Maloya

Maloya is one of the two major music genres of Réunion, usually sung in Réunion Creole, and traditionally accompanied by percussion and a musical bow.[1] Maloya is a new form that has origins in the music of African and Malagasy slaves and Indian indentured workers on the island, as has the other folk music of Réunion, séga. World music journalists and non-specialist scholars sometimes compare maloya to the American music, the blues, though they have little in common.[2] Unlike the blues, maloya was considered such a threat to the French state that in the 1970s it was banned.[3]

| Maloya | |

|---|---|

| Typical instruments | Vocals, percussion, musical bow |

| Regional scenes | |

| Réunion | |

It is sometimes considered the Reunionese version of séga.

Description

Compared to séga, which employs numerous string and wind European instruments, traditional maloya uses only percussion and the musical bow. Maloya songs employ a call-response structure.[4]

Instruments

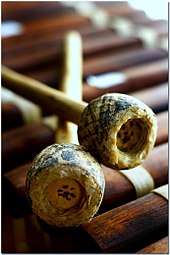

Traditional instruments include:

- roulér - a low-tuned barrel drum played with the hands

- kayamb - a flat rattle made from sugar cane tubes and seeds

- pikér - a bamboo idiophone played with sticks

- sati - a flat metal idiophone played with sticks

- bob - a braced, struck musical bow

Origins

The indigenous music and dance form of maloya was often presented as a style of purely African origin, linked ancestral rituals from Africa ("service Kaf" and Madagascar (the "servis kabaré"), and as such a musical inheritance of the early slave population of the island. More recently, however, the possible influence of the sacred drumming of the Tamil religious rituals has been introduced by Danyèl Waro, which makes Maloya' heterogeneous African Malagasy and Indian influences more explicit.[7]

History

Maloya was banned until the sixties because of its strong association with creole culture.[2] Performances by some maloya groups were banned until the eighties, partly because of their autonomist beliefs and association with the Communist Party of Réunion[5]

Nowadays, one of the most famous maloya musicians is Danyèl Waro. His mentor, Firmin Viry, is credited as having rescued maloya from extinction.[2] According to Françoise Vergès, the first public performance of maloya was by Firmin Viry in 1959 at the founding of the Communist Party[8] Maloya was adopted as a medium for political and social protest by Creole poets such as Waro, and later by groups such as Ziskakan.[1] Since the start of the 1980s, maloya groups, such as Ziskakan, Baster, Firmin Viry, Granmoun Baba, Rwa Kaff and Ti Fock, some mixing maloya with other genres such as séga, zouk, reggae, samba, afrobeat, jazz and rock, have had recognition outside the island.[9]

Cultural significance

Maloya was inscribed in 2009 on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity of UNESCO for France.[10]

This musical form was the subject of a 1994 documentary film by Jean Paul Roig, entitled Maloya Dousman.[11]

See also

- Sega music, the other traditional music of Réunion

- Music of Réunion

- List of Réunionnais

- List of blues genres#Blues-like genres

References

- Alex Hughes; Keith Reader (2001). Encyclopedia of contemporary French culture. Taylor & Francis. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-415-26354-2. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

- Nidel, Richard (2005). World music: the basics. Routledge. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-415-96800-3. Retrieved 2009-07-31.

maloya music.

- Denselow, Robin (5 October 2013). "Maloya: The protest music banned as a threat to France". BBC News. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- Hawkins, Peter (2007). The other hybrid archipelago: introduction to the literatures and cultures of the francophone Indian Ocean. Lexington Books. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-7391-1676-0. Retrieved 2009-07-31.

- James Porter; Timothy Rice; Chris Goertzen (1999). The Garland encyclopedia of world music. Indiana University: Taylor & Francis. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-8240-4946-1. Retrieved 2009-07-31.

- Tom Masters; Jan Dodd; Jean-Bernard Carillet (2007). Mauritius, Réunion & Seychelles. Lonely Planet. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-74104-727-1. Retrieved 2009-07-31.

origin sega music.

- Hawkins, Peter (2003). "How Appropriate is the Term "Post-colonial" to the Cultural Production of Reunion?". In Salhi, Kamal (ed.). Francophone Post-Colonial Cultures: Critical Essays. Lexington Books. pp. 311–320. ISBN 978-0-7391-0568-9.

- Francoise Verges, Monsters and Revolutionaries, pp.309–10, n.3

- Frank Tenaille (2002). Music is the weapon of the future: fifty years of African popular music. Chicago Review Press. p. 92. ISBN 1-55652-450-1.

- "Intangible Heritage Home - intangible heritage - Culture Sector - UNESCO". www.unesco.org. Retrieved 2018-09-17.

- "Maloya Dousman". Festival listing. African Film Festival of Cordoba. Retrieved 12 March 2012.