Well-made play

The well-made play (French: la pièce bien faite, pronounced [pjɛs bjɛ̃ fɛt]) is a dramatic genre from nineteenth-century theatre first codified by French dramatist Eugène Scribe. Dramatists Victorien Sardou, Alexandre Dumas, fils, and Emile Augier wrote within the genre, each putting a distinct spin on the style. The well-made play was a popular form of entertainment. By the mid-19th century, however, it had already entered into common use as a derogatory term.[1] Henrik Ibsen and the other realistic dramatists of the later 19th century (August Strindberg, Gerhart Hauptmann, Émile Zola, Anton Chekhov) built upon its technique of careful construction and preparation of effects in the genre problem play. "Through their example", Marvin Carlson explains, "the well-made play became and still remains the traditional model of play construction."[2]

In the English language, that tradition found its early 20th-century codification in Britain in the form of William Archer's Play-Making: A Manual of Craftmanship (1912),[3] and in the United States with George Pierce Baker's Dramatic Technique (1919).[4]

Form

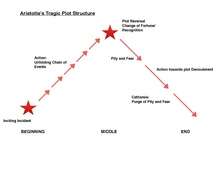

The form has a strong Neoclassical flavour, involving a tight plot and a climax that takes place close to the end of the play. The well-made play retains the shape of Aristotle's ideal Greek-tragedy model outlined in his Poetics.[5][6]

The well-made play can be broken down into a specific set of criteria.[7] First, the story depends upon a key piece of information kept from some characters, but known to others (and to the audience). Most of the story takes place before the action of the play begins, making the beginning of the play a late point of attack. Exposition during act one explains actions that precede the opening scene, and generates the audience's sympathy for the hero (or heroes) over their rival (or rivals). The plot moves forward in a chain of actions that use minor reversals of fortune to create suspense. The pace builds towards a climactic obligatory scene, in which the hero triumphs. This scene contains a climactic reversal of fortune, or peripeteia.[8] A dénouement follows, in which all remaining plot points are unraveled and resolved.[7]

A recurrent device that the well-made play employs is the use of letters or papers falling into unintended hands, in order to bring about plot twists and climaxes.[7] The letters bring about an unexpected and climactic reversal of fortune, in which it is often revealed that someone is not who they pretend to be. Mistaken or mysterious identity as a basis for plot complications is referred to as quid pro quo.[9][10]

Eugene Scribe contributed over 300 plays and opera libretti to the dramatic literature canon. Thirty-five of these works are considered well-made-plays.[11]

History

French Neoclassicism: a standard form

History of French Neoclassic form lays a critical foundation for Scribe, who draws upon devices determined by the French Academy to create his dramatic structure. French Neoclassicism conceives of Verisimilitude, or the appearance of a plausible truth, as the aesthetic goal of a play.[12] In 1638, the French Academy codified a system by which dramatists could achieve Verisimilitude in a verdict on the Le Cid debate.[12] The monarchy enforced the standards of French Neoclassicism with a system of censorship under which funding and practice permits were issued to a limited number of theater companies.[13] This system underwent small modifications, but remained essentially the same up until the French Revolution. Until then, restrictive laws inhibited the growth of new practices with the exception of those advocated by a few intrepid dramatists such as Voltaire, Diderot, and Beaumarchais. After the French Revolution, adherence to the form became an artistic choice instead of a political necessity.

Boulevard theatres: new forms

Although Scribe drew heavily upon Neoclassic devices, he used them in original ways that would not have been acceptable without new popular forms, such as those developed at the Boulevard theatres.[14] In order to work around the formal monopoly of the Comédie Française in the middle of the 18th century, theater troupes experimenting with new dramatic forms sprang up along the Boulevard du Temple. Their aim was to escape the censors, and please the public. Popular reception of the boulevard theatres' explorations helped to crack the edifice of Neoclassic form.[15] After the French Revolution, French theater opened to the influence of practices that had meanwhile developed in other places around Europe.[16]

Scribe's development of a form that could be used repeatedly to turn out new material suited the demands of a growing middle class theater audience.[17]

Criticism

On Scribe, Dumas fils, Augier, and Sardou

Scribe's influence on theater, according to Marvin J. Carlson, "cannot be overestimated".[18] Carlson observes that, unlike other influential theater thinkers, Scribe did not write prefaces or manifestos declaiming his ideas. Scribe influenced theater, instead, with craftsmanship. He honed a dramatic form into a reliable mould that could be applied not only to different content, but to different content from a variety of playwrights. Carlson identifies a single instance of Scribe's critical commentary from a speech Scribe gave to the Académie française in 1836. Scribe expressed his view of what draws the audiences to theater:

"not for instruction or improvement, but for diversion and distraction, and that which diverts them [audience] most is not truth, but fiction. To see again what you have before your eyes daily will not please you, but that which is not available to you in every day life - the extraordinary and the romantic."[18]

Although Scribe advocated for a theater of amusement over didacticism, other writers, beginning with Alexandre Dumas, fils, adopted Scribe's structure to create didactic plays. In a letter to a critic, Dumas fils states,"... if I can find some means to force people to discuss the problem, and the lawmaker to revise the law, I shall have done more than my duty as a writer, I shall have done my duty as a man.".[15] Dumas' thesis plays are plays written in the well-made style that take clear moral positions on social issues of the day. Emile Augier also used Scribe's formula to write plays addressing contemporary social issues, although he declares his moral position less strongly.[19]

By the late 19th century, the well-made play had fallen out of critical favor.[20] Shaw was among those who held the form in low regard, "Why the devil should a man write like Scribe when he can write like Shakespeare or Moliere, Aristophanes or Euripides? Who was Scribe that he should dictate to me or anyone else how a play should be written?"[9] In reference to the form's tendency to favor amusing plot twists over complexly drawn characters, Shaw referred to the genre as Sardoodledom after Victorien Sardou, who also wrote in the well-made style.[9]

Shaw and Ibsen

The opening to the preface to Three Plays by Brieux offers another example of Shavian disdain for the well-made plays. Shaw identifies the process of creating them as an industry, and their creators as “literary mechanics” instead of artists. To convey how vulgar he finds a widely used playwrighting formula, Shaw interprets the aphorism "Art for art's sake," as "Success for money's sake."[21]

In an essay published in PMLA in 1951, Pygmalion: Bernard Shaw’s Dramatic Theory and Practice, Milton Crane reasons that Shaw’s disparagement of the classic well-made formula, and his desire to pry Ibsen’s work away from association with the works of Scribe and Sardou, serve a specific agenda. Crane argues that Shaw aims to prevent his own use of the well-made formula from linking his plays with work considered out of fashion. Shaw’s theory of the problem play and discussion ideas align his plays with Ibsen’s, and distinguishes them from stale plays of the past. Crane observes that Shaw, by his own admission, learned dramatic structure from contemporary popular theatre which was then dominated by the well-made formula.[9] Crane goes on to argue how that formula is present in Pygmalion, Man and Superman, and The Doctor’s Dilemma.[22]

The problem play

Shaw discusses the notion of the problem play in an essay of the same title published in 1895.[23] He defines a problem play as one that puts a person or people in conflict with an institution, confronting a contemporary social question. He cites the "Woman question" as a contemporary example. Ibsen's engagement with the "Woman question" in A Doll's House and Ghosts qualifies those works as problem plays. Shaw distinguishes between the problem play and literature with conflicts reflecting a more universal view of the human condition. Works whose fundamental conflict does not pit human against institution, he argues, are more apt to remain relevant through generations. He cites Hamlet, Faust, and Les Misérables as examples of stories whose conflicts involve more eternal human questions. Shaw observes that the immediacy of the institutional question addressed in a problem play will render the play "flat as ditchwater" once society progresses and the issue is resolved.[23] Although Ibsen was hailed by feminists, he did not regard himself as an advocate for any particular group.[24]

The well-made play and modern drama

Ibsen's aim, according to Raymond Williams, was to express tragedies in the human condition. Ibsen qualifies a human tragedy as the state "[when a person] stands in a tight place; he cannot go forwards or backwards.”[25] Williams also cites the specific characteristic that distinguishes his and Ibsen's modern drama from the preceding well-made formula. The well-made formula, Shaw observes, can be divided into three sections: Exposition, Situation, Unraveling. The plays of Ibsen and Shaw, Shaw himself asserts, do not end with a classic unraveling. Their work can be divided as: Exposition, Situation, Discussion.[25]

Offshoots

Oscar Wilde's The Importance of Being Earnest exaggerates many of the conventions of the well-made play, such as the missing papers conceit (the hero, as an infant, was confused with the manuscript of a novel) and a final revelation (which, in this play, occurs about thirty seconds before the final curtain).[9]

Henrik Ibsen's A Doll's House follows most of the conceits of the well-made play, but transcends the genre when, after incriminating papers are recovered, Nora rejects the expected return to normality. Several of Ibsen's subsequent plays build on the general construction principles of the well-made play. The Wild Duck (1884) can be seen as a deliberate, meta-theatrical deconstruction of the Scribean formula. Ibsen sought a compromise between Naturalism and the well-made play which was fraught with difficulties since life does not fall easily into either form.[26]

Although George Bernard Shaw scorned the "well-made play", he accepted the form, and even thrived by it, for it concentrated his skills on the conversation among characters, his greatest asset as a dramatist.[27] Other classic twists on the well-made play can be seen in his use of the General's coat and the hidden photograph in Arms and the Man.

Also, J. B. Priestley's 1946 An Inspector Calls may in some ways be considered a "well-made play" in that its action happens before the play starts, and in the case of the older Birlings no moral change takes place. The similarity between Priestley's play and this rather conservative genre might strike some readers/audiences as surprising because Priestley was a socialist. However, his play, like Ibsen's A Doll's House transcends this genre by providing another plunge into chaos after the return to normality. He replaced the dramatic full stop with a question mark by revealing in the last scene that the 'inspector' who has exposed the complicity of a prosperous industrial family in the murder or suicide of a working-class girl, is not an inspector at all (perhaps a practical joker, an emanation of the world to come, or a manifestation of the world to come), and the curtain falls on the news that a real girl has died and a real inspector is on the way.[28]

The techniques of well-made plays also lend themselves to comedies of situation, often farce. In The Quintessence of Ibsenism, Bernard Shaw proposed that Ibsen converted this formula for use in "serious" plays by substituting discussion for the plausible dénouement or conclusion. Thus, plays become open-ended, as if there were life for the protagonists beyond the last act curtain.[29]

References

- Banham (1998), 964, 972–3, 1191–2.

- Carlson (1993, 216).

- Archer, William. Playmaking: a Manual of Craftsmanship. Public domain. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/10865

- J L Styan, Modern Drama in Theory and Practice I, quoted by Innes (2000, 7).

- The Internet Classics Archive by Daniel C. Stevenson, Web Atomics. Web. 11 Dec. 2014. http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/poetics.html

- Aristotle. "Poetics". Trans. Ingram Bywater. The Project Gutenberg EBook. Oxford: Clarendon P, 2 May 2009. Web. 26 Oct. 2014.

- Scribe, Eugene; ed. introd. Stanton, Stephen (1956). Camille and Other Plays. Hill and Wang. ISBN 0809007061.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- McBride, Augusto Boal ; translated by Charles A. & Maria-Odilia Leal (1985). Theatre of the oppressed (5th print. ed.). New York: Theatre Communications Group. ISBN 0930452496.

- Stanton, Stephen S. (December 1961). "Shaw's Debt to Scribe". MLA. 76 (5): 575–585.

- Holmgren, Beth. "Acting Out: Qui pro Quo in the Context of Interwar Warsaw." East European Politics & Societies (2012): 0888325412467053.

- Encyclopædia Britannica Editors. "well-made play". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- Ibbett, Katherine (2009). The Style of the State in French Theater, 1630-1660: Neoclassicism and Government. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

- Hildy, Franklin J.; Brockett, Oscar G. (2007). History of the theatre (Foundation ed.). Boston, Mass. [u.a.]: Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 0-205-47360-1.

- Brown, Frederick (1980). Theater and Revolution: the culture of the French stage. New York: Viking Press.

- Hildy, Oscar G. Brockett ; Franklin J. (2007). History of the theatre (Foundation ed.). Boston, Mass. [u.a.]: Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 0-205-47360-1.

- Carlson, Marvin A. (1966). The Theatre of the French Revolution. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP.

- Stanton, edited, with an introduction to the well-made play by Stephen S. (1999). Camille, and other plays. New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 0809007061.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Carlson, Marvin (1984). Theories of the Theatre: A Historical and Critical Survey from the Greeks to the Present. Ithaca and London: Cornell UP.

- Taylor, John Russell. The Rise and Fall of the Well-Made Play, Great Britain: Routledge, Cox and Wyman, Ltd.,1967. Print.

- Banham, Martin, ed. 1998. The Cambridge Guide to Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43437-8.

- Shaw, George Bernard. ‘’Three Plays by Brieux’’. New York: Brentano’s, 1911.

- Crane, Milton. "Pygmalion: Bernard Shaw's Dramatic Theory and Practice." PMLA 66.6 (1951): 879-85. JSTOR [JSTOR]. Web. 4 May 2015.

- Shaw, George Bernard (1958). "Problem Play". In West, E.J. (ed.). Shaw on Theatre. New York: Hill & Wang.

- Innes, Christopher. "Henrik Ibsen, Speech at the Festival of the Norwegian Women's Rights League, Christiana, 26 May 1898." A Sourcebook on Naturalist Theatre. London: Routledge, 2000. 74-75. Print.

- Williams, Raymond (1973). Drama from Ibsen to Brecht (2nd rev. ed.). Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 978-0140214925.

- Elsom, John. Post-War British Theatre. London: Routledge, 1976, p. 40.

- Elsom, John. Post-War British Theatre. London: Routledge, 1976, p. 43.

- Elsom, John. Post-War British Theatre. London: Routledge, 1976, p. 45.

- Shaw, Bernard. The Quintessence of Ibsenism. New York: Brentano's, 1913. Print.

Sources

- Banham, Martin, ed. 1998. The Cambridge Guide to Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43437-8.

- Cardwell, Douglas. "The Well-Made Play of Eugène Scribe," French Review (1983): 876-884. JSTOR. Web.10 Feb. 2015.

- Carlson, Marvin. 1993. Theories of the Theatre: A Historical and Critical Survey from the Greeks to the Present. Expanded ed. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8154-3.

- Elsom, John. 1976. Post-War British Theatre. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-7100-0168-1.

- "problem play". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, 2015. Web. 10 Feb. 2015

- "well-made play". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, 2015. Web. 10 Feb. 2015

- Innes, Christopher, ed. 2000. A Sourcebook on Naturalist Theatre. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-15229-1.

- Stanton, Stephen S. "Shaw's Debt to Scribe", PMLA 76.5 (1961): 575-585. JSTOR. Web. 10 Feb. 2015.

- Taylor, John Russell. The Rise and Fall of the Well-Made Play, Great Britain: Routledge, Cox and Wyman, Ltd.,1967. Print.

External links

- “The Well-Made Play of Eugène Scribe,” by Douglas Cardwell

- “Scribe’s ‘Bertrand Et Raton’: A Well-Made Play,” by Stephen S. Stanton

- Works by Eugène Scribe at Project Gutenberg

- Scribe's complete works: CEuvres completes d' Eugene Scribe, 76 vols. (Paris: E. Dentu, 1874-1885), Vols. I-IX.

- Playmaking: a Manual of Craftsmanship by William Archer

- Dramatic Technique by George Pierce Baker

- Scribe, Eugene. A Glass of Water. trans. Robert Cornthwaite. New Hampshire: Smith and Kraus. 1995. Web. April 19, 2015.