parker, A. (2017). "Protecting the Troops? Phallic Carvings in the north of Roman Britain". In Parker, A. (ed.). Ad Vallum: Papers on the Roman Army and Frontiers in Celebration of Dr Brian Dobson. BAR British Series 631. BAR Publishing. pp. 117–30.

- As reported by the epd press agency in March, 1998.

- "Repubblica.it/Galleria di immagini: Le terme del piacere: L'interno delle terme suburbane". repubblica.it.

- As this image shows cunnilingus, this image has elicited much interest, because it may contradict the popular male customer / female prostitute notion.

Bibliography and further reading

- Clarke, John (2003). Roman Sex: 100 B.C. to A.D. 250. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-1626548800.

- Grant, Michael; Mulas, Antonia (1997). Eros in Pompeii: The Erotic Art Collection of the Museum of Naples. New York: Stewart, Tabori and Chang. ISBN 978-1556706202.

- McGinn, Thomas A.J. (2004). The Economy of Prostitution in the Roman World. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0472113620.

- Varone, Antonio (2001). Eroticism in Pompeii. Getty Trust Publications. J. Paul Getty Museum. ISBN 978-0892366286.

External links

- Owen, Richard (27 October 2006). "Erotic frescoes put Pompeii brothel on the tourist map". The Times.