Velociraptorinae

Velociraptorinae is a subfamily of the theropod group Dromaeosauridae. The earliest velociraptorines are probably Nuthetes from the United Kingdom, and possibly Deinonychus from North America. However, several indeterminate velociraptorines have also been discovered, dating to the Kimmeridgian stage, in the Late Jurassic Period. These fossils were discovered in the Langenberg quarry, Oker near Goslar, Germany.[1]

| Velociraptorines | |

|---|---|

| |

| Holotype skull of Velociraptor mongoliensis, American Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Dromaeosauridae |

| Clade: | †Eudromaeosauria |

| Subfamily: | †Velociraptorinae Barsbold, 1983 |

| Type species | |

| †Velociraptor mongoliensis Osborn, 1924 | |

| Genera | |

| |

Description

While most velociraptorines were generally small animals, at least one species may have achieved gigantic sizes comparable to those found among the dromaeosaurines. So far, this unnamed giant velociraptorine is known only from isolated teeth found on the Isle of Wight, England. The teeth belong to an animal the size of dromaeosaurines of the genus Utahraptor, but they appear to belong to a velociraptorine, judging by the shape of the teeth and the anatomy of their serrations.[2]

In 2007 paleontologists studied front limb bones of Velociraptor and discovered small bumps on the surface, known as quill knobs. The same feature is present in some bird bones, and represents the attachment point for strong secondary wing feathers. This finding provided the first direct evidence that velociraptorines, like all other maniraptorans, had feathers.[3]

Distinguishing anatomical features

According to Currie (1995), Velociraptorinae can be distinguished based on the following characteristics: dromaeosaurids with maxillary and dentary teeth possessing denticles on the anterior carinae that are significantly smaller than the posterior denticles, and which have a second premaxillary tooth that is significantly larger than the third and fourth premaxillary teeth; dromaeosaurids with nasals that appear depressed, when observed in lateral view.[4]

According to Turner et al. (2012), Velociraptorinae can be distinguished based on the following unambiguous characteristics: the posterior opening of the basisphenoid recess is divided into two small, circular foramina by a thin bar of bone; the dorsal tympanic recess is present as a deep, posterolaterally directed concavity; pleurocoels are present in all of the dorsal vertebrae.[5]

Classification

When erected by Barsbold in 1983, Velociraptorinae was conceived as a group containing Velociraptor and supposed closely related species.[6] It was not until 1998 that this group was defined as a clade by Paul Sereno. Sereno defined the group as all dromaeosaurids more closely related to Velociraptor than to Dromaeosaurus.[7] While several studies have since recovered a group of dromaeosaurids closely related to Velociraptor, they vary widely regarding which species are actually velociraptorines and which are either more basal or closer to Dromaeosaurus.

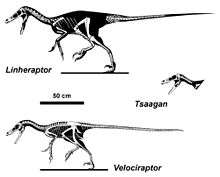

Novas and Pol (2005) found a distinct velociraptorine clade close to the traditional view, which included Velociraptor, Deinonychus, and material that was later named Tsaagan. A cladistic analysis conducted by Turner et al. (2012) also supported a traditional, monophyletic of Velociraptorinae.[5] However, some studies found a very different group of dromaeosaurids in velociraptorinae, such as Longrich and Currie (2009), which found Deinonychus to be a non-velociraptorine, non-dromaeosaurine eudromaeosaur, and Saurornitholestes to be a member of a more basal group they named Saurornitholestinae.[8] A larger analysis in 2013 found some traditional velociraptorines, such as Tsaagan, to be more basal than Velociraptor, while others to be more closely related to Dromaeosaurus, making them dromaeosaurines. This study found Balaur, previously found to be a velociraptorine by most analyses, to be an avialan instead.[9]

The cladogram below follows a 2009 analysis by paleontologists Nicholas Longrich and Philip J. Currie, using a dataset of 114 characters scored for 23 taxa.[8]

| Eudromaeosauria |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The cladogram below follows a 2012 analysis by Turner, Makovicky and Norell, using a dataset of 474 characters scored for 111 taxa.[5]

| Eudromaeosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The cladogram below follows the phylogenetic analysys performed by Jasinski et al. 2020 during the description of Dineobellator.[10]

| Eudromaeosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- van der Lubbe, T., Richter, U. and Knotschke, N. (2009). "Velociraptorine dromaeosaurid teeth from the Kimmeridgian (Late Jurassic) of Germany." Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 54(3): 401-408.

- Naish, D. Hutt, and Martill, D.M. (2001). "Saurischian dinosaurs: theropods." in Martill, D.M. and Naish, D. (eds). Dinosaurs of the Isle of Wight. The Palaeontological Association, Field Guides to Fossils. 10, 242–309.

- Turner, A.H.; Makovicky, P.J.; Norell, M.A. (2007). "Feather quill knobs in the dinosaur Velociraptor". Science. 317 (5845): 1721. Bibcode:2007Sci...317.1721T. doi:10.1126/science.1145076. PMID 17885130.

- Currie, P.J. 1995. New information on the anatomy and relationships of Dromaeosaurus albertensis (Dinosauria: Theropoda). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 15: 576–591.

- Turner, A. H.; Makovicky, P. J.; Norell, M. A. (2012). "A Review of Dromaeosaurid Systematics and Paravian Phylogeny". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 371: 1–206. doi:10.1206/748.1. hdl:2246/6352.

- Barsbold, R. (1983). "Хищные динозавры мела Монголии" [Carnivorous dinosaurs from the Cretaceous of Mongolia] (PDF). Transactions of the Joint Soviet-Mongolian Paleontological Expedition (in Russian). 19: 89. Translated paper

- Sereno, P. C. (1998). "A rationale for phylogenetic definitions, with application to the higher-level taxonomy of Dinosauria". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen. 210 (1): 41–83. doi:10.1127/njgpa/210/1998/41.

- Longrich, N. R.; Currie, P. J. (2009). "A microraptorine (Dinosauria–Dromaeosauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of North America". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (13): 5002−5007. doi:10.1073/pnas.0811664106.

- Godefroit, Pascal; Cau, Andrea; Hu, Dong-Yu; Escuillié, François; Wu, Wenhao; Dyke, Gareth (2013). "A Jurassic avialan dinosaur from China resolves the early phylogenetic history of birds". Nature. 498 (7454): 359–362. Bibcode:2013Natur.498..359G. doi:10.1038/nature12168. PMID 23719374.

- Jasinski, S. E.; Sullivan, R. M.; Dodson, P. (2020). "New Dromaeosaurid Dinosaur (Theropoda, Dromaeosauridae) from New Mexico and Biodiversity of Dromaeosaurids at the end of the Cretaceous". Scientific Reports. 10 (1). doi:10.1038/s41598-020-61480-7. ISSN 2045-2322.

.png)

.png)