U-1-class submarine (Austria-Hungary)

The U-1 class (also called the Lake-type[1]) was a class of two submarines or U-boats built for and operated by the Austro-Hungarian Navy (German: kaiserliche und königliche Kriegsmarine). The class comprised U-1 and U-2. The boats were built to an American design at the Pola Navy Yard after domestic design proposals failed to impress the Navy. Constructed between 1907 and 1909, the class was a part of the Austro-Hungarian Navy's efforts to competitively evaluate three foreign submarine designs.

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Builders: | Pola Navy Yard, Pola |

| Operators: |

|

| Succeeded by: | U-3 class |

| Built: | 1907–1909 |

| In commission: | 1911–1918 |

| Planned: | 2 |

| Completed: | 2 |

| Scrapped: | 2 |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Type: | submarine |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: | 30.48 m (100 ft 0 in) |

| Beam: | 4.8 m (15 ft 9 in) |

| Draft: | 3.85 m (12 ft 8 in) |

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | |

| Range: | |

| Test depth: | 40 meters (131 ft 3 in) |

| Complement: | 17 |

| Armament: | 3 × 45 cm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes (two front, one rear); 5 torpedoes |

| General characteristics (after modernization) | |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: | 30.76 m (100 ft 11 in) |

| Propulsion: |

|

| Armament: |

|

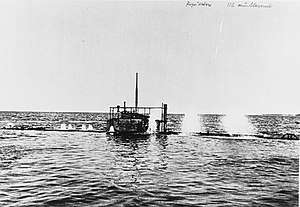

Both U-1-class submarines were launched in 1909. An experimental design, the submarines included unique features such as a diving chamber and wheels for traveling along the seabed. Extensive sea trials were conducted in 1909 and 1910 to test these features as well as other components of the boats, including the diving tanks and engines for each boat. Safety and efficiency problems related to the gasoline engines of both submarines led to the Navy to purchase new propulsion systems prior to World War I. The design of the U-1 class has been described by naval historians as a failure, being rendered obsolete by the time both submarines were commissioned into the Austro-Hungarian Navy in 1911. Despite this, tests of their design provided information that the Navy used to construct subsequent submarines. Both submarines of the U-1 class served as training boats through 1914, though they were mobilized briefly during the Balkan Wars.

At the outbreak of World War I, the U-1-class submarines were in drydock in Pola awaiting the installation of diesel engines. From 1915 to 1918, both boats conducted reconnaissance cruises out of Trieste and Pola, though neither sank any enemy vessels during the war. Declared obsolete in January 1918, both submarines were relegated to secondary duties and served as training boats at the Austro-Hungarian submarine base on Brioni Island, before being transferred back to Pola at the end of the war. When facing defeat in October 1918, the Austro-Hungarian government transferred its navy to the newly formed State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs to avoid having to hand its ships over to the Allied Powers. Following the Armistice of Villa Giusti in November 1918, the U-1-class submarines were seized by Italian forces and subsequently granted to the Kingdom of Italy under the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye in 1920. Italy scrapped the submarines at Pola later that year.

Background

With the establishment of the Austrian Naval League in September 1904 and the appointment of Vice-Admiral Rudolf Montecuccoli to the posts of Commander-in-Chief of the Navy (German: Marinekommandant) and Chief of the Naval Section of the War Ministry (German: Chef der Marinesektion) the following month,[2][3] the Austro-Hungarian Navy began an expansion program befitting a Great Power. Montecuccoli immediately pursued the efforts championed by his predecessor, Admiral Hermann von Spaun, and pushed for a greatly expanded and modernized navy.[4]

Montecuccoli's appointment as Marinekommandant coincided with the first efforts to develop submarines for Austria-Hungary. Prior to 1904, the Austro-Hungarian Navy had shown little to no interest in submarines.[5] In early 1904, after allowing the navies of other countries to pioneer submarine developments, Constructor General (German: Generalschiffbauingenieur) of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, Siegfried Popper, ordered the Naval Technical Committee (German: Marinetechnisches Kommittee, MTK) to produce a submarine design.[6] Popper himself submitted his first design for a submarine shortly before Montecuccoli took office; technical problems encountered during the initial design phase delayed further proposals from MTK for nearly a year.[7] By this time, Montecuccoli had begun to outline his plans for the future of the Austro-Hungarian Navy.[8]

Shortly after assuming command as Commander-in-Chief of the Navy, Montecuccoli drafted his first proposal for a modern Austrian fleet in early 1905. It was to consist of 12 battleships, 4 armored cruisers, 8 scout cruisers, 18 destroyers, 36 high seas torpedo craft, and 6 submarines.[8] While far more attention at the time was being placed upon the construction of battleships—particularly dreadnoughts—Montecuccoli remained interested in the development of a submarine fleet for the Austro-Hungarian Navy and encouraged further development of the program.[9]

Proposals

Following up on Montecuccoli's initial naval expansion plan, MTK submitted its specifications for a class of submarines on 17 January 1905.[5][7] The MTK design called for a single-hull boat with a waterline length of 22.1 meters (72 ft 6 in), a beam of 3.6 meters (11 ft 10 in) and a draught of 4.37 meters (14 ft 4 in). The submarines were intended to displace 134.5 metric tons (132 long tons; 148 short tons) when surfaced.[10]

The Naval Section of the War Ministry (German: Marinesektion) remained skeptical about the seaworthiness of this design. Further proposals submitted by the public as part of a design competition were all rejected by the Navy as impracticable.[6] As a result, the Navy decided to purchase designs from three different foreign firms for a class of submarines. Each design was to be accompanied by two submarines to test each boat against the others. This was done to properly evaluate the various different proposals which would come forward.[11]

Simon Lake, Germaniawerft, and John Philip Holland were each chosen by the Navy to produce a class of submarines for this competitive evaluation. The two Lake-designed submarines comprised the U-1 class, the Germaniawerft design became the U-3 class, and the Holland design became the U-5 class.[6] In 1906, the Navy formally ordered plans for the building of two boats—designated U-1 and U-2—from the Lake Torpedo Boat Company of Bridgeport, Connecticut.[12] The Austro-Hungarian Navy had contacted Lake Torpedo Boat Company as early as 1904 for a submarine design, but the decision to scrap the MTK proposal and initiate a competition among foreign builders led the Navy to formally petition a bid from the American company. In 1906, Lake traveled to Austria-Hungary to negotiate the details of the agreement and on 24 November, he signed the contracts with the Navy in Pola to construct the U-1-class submarines.[11]

Popper in particular had high praise for Lake's designs, telling the American naval architect, "When I saw your plans I recognized that you had introduced valuable features that were better than mine, and also that you had actual experience building and operating submarines, so I went to the Emperor and asked his consent to substitute your type of boat for my own...Do you know, Mr. Lake, I have been responsible for the design of all other vessels built for the Austrian Navy during the [past] 25 years?"[13]

Design

Although intended to serve as an experimental design when initially ordered, the U-1 class became the first submarines of the Austro-Hungarian Navy. The boats proved to be a disappointment. The naval historians David Dickson, Vincent O'Hara, and Richard Worth described the U-1 class as "obsolete and unreliable when completed and suffered from problems even after modifications".[14] René Greger, another naval historian, wrote that "the type proved a total failure".[1]

Despite these criticisms and shortcomings, the experimental nature of the submarines provided valuable information for the Austro-Hungarian Navy, and Lake's designs addressed what the Navy was asking for when ordering the submarine class.[15] John Poluhowich writes in his book Argonaut: The Submarine Legacy of Simon Lake that "the two submarines were completed to the satisfaction of Austrian officials".[13]

“Our company had built the first two boats for the Austrian Government, U-1 and U-2. Another type of boat had been built later which had only a fixed periscope...One day, when this submarine was running along with her periscope above the surface...some officers approached in a speedy little launch and left their cards tied to the periscope without the knowledge of the commander of the submerged vessel. This demonstrated perfectly that it is essential, both in war and peace times, for the commander of the submarine to know what is going on in his vicinity on the surface.”

— Simon Lake, The Submarine in War and Peace: Its Developments and Possibilities (1918)[16]

Their design was initially in line with Austro-Hungarian naval policy,[17][1] which stressed coastal defense and patrolling of the Adriatic Sea.[9][14] Following the onset of World War I, it became clear that Austro-Hungarian U-boats needed to be capable of offensive operations, namely raiding enemy shipping in the Adriatic and Mediterranean Seas.[14]

General characteristics

The U-1-class submarines had an overall length of 30.48 meters (100 ft 0 in), with a beam of 4.8 meters (15 ft 9 in) and a draught of 3.85 meters (12 ft 8 in) at deep load. They were designed to displace 229.7 metric tons (226 long tons; 253 short tons) surfaced, but when submerged they displaced 248.9 metric tons (245.0 long tons; 274.4 short tons).[18][19] The boats were also built with a double hull, as opposed to the single-hull design initially proposed by the MTK.[19] After their modernization, the length of the boats was increased to 30.76 meters (100 ft 11 in).[20]

Derived from an earlier concept for a submarine intended for peaceful exploring of the sea, the U-1-class design had several features typical of Lake's designs. These including a diving chamber under the bow and two variable pitch propellers. The diving chamber was intended for manned underwater missions such as destroying ships with explosives and severing off-shore telegraph cables,[18] as well as for exiting or entering the submarine during an emergency. This diving chamber proved its usefulness during the sea trials of the U-1 class when the crew of one submarine forgot to bring their lunches on-board before conducting an underwater endurance test. A diver from shore was able to transport lunch for the crew without the submarine having to resurface.[21] Lake's design also called for two retractable wheels that, in theory, could allow travel over the seabed. The design also placed the diving tanks above the waterline of the cylindrical hull, which necessitated a heavy ballast keel for vertical stability and required flooding to be done by pumps.[18][19]

The propulsion system for the U-1 class consisted of two gasoline engines for surface running and two electric motors for running submerged.[18] The gasoline engines could produce 720 bhp (540 kW), while the electric motors had an output of 200 bhp (150 kW).[19] These engines could produce a speed of 10.3 knots (19.1 km/h; 11.9 mph) while surfaced, and 6 knots (11 km/h; 6.9 mph) when submerged. The boats had an operational range of 950 nautical miles (1,760 km; 1,090 mi) while traveling at 6 knots (11 km/h; 6.9 mph) when surfaced, and 40 nmi (74 km; 46 mi) while traveling at 2 knots (3.7 km/h; 2.3 mph) when submerged.[18] For underwater steering, the design of the U-1 class featured four pairs of diving planes. These planes provided the submarines with a considerable amount of maneuverability.[19]

Both of the submarines had three 45-centimeter (17.7 in) torpedo tubes—two in the bow, one in the stern—and could carry up to five torpedoes,[18] but typically carried three.[12] While no deck guns were initially installed on the U-1 class, in 1917 a 37-millimeter (1.5 in) gun was mounted on the deck of both boats. These guns were removed in January 1918 when the boats were declared obsolete and resumed training duties.[1] The boats were designed for a crew of 17 officers and men.[18]

Boats

| Name[18] | Builder[18] | Laid down[18] | Launched[18] | Commissioned[18] | Vessels sunk or captured[18] | Tonnage sunk or captured[18] | Fate[18] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SM U-1 | Pola Navy Yard, Pola | 2 July 1907 | 10 February 1909 | 15 April 1911 | – | – | Ceded to Italy in 1920, scrapped |

| SM U-2 | 18 July 1907 | 3 April 1909 | 22 June 1911 |

Construction and commissioning

U-1 was laid down on 2 July 1907 at the Pola Navy Yard (German:Seearsenal) at Pola.[22] She was followed by U-2 on 18 July.[18][7] Construction on the boats was delayed by the need to import the American-made engines for both submarines.[21] U-1 was the first boat launched on 10 February 1908, and U-2 was launched on 3 April 1909.[18][7][lower-alpha 1]

Upon completion of the two boats, the Austro-Hungarian Navy evaluated the U-1 class in trials during 1909 and 1910. These trials were considerably longer than other sea trials due to the experimental nature of the submarines and the desire by Austro-Hungarian naval officials to test every possible aspect of the boats. While the sea trials for both submarines were under way, efforts were being made to conceal their results from the general public, and especially from the navies of foreign powers. The Austro-Hungarian government attempted to keep the construction and testing of the boats a state secret, to the point of employing many of the same measures which the Navy was using with respect to the Tegetthoff-class battleships.[9] On 13 October 1909, as the U-1-class submarines were still undergoing sea trials, Montecuccoli addressed the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Ministry about the urgent need to impose censorship restrictions on the publication of any sea trial results for Austria-Hungary's submarines. These measures were implemented and in February 1910 the level of secrecy surrounding the U-1 class was so great that a Uruguayan naval officer conducting a visit to Austria-Hungary was shown all of the Navy's warships with the explicit exception of its submarines.[23]

During these trials, extensive technical problems with the gasoline engines of both submarines were revealed. Exhaust fumes and gasoline vapor frequently poisoned the air inside the boats and increased the risk of internal explosions, and the engines were not able reach the contracted speed, which was 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) surfaced and 7 knots (13 km/h; 8.1 mph) submerged.[18][24][25] Indeed, the engine problems for both submarines were so significant that on multiple occasions their crews had to conduct emergency resurfacing to bring fresh air into the boats.[25] Because of the problems, the Austro-Hungarian Navy considered the engines to be unsuitable for wartime use and paid only for the hulls and armament of the two U-1 boats. While replacement diesel engines were ordered from the Austrian firm Maschinenfabrik Leobersdorf, they agreed to a lease of the gasoline engines at a fee of $4,544 USD annually. On 5 April 1910, U-1 suffered engine damage when her electric motors were disabled by an accidental flood.[11]

Flooding the diving tanks, which was necessary to submerge the submarines, took over 14 minutes and 37 seconds in early tests. This was later reduced to 8 minutes. At a depth of 40 meters (130 ft) the hulls began to show signs of stress and were in danger of being crushed. As a result, the commission overseeing the submarines' trials concluded that the maximum depth for the submarines should be set at 40 meters (130 ft) and that neither boat should attempt to dive deeper. The four pairs of diving planes equipped on each submarine gave the boats exceptional underwater handling, and, when the boats were properly trimmed and balanced, the boats could be held within 20 centimeters (7.9 in) of the desired depth. While surfaced, the shape of the hull of each submarine resulted in a significant bow-wave, which resulted in the bow of the boat dipping under the water. This led to the deck and bow casing of both submarines to be reconstructed in January 1915. Other tests proved the use of the submarine's underwater wheels on the seabed to be almost impossible.[26]

Ultimately, the experimental nature of the submarines resulted in a mixed set of sea trial results.[7] Despite this, the U-1-class boats outperformed the Germaniawerft-built U-3 class and the Holland-built U-5 class in both diving and steering capabilities in the Austro-Hungarian Navy evaluations.[6] After these sea trials, U-1 was commissioned on 15 April 1911; U-2 followed on 22 June.[7]

History

Pre-war

Both submarines of the U-1 class saw very limited service upon commissioning, as they were originally ordered and constructed for experimental purposes.[15] After being commissioned into the Austro-Hungarian Navy, both submarines were assigned as training boats, with each boat making as many as ten training cruises a month.[7]

Within five months of U-1's commissioning into the Austro-Hungarian Navy, the Italo-Turkish War erupted in September 1911. Despite the fact that Austria-Hungary and Italy were nominal allies under the Triple Alliance, tensions between the two nations remained throughout the war. The Austro-Hungarian Navy was placed on high alert, and the Army was deployed to the Italian border.[27] The war ultimately became localized at the request of Austria-Hungary to parts of the eastern Mediterranean and Libya, and the First Balkan War broke out before Italy and the Ottoman Empire were able to conclude a peace agreement. The Ottoman military proved insufficient to defeat its opponents and within a matter of weeks, the Balkan League of Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece, and Montenegro overran most of the Ottoman Empire's remaining European possessions.[28] By November 1912, Serbia appeared poised to obtain a port on the Adriatic Sea. Austria-Hungary strongly opposed this, as a Serbian port on the Adriatic could drastically alter the balance of power in the region by serving as a Russian naval base.[29]

Austria-Hungary found Italy in opposition to a Serbian port on the Adriatic as well. Rome opposed Serbian access to the Adriatic on the belief that Russia would use any Serbian ports to station its Black Sea fleet. Italy also feared that Austria-Hungary would one day annex Serbia, and thus gain more Adriatic coastline without any exchange of Italian-speaking territories such as Trentino or Trieste.[29] Russia and Serbia both protested to Austria-Hungary regarding its objection to a potential Serbian port on the Adriatic. By the end of November 1912, the threat of conflict between Austria-Hungary, Italy, Serbia, and Russia, coupled with allegations of Serbian mistreatment of the Austro-Hungarian consul in Prisrena led to a war scare in the Balkans. Both Russia and Austria-Hungary began mobilizing troops along their border, while Austria-Hungary began to mobilize against Serbia. During the crisis, the entire Austro-Hungarian Navy was also fully mobilized, including U-1 and U-2. They were ordered to join the rest of the fleet in the Aegean Sea in the event of a war with Serbia and Russia.[30]

By December 1912, the Austro-Hungarian Navy had, in addition to U-1 and U-2, a total of seven battleships, six cruisers, eight destroyers, 28 torpedo boats, and four submarines ready for combat.[30] The crisis eventually subsided after the signing of the Treaty of London, which granted Serbia free access to the sea through an internationally supervised railroad, while at the same time establishing an independent Albania. The Austro-Hungarian Army and Navy were subsequently demobilized on 28 May 1913.[31] After demobilization, both submarines of the U-1 class resumed their duties as training vessels. During one of these training cruises on 13 January 1914 near Fasana, U-1 was accidentally rammed by the Austro-Hungarian armored cruiser Sankt Georg. The collision destroyed the submarine's periscope.[7]

World War I

At the outbreak of World War I, U-1 and U-2 were both in drydock in Pola awaiting the installation of their new diesel engines, batteries, and periscopes.[32][21][33] To accommodate the new engines, the boats were lengthened by about 28 centimeters (11 in). These changes lowered the surface displacement to 223.0 metric tons (219 long tons; 246 short tons) but increased the submerged displacement to 277.5 metric tons (273 long tons; 306 short tons).[18] After these modernization efforts were completed, U-1 returned to training duties until 4 October 1915. Meanwhile, U-2 underwent a further refit in Pola starting on 24 January 1915. During this refit, she had a new conning tower installed, which was completed on 4 June 1915.[7]

U-1 continued as a training boat for the Austro-Hungarian Navy for just over a month, before being relocated to Trieste on 11 November to conduct reconnaissance patrols. U-2 had already been relocated to Trieste on 7 August 1915 after her new conning tower had been installed. Both boats subsequently conducted reconnaissance cruises from 1915 onward out of Trieste.[34] The relocation to Trieste was undertaken in part to dissuade Italian naval attacks or raids on the crucial Austro-Hungarian city. The U-1-class submarines were already outdated by 1915, but their relocation to Trieste helped to dissuade the Italians from their plans to bombard the port, as Italian military intelligence suggested the submarines were on regular patrol in the waters off Trieste.[35]

After being stationed out of Trieste for just over two years, U-1 was sent back to Pola on 22 December 1917, while U-2 remained at Trieste until the end of the year. Despite being declared obsolete on 11 January 1918, both submarines remained in service as training boats at the submarine base at Brioni Island.[7] In mid-1918, the U-1-class submarines were considered for service as minesweepers, as the diving chamber in the boats could allow divers to sever the anchoring cables of sea mines. The poor condition of the boats prevented the plan from being implemented.[36] Near the war's end, both boats were once more taken to Pola.[34] By October 1918 it had become clear that Austria-Hungary was facing defeat. With various attempts to quell nationalist sentiments failing, Emperor Karl I decided to sever Austria-Hungary's alliance with Germany and appeal to the Allied Powers in an attempt to preserve the empire from complete collapse. On 26 October, Austria-Hungary informed Germany that their alliance was over. In Pola, the Austro-Hungarian Navy was in the process of tearing itself apart along ethnic and nationalist lines.[37]

On 29 October the National Council in Zagreb announced Croatia's dynastic ties to Hungary had come to a formal conclusion. The National Council also called for Croatia and Dalmatia to be unified, with Slovene and Bosnian organizations pledging their loyalty to the newly formed government. This new provisional government, while throwing off Hungarian rule, had not yet declared independence from Austria-Hungary. Thus Emperor Karl I's government in Vienna asked the newly formed State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs for help maintaining the fleet stationed at Pola and keeping order among the navy. The National Council refused to assist unless the Austro-Hungarian Navy was first placed under its command.[38] Emperor Karl I, still attempting to save the Empire from collapse, agreed to the transfer, provided that the other "nations" which made up Austria-Hungary could claim their fair share of the value of the fleet at a later time.[39] All sailors not of Slovene, Croatian, Bosnian, or Serbian background were placed on leave for the time being; the officers were given the choice of joining the new navy or retiring.[39][40]

The Austro-Hungarian government thus decided to hand over the bulk of its fleet to the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs without a shot being fired. This was considered preferential to handing the fleet to the Allies, as the new state had declared its neutrality. Furthermore, the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs had also not yet publicly rejected Emperor Karl I, keeping the possibility of reforming the Empire into a triple monarchy alive. The transfer to the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs began on the morning of 31 October, with Rear Admiral (German: Konteradmiral) Miklós Horthy meeting representatives from the South Slav nationalities aboard his flagship, Viribus Unitis. After "short and cool" negotiations, the arrangements were settled and the handover was completed that afternoon. The Austro-Hungarian Naval Ensign was struck from Viribus Unitis, and was followed by the remaining ships in the harbor.[41] Control over the ships in the harbor, and the head of the newly-established navy for the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs, fell to Captain Janko Vuković, who was raised to the rank of admiral and took over Horthy's old responsibilities as Commander-in-Chief of the Fleet.[42][40]

Post-war

Under the terms of the Armistice of Villa Giusti, signed between Italy and Austria-Hungary on 3 November 1918, this transfer was not recognized. Italian ships thus sailed into the ports of Trieste, Pola, and Fiume the following day. On 5 November, Italian troops occupied the naval installations at Pola.[43] The State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs attempted to hold onto their ships, but lacked the men and officers to do so as most sailors who were not South Slavs had already gone home. The National Council did not order any men to resist the Italians, but they condemned Italy's actions as illegitimate. On 9 November, all remaining ships in Pola had the Italian flag raised. At a conference at Corfu, the Allied Powers agreed the transfer of Austria-Hungary's navy to the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs could not be accepted, despite sympathy from the United Kingdom.[44] Faced with the prospect of being given an ultimatum to hand over the former Austro-Hungarian warships, the National Council agreed to hand over the ships beginning on 10 November 1918.[45]

In 1920 the final distribution of the ships was settled among the Allied powers under the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye.[46] Both submarines of the U-1 class were ceded to Italy as war reparations and scrapped at Pola in the same year.[18] Due to the training and reconnaissance missions the submarines engaged in throughout the war, neither boat sank any ships during their careers.[47]

Notes

Footnotes

- In their book The German Submarine War, 1914–1918, R. H. Gibson and Maurice Prendergast report that U-1 was launched in 1911 and U-2 in 1910 (p. 383).

Citations

- Greger 1976, p. 68.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 170.

- Vego 1996, p. 38.

- Vego 1996, pp. 38–39.

- Novak 2011, p. 9.

- Gardiner 1985, p. 340.

- Sieche 1980, p. 18.

- Vego 1996, p. 39.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 199.

- Sieche 1980, pp. 16–17.

- Sieche 1980, p. 16.

- Gibson & Prendergast 2003, p. 383.

- Poluhowich 1999, p. 99.

- Dickson, O'Hara & Worth 2013, p. 27.

- Sieche 1980, pp. 17–18.

- Lake 1918, p. 48.

- Sokol 1968, p. 37.

- Gardiner 1985, p. 342.

- Sieche 1980, p. 17.

- Novak 2011, p. 135.

- Novak 2011, p. 10.

- Sieche, Erwin. "The Austro-Hungarian Submarine Force". The Great War Primary Documents Archive. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- Sondhaus 1994, pp. 199–200.

- Mitchell 1908, p. 858.

- Novak 2011, p. 16.

- Sieche 1980, pp. 16–18.

- Vego 1996, pp. 87–88.

- Vego 1996, pp. 134–136.

- Vego 1996, p. 139.

- Vego 1996, p. 140.

- Vego 1996, pp. 144–145, 153.

- Gardiner 1985, p. 341.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 258.

- Gibson & Prendergast 2003, p. 388.

- Novak 2011, p. 67.

- Novak 2011, p. 123.

- Sondhaus 1994, pp. 350–351.

- Sondhaus 1994, pp. 351–352.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 352.

- Sokol 1968, pp. 136–137, 139.

- Koburger 2001, p. 118.

- Sondhaus 1994, pp. 353–354.

- Sieche 1985, p. 137.

- Sieche 1985, pp. 138–140.

- Sondhaus 1994, pp. 357–359.

- Sondhaus 1994, p. 359.

- Novak 2011, pp. 137–138.

References

- Dickson, W. David; O'Hara, Vincent; Worth, Richard (2013). To Crown the Waves: The Great Navies of the First World War. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-61251-082-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1906–1921. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8. OCLC 12119866.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gibson, R. H.; Prendergast, Maurice (2003) [1931]. The German Submarine War, 1914–1918. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-314-7. OCLC 52924732.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Greger, René (1976). Austro-Hungarian Warships of World War I. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-7110-0623-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Koburger, Charles W. (2001). The Central Powers in the Adriatic, 1914–1918: War in a Narrow Sea. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-97071-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lake, Simon (1918). The Submarine in War and Peace: Its Developments and Possibilities. Philadelphia, PA: J. B. Lippincott Company. OCLC 656930559.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mitchell, W. (1908). "Naval Notes". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. LII (359). OCLC 8007941.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Novak, Jiri (2011). Austro-Hungarian Submarines in World War I. Sandomierz: Mushroom Model. ISBN 978-83-61421-44-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Poluhowich, John J. (1999). Argonaut: The Submarine Legacy of Simon Lake. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-0-89096-894-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sieche, Erwin F. (1980). "Austro-Hungarian Submarines". Warship. 2. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-976-4. OCLC 233144055.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sieche, Erwin F. (1985). "Zeittafel der Vorgange rund um die Auflosung und Ubergabe der k.u.k. Kriegsmarine 1918–1923" [Timeline of the Process Surrounding the Dissolution and Surrender of the k.u.k. [imperial and Royal] Navy]. Marine—Gestern, Heute (in German). 12 (1): 129–141. OCLC 648103394.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sokol, Anthony (1968). The Imperial and Royal Austro-Hungarian Navy. Annapolis, MD: United States Naval Institute. OCLC 462208412.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (1994). The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918: Navalism, Industrial Development, and the Politics of Dualism. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-034-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vego, Milan N. (1996). Austro-Hungarian Naval Policy: 1904–14. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7146-4209-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

External links

- Helgason, Guðmundur. "WWI U-boats: U K.u.K. U1". U-Boat War in World War I. uboat.net. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- Helgason, Guðmundur. "WWI U-boats: U K.u.K. U2". U-Boat War in World War I. uboat.net. Retrieved 28 July 2018.