Tumba francesa

Tumba francesa is a secular Afro-Cuban genre of dance, song, and drumming that emerged in Oriente, Cuba. It was introduced by slaves from the French colony of Saint-Domingue (which would later become the nation of Haiti) whose owners resettled in Cuba's eastern regions following the slave rebellion during the 1790s. The genre flourished in the late 19th century with the establishment of sociedades de tumba francesa (tumba francesa societies), of which only three survive.

| Tumba francesa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Stylistic origins | 18th century Afro-Haitian music |

| Cultural origins | Early 19th century in Oriente, Cuba |

| Typical instruments | Catá, premier, bulá, segón, tambora, chachá or maruga |

| Regional scenes | |

| Santiago de Cuba, Guantánamo | |

Characteristics

Tumba francesa combines musical traditions of West African, Bantu, French and Spanish origin. Cuban ethnomusicologists agree that the word "tumba" derives from the Bantu and Mandinka words for drum.[1][2] In Cuba, the word tumba is used to denote the drums, the ensembles and the performance itself in tumba francesa.[3]

Instrumentation

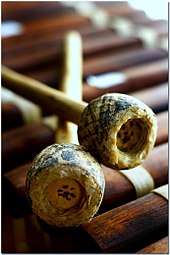

Tumbas francesas are directed by a mistress of ceremonies called mayora de plaza. Performances generally begin with improvised solo singing in a mixture of Spanish and French patois termed kreyol cubano or patuá cubano by the lead vocalist (composé).[4] After the introduction, the catá (a wooden cylindrical idiophone struck with two sticks) is played, and the composé alternates call and response singing with a group of female vocalists (tumberas).[3] After the catá establishes the beat, the three tumbas are played. The tumbas are single-headed hand drums; from largest to smallest they are called premier (or manma), bulá and segón. The premier is now commonly called quinto, as it fulfills the same lead, improvisatory role as the quinto does among the conga drums in Cuban rumba.[3] In the toque masón, a double-headed bass drum called tamborita (or simply tambora) establishes the rhythm together with the catá. In addition, a shaker called chachá or maruga is commonly played by the tumberas and the mayora throughout the performance.[3] The structure of tumba francesa is related to an eastern type of Cuban rumba called tahona.[5]

Toques

There are three main toques, or types of tumba performance, each associated with a specific dance.

- Masón. This is the first toque. It features the whole music ensemble and is associated with a quadrille-style dance similar to the contradanza.

- Yubá. This toque follows the masón and involves the catá and the three tumbas. It is accompanied by the main tumba dance, which is improvised. There are two subtypes of yubá: macota and cobrero.[3]

- Frenté (or fronté). Originally the final section of the yubá, this is now considered an individual toque. It involves the catá, the premier and the bulá.[3] It is played in front of the drums, hence the name.

An additional toque called cinta is only performed in Santiago de Cuba. It is called so because the performance takes place around a tree trunk with coloured bands (cintas), which are red, white and blue.

Dance

The dance in tumba francesa is similar to Haitian affranchi, which involves a series of straight-backed, held-torso, French style figures followed by African improvisation on the final set,[6] but tumba francesa is danced to drums instead of string and woodwind instruments.[7] The clothes of the dancers are colorful and flamboyant.[8]

History

Tumbas francesas can be traced back to the late 18th century when the Haitian Revolution triggered the migration of French colonists from Saint-Domingue, bringing their slaves to the Oriente Province of Cuba. By the late 19th century, following the abolition of slavery in 1886, tumba francesa societies became established in this region, especially in Santiago de Cuba and Guantánamo. Their establishment was in many ways similar to the old African cabildos.[3] Performers identify tumba francesa as French-Haitian, acknowledging it as a product of Haiti which now resides in Cuba.[7] By the second half of the 20th century, tumbas francesas were still performed in eastern Cuba, especially the toque masón. Other toques however are only played in the context cultural associations. Three tumba francesa societies survive at the moment: La Caridad de Oriente (originally La Fayette) in Santiago de Cuba; Bejuco in Sagua de Tánamo, Holguín; and Santa Catalina de Riccis (originally La Pompadour) in Guantánamo.[3]

Recordings

Unlike other Afro-Cuban genres, tumba francesa remains poorly documented in terms of recordings. The 1976 LP Antología de la música afrocubana VII, produced by Danilo Orozco and released by Areito, presents a variety of yubá and masón toques.[9]

See also

References

- Ortiz, Fernando (1954). Los instrumentos de la música afrocubana, Vol. IV. Havana, Cuba: Cárdenas y cía. p. 114.

- Alén, Olavo (1986). La música en las sociedades de tumba francesa. Havana, Cuba: Casa de las Américas. p. 45.

- Ramos Venereo, Zobeyda (2007). "Haitian Traditions in Cuba". In Kuss, Malena (ed.). Music in Latin America and the Caribbean: An Encyclopedic History, Vol. 2. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. pp. 265–280.

- Figueroa Arencibia, Vicente Jesús; Ourdy, Pierre Jean (2004). "Contacto lingüístico español-kreyol en una comunidad cubano-haitiana de Santiago de Cuba". Revista Internacional de Lingüística Iberoamericana. 2 (2): 41–55. JSTOR 41678051.

- Orovio, Helio (2004). Cuban Music from A to Z. Bath, UK: Tumi. p. 208.

- Caribbean and Atlantic Diaspora Dance: Igniting Citizenship. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- Daniel, Yvonne. Dancing Wisdom: Embodied Knowledge in Haitian Vodou, Cuban Yoruba, and Bahian Candombié. p. 122. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- "La Tumba Francesa". UNESCO.org. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- Alén, Olavo (1976). Liner notes of Antología de la música afrocubana VII. Havana, Cuba: Areito.

Further reading

- Estéban Pichardo y Tapia (1836). "Tumba". Diccionario provincial de voces cubanas (in Spanish). Matanzas: Imprenta de la Real Marina – via Internet Archive.