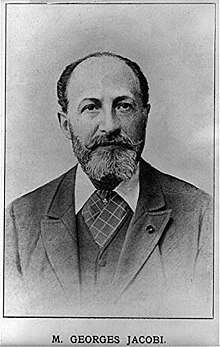

Georges Jacobi

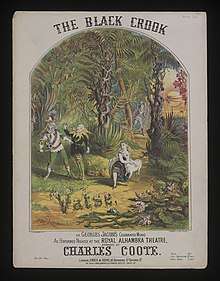

Georges Jacobi (3 February 1840 –13 September 1906) was a German violinist, composer and conductor who was musical director of the Alhambra Theatre in London from 1872 to 1898. His best-known work was probably The Black Crook (1872) written with Frederick Clay for the Parisian operetta-star Anna Judic and which ran for 310 performances. Although never achieving the standing of Hervé, or Offenbach or Sullivan, he composed over 100 pieces for ballet and the theatre which were popular at the time.[1]

Biography

Born in Berlin in Germany as Georg Jacobi and a German Jew,[2] his musical education began aged 6. Educated in Paris, he began his musical career as a violinist and in 1861 at the age of twenty-one he was awarded the first prize for violin playing at the Conservatoire de Paris where he also studied composition with Daniel Auber.[3] He entered the orchestra of the Opéra-Comique where he worked until 1869 as the first violinist. He also gave concerts with his own orchestra in the picture gallery of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. In 1869 he became musical director of the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens, where he mainly conducted operettas by Offenbach.[4]

With the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War Jacobi went to London where from 1872 to 1898 (except for 1883-84) he was musical director of the Alhambra Theatre.[4] Over the years, he composed more than 100 works for the ballet of the variety theatre. Jacobi produced a well received and entirely original score for the Alhambra's version of Carmen in 1879 owing to copyright issues over using the music of Bizet.[1]

After a fire in the Alhambra in 1882, the house was reopened in 1883 with a new concept. Between two ballet performances, a music hall programme was offered. The choreographer of the ballet was Carlo Coppi, who also opened a ballet school. The prima ballerina of the house was for a long time Emma Palladino.[5] In 1897 Arthur Sullivan composed the ballet Victoria and Merrie England, which was performed at the Alhambra and conducted by Jacobi.[6] In 1900 Jacobi became the conductor at the newly opened Hippodrome in London.[7]

In addition to ballets Jacobi composed several operettas and plays, as well as violin works, including two violin concertos.[3] In 1896 he became Professor of conducting at the Royal College of Music[1] where among his students were the composers Walter Slaughter and Gustav Holst. He was twice President of the Association of Conductors in England and was decorated both by the French Government and by the King of Spain.[3] In 1898 he took over the management of the summer theatre at The Crystal Palace;[1] his successor at the Alhambra was George W. Byng. He married Marie Charlotte Eleanore Pilatte (born 1846 in Paris; died 1910 in Paris)[8] and with her had two sons: the conductor Charles Auguste 'Maurice' Jacobi (1871-1939)[3] and Henri Louis Jacobi (1878-1935); and two daughters: Marguerite (born 1864) and Berthe (born 1869).[9]

On his death in 1906 Jacobi was buried in Highgate Cemetery, London.[10] In his will he left £4039 7s 6d to his widow.[11]

Works

Ballet music

- The Demon's Bride (1874)[12][13]

- The Fairies Home (1876)[1]

- Don Quixote (1876)[3][14]

- Yolande (1877)[2]

- Carmen (1879)[4]

- Titania[1]

- Ali Baba[1]

- The Swans (1884)[3]

- Don Juan (1885)[3]

- Melusine

- The Golden Wreath[1][2]

- Oriella

- La Tzigane

- Cupid (1886)[3]

- Nadia (1887)[15]

- Enchant-Pas Seulment (1887)[3]

- Dresdina (1887)[16]

- Antiope (1888)[3][16]

- The Water Queen (1889)[16]

- Tempta-Andantetion (1891)[3]

- Blue Beard (1895)

- Aladdin, Jr. (1895)[17]

- Lochinvar (1898)

- Beauty and the Beast (1898)[2]

- Cinderella (1898)[13]

Theatre Music

- Le feu aux poudres (1869)[13]

- Voila le plaisir, mesdames! (1869)[13]

- La Nuit du 15 Octobre (1869)[13]

- The Black Crook comic opera in collaboration with Frederic Clay (1872) and starring Anna Judic and Kate Santley[18]

- Mariée depuis midi, with Armand Liorat and William Busnach (1873)[13]

- Rothomago or The Magic Watch, operetta - joint composition with Edward Solomon, Procida Bucalossi and Gaston Serpette (1879)[19]

- Overture for Henry Irving's The Lyons Mail (1879)

- L'arbre de Noël (with Arnold Mortier) (1880)

- Le clairon (1883)[13]

- Music for The Dead Heart for Henry Irving (1889)[20]

- Music for Henry Irving's Robespierre by Victorien Sardou (1899)[1]

- Claudine et Trusquin (1903)[13]

- The Babes in the Wood (1905)[13]

Lyricist

- The revue A Dream of Whitaker's Almanack, with Walter Slaughter and Henry Pottinger Stephens (1899).[21]

- Mefistofele II (1880), Hervé (composer), with book by Georges Jacobi and C. Alfred.[22]

References

- Pfannkuch, Wilhelm, "Jacobi, George" in: New German Biography 10 (1974), p. 237 f. [Online version]; URL: https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd140771514.html#ndbcontent

- Georg Jacobi - Jewish Virtual Library

- The Alhambra in The Eighties' Ballet Music - BBC Radio Times 18 July 1929

- Michael Christoforidis and Elizabeth Kertesz, Carmen and the Staging of Spain: Recasting Bizet's Opera in the Belle Epoque, Oxford University Press (2019) - Google Books pg. 191

- Adrienne Simpson, Alice May: Gilbert & Sullivan's First Prima Donna, Routledge (2003) - Google Books pg. 116

- 1897 Theatre Programme from Victoria and Merrie England

- Silk Programme for the Hippodrome (1900) - Victoria and Albert Museum Collection

- Marie Charlotte Eleanore Jacobi in the Scotland, National Probate Index (Calendar of Confirmations and Inventories), 1876-1936 - Ancestry.com (subscription required)

- 1891 England Census for Georges Jacobi - Ancestry.com (subscription required)

- Burial of Georges Jacobi in Highgate Cemetery - Find a Grave

- Georges Jacobi in the England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1858-1966, 1973-1995 - Ancestry.com (subscription required)

- The Victorian Period: Excluding the Novel, The Macmillan Press Ltd (1983) - Google Books pg. 67

- Georges Jacobi: Opera and Oratorio Premieres - Stanford University Librsries database

- Robert Ignatius Letellier, Operetta: A Sourcebook, Volume II, Volume 2, Cambridge Scholars Publishing (2015) - Google Books pg. 900

- Orchestral Score for 'Nadia' by Georges Jacobi - Victoria and Albert Museum Collection

- John Franceschina, Incidental and Dance Music in the American Theatre from 1786 to 1923 Volume 1, BearManor Media (2018) - Google Books pg. 1826

- Franceschina, pg. 1894

- Franceschina, pg. 1892

- Edward Solomon - The Guide to Light Opera & Operetta

- Jeffrey Richards, Sir Henry Irving: A Victorian Actor and His World, Hambledon and London (2005) - Google Books pg. 253

- The Era, 10 June 1899, p. 8

- Mefistofele II: Grand Spectacular Comic Opera in Three Acts accessed 6.9.13

Bibliography

- Wilhelm Pfannkuch, Jacobi, Georg in: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 10, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1974, ISBN 3-428-00191-5, S. 237 f. (Digital).

- Jeffrey Richards, Imperialism and Music: Britain, 1876–1953, Manchester University Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0-7190-6143-1, S. 253 ff. (Google Books)